Hematologic Diseases: Introduction

|

Hematology includes the study of blood and blood-forming tissues. Given the number and variety of hematologic disorders, it is not surprising that mucocutaneous manifestations of hematologic disorders are common. Many hematologic malignancies and pseudomalignancies can involve the skin through atypical cell infiltration (specific lesions), and some of these may present preferentially in the skin. These conditions, such as leukemias and lymphomas, plasma cell dyscrasias including myeloma, and Langerhans and non-Langerhans histiocytoses, are discussed in other chapters. Likewise, complications of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, cytokine use, or marrow transplantation are discussed elsewhere.

The first section of this chapter is directed toward the differential diagnosis of purpura with an emphasis on those subsets of purpura with important underlying hematologic abnormalities. The second major section of this chapter is directed toward nonspecific (nontumor-containing) findings that may be associated with hematologic disorders. Although the ready availability of laboratory testing has made early recognition of such conditions as anemia and polycythemia much less dependent on physical findings, cutaneous associations still may aid in the diagnosis of a hematologic condition or complicate its management. A comprehensive listing of these associations is presented in Table 144-1.

Pigmentary Changes

|

Recurrent Cutaneous Infections

|

Neutrophilic Cutaneous Reactions

|

Vesiculobullous Disease

|

Vascular Disorders and Coagulopathies

|

Cutaneous Deposition/Induration/Altered Texture3,4

|

|

Cutaneous Sarcoidal or Histiocytic Tissue Reactions

|

Epidermal Changes

|

Hypertrichosis

|

Pruritus, Prurigo, and Burning

|

Ulcerations

|

Hemostasis and the Differential Diagnosis of Purpura

Hemostasis can be defined as the arrest of bleeding, and has two phases, primary and secondary, though research findings are blurring the compartmentalization of this process.65 Primary hemostasis depends both on the vasoconstriction of the injured vessel and on formation of a platelet plug at the injury site. It is usually sufficient for focal microcirculatory injury repair. Larger defects or injury in larger cutaneous vessels require secondary hemostasis to reinforce the platelet plug.

Primary hemostasis is characterized by vascular contraction, platelet adhesion and activation, and subsequent development of a plug at the site of vessel injury. Vascular contraction leads to slowing of the blood flow, so the platelets can adhere to the injured site and diminish blood loss.66 Secondary hemostasis promotes vascular integrity when primary hemostasis is insufficient and when larger vessels are involved. This phase maintains vasoconstriction through the secretion of prostaglandins, thromboxane, and serotonin. It also solidifies the platelet plug formed during primary hemostasis, through a series of clotting cascade pathways.

Because of the rich and highly visible nature of the skin microcirculation, and because of the very dynamic alterations of cutaneous blood flow (e.g., increasing to promote heat exchange, decreasing dramatically in shock states) as well as hydrostatic pressure variations by anatomic site and body position, the skin can be a very early and sensitive locale for signs of hemostatic alterations and coagulopathy. In nondisease states, the blood participates in an ongoing homeostatic balance between site-specific hemostasis or clot formation, clot extension inhibition, and clot lysis at the appropriate stage of injury repair. The platelet and coagulation cascade participate in clot formation, the antithrombin III and thrombomodulin/protein C/protein S systems in clot inhibition, and the plasminogen/plasmin system in clot lysis.

