Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars

Yoon-Soo Cindy Bae-Harboe

I. BACKGROUND

Keloids and hypertrophic scars (HSs) represent an excessive and aberrant healing response to cutaneous injuries, such as acne, trauma, surgery, and piercing. Both are seen in all races, especially in individuals with dark skin. Common anatomic sites for both HSs and keloids include the earlobes, chest, lower legs, and upper back. In general, HSs remain in the area and shape of original injury, whereas keloids expand beyond the site of initial trauma and can be recalcitrant to treatment.

The pathogenesis of HSs and keloids is unclear. Fibroblasts from HSs and keloids demonstrate excessive proliferative and low apoptosis properties. In addition to the increasing production of collagen, fibroblasts from HSs and keloids also produce an increased amount of elastin, fibronectin, and hyaluronic acid. Tumor growth factor-β (TGF-β) appears to play a central role in the pathogenesis as evidence indicates that TGF-β isoforms 1 and 2 are particularly involved in collagen synthesis promotion and scarring, while isoform 3 is involved in scar prevention.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

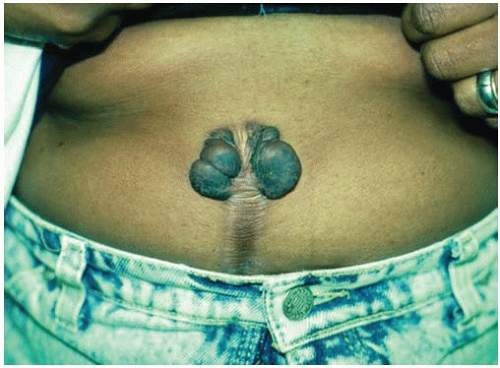

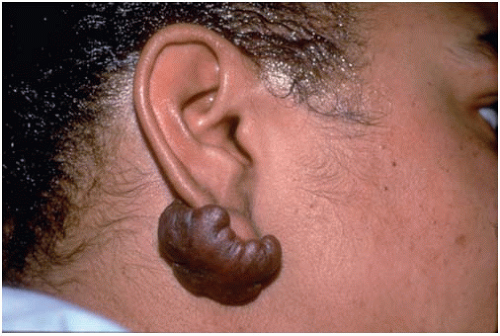

Keloids are usually asymptomatic, although some are pruritic and others may be quite painful and tender (Figs. 25-1 and 25-2). Occasionally, there may be a functional impairment if the scar interferes with movement of the involved area. Keloids start as pink

or red, firm, well-defined, telangiectatic, rubbery plaques that grow beyond the boundaries of the original wound and may become smoother, irregularly shaped, hyperpigmented, firm, and symptomatic.

or red, firm, well-defined, telangiectatic, rubbery plaques that grow beyond the boundaries of the original wound and may become smoother, irregularly shaped, hyperpigmented, firm, and symptomatic.

Figure 25-1. Keloid at ear-piercing site. (From Rubin E, Farber JL. Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999.) |

HSs appear as scars that are more elevated, wider, or thicker than expected and are confined within the size and shape of the inciting injury (Figs. 25-3 and 25-4).

III. WORKUP

The diagnosis of keloids and HSs is usually made with clinical observation; a biopsy will confirm the diagnosis. The patient may give a history of previous trauma, while keloid formation can develop spontaneously with dermatologic diseases like Rubinstein-Taybi and Goeminne syndromes. Other causes, if present, should be investigated and treated aggressively including dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, acne vulgaris, acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, pilonidal cysts, foreign-body reactions, and local infections with herpes virus or vaccinia virus (Table 25-1).

IV. TREATMENT

HSs usually require no treatment and often resolve spontaneously in 6 to 12 months. Intralesional corticosteroid injection is an effective treatment, and excision is another viable option because most HSs do not recur. Pulsed dye laser (PDL) (585 to 595 nm) surgery is also another effective modality; the laser treatment decreases redness and scar mass and improves subjective symptoms. Some clinicians feel that the combination of intralesional steroid and PDL is more effective than either used alone. Keloids are much more difficult to treat because they are not only recalcitrant to various therapeutic modalities but also have a high rate of recurrence (Tables 25-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree