13 Hypopharyngeal, esophageal, and neck reconstruction

Synopsis

Pharyngoesophageal defects are most commonly the result of a total laryngopharyngectomy for squamous cell carcinoma in the laryngeal region or hypopharynx. Other etiology includes benign strictures, pharyngocutaneous fistulas, and thyroid cancer involving the esophagus

Pharyngoesophageal defects are most commonly the result of a total laryngopharyngectomy for squamous cell carcinoma in the laryngeal region or hypopharynx. Other etiology includes benign strictures, pharyngocutaneous fistulas, and thyroid cancer involving the esophagus

Radiotherapy has become the primary treatment for early stages of squamous cell carcinoma in these regions. Many pharyngoesophageal defects are the results of salvage laryngopharyngectomy following a radiation failure, making reconstruction more challenging. Pharyngoesophageal reconstruction requires great attention to detail, and there is no room for error. A small mistake can have a snowball effect and eventually lead to a disaster

Radiotherapy has become the primary treatment for early stages of squamous cell carcinoma in these regions. Many pharyngoesophageal defects are the results of salvage laryngopharyngectomy following a radiation failure, making reconstruction more challenging. Pharyngoesophageal reconstruction requires great attention to detail, and there is no room for error. A small mistake can have a snowball effect and eventually lead to a disaster

Commonly used flaps for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction include the jejunal flap, radial forearm flap, and the anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap. In recent years, the ALT flap has become the most popular flap for this type of reconstruction

Commonly used flaps for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction include the jejunal flap, radial forearm flap, and the anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap. In recent years, the ALT flap has become the most popular flap for this type of reconstruction

Major complications following pharyngoesophageal reconstruction include anastomotic strictures and fistulas. Great care should be taken to minimize these complications

Major complications following pharyngoesophageal reconstruction include anastomotic strictures and fistulas. Great care should be taken to minimize these complications

The ultimate goals of reconstruction are to provide alimentary continuity, protection of important structures such as the carotid artery, and restoration of functions such as speech and swallowing

The ultimate goals of reconstruction are to provide alimentary continuity, protection of important structures such as the carotid artery, and restoration of functions such as speech and swallowing

Most patients (greater than 90%) can eat an oral diet after reconstruction without the need for tube feeding

Most patients (greater than 90%) can eat an oral diet after reconstruction without the need for tube feeding

Speech rehabilitation is typically provided with tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) and fluent speech can be achieved in greater than 80% of patients. Speech quality is superior with a fasciocutaneous flap than an intestinal flap

Speech rehabilitation is typically provided with tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) and fluent speech can be achieved in greater than 80% of patients. Speech quality is superior with a fasciocutaneous flap than an intestinal flap

Many patients with pharyngoesophageal defects have a frozen neck due to previous radiotherapy and surgery, making reconstruction extremely difficult with high surgical risks. Careful planning, use of transverse cervical vessels as recipient vessels, and a two-skin island ALT flap to simultaneously resurface the neck for a through-and-through defect can simplify the procedure and reduce surgical risks.

Many patients with pharyngoesophageal defects have a frozen neck due to previous radiotherapy and surgery, making reconstruction extremely difficult with high surgical risks. Careful planning, use of transverse cervical vessels as recipient vessels, and a two-skin island ALT flap to simultaneously resurface the neck for a through-and-through defect can simplify the procedure and reduce surgical risks.

Introduction

• A noncircumferential esophageal defect should not be converted to a circumferential one as was commonly done when the jejunal flap was popular. Reconstruction of partial defects rarely results in anastomotic strictures.

• Distal flap-esophageal anastomosis should be spatulated to minimize stricture formation in circumferential defects.

• A layer of well-vascularized fascia of the ALT flap can be used to cover the suture lines, especially the distal anastomosis, to minimize the risk of anastomotic leakage and pharyngocutaneous fistula formation.

• Fasciocutaneous flaps provide better speech function than intestinal flaps.

• High-risk patients with significant comorbid diseases are relative contraindications for jejunal flap reconstruction. Fasciocutaneous flaps have much lower systemic morbidity.

• While bowel heals quickly when used for esophageal reconstruction, fasciocutaneous flaps may experience delayed healing when being soaked with saliva 24 hours a day, which may explain some delayed fistulas. Therefore delayed oral intake is recommended, particularly in radiated patients.

• Proper management of postoperative complications is important to prevent life-threatening sequelae and maximize function.

Historical perspective

The first esophageal resection was reported by Billroth1 in dogs in 1871 while the first successful cervical human esophageal resection was reported by Czerny2 in 1877, in which a spit fistula was created in the upper neck and a distal cervical esophagocutaneous fistula was created for feeding purpose. The first reported cervical esophageal “reconstruction” was documented by Mikulicz3 in 1886 in which the proximal and distal cervical esophageal ends were connected with a rubber tube over the neck skin and the skin was later tubed to close the gap. Similar techniques using local skin were reported in the early 1900s.4–6 Based on these early experiences using local skin, Wookey (1942) successfully completed a staged reconstruction of the cervical esophagus using laterally based horizontal skin flaps in a tubular form.7,8 The disadvantages included the need for multiple-stage procedures, limited amount of available skin, poor quality of skin after radiotherapy, thus high rates of wound complications and fistula formation. The Wookey flap and its variations9–11 were popular until the 1960s when Bakamjian12 described the use of the deltopectoral flap for cervical esophageal reconstruction. Compared to previous random skin flaps, the deltopectoral flap is an axial pattern flap supplied by the internal mammary artery perforators except the distal part over the deltoid region. The other advantage is that the flap skin is usually outside the radiation field. Although this technique significantly reduced mortality and fistula rate (30%), distal flap necrosis was common and multistage reconstruction was also required. Due to the limitations of the above techniques, they are no longer used for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction today.

Other early techniques for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction besides skin flaps were also described.

In the early to mid-1900s, simple placement of rigid stents/mesh materials with or without internal skin grafting was described.13–19 These techniques were usually complicated with loss of skin grafts, fistula formation, and stricture formation with low success rates, as one would imagine. The gastric pull-up procedure was introduced in the mid-1900s to reconstruct thoracic esophagectomy defects and was later used for pharyngoesophageal defects.20–28 Subsequently, the pedicled colon and jejunum also became popular flaps for such reconstructions.29–31 Although one-stage reconstruction could be accomplished with these techniques, removing the normal thoracic esophagus and using this technique only to reconstruct a pharyngeal and cervical esophageal defect are rather “inefficient” techniques with high surgical risks. These techniques have also been abandoned for pharyngeal and cervical esophageal reconstruction with the development of myocutaneous flaps and subsequent free flaps.

The development of myocutaneous or muscle flaps revolutionized head and neck reconstruction. In particular, the pectoralis major muscle or myocutaneous flap32–36 is one of the most commonly used flaps for head and neck reconstruction and is still commonly used today. Because of the rich blood supply and single-stage reconstruction, the pectoralis major flap became the flap of choice for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction until free flaps became popular in the 1980s. Disadvantages of the pectoralis major flap included its limited use for circumferential defects due to its bulk, difficult skin paddle inclusion in women, downward-pulling force causing proximal dehiscence, relatively high fistula rate, neck contour deformity, and donor site deformity.

The next revolution in head and neck reconstruction is the development of free tissue transfers. Seidenberg et al.37 reported the first clinical use of free jejunal flaps for cervical esophageal reconstruction in 1959. Several more successful jejunal flap reconstructions were reported in the 1960s.38–40 Although these early reports demonstrated a possibility of this technique, the lack of proper magnification, microsurgical instrucments, and sutures severely limited its use until the 1980s. The free jejunal flap enjoyed its popularity since the early 1980s and became the “gold standard” for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction in many centers.41–49

Although the jejunal flap has several advantages, such as rapid healing, low fistula rate, and no need to form a tube at the time of surgery, its abdominal morbidity and poor speech reproduction with TEP techniques make it less ideal for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction. Fasciocutaneous flaps such the radial forearm flap remain a commonly used flap by many, although it has a reputation of having high fistula rates.50–53 Since the beginning of the 21st century, however, the ALT flap has largely replaced both the jejunal and radial forearm flaps for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction and has become the new “gold standard” in many centers due to its many advantages.54–59

Basic science/anatomy

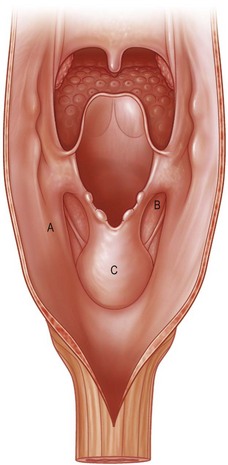

The pharynx is anatomically divided into the oropharynx, nasopharynx, and hypopharynx. The nasopharynx is essentially the structures around the nasal cavity above the soft palate. Its defects are usually the result of a maxillectomy and will be discussed elsewhere. The oropharynx is bounded by the nasopharynx superiorly, the oral cavity anteriorly, and the hypopharynx and larynx inferiorly. The superior border of the oropharynx is at the plane of the soft palate, and the inferior border is defined by the level of the hyoid bone. The main structures in the oropharynx are the base of tongue, tonsillar pillars, lateral and posterior oropharyngeal walls, and soft palate. Common oncologic defects in the oropharynx are the result of surgical resections of cancers in the base of tongue, which frequently extend to the lateral pharyngeal wall, or cancers in the tonsillar pillar extending to the soft palate. Cancers in the maxilla or parotid region with extension into the pterygoid or buccal spaces also require resection of the oropharynx, including the tonsillar pillars, lateral pharyngeal wall, soft and hard palate, and posterior mandible. The hypopharynx extends from the level of the hyoid bone to the lower border of the cricoid cartilage, which is congruous with the cervical esophagus below (Fig. 13.1). This is a critical area that is responsible for airway protection and swallowing and speech functions. Common defects of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus are the result of surgical resection of cancers in the hypopharynx and larynx, advanced thyroid cancers, radiation strictures, and chemical injuries. Isolated tumors in the cervical esophagus, although rare, may also require segmental esophagectomy and reconstruction (Table 13.1). Pharyngoesophageal defects can be circumferential or partial (Fig. 13.2).

Table 13.1 Types of pharyngoesophageal defect requiring reconstruction

| Pathology | Defect location | Type of defect |

|---|---|---|

| Primary SCC | Hypopharynx and cervical esophagus | Most commonly partial |

| Recurrent SCC | Hypopharynx and cervical esophagus | Most commonly circumferential |

| Advanced or recurrent thyroid cancer | Hypopharynx and cervical esophagus | Most commonly circumferential |

| Isolated esophageal tumors | Cervical esophagus with an intact larynx | Most commonly partial |

| Pharyngoesophageal or tracheoesophageal fistulas | Cervical esophagus or hypopharynx | Most commonly partial |

| Anastomotic strictures | Cervical esophagus | Most commonly circumferential |

| Radiation-induced strictures | Hypopharynx or cervical esophagus | Partial or circumferential, depending on the degree of stricture |

SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Patient selection

Preoperative evaluation

Donor site evaluation

Common donor sites such as the thigh, forearm, abdomen, and anterior chest should be evaluated for skin quality and thickness, history of surgery or trauma, and vascular disease. The subcutaneous tissue in the thigh in female patients is usually twice as thick as in male patients,60 therefore, considerations should be given when choosing a flap. Allen’s test is commonly used to assess the adequacy of hand perfusion through the ulnar artery when reconstruction with a radial forearm flap is planned. A bracelet with the words “NO IV” is placed on the potential donor site arm, which is usually the one with the nondominant hand. Previous abdominal surgery and severe comorbid diseases are relative contraindications for a jejunal flap. Careful planning is essential for successful reconstruction. One should always have a “plan B” or even “plan C” for complex cases.

Choice of flaps

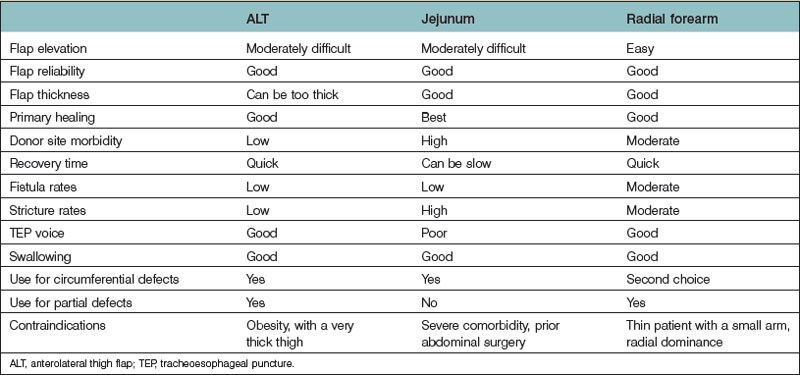

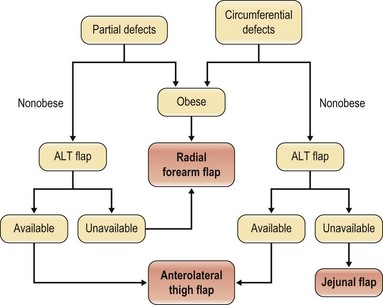

With the advances in microsurgery, free-flap reconstruction has largely replaced pedicled flaps for large head and neck oncological defects, especially those with prior radiotherapy, which renders pedicled flaps unreliable. The thoracic skin flap once used in the 1950s and the deltopectoral flap developed in the 1960s are no longer used for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction in modern-day practice. The only pedicled flap that still plays a role either as a primary reconstruction or as a salvage procedure is the pectoralis major flap which gained popularity in the early 1980s. Although it is easy to harvest, no microsurgical skills are required, and it may work well in experienced hands for partial pharyngoesophageal defects in male patients, the flap can be bulky, the skin paddle can be unreliable especially in smokers, fistula rate can be high, and functional outcomes may not be as good. Common free-flap options include the radial forearm flap, the jejunal flap, and, more recently, the ALT flap. Although reliable and easy to harvest, the radial forearm flap traditionally has a reputation of having high fistula rates, especially delayed fistulas. The jejunal flap enjoyed its reliability and became the flap of choice for circumferential pharyngoesophageal defects in the early 1990s. The major disadvantage is the added abdominal surgery. Since the ALT flap was first used for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction at our institution in early 2002 by the author,54 it quickly gained popularity and replaced both the radial forearm and jejunal flaps as the flap of choice for both partial and circumferential defects. The advantages and disadvantages of each flap are listed in Table 13.2. An algorithm for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction is outlined in Figure 13.3.

If the ALT flap is unavailable owing to a lack of perforators, the jejunal flap is the next choice for repair of circumferential defects in patients at low risk. In patients who are at high risk or obese or who have a history of abdominal/gastrointestinal surgeries and for partial defects, the radial forearm flap is the next choice. The pectoralis major flap can be used for partial defects in male patients, for salvage after failed free-flap reconstruction, or in very high-risk patients. In our recent experience of 119 pharyngoesophageal reconstructions,59 the ALT flap was used in all but 5 patients. In these 5 patients, the ALT was deemed too thick or unavailable upon exploration.

Surgical technique

Reconstruction with the anterolateral thigh flap

Flap design and harvesting

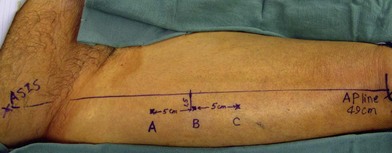

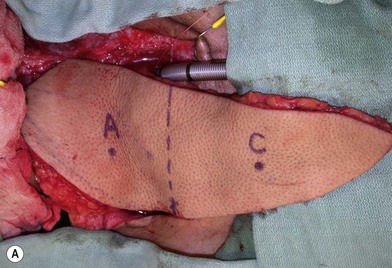

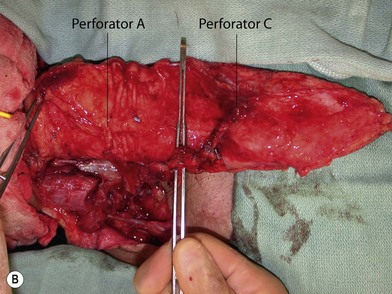

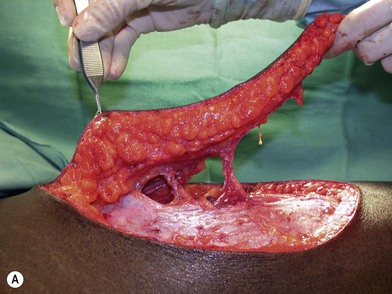

Once the legs are in the correct position, the anterior superior iliac spine and the superolateral corner of the patella are marked and a straight line is drawn connecting the two landmarks – the anteroposterior (A-P) line. The midpoint of the A-P line is then marked. There are usually one to three usable cutaneous perforators in the ALT flap territory. The middle perforator, perforator B, is located an average of 1.4 cm lateral to the midpoint of the A-P line.60,61 Perforator A is located approximately 5 cm proximal to perforator B, and perforator C is 5 cm distal to perforator B (Fig. 13.4). The flap design is centered on the presumed location of perforator B. Doppler examination can be used to help locate the cutaneous perforators. However, the accuracy is only fair. The false-positive rate can be high, and more than 25% of Doppler signals are more than 10 mm away from the actual location of the cutaneous perforator. The accuracy is particularly poor in obese patients.61 We have found that localization of the perforators based on this “ABC” system is more accurate than hand-held Doppler examination.

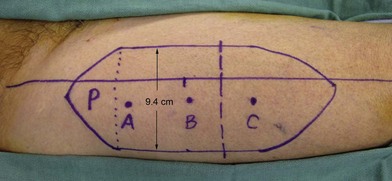

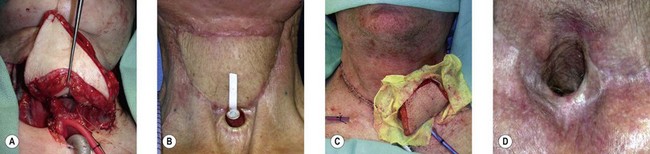

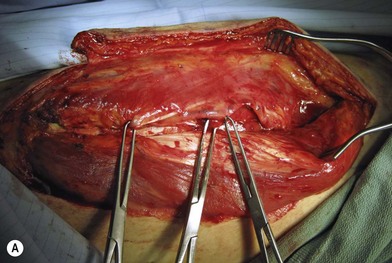

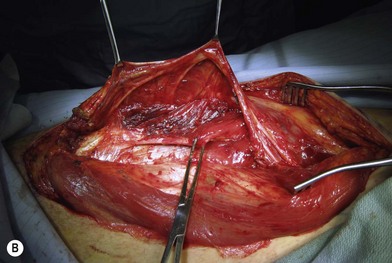

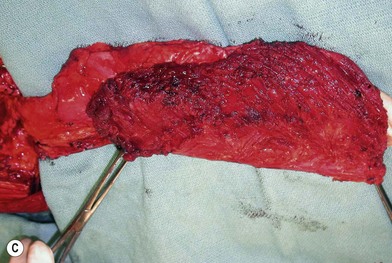

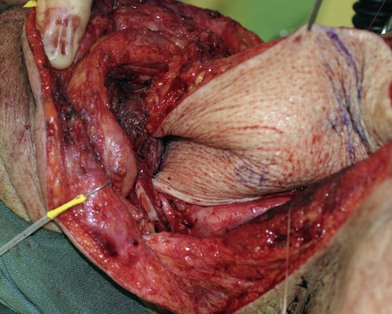

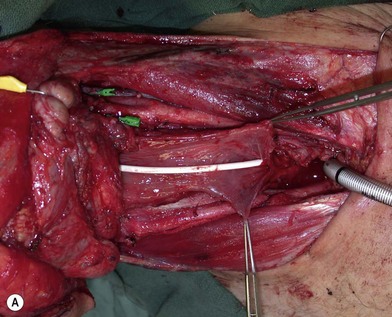

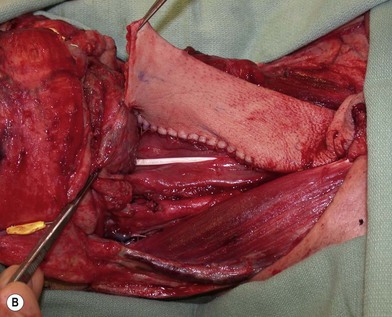

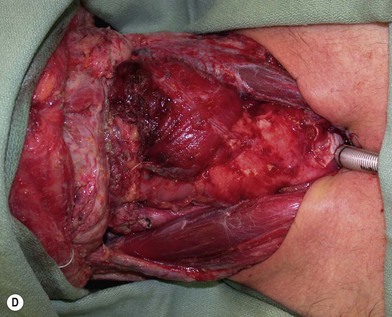

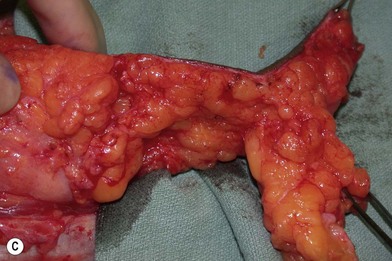

Flap elevation is performed simultaneously with tumor ablation using a two-team approach. The reconstructed neoesophagus should have a diameter of 3 cm. Therefore, for circumferential defects, a flap 9.4 cm wide is needed to form a 3-cm-diameter (3 × π) tubed neoesophagus (Fig. 13.5).54 For partial defects, the width of the flap is calculated by subtracting the width of the remaining pharyngeal mucosa from 9.4 cm. For example, if the remaining mucosa is 2 cm wide, the needed flap width would be 7.4 cm. The flap length should be slightly longer than the actual defect but the two ends should be tapered and included in the flap design. Flap design is tentatively centered on the presumed perforator B location. A straight anterior incision approximately 15 cm long is made first across all three cutaneous perforators down to the fascia. This incision corresponds to the anterior midline of the thigh in most cases. A wider fascia is included for second-layer closure during flap insetting. Therefore, the fascial incision is made 1–2 cm more medially than the anterior skin incision (Fig. 13.6). Subfascial dissection proceeds laterally until the cutaneous perforators are identified. The exact locations of the perforators are marked on the skin surface with a 5-0 polypropylene suture. The flap is then recentered, if necessary, on the basis of the actual perforator locations. To accommodate the wide opening in the pharyngeal inlet for the proximal anastomosis, an extended lip of skin is designed at the proximal end of the flap so that an elongated oblique opening can be created when the flap is tubed (Figs 13.15 and 13.7). Dissection of the perforators and the main pedicle can be performed through the anterior incision only. The remaining flap is incised only after the cutaneous perforators and the main vascular pedicle are located or dissected out. Two cutaneous perforators are included whenever possible so that the flap can be divided into two skin paddles (Fig. 13.8). The proximal one, usually based on perforator B or A, is used for reconstruction of the pharyngoesophageal defect, and the distal one, usually based on perforator C, is used for flap monitoring or for anterior neck and tracheal reconstruction (Fig. 13.9). If only one perforator is present and there is an anterior neck defect to be reconstructed, a segment or the superficial half of the vastus lateralis muscle is included in the ALT flap to support skin grafts to resurface the neck, eliminating the need for a second flap.62 This layer of muscle is usually no more than 1 cm thick, and usually a better option than a pectoralis major muscle flap (Fig. 13.10). The descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery usually travels within the muscle, and the surgical plane of dissection is immediately deep to the descending branch, splitting the muscle.

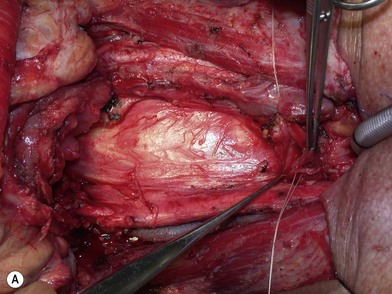

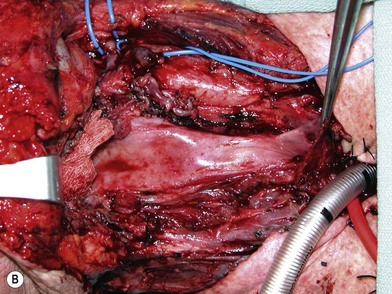

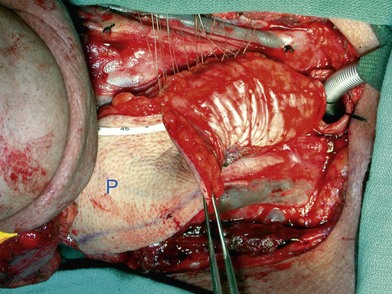

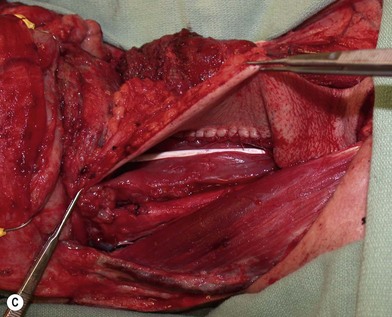

Flap insetting

Partial or complete flap insetting is performed before vascular anastomosis to avoid accidental traction injury to the vascular pedicle. In most cases, the proximal anastomosis of the flap with the base of tongue and posterior pharyngeal mucosa is performed first (Fig. 13.11). If the flap is longer than the defect, the perforator of the flap should be placed near the center of the defect and extra flap trimmed if necessary. Although some surgeons prefer tubing the flap in the thigh before transfer, I find it is easier to perform the proximal anastomosis without tubing the flap first. I usually use a 3-0 polyglactin suture in a simple, interrupted fashion. The longitudinal seam is oriented posterolaterally at 4 or 8 o’clock (Fig. 13.11). The anastomosis starts with two corner sutures at 3 and 9 o’clock. The posterior wall is then completed, followed by the anterior wall. Large bites are recommended with inversion of the skin and mucosal edges into the lumen. Care should be taken to avoid catching the hypoglossal nerve when suturing the flap to the base of the tongue. Next, the longitudinal seam is completed towards the distal end of the flap, also with simple, interrupted sutures. For partial defects, the proximal end of the flap is sewn to the base of the tongue and the lateral edges to the remaining posterior pharyngeal wall mucosa (Fig. 13.12).

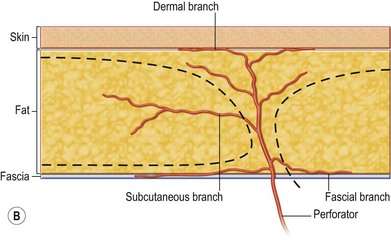

The ALT flap in most patients is thicker than desired. The flap can be thinned by direct excision of subcutaneous fat at the periphery of the flap. In most cases, this is all that is needed for thinning. Peripheral thinning makes flap insetting much easier without jeopardizing the perfusion. When more aggressive thinning is needed, the perforators should be well visualized either with loupe magnification or under the microscope when they enter the flap and are traced within the subcutaneous tissue. The perforators usually divide into fascial branches, subcutaneous branches, and the main branch terminates in the subdermal plexus (Fig. 13.13). These branches may take an oblique course within the subcutaneous tissue in a thick flap. Blindly trimming the fat around the main perforator may damage the branches within the flap and compromise the perfusion. Ample subcutaneous tissue should be left around the cutaneous perforators, and 2–3 mm of subcutaneous tissue is left on the dermis to protect the subdermal plexus (Fig. 13.13).

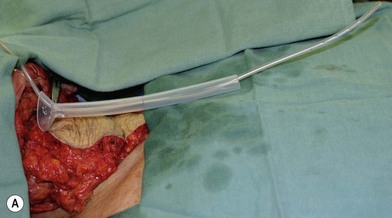

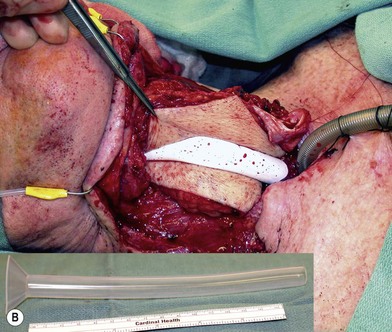

Some surgeons advocate the use of the Montgomery salivary bypass tube in circumferential defects potentially to decrease the incidence of leak and stricture. The value, however, is unclear. In my experience, the indications for the use of the Montgomery tube include: a thick flap (narrow lumen), difficult flap insetting, very low location of the transected cervical esophageal end, small cervical esophagus, or poor tissue quality due to radiation injury. A 14-mm-diameter Montgomery salivary bypass tube is used. The tube is inserted through the mouth before the longitudinal seam of the flap is completed (Fig. 13.14). The proximal flange of the bypass tube is placed above the proximal anastomosis and the distal end in the esophagus below the distal anastomosis. A number 1 polypropylene suture is attached to the flange of the tube, brought out through the mouth, and taped to the cheek to prevent distal migration and facilitate easy removal of the tube. If a feeding tube has not yet been placed, a Dobhoff feeding tube is placed through the nose, the tubed flap, or inside the Montgomery salivary bypass tube, and the cervical esophagus to the stomach.