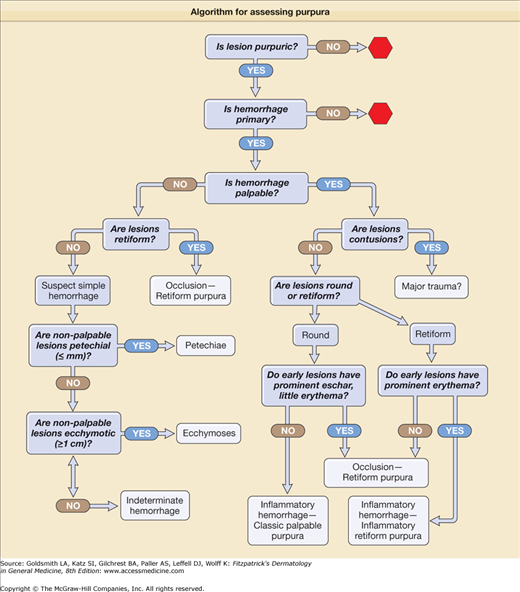

The bedside dissection of the likely differential diagnosis of purpura can be summarized by five Ps: are lesions purpuric, primary, palpable, and what is their pattern and placement? For a lesion to qualify as purpuric, it must have a color that is compatible with hemorrhage—usually some shade of red, blue, or purple, but sometimes yellow–brown, green, or black—and at least some of this color must persist on compression of the skin. If the vessels are compressible, and if the color is due to mobile red cells within the vessels, then the skin color should completely blanch on compression, and no hemorrhage is clinically evident. False-positive results occur if the lesions contain tortuous vessels that kink on compression, or if compression is incomplete. Extravasated cells are not free to move, and therefore color persists on compression. It is important not only to determine the persistence of some color on compression, but also to assess in early lesions the proportion of erythema to hemorrhage. Complete blanching is a nonpurpuric lesion, but may be the physical presentation of mild urticarial vasculitis with clinically nonevident hemorrhage. Significant partial blanching of early lesions suggests an inflammatory etiology of the purpuric process. No detectable color change suggests no inflammatory component, and is characteristic of simple hemorrhage and most microvascular occlusive lesions.

Purpura may be primary or secondary in etiology. Hemorrhage may occur in inflammatory syndromes such as cellulitis, psoriasis, stasis dermatitis, or eczema, and these should be considered secondary purpura syndromes. In these and similar settings, the hemorrhage is generally secondary to nonvessel-directed inflammation increasing vascular permeability, and usually hydrostatic pressure increasing the likelihood of incidental red cell extravasation in areas of dependency.

Palpability rarely reflects the amount of cutaneous hemorrhage except for very large and deep focal cutaneous hemorrhage, resulting in a hematoma typically localizing in or below the fat layer of skin. Upward movement of the hemorrhage may occasionally result in an overlying ecchymosis. Most simple hemorrhage in the skin is nonpalpable. Instead, palpability typically results from protein-rich edema secondary to inflammation or microvascular ischemia with vascular and tissue injury. While the presence of palpability should exclude simple hemorrhage as a pathogenesis, the absence of palpability does not exclude inflammatory or occlusive hemorrhagic etiologies.

Many approaches to the differential diagnosis of purpura begin with pathophysiologic mechanisms. However, pathophysiology is usually what the physician is attempting to ascertain, and the diagnostic process begins with clinical clues. Some of the most important clinical information available from the bedside examination is lesional number, distribution, and morphology. Exploration of the differential diagnosis can begin with helpful patterns of lesional number and distribution are listed in Table 144-2.

Distribution/Number Pattern | Distribution | Number of Lesions | Most Common Etiologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | Gravity-dependent increasing density of lesions | Few to few 100s | Platelet-dependent hemostatic failure |

| Immune-complex vasculitis | |||

| Minor Trauma-Prone areas | Extensor surface of arms, lateral thighs, anterior lower legs | One to a dozen | Extensor arm only suggests actinic purpura; multiple areas suggest minor trauma ecchymosis differential in Table 144-3 |

| Multigeneralized | |||

| Multigeneralized with round lesions | Generalized eruption | Many 100s | Usually drug or viral eruptions |

| Multigeneralized with retiform lesions | Widespread eruption | Few to Fifty | Sepsis-related microvascular occlusion/purpura fulminans |

| Pauci-random | Random localization | Few | Nonimmune complex vasculitis, especially ANCA +; Systemic microvascular occlusive disease |

| Acral | |||

| Acral: erythema multiforme type | Involves hands and feet, with or without a more generalized distribution | Few on hands/feet, may have many more if accompanied by a generalized eruption | Usually drug or viral eruption, especially recurrent HSV eruptions |

| Acral: cold-localized type | Hands, feet, nasal tip, ears | Few | Cold-occlusion phenomena |

| Acral: hypotensive, | Digital gangrene, or retiform purpura on hands and/or feet | Few | Shock, usually in association with vasoconstrictor administration and sepsis-related coagulopathy |

| Acral: feet with livedo reticularis extending proximally | Livedo reticularis of legs often prominent early, expect few distal retiform purpura lesions3 | Few purpura lesions | Cholesterol embolus, can be mimicked by antiphospholipid antibody syndrome |

| Acral: wedge-shaped | Distal, usually one limb or digit | One wedge-shaped lesion | Arterial occlusion |

The initial diagnostic considerations based on these patterns should then be combined with information gleaned from the lesional morphologic differential diagnosis (Tables 144-3, 144-4, and 144-5; Fig. 144-1).

|

Classical Palpable Purpura (Round, Port-Wine Color, Partially Blanchable Early) Morphology of early lesion: prominent erythema with palpable purpura suggests inflammatory hemorrhage

|

Inflammatory Retiform Purpura Morphology of early lesion: prominent erythema with retiform purpura suggests subset of inflammatory hemorrhage (and, rarely, ischemic syndromes)

|

Morphology of early lesion: minimal erythema with retiform purpura or with necrosis suggests occlusion with ischemic hemorrhage or infarction.

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree