Laryngo-onycho-cutaneous (LOC) syndrome was reclassified as a subtype of junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB) based on clinical features similar to JEB and its association, in the majority of patients from the Punjab, with a unique mutation affecting the N terminus of the α3 chain of LM332. Although LOC syndrome is now a subtype of JEB(JEB-LOC) JEB-LOC has a distinct clinicopathologic appearance and molecular fingerprint. The intricacies of the JEB-LOC subtype are discussed in this article with regard to disease presentation, pathogenesis, management, and prognosis.

Our understanding of the pathogenesis of laryngo-onycho-cutaneous (LOC) syndrome, now classified as a subtype of junctional epidermolysis bullosa, other (JEB-O), has come a long way since the earliest documented case by Shabbir in 1986. In a concerted effort to elucidate the disease origin and chain of events leading to LOC syndrome (previously termed, laryngeal and ocular granulation tissue in children from the Indian subcontinent [LOGIC] syndrome and Shabbir disease), more than a dozen articles have been published. LOC syndrome was appropriately reclassified as a subtype of JEB based on its clinical features being similar to JEB and its association, in the majority of patients from the Punjab, with a unique mutation affecting the N terminus of the α3 chain of LM332. Although LOC syndrome is now a subtype of JEB-O, aptly termed JEB-LOC, it is important to acknowledge JEB-LOC has a distinct clinicopathologic appearance and molecular fingerprint. Therefore, the intricacies of the JEB-LOC subtype are discussed in this article with regard to disease presentation, pathogenesis, management, and prognosis.

Disease presentation

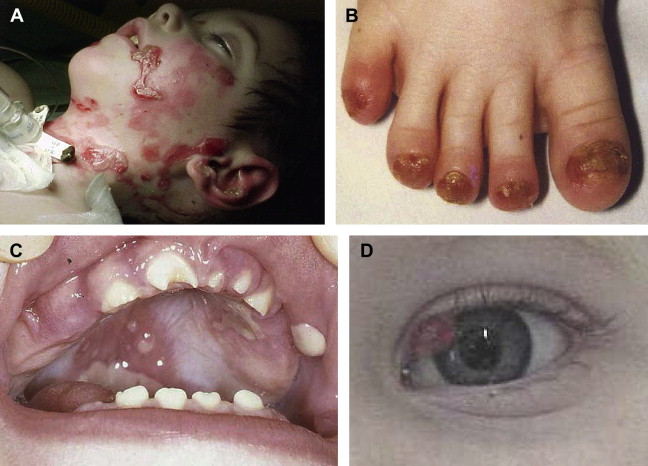

Described mainly in the offspring of consanguineous Muslim families originating in the Punjabi region of Pakistan and India, JEB-LOC is rare and has an autosomal recessive inheritance. Few JEB-LOC cases have been reported in the absence of consanguineous coupling. It is characterized by an altered cry at birth, erosions, nail abnormalities, and aberrant production of granulation tissue, resulting in conjunctival and laryngeal granulomatous papules. Patients are diagnosed in the first few months of infancy and the disease progresses with multiple cutaneous manifestations. JEB-LOC patients acquire facial erosions originating from short-lived blistering, conjunctival papules, and teeth deformities (ie, notched teeth) ( Fig. 1 ). In contrast to the excessive erosions and bulla formation described in other JEB subtypes, patients with JEB-LOC have minimal blistering and extensive granulation formation. The conjunctival lesions start in the lateral portion of the eye and result in symblepharon. The conjunctival granulation tissue often leads to total palpebral occlusion and blindness. Conjunctival granulation tissue is rare outside this variant.

Disease pathogenesis

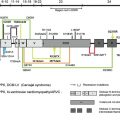

The biology of the two laminin A3 isoforms is reviewed in detail in the article by Hamill and colleagues elsewhere in this issue. In most JEB-LOC cases, in patients of Punjabi origin, there is a homozygous recessive mutation in LAMA3A , leading to the foreshortening of a critical portion of the N terminus of the α3 chain laminin-5 trimer ( Fig. 2 ). Studies suggest that extracellular matrix homeostasis is altered when the basal keratinocytes secrete the abbreviated α3 chain. This aberrant microenvironment provides a venue for erosion along the mucosal membranes, including the nail bed, and throughout the larynx. The tissue localization of the laminin α3A corresponds to the clinical manifestations of JEB-LOC: with LM332 this applies to the skin, nail, and mucous membrane fragility, but with LM311 (another laminin containing the α3A variant, which is present in the lungs) the JEB-LOC patients also are susceptible to pneumonia. The conjunctival involvement is another striking feature of the JEB-LOC variant. Expression studies of the relative amounts of LAMA3A versus LAMA3B might assist in explaining this, as one study of the conjunctiva in LOC syndrome found the granulating cells to be mainly fibroblastic in origin and to have reduced p63 expression. Missense mutations in the tumor suppressor gene encoding p63 lead to ankyloblepharon in Hay-Wells (ankyloblepharon–ectodermal dysplasia–clefting) syndrome, so reduced p63 in LOC syndrome might be related to the limbal margin granulation overgrowth in JEB-LOC.

Similar to other junctional subtypes of EB, immunofluorescence mapping exhibits avidity to type IV collagen below the blister and BP180 above the blister in patients with the JEB-LOC variant. JEB-LOC diverges molecularly from other JEB subtypes, however, in that laminin α3, β3, and γ2 antibody studies may have normal luminous intensity compared with control tissues.

The first non-Punjabi case was a white boy with nonconsanguineous parents of Irish descent, who had overlapping clinical features of JEB and JEB-LOC ( Table 1 ), with the conjunctival papules. He had a paternal LAMA3 splice mutation, which would have affected the C terminus, which is common to the LAMA3A and LAMA3B variants, and a maternal exon 39 I17N missense mutation, affecting only the LAMA3A variant, with consequent JEB-LOC features. The isoleucine is highly conserved in evolution, suggesting it has an important function in the protein. It changes from hydrophobic to hydrophilic (asparagine), which is likely to affect the protein’s conformation and interactions. This overlap case provided the first proof that JEB-LOC was a variant of JEB after much earlier speculation.

| Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa | Laryngo-onycho-cutaneous Syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Erosions | +++ | + |

| Granulation tissue | ++ | ++ |

| Nail dystrophy | +++ | +++ |

| Conjunctival eye lesions | ± | +++ |

| Laryngeal involvement | +++ | +++ |

| Enamel defects | +++ | ++ |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree