The physical examination was a major tool in the diagnosis of disease prior to the widespread availability of diagnostic laboratory tests and imaging. Many evaluations and diagnoses are now made in the absence of an extensive physical examination and history.1,2 Most skin diseases, however, are still diagnosed on the basis of a careful physical examination and history.

Typically the history and physical examination for the skin is done in the same sequence and manner as with any other organ system. In some cases it is helpful to examine the patient after taking only a brief history so the questions for the patient can be more focused.3

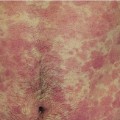

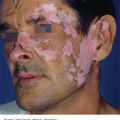

A problem-focused history is sufficient for most common skin disorders. If, the patient has systemic complaints, or if diseases such as lupus erythematous or vasculitis are suspected, a detailed or comprehensive history may be needed.

Ask about:

Initial and subsequent morphology and location(s) of lesions

Symptoms (eg, itch, pain, tenderness, burning)

Date of onset and duration

Severity and factors causing flares

Medications (including over-the-counter products) used for treatment and response to treatment

History of previous similar problem.

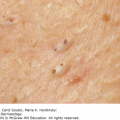

If the patient’s chief complaint is a skin tumor/growth, the following additional questions should be added. With the increasing incidence of skin cancer, these questions could be added in any patient’s history:

What changes have occurred the size and appearance of the lesion?

Is there a history of spontaneous or trauma-induced bleeding in the lesion?

Is there a history of sunburns or tanning bed use?

Is there a history of sunscreen use?

It is also important to determine the patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type, as this helps to identify patients at risk for skin cancer (Table 3-1). Patients should be asked if they burn easily or tan after their initial exposure to sunlight.4 The patient’s response determines his or her Fitzpatrick skin type. Typically there is a correlation between a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type and his or her skin color.

If indicated, the patient should also be asked about the effect of his or her skin condition on work and social and home life. The Dermatology Life Quality Index at www.dermatology.org.uk has a 10-point questionnaire that can be used to more accurately assess a patient’s quality of life concerns. Skindex is another widely used instrument for quality of life evaluations.5

Ask about past and current diseases, personal history of skin cancer, and other skin disorders.

Ask about a family history of skin cancer, atopy (atopic dermatitis, rhinitis, and asthma), psoriasis, autoimmune diseases, or any disorder similar to the patient’s skin problem.

Ask about patient’s occupation, hobbies, and travel.

Ask about fever, chills, fatigue, weight changes, lymphadenopathy, joint pains, wheezing, rhinitis, menstrual history, birth control methods, depression, and anxiety. Additional ROS questions can be asked based on the patient’s chief complaint.

Ask about the use of all systemic and topical medications including over-the-counter medications and supplements.

Ask about adverse reaction to medications, foods, and pollens.

A careful, systematic examination of the skin, hair, and nails is an essential and cost-effective method for the evaluation and diagnosis of skin disorders. It is important to examine the skin for lesions that are directly related to the chief complaint and for incidental findings, especially for lesions that may be skin cancer. A study done in a dermatology clinic in Florida found that 56.3% of the melanomas that were found during a full-body skin examination were not mentioned in the patient’s presenting complaint.6 A full-body skin examination can easily be incorporated into the routine examination of other areas of the body.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree