Lamellar High SMAS Face-Lift

Dino Elyassnia

Timothy Marten

DEFINITION

As face-lift techniques have evolved, it has become clear that an attractive and natural appearance is not possible without diverting tension away from the skin to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) and platysma.

Using the skin as the vehicle to support sagging tissue will always result in poor scars, tragal retraction, earlobe malposition, and a tight unnatural look.

The SMAS, however, is capable of providing sustained support to facial tissues while allowing only redundant skin to be excised and wound closure under no tension. This averts a tight, “pulled” appearance and produces high-quality scars.

A SMAS flap is a reliable and time-tested method of treating the SMAS and has been shown to provide excellent longterm outcomes. A flap is likely less destructive to the SMAS compared to various plication techniques and can be easily raised in secondary and tertiary procedures when carried out skillfully.

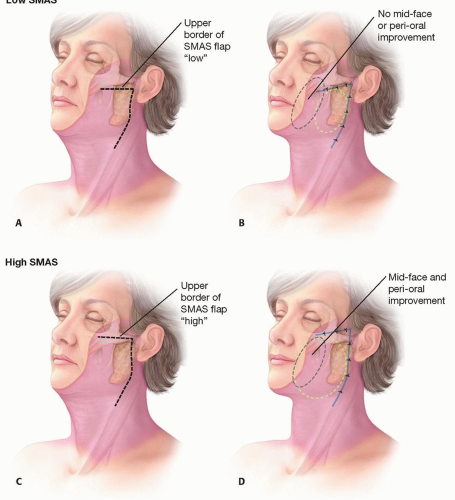

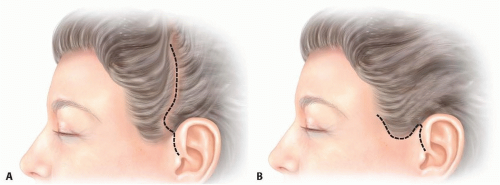

The conventional “low” cheek SMAS flap elevated below the zygomatic arch suffers from the drawback that it cannot, by design, have an impact on tissues of the midface and infraorbital region. Planning the flap “higher” along the superior border of the zygomatic arch provides the biomechanical means by which a combined and simultaneous lift of the midface, lower cheek, and jowl can be obtained and avoids the need to perform a separate mid-face-lift (FIG 1).

ANATOMY

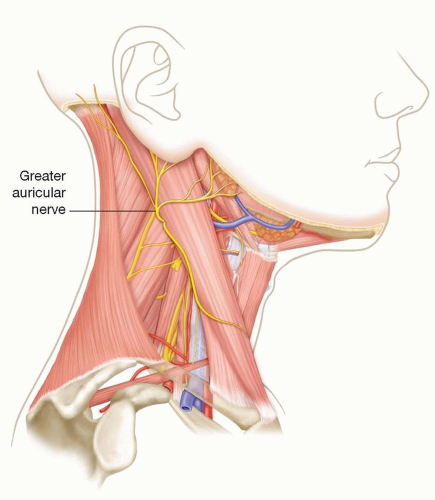

The great auricular nerve is a sensory nerve derived from the cervical plexus and provides sensation to the earlobe and lateral cheek (FIG 2). It runs obliquely from the posterior belly of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the earlobe. The classic external landmark to locate the nerve is at the midbelly of the sternocleidomastoid muscle 6.5 cm inferior to bony external auditory canal.1 The most common area of injury is where the nerve emerges from around the posterior border of sternocleidomastoid muscle.

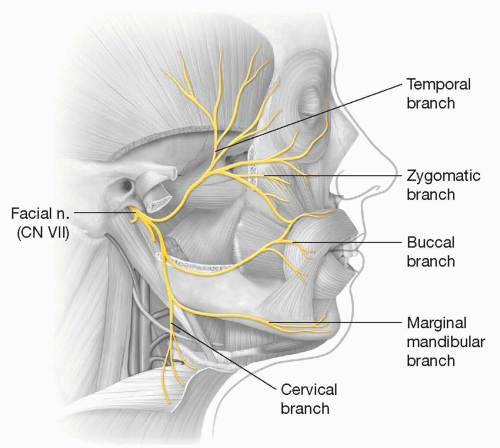

The facial nerve emerges through the stylomastoid foramen and is immediately protected by the parotid gland. Within the parotid, it divides into an upper and lower trunk and then into its five major branches: the frontal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical (FIG 3). The branches leave the parotid gland lying on the surface of the masseter immediately deep to the parotidomasseteric fascia. Medial to the masseter, the nerve branches lie on the buccal fat pad and at the same depth as the parotid duct and facial vessels. The nerve branches then proceed to innervate the mimetic muscles on their deep surface (except for the deep layer of muscles, mentalis, levator anguli oris, and buccinator).

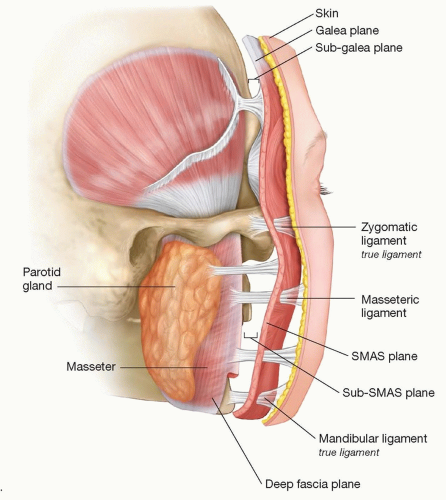

The retaining ligaments of the face (FIG 4) are vertically oriented fibers that penetrate the concentric horizontal layers of the face and function in a supportive role.2,3 There seems to be two types of retaining ligaments:

The first type is true osteocutaneous ligaments that run from the periosteum to the dermis and are made up of the zygomatic and mandibular ligaments.

The second type of retaining ligaments is formed by a coalescence of superficial and deep facial fascia that form fibrous connections vertically spanning from deep structures such as the parotid gland and masseter muscle to the overlying dermis. Examples of these include parotid and masseteric cutaneous ligaments.

The parotid cutaneous ligaments span over the entire surface of the parotid gland.

The masseteric cutaneous ligaments are a series of fibrous bands that are found along the entire anterior border of the masseter muscle starting in the malar region down to the mandibular border.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A focused history should include all previous cosmetic surgery or treatments including previous face-lifts, injectables, or laser treatments.

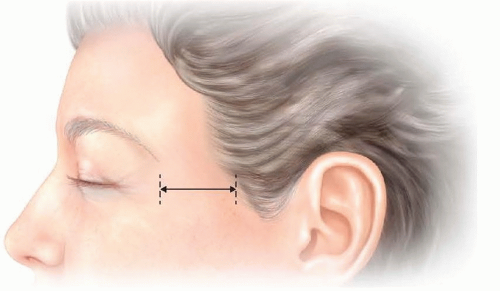

To determine the proper location for the temporal portion of the face-lift incision, each patient’s cheek skin redundancy must be examined, and location of temple and sideburn hair noted. Assessing cheek skin redundancy requires pinching up redundant skin over the upper cheek and measuring it. Also, the distance between the lateral orbit and anterior aspect of the temporal hairline must be measured. In youthful individuals, the distance should measure no more than 4 to 5 cm (FIG 5).

If cheek skin redundancy is small and ample temple and sideburn hair is present, a temple incision can be placed within the temple scalp (FIG 6A).

When the temporal hairline is predicted to shift more than 5 cm away from the lateral orbit or sideburn shifted above the junction of the ear with the scalp, a temple hairline incision should be used (FIG 6B). Failure to follow this plan can result in unnatural shifting or displacement of the temporal hair.

Like the temple, planning the appropriate location for the occipital incision requires examining each patient’s neck skin redundancy. This is done like the cheek and entails pinching up tissue over the upper lateral neck and measuring it.

If 2 cm or less of excess neck skin is present, the incision can be placed transversely, high on the occipital scalp into the hair.

If more than 2 cm of neck skin redundancy is present, the incision should be placed along the occipital hairline but then turned into the scalp at the junction of the thick and thin hair at the nape of the neck (FIG 7). Failure to follow this plan can result in a visible notching of the occipital hairline.

IMAGING

Typically, radiographs are not necessary in facial rejuvenation surgery.

All patients should have standardized photographs taken preoperatively, and any markings made preoperatively on patients should be photographed as well.

These photos should be used intraoperatively to help guide treatment.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

A lamellar dissection for a high SMAS face-lift involves elevating the skin and SMAS as separate layers so that they can be advanced “bidirectionally” along different vectors and suspended under differential tension. Because skin and SMAS age at different rates and along somewhat different vectors, a lamellar strategy is needed to address each layer individually and to create a natural improvement.4,5

On the other hand, if a composite dissection is performed, the skin and SMAS must be advanced with the same amount in the same direction under more or less similar tension, which can result in skin overshifting, skin overtightening, and other unnatural appearances.

Preoperative Planning

All patients undergo a preoperative physical evaluation, and patients with significant medical problems must be cleared by their internist.

FIG 2 • The great auricular nerve can be seen lying over the midbelly of the sternocleidomastoid muscle 6.5 cm below the external auditory canal.

Patients are required to avoid all medications or supplements that increase the risk of bleeding for 2 weeks prior to surgery.

All patients who smoke are asked to quit 4 weeks before their procedure and are required to avoid smoking and all secondhand smoke for 2 weeks after. Patients who smoke or have a significant history of smoking are advised in writing that their risk of serious complications is significantly higher than is that of nonsmokers.

Patients are instructed no to color, “perm,” or otherwise chemically treat their hair for 2 weeks before surgery and after surgery as this can result in hair breakage and hair loss.

It is important that adequate OR time be allotted for contemporary face-lift procedures. A high SMAS face-lift, when performed in conjunction with foreheadplasty, eyelid surgery, fat injections, or other facial procedures, will often take up to 6 to 8 hours or more. It is strongly recommended that any surgeon new to these techniques consider staging a full-face rejuvenation over 2 separate days. Typically, face-lift and neck lift are performed the first day, and the patient is then kept overnight and then returned to the OR the following day or a few days later for the remainder of the procedures.

Positioning

The majority of our face-lifts are performed under deep sedation administered by an anesthesiologist using a laryngeal mask airway (LMA).

The patient is placed supine on a warmed and well-padded operating table with special effort made to ensure that all pressure points are well protected.

The patient’s lower extremities are then elevated and antiembolic pedal compression devices applied.

Each patient receives a full surgical scrub of the entire scalp, face, ears, nose, neck, shoulders, and upper chest with fullstrength (1:750) benzalkonium chloride (Zephran) solution. The head is then placed through the opening of a “split sheet” leaving the entire head and neck region including the scalp unobstructed from the clavicles up.

The breathing circuit is draped separately from the patient by wrapping it with a sterile sheet that allows it to move during the procedure as the patient’s head is turned from side to side.

After the general prep and draping, the surface of the ear is prepped with Betadine using cotton swabs, and then Kittner “peanut” sponges are placed in each auditory meatus.

Approach

0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine 1:200 000 is used for sensory nerve blocks and for infiltrating the area marked for incision. Areas of subcutaneous dissection are infiltrated with 0.1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:1 000 000.

All incisions on the scalp or along scalp-skin interfaces must be made precisely parallel to hair follicles to avoid injury to them that can result in peri-incisional alopecia.

The prehelical portion of the preauricular incision should be made as a soft curve paralleling the curve of the anterior border of the helix. As the tragus is approached, the incision is carried into the depression superior to it.

Next, the incision is carried precisely along the posterior margin of the tragus in a retrotragal position. This location provides for the best option for avoiding a color or texture mismatch in the preauricular skin and the best concealment of the scar.

At the inferior portion of the tragus, the incision must turn anteriorly and then again inferiorly into the crease between the anterior lobule and cheek. This creates a distinct inferior tragal border.

The incision will then continue around the lobule and then precisely within the auriculomastoid crease. The occipital and temple portions of the incision are made according to the preoperative plan (see above).

TECHNIQUES

▪ Skin Flap Elevation

Cheek flap dissection is begun using Adson forceps and a small Kaye scissors or scalpel grasping only tissue edges that will later be excised. Once the edge is elevated, gentle traction is applied by the assistant with doublepronged skin hooks.

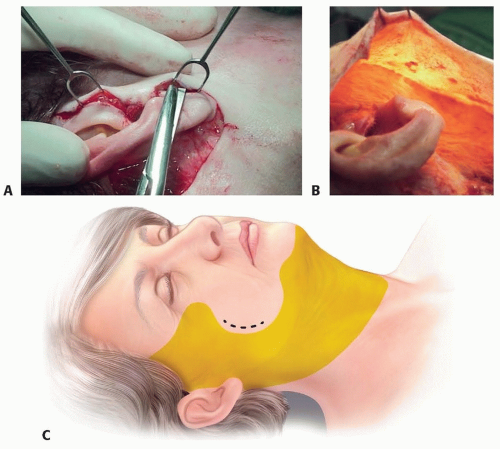

Dissection is then carried out using medium Metzenbaum scissors with the surgeon and assistant working together using a “four-handed” technique (TECH FIG 1A):

The assistant applies gentle skin traction upon the skin flap directed toward the surgeon with one doublepronged skin hook in each hand, while the surgeon dissects and provides gentle countertraction toward the assistant with the fingertips of the nondominant hand.

As the dissection advances, one skin hook is exchanged for a small Deavor malleable-type retractor, and the remaining skin hook is used to drape the flap over the retractor.

TECH FIG 1 • “Four-handed” technique. A. The assistant applies gentle traction upon the skin flap toward the surgeon with two large double-pronged skin hooks with one retractor held in each hand. The surgeon then dissects while providing gentle countertraction toward the assistant with the fingertips of the opposite hand. B. Appearance of a transilluminated skin flap in the cheek. If dissection is in the proper plane as in this case, the undersurface of the flap will have a rough, “cobblestone” appearance to the fat. C. Extent of subcutaneous undermining. Shaded area shows area of subcutaneous undermining. Note that the platysma-cutaneous ligaments (black dots) are not undermined and are preserved. Preservation of platysma-cutaneous ligaments and proper elevation and fixation of the SMAS will provide support of lateral perioral tissues.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access