Vein problems are probably as old as mankind. Surgery on varicose veins was already practiced two thousand years ago at the times of the Roman Empire and what we call now phlebectomy counts among the oldest surgical interventions ever described. Sporadic reports demonstrate that this knowledge was not lost completely in the following 1600 dark years, however the lack of pathophysiological understanding and of adequate anesthesia deprived these early operations of real practical benefit.

The 19 th Century was the start of a scientifically based phlebology. The first injections to treat venous malformations and varicose veins using Pravaz’ newly developed syringes were performed. The availability of anesthesia restarted the interest in vein operations and Trendelenburg described the importance of the reflux circulation within the great saphenous vein (GSV). At the end of the 19 th Century more than hundred vein operations under spinal anesthesia had been performed in Germany, most of them including the ligation of the GSV in mid-thigh following Trendelenburg’s recommendation. The high recurrence rate of this procedure was soon recognized and within a few years German surgeons took the resolution to ligate the GSV directly at the junction. Between 1905 and 1907 the three stripping methods (invagination, ring, ‘olive’) were presented; the Babcock method, being the most reliable, made the race. Atraumatic surgery was not an issue at that time and for many decades to come. It was common use to make incisions of any extent to remove varices and, later on, also for perforating veins. Vein operations had the reputation of being painful and often unsuccessful. No wonder many patients refused an operation and, despite the minor efficacy, preferred their varicose veins to be injected; the rivalry between sclerotherapy and surgery was characteristic for the 1980s and 1990s.

Surgery changed favourably with the re-appearance of phlebectomy, initially propagated by Robert Muller strictly as an ambulatory treatment to avoid vein surgery under stationary conditions. Another turning-point came when ultrasound investigations demonstrated that saphenous incompetence rarely involves the entire vein and that the resection of the GSV or the short saphenous vein (SSV) could be confined to the defective segment, which opened the door to the almost forgotten invagination stripping described by Keller in 1905. Van der Stricht demonstrated this technique to be the least invasive of all stripping methods, but its poor reliability in long stripping prevented its widespread use. Pin stripping developed by Oesch in1992 facilitates invagination stripping by omitting the open preparation at both ends and permits the selective resection of the incompetent vein segments; the shorter resection length helps to reduce the inherent risk of vein rupture. The combination of these technical refinements – tailored stripping, invagination stripping and phlebectomy – substantially diminished the negative side-effects of surgery and contributed to its spreading at the expense of sclerotherapy.

Actual Trends

However, this newly established schedule was not to last for long. New methods to treat saphenous refluxes appeared: Ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, endoluminal laser ablation and, lastly, thermal ablation by steam. The common characteristic of these techniques is the abandonment of the junction closure; the saphenous stem is occluded a few centimetres below. The dogma of the flush ligation, never questioned by surgeons since hundred years, was suddenly abolished. Were the new techniques just making a virtue of necessity? The situation got even more complex with the publication of the CHIVA (Ambulatory Conservative Haemodynamic Management of Varicose Veins) and the ASVAL (Ambulatory Selective Varices Ablation under Local anesthesia) strategies which, in odd contrast, try to preserve the saphenous stems and restrict to selective ligations or resections of tributaries. Amazingly enough all these methods seem to be effective – at least within a time horizon of five years – but we should be aware that it takes more than that before the effects of inaccurate vein treatment will surface. What we can say with certitude is that the appearance of these new techniques induced a sharp decline in stripping operations.

The co-existence of strongly divergent theories and treatments will certainly go on for some time until a clear verdict becomes possible. The scientific eagerness to follow patients for ten years or more is small when only minor complications are at stake; results may be tampered by health systems favouring or penalizing certain methods and by generous industrial sponsoring. Speaking as a surgeon and a sclerotherapist I cannot fully support the idea of abandoning definitely the flush ligation of the junction; I have seen too many recurrent varicose veins originating from untreated side-branches exposed to the pressure of an equally untreated incompetent junction. Most actual ultrasonographic devices used in phlebology do not permit a detailled and precise examination of the highly variable reflux patterns of the junction; the pertinence of these variants and their long-term effects still remain unclear. New technologies developed to investigate cerebral and cardiac circulation will probably by and by trickle down to phlebology and help to close this gap.

Pros and Cons of Surgery

It is true that the principles of ‘classic’ vein surgery go back to the beginning of the 20 th Century, yet the substantial refinements of the last years should not be ignored. Unfortunately non-surgical methods are often compared with the side-effects, complications and long-term results of out-dated operation techniques. On the other hand this unequalled amount of data makes surgery the benchmark for any other method. We have surveys extending for more than thirty years after vein operations. What will be the results of the new techniques after three decades?

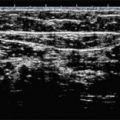

Surgical precision cannot be matched by thermal or chemical actions, where incomplete or excessive effects (as propagation of thrombosis into the deep vein system) have to be excluded by routine ultrasound checks. Injection therapy and heat ablation are typically employed in an outpatient setting, whereas larger surgical treatments require the infrastructure of a hospital and therefore tend to be more time consuming and less cost-efficient. However this difference may dwindle when taking in account that one operation can treat both legs, that there is no need for postoperative ultrasound exams and that retreatment for failure or recurrence is uncommon.

Indications for Surgery Today

•

Phlebectomy

The increasing use of laser and radiofrequency to abolish the reflux in the saphenous vein suggests that the days of venous surgery are definitely over. However, few are the cases where the complete treatment consists in the exclusion of the saphenous vein, since this step by itself has only little impact on the varicose side-branches. The logical therapy in a leg already anesthetized is phlebectomy of the remaining varicose veins. In contrast to sclerotherapy no additional session to treatments or controls are necessary, the vein being physically and definitely removed.

There always will be a place for phlebectomy, be it together with any kind of saphenous treatment, or be it a simple ‘ambulatory phlebectomy’ of isolated varicose veins. Phlebectomy is facilitated when combined with pin stripping. The extraction of the saphenous vein at the distal point of incompetence will also pull out the initial segments of the varicose veins, which permits an easy and complete resection of the entire reflux pathway.

•

Extended varices

Extended bilateral varicose veins can be approached by any available method, as long as the patient consents in a stepwise procedure requiring several sessions. Tumescent anesthesia, a mandatory requirement for endovenous heat obliterations to reduce the risk of skin burns, is limited in its application. Most heat treatments are applied just on one saphenous system at a time to avoid large volumes of anesthetizing solution reaching critical levels. On the other hand a one-step treatment of patients suffering from extended varices is possible by surgery under regional or general anesthesia; in fact most of these patients visit by themselves a surgeon and not a dermatologist. The recovery is not much changed if one or both legs are operated on. In a 2009 survey (Oesch, in press) on 70 patients, a postoperative loss of work of 8.6 days after bilateral surgery was found and of 7.3 days when one leg was treated.

•

Saphenous insufficiency below the knee

Due to the vicinity between the saphenous stems and parallel running nerves any treatment of saphenous veins in the lower leg has a higher risk of nervous complications. The more common injuries of the saphenous nerve due to GSV treatments are rather well tolerated, much in contrast to injuries of the sural nerve following therapeutic procedures on the SSV. The latter tend to be painful for a long time and they may occasionally even end in a law-suit. The critical area for injuries to the sural nerve is the lower part of the calf. Fortunately, often just the upper half of the SSV is incompetent and interventions on the distal part can be avoided.

Selective abolishment of this short upper segment by pin stripping is safe and easy. The SPJ is ligated, a pin-stripper is introduced and the incompetent segment is selectively removed in a quick and safe way. The procedure is almost painless, lesions of the sural nerve occur in well below 1%. A simple local anesthesia is sufficient for stripping and phlebectomy; it is possible to operate both legs in one session.

•

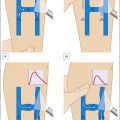

Short proximal reflux

In this situation, only a short part of the saphenous vein needs to be inactivated, e.g. from groin to mid-thigh (about 20% of GSV incompetence) or from the poplitea to mid-calf (about 40% of SSV incompetence). Pin stripping with retrograde insertion of a stripper at the junction permits to spare the intact distal segments. Open preparation of the distal point of incompetence is avoided when using the pin stripping method; which in voluminous thighs is a great benefit for the patient as well for the surgeon.

•

Complex anatomical patterns

Many varices of the thigh are perfused both by the anterolateral vein and the GSV itself; to obtain durable long-term results the two reflux systems should be eliminated. These veins are separated by just a small amount of tissue which would be damaged by aggressive therapies, stripping by invagination is well tolerated. The open resection of the junction often shows an aneurysmatic thin-walled dilatation of the anterolateral tributary and permits the retrograde pin stripping of both veins. This ‘double-stripping’ also reveals the various distal varicose connections between the two reflux systems.

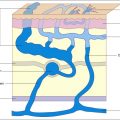

Ultrasound investigations have shown a formerly unknown variety of complex pathophysiological patterns. The reflux is often not confined to the intrafascial GSV; it may switch into large epifascial tributaries and even return distally into the stem. Obliteration of complex reflux pathways without touching the intact segments by endovenous procedures or sclerotherapy is difficult or simply impossible. With the pin-stripper the reflux pathway can be eliminated selectively from proximal to distal by re-introducing the probe at the points where the flow is deviated.

•

Special localizations

Perforators in critical areas such as the knee joint cannot be treated safely by thermal procedures. Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy is often followed by long-lasting clots. Surgery in local anesthesia is well tolerated and usually performed in one session; neurological or other complications are scarce.

Varicose veins originating from the deep-lying and relatively thin Giacomini vein are a therapeutic challenge. Open surgery through a small transverse popliteal incision allows the clear identification of the SSV and the Giacomini vein and an exact closure and resection of the involved vessels. The Giacomini vein is the removed by pin stripping from the popliteal junction to the GSV. Care has to be taken to avoid the introduction of the probe into the deep venous system.

•

Limited financial resources

Endovenous laser and radiofrequency treatment are high-tech procedures. Generators as well as the single-use probes are expensive; an accurate Duplex ultrasound equipment is the prerequisite for any endovenous treatment including foam sclerotherapy. Scarce financial resources limit the wide application of these techniques. Vein surgery can be realized at any place with a few inexpensive and reusable instruments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree