Chapter 70 Infections in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery

Introduction

The low prevalence of this complication limits the experience of any individual surgeon, and the relevant literature consists of few series with small numbers of patients treated with management protocols ranging in aggressiveness from arthroscopic irrigation to radical débridement with graft and hardware removal.1–9

Prevalence of Infection

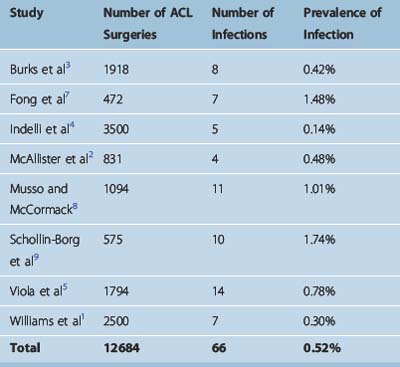

The prevalence of infection following ACL reconstruction is very low. In studies reporting on septic complications, the infection rate ranged from 0.14% to 1.74%1–5,7–9 (Table 70-1). Overall these eight studies reported 66 infections following 12,684 procedures, resulting in a mean infection prevalence of 0.52%.1–5,7–9

Matava et al surveyed directors of sports medicine fellowship programs about their experience with infections after ACL surgery.10 The 61 surgeons who responded performed on average 98 ACL reconstructions per year; 18 surgeons (30%) had treated an ACL infection within the past 2 years, and 26 (43%) had treated an infection within the past 5 years. Therefore even experienced surgeons have managed a limited number of cases in their career.

Pathogenesis: Predisposing Factors

Systemic Factors

The importance of host physiology in musculoskeletal infections has been emphasized in the literature.11 Systemic host factors include comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, malignancy, malnutrition, immunocompromised status, or other disease that may compromise the host defense against microbial pathogens. However, systemic host factors are not as prevalent in ACL surgery compared with other procedures because most patients undergoing ACL reconstruction are relatively young, active, and healthy. In the series with postoperative infections after ACL surgery presented in Table 70-1, the mean age of the patients ranged from 21 to 34 years, and no comorbidities were reported. A study on persistent infections reported comorbidities in three of five patients.6

Local Factors

Local risk factors for infection after ACL reconstruction include previous or concomitant secondary knee procedures.1–3 Williams et al1 reported that six of seven patients with infections had concomitant procedures performed, such as “outside-in” meniscal repair with polydiaxone (PDS) suture, medial collateral ligament reconstruction, and posterolateral corner reconstruction. In the series of McAllister et al,2 three of four patients had previous knee surgery and two of four patients had an “inside-out” meniscal repair. Burks et al3 reported that five of eight patients in their series had concomitant procedures performed at the time of ACL reconstruction. In the series of Musso and McCormack,8 five of nine patients also underwent meniscal procedures.

Potential explanations include the increased operative time, additional or larger incisions with more extensive dissection in cases where complex reconstructive surgery takes place, and implantation of foreign material such as suture. However, other authors did not report concomitant procedures in their infected ACL reconstructions.4 The role of secondary procedures in development of infection is not clear, as the existing studies have not performed a comparison between infected and control patients.

Contamination

Contamination of the operative site may occur from use of inadequately sterilized instruments or implantation of contaminated grafts. Contaminated in-flow cannulas have been identified as the source of infection. Viola et al reported a sudden increase in their infection rate from 0.1% in the period from 1991 to 1996 (2 in 1724 ACL reconstructions) to 14.2% in the period from December 1996 to February 1996 (10 of 70).5 “Sterile” sets of in-flow cannulas used for ACL reconstructions were found to be contaminated with coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. Following the discovery of the contaminated instruments, the infection rate dropped to 0.25% (1 in 400 cases). In another study, contamination with coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was present on supposedly sterile suture clamps on graft preparation boards.9 Inadequate disinfection of arthroscopic equipment12 and flash sterilization of meniscus repair cannulas with residual debris in the lumen13 have been reported as potential causes of septic arthritis following arthroscopy.

Undetected intraoperative contamination of the graft may take place as well. Hantes et al14 obtained culture specimens before implantation of autografts and reported that cultures were positive in 12% of cases (7 of 60). Diaz-de-Rada et al15 reported that allograft cultures were positive in 13% of cases (24 of 181). The source and significance of this contamination remain unclear. However, in both studies no clinical infections developed after a minimum 1-year follow-up. Contamination of allografts used in ACL reconstruction as a source of infection is discussed in detail later.

Biofilm Formation

Biofilm formation is a key mechanism for persistence or recurrence of infection. The biofilm is an aggregation of microbial colonies enclosed within an extracellular polysaccharide matrix (glycocalyx) that adheres on the surface of implants or devitalized tissue.16,17 Gristina and Costerton18 reported that 59% (10 of 17) of orthopaedic biomaterial–related infections had positive findings of glycocalyx-enclosed organisms on electron microscopy. Presence of an avascular graft and metal fixation devices in ACL reconstruction create conditions conducive to biofilm development if a postoperative infection is not treated early and adequately.

The biofilm protects the organism from antibiotics and host defense mechanisms, such as antibody formation and phagocytosis; therefore infection may exist in a subclinical state and eventually recur. In chronic musculoskeletal infections, removal of the biofilm by removal of implants and débridement of devitalized tissue are necessary for successful treatment of infection.19

Diagnosis

Clinical Findings

An alterative presentation is with emergence of symptoms at a later time following a symptom-free interval. In some cases, the clinical picture may consist of mild pain, effusion, and difficulty performing physical therapy without the systemic signs of infection. As Burks et al3 warned, the surgeon should not interpret this relatively benign presentation as the absence of infection. A high index of suspicion is necessary, and patients who do not demonstrate steady postoperative improvement; present with increased pain, effusion, or stiffness following a symptom-free interval; or develop systemic symptoms (fever, chills, malaise) should be considered to have a septic knee until proven otherwise. Patients should be instructed to contact their physician immediately if knee symptoms develop postoperatively, which should be evaluated without delay.

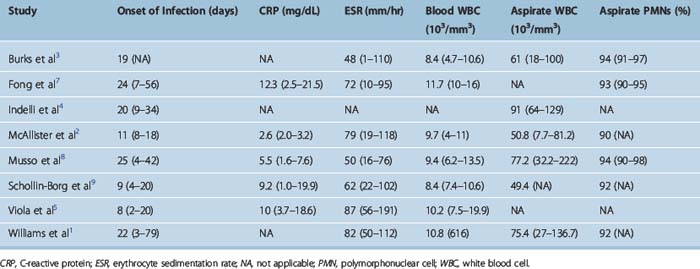

Infections have been classified as acute (presenting less than 2 weeks postoperatively), subacute (2 weeks to 2 months), and late (more than 2 months).1 The mean time for development of infection following ACL surgery ranged from 8 days5 to 25 days8 (Table 70-2).

Laboratory Findings

Peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count may be within normal limits. In contrast, markers of inflammation, such as the C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), are elevated and are helpful in the diagnosis. Elevated CRP has been invariably reported in patients with ACL postoperative infections; the mean CRP levels ranged from 2.6 mg/dL2 to 12.3 mg/dL7 in the existing studies (see Table 70-2). Elevated levels of ESR have been similarly reported in the literature, with mean values ranging from 48 mm/hr3 to 87 mm/hr.5

The anticipated increase of ESR and CRP in the immediate postoperative period may confound the diagnostic picture in the first week. Viola et al5 evaluated 15 patients with a normal postoperative course and reported that 5 days after ACL surgery they had elevated CRP levels with a mean of 2.7 mg/dL (range 0.6–12.3 mg/dL). Margheritini et al20 reported a postoperative increase of both CRP and ESR peaking on the third and seventh days, respectively. The CRP returned to nearly normal levels by postoperative day 15, which was faster than the ESR; the authors concluded that CRP is a more sensitive indicator of postoperative septic complications.20 Elevated levels of CRP beyond the postoperative day 15 strongly point toward a septic etiology for the patient’s symptoms.

Aspiration of the involved knee joint is necessary and yields turbid fluid that should be sent for Gram stain, WBC count and differential, and culture (both aerobic and anaerobic). The mean WBC count has ranged from 49,400 per mm3 in the study by McAllister et al2 to 91,000 per mm3 in the study by Indelli et al.4 Despite this variability in the absolute number of WBC in the joint aspirate, the differential count reveals mean values of 90% to 94% of polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells (see Table 70-2).

Imaging Studies

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help determine the extent of infection and the presence of any extraarticular fluid collections that otherwise could have been missed.21

Microbiology

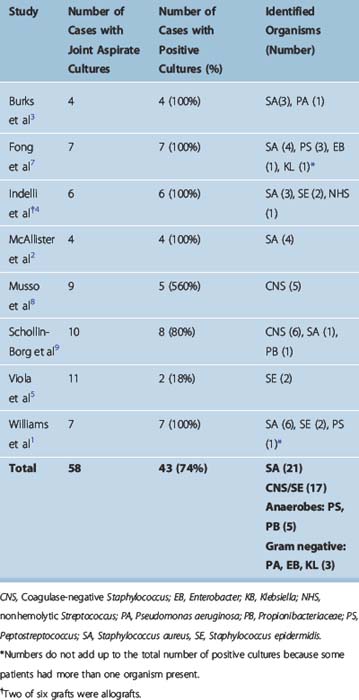

Forty-three (74%) of 58 joint fluid cultures were positive in studies reporting on postoperative autograft ACL infections (Table 70-3). Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen, present in 21 of 43 cases with positive cultures (48.5%). Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (including S. epidermidis) was cultured in 17 of 43 cases (39.5%). Overall, septic arthritis following ACL surgery was caused by staphylococcal species in the vast majority of cases (88%). Anaerobic infections (Peptostreptococcus, Propionibacteriaceae) were present in 11.5% of cases (5 of 43). Gram-negative bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter, Klebsiella) were relatively uncommon and were identified in 7% of cases (3 of 43).

Case reports of unusual infections following autograft ACL reconstruction have been reported, including infection with S. caprae,22Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae,23 mucormycosis,24 and necrotizing fasciitis.25 Reports of infections following allograft ACL surgery are discussed later.

Management Protocol

Surgical Management

Surgical management of septic arthritis with irrigation and débridement of the knee joint is a critical component of the management protocol. Some investigators have suggested that initiation of antibiotics may suffice, and they have proposed an expectant policy, reserving surgical management for cases not responding to antibiotics.5,8 However, this approach has several disadvantages: evacuation of the purulent effusion is incomplete, débridement of the joint is not performed, and thereby an increased bacterial count remains, which may compromise eradication of the infection.

Therefore immediate surgical management has been proposed by several authors.1–3,7,9 In a survey of directors of sports medicine fellowship programs,10 98% of respondents (60 of 61) selected surgical irrigation as part of their management protocol in conjunction with intravenous antibiotics.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree