Helminthic Infections: Introduction

|

Helminths (worms) are variably sized multicellular parasites that can infect a wide range of mammals, including humans. Those causing human disease belong to three groups: (1) nematodes (roundworms), (2) trematodes (flukes), and (3) cestodes (tapeworms) (Table 207-1); trematodes and cestodes are collectively referred to as platyhelminths (flatworms). This chapter focuses only on those helminths that more commonly cause dermatologic disease.

Helminth | Disease | Portal of Entry | Source of Infection |

|---|---|---|---|

Nematodes (Roundworms)—Intestinal | |||

Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus | Hookworm | Skin | Larvae in soil, occasionally in food |

Ascaris lumbricoides | Ascariasis | Gastrointestinal | Eggs from contaminated food, soil |

Enterobius vermicularis | Enterobiasis (pinworm) | Gastrointestinal | Eggs in environment |

Strongyloides stercoralis | Strongyloidiasis | Skin | Larvae in soil |

Nematodes (Roundworms)—Tissue | |||

Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma caninum | Cutaneous larva migrans | Skin | Larvae in soil |

Dirofilaria spp. | Dirofilariasis | Skin | Infective mosquitoes |

Dracunculus medinensis | Dracunculiasis | Gastrointestinal | Infective copepods in water |

Filariae | |||

Brugia malayi, Brugia timori | Filariasis | Skin | Infective mosquitoes |

Mansonella ozzardi, Mansonella perstans, Mansonella streptocerca | Filariasis | Skin | Infective midges and/or flies |

Loa loa | Loiasis | Skin | Infective deer flies |

Onchocerca volvulus | Onchocerciasis | Skin | Infective black flies |

Wuchereria bancrofti | Filariasis | Skin | Infective mosquitoes |

Gnathostoma spinigerum, others | Gnathostomiasis | Gastrointestinal | Larvae in animal flesh (raw fish, amphibians) |

Toxocara canis, Toxocara cati | Visceral larva migrans | Gastrointestinal | Eggs in contaminated food, soil |

Trichinella spiralis | Trichinosis | Gastrointestinal | Larvae in animal flesh (usually pork, bear) |

Trematodes (Flukes) | |||

Clonorchis sinensis | Clonorchiasis | Gastrointestinal | Metacercariae in seafood (raw fish) |

Fasciola hepatica, others | Fascioliasis | Gastrointestinal | Metacercariae on watercress, in water |

Fasciolopsis buski | Fasciolopsiasis | Gastrointestinal | Metacercariae on plants, in water |

Heterophyes heterophyes | Heterophyiasis | Gastrointestinal | Metacercariae in seafood (raw fish) |

Metagonimus yokogawai | Metagonimiasis | Gastrointestinal | Metacercariae in seafood (raw fish) |

Paragonimus westermani, others | Paragonimiasis | Gastrointestinal | Metacercariae in seafood (crabs, crayfish) |

Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma japonicum, others Schistosomes, non-human (avian) | Schistosomiasis Cercarial dermatitis | Skin Skin | Cercariae in water Cercariae in water |

Cestodes (Tapeworms) | |||

Diphyllobothrium latum (fish tapeworm) | Diphyllobothriasis | Gastrointestinal | Larvae in seafood (raw fish) |

Echinococcus spp. | Echinococcosis (hydatid disease) | Gastrointestinal | Eggs in contaminated food |

Hymenolepis nana (dwarf tapeworm) | Hymenolepiasis | Gastrointestinal | Eggs in contaminated food, water |

Spirometra mansonoides, others | Sparganosis | Gastrointestinal | Larvae in contaminated water or animal flesh (snakes, amphibians, fish) |

Taenia multiceps, others | Coenurosis | Gastrointestinal | Eggs in contaminated food, water |

Taenia saginata (Beef tapeworm) | Taeniasis | Gastrointestinal | Larvae in contaminated food (beef) |

Taenia solium (Pork tapeworm) | Taeniasis; cysticercosis | Gastrointestinal | Larvae in contaminated food (pork) |

Epidemiology

Globally, helminthic infections are among the most common diseases of humans. However, the true prevalence of helminthiases is difficult to determine, particularly since the majority of infected individuals harbor relatively few worms and are asymptomatic. Large worm burdens and symptomatic disease affect a relatively small proportion of those who are infected.

While some helminths such as Enterobius vermicularis and Toxocara canis are found worldwide, others are more geographically restricted (eTable 207-1.1). Most infections occur in developing tropical or subtropical countries, where environmental conditions are conducive to the completion of the life cycle of many helminths, and the requisite animal hosts and vectors for ongoing transmission exist. In addition, the high population density, poverty, and poor sanitation commonly found in these areas further facilitate the transmission of these diseases. Knowledge of the geographic distribution of specific helminths is important for the clinician, and will help to direct appropriate investigations and management.

Species | North America | Central America | South America | Caribbean | Europe | North Africa/Middle East | Sub-Saharan/South Africa | South Central Asia (Incl. Indian Subcontinent) | East/Southeast Asia | Australia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nematodes (Roundworms) | ||||||||||

Ancylostoma braziliense | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus (hookworm) | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Ascaris lumbricoides | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Dirofilaria spp. (repens, immitis) | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Dracunculus medinensis | ++ | |||||||||

Enterobius vermicularis | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

Filariae | ||||||||||

Brugia malayi | ++ | ++ | ||||||||

Brugia timori | ++ | |||||||||

Loa loa | ++ | |||||||||

Mansonella ozzardi | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||

Mansonella perstans | ++ | ++ | ||||||||

Mansonella streptocerca | ++ | |||||||||

Onchocerca volvulus | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||||||

Wuchereria bancrofti | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||

Gnathostoma spinigerum, others | ++ | ++ | ||||||||

Strongyloides stercoralis | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||

Toxocara cani, Toxocara cati | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

Trichinella spiralis | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + |

Trematodes (Flukes) | ||||||||||

Clonorchis sinensis | ++ | ++ | ||||||||

Fasciola hepatica | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||||

Fasciolopsis buski | ++ | ++ | ||||||||

Heterophyes heterophyes | ++ | ++ | ||||||||

Metagonimus yokogawi | ++ | |||||||||

Paragonimus westermani | + | + | ++ | |||||||

Schistosoma | ||||||||||

Schistosoma hematobium | ++ | ++ | ||||||||

Schistosoma japonicum | ++ | |||||||||

Schistosoma mansoni | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||||||

Schistosomes, avian (swimmer’s itch) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

Cestodes (Tapeworms) | ||||||||||

Diphyllobothrium latum | ++ | + | ++ | + | ||||||

Echinococcus granulosus | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

Echinococcus multilocularis | ++ | ++ | ||||||||

Hymenolepis nana | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

Spirometra mansonoides, others (sparganosis) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + |

Taenia multiceps, others (coenurosis) | + | + | + | ++ | ||||||

Taenia saginata | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

Taenia solium (cysticercosis) | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

Helminthic infections are less prevalent in temperate and northern climates, although some diseases are endemic even in these regions (eTable 207-1.1). In developed countries and colder climates, helminthic diseases are more often imported by travelers to or immigrants from endemic areas. Less frequently, helminthic infections in developed nations can be locally acquired (e.g., trichinellosis resulting from improperly prepared food) or transmitted via person-to-person spread (e.g., enterobiasis).

Dermatologic disorders are the third most common illness in travelers.1 In several observational studies, 5%–17% of travelers to varied destinations developed a dermatologic condition during or after travel.2–6 These figures cannot necessarily be generalized to all travelers; however, as the studies included travelers assessed only in specialty (travel and tropical medicine) clinics, and may also have been subject to geographic biases (due to the specific population of travelers studied and/or the more common travel destinations among these travelers).

Infections, including tropical skin diseases, are common causes of dermatoses among travelers. Insect bites, allergic reactions, and other rashes are among the most prevalent noninfectious dermatologic diagnoses in travelers. Of the helminthic skin infections, cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is by far the most commonly reported in travelers and accounts for 5%–25% of all skin diseases in this group.6–8 Most other helminthic infections that may be associated with dermatologic findings are relatively rare in travelers.

The prevalence of dermatologic conditions in immigrants and refugees has not been exhaustively studied. Two studies suggest that skin conditions among these populations occur no more frequently3 or, in one study, much less commonly5 than in travelers; however, these studies are subject to the same biases noted above.

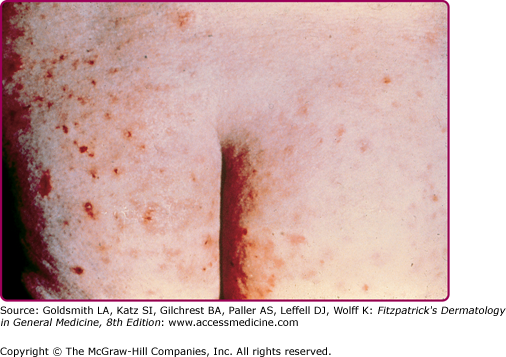

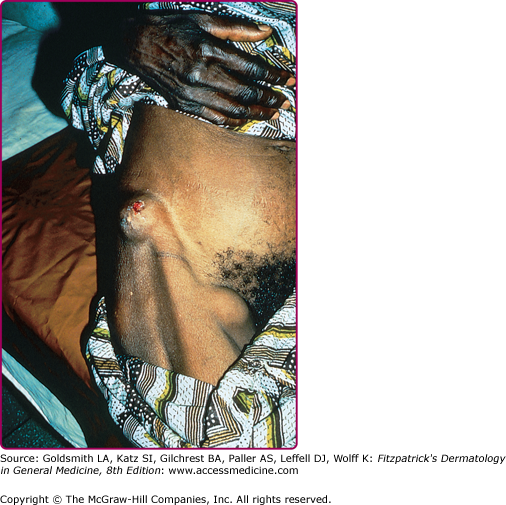

The helminths that cause skin findings in this population, and the clinical presentation, may also differ from those in travelers. For example, filarial infections are more commonly encountered in individuals who have resided in endemic areas for prolonged periods rather than in travelers,8 since they usually require repeated exposures to insect vectors in order for effective transmission to occur. Strongyloidiasis is also more prevalent in immigrants from endemic areas, particularly Southeast Asia, and often presents with eosinophilia or nonspecific abdominal symptoms.9 Acute onchocerciasis may occur in short-term (at least 1 month) visitors to endemic areas and characteristically presents with a hyperimmune response manifest by pruritus and rash (Fig. 207-1),10,11 in spite of low-parasite loads. In contrast, infected immigrants more commonly have chronic onchodermatitis, chronic skin changes including atrophy, hypopigmentation and lichenification, and onchocercal nodules (Fig. 207-2).

All helminths have complex life cycles that include maturation from eggs (or other infective forms) to larvae (or other immature forms) to adults. Human disease results from ingestion of eggs or other infective forms or, alternatively, exposure of the skin to infective forms (larvae or cercariae) by direct contact or via the bite of an insect vector. Humans may be the primary hosts for some helminths (e.g., Strongyloides stercoralis), or may be incidental or accidental hosts (e.g., avian schistosomes, animal hookworm, and T. canis). Helminths that are well adapted to humans can mature from the infective stage into adult forms in the human host; infection generally persists for the lifespan of the adult worm, which in some cases can be for many years. In contrast, animal helminths cannot mature into adult forms in humans (who in this setting are therefore “dead-end” hosts), although infection can still cause tissue damage and clinical findings.

In general, helminths do not multiply in the human host. Most helminths (with the notable exception of S. stercoralis) are incapable of completing an entire life cycle in the human host, and depend on the environment (e.g., soil, water), plants, or other animal hosts or insects, for their survival. Consequently, transmission of infection requires the presence of appropriate environmental conditions, specific intermediate hosts (in whom only the asexual reproductive cycle occurs) and/or specific insect vectors, explaining in large part the localized geographic distributions of many helminthic diseases.

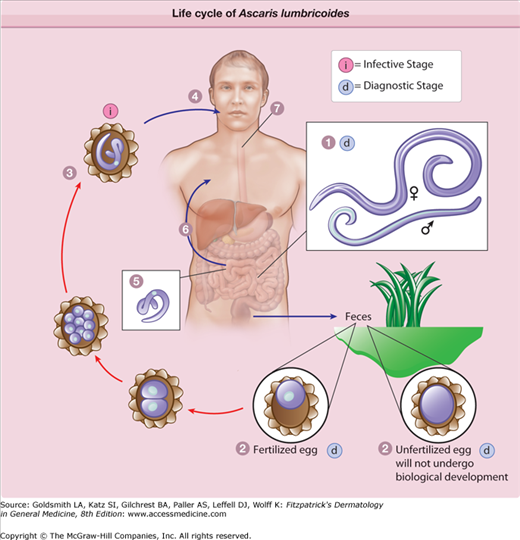

Examples of helminthic diseases acquired by ingestion of infective forms (eggs or metacercariae) in contaminated food or water include Ascaris lumbricoides and Fasciola hepatica. In ascariasis (eFig. 207-2.1), swallowed eggs are consumed, larvae are released within the gastrointestinal tract, and migrate through the portal-systemic circulation to the lungs, from where they are swallowed. Skin disease such as urticaria may occur during the larval migration phase. Once in the gastrointestinal tract, larvae mature into adult worms where sexual reproduction may take place; either eggs or adult worms can be shed in stool. Eggs must mature in soil before releasing infective larvae. In fascioliasis, infective metacercariae excyst in the small intestine and migrate through the intestinal wall and peritoneum to their target tissue, the biliary tract, where they become adults. Again, skin findings typically occur as immature forms migrate. Eggs produced by adult flukes are passed in feces and become infective for humans only after maturation in a suitable (intermediate) snail host.

eFigure 207-2.1

The life cycle of Ascaris lumbricoides. Adult worms (1) live in the lumen of the small intestine. A female may produce approximately 200,000 eggs/day, which are passed with the feces (2). Unfertilized eggs may be ingested but are not infective. Fertile eggs embryonate and become infective after 18 days to several weeks (3), depending on the environmental conditions. After infective eggs are swallowed (4), the larvae hatch (5), invade the intestinal mucosa, and are carried via the portal, then systemic circulation to the lungs (6). The larvae mature further in the lungs (10–14 days), penetrate the alveolar walls, ascend the bronchial tree to the throat, and are swallowed (7). Upon reaching the small intestine, they develop into adult worms (1). Between 2 and 3 months are required from ingestion of the infective eggs to oviposition by the adult female. Adult worms can live 1–2 years. (Redrawn from http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Ascariasis.htm.)

Schistosomiasis results from penetration of intact skin by infective cercariae (eFig. 207-2.2). Dermatologic findings in early disease manifest either at the time of cercarial penetration (swimmer’s itch or cercarial dermatitis), or during migration of immature forms (schistosomulae) from the skin and through tissue to the venous systems of their target organs (which may vary depending on the infecting species), where they mature into adults. Migration of schistosomulae in previously unsensitized individuals (usually travelers) can result in acute illness (Katayama fever) consisting of fever, myalgias, cough, and wheezing, and may be accompanied by urticaria. Sexual reproduction leads to the release of eggs into the local circulation. En route to the bladder or bowel, eggs may sometimes become trapped in ectopic tissues, including skin, where they cause a granulomatous reaction. In skin, this may lead to a chronic papular eruption. Eggs excreted in urine or feces hatch in fresh water, releasing cercariae, which must undergo further maturation in one of several intermediate snail hosts in order to infect humans.

eFigure 207-2.2

The life cycle of Schistosoma species. Eggs are eliminated with feces or urine (1). Under optimal conditions the eggs hatch and release miracidia (2), which swim and penetrate specific snail intermediate hosts (3). The stages in the snail include two generations of sporocysts (4) and the production of cercariae (5). Upon release from the snail, the infective cercariae swim, penetrate the skin of the human host (6), and shed their forked tail, becoming schistosomulae (7). The schistosomulae migrate through several tissues and stages to their residence in the veins (8 and 9). Adult worms in humans reside in the mesenteric venules in various locations, which at times seem to be specific for each species (10). For instance, Schistosoma japonicum is more frequently found in the superior mesenteric veins draining the small intestine (a), and Schistosoma mansoni occurs more often in the superior mesenteric veins draining the large intestine (b). However, both species can occupy either location, and they are capable of moving between sites, so it is not possible to state unequivocally that one species only occurs in one location. Schistosoma haematobium most often occurs in the venous plexus of bladder (c), but it can also be found in the rectal venules. The females (size 7–20 mm; males slightly smaller) deposit eggs in the small venules of the portal and perivesical systems. The eggs are moved progressively toward the lumen of the intestine (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) and of the bladder and ureters (S. haematobium), and are eliminated with feces or urine, respectively (Redrawn from http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Schistosomiasis.htm).

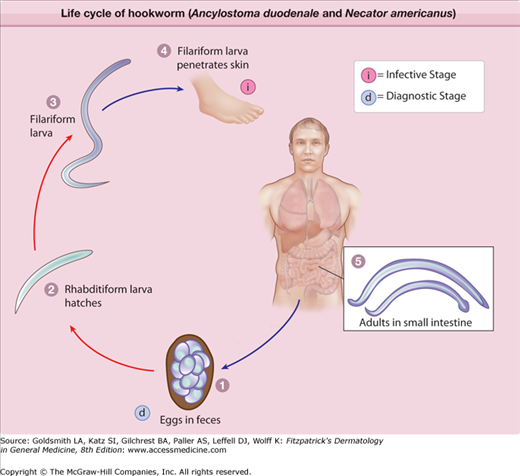

Infection can also result from penetration of intact skin by larvae, exemplified by human hookworm infection (eFig. 207-2.3). Larval skin penetration may cause localized papular or vesicular lesions, or creeping eruption. Larvae then migrate to the circulatory system where they are carried to the lungs, penetrate the alveoli, and ascend the bronchial tree, are swallowed, and enter the gastrointestinal tract. Skin findings may also occur during larval migration to the lungs. Maturation into adult worms occurs in the small intestine, where they reproduce and release eggs into stool. Under the appropriate environmental conditions, eggs mature into infective larvae in soil. In contrast, larvae of animal hookworms (e.g., Ancylostoma braziliense) cannot mature beyond the larval stage in humans and tunnel aimlessly in the skin before the infection eventually extinguishes itself.

eFigure 207-2.3

The life cycle of hookworm (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus). Eggs are passed in the stool (1), and under favorable conditions (moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch in 1–2 days. The released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces and/or the soil (2), and after 5–10 days (and two molts) they become filariform (third-stage) larvae that are infective (3). These infective larvae can survive 3–4 weeks in favorable environmental conditions. On contact with the human host, the larvae penetrate the skin and are carried through the blood vessels to the heart and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed (4). The larvae reach the small intestine, where they reside and mature into adults. Adult worms live in the lumen of the small intestine, where they attach to the intestinal wall with resultant blood loss by the host (5). Most adult worms are eliminated in 1–2 years, but the longevity may reach several years. Some A. duodenale larvae, following penetration of the host skin, can become dormant (in the intestine or muscle). In addition, infection by A. duodenale may probably also occur by the oral and transmammary route. N. americanus, however, requires a transpulmonary migration phase. (Redrawn from http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Hookworm.htm.)

Larvae can also be introduced through intact skin by insect bites (e.g., in filarial infections). The insect vector and the target tissue both vary according to the infecting species; cutaneous disease may be seen during either migration of larval forms through tissue, or as a result of adult worms in tissue. Microfilariae released from mature adult worms are taken up by an insect during a subsequent blood meal, and then undergo maturation to infective forms within the insect before being introduced into another human host.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

A variety of helminths can infect humans and cause cutaneous findings (Table 207-2). Cutaneous manifestations can be seen at every phase of the helminth life cycle in humans: by larvae or cercariae during skin penetration; during larval migration and tissue invasion; and due to the presence of eggs and adult worms in skin and soft tissues. Skin lesions also may occur during either early (acute) or chronic infection.

Species | Localized Edema | Migratory Skin Lesions | Nodules or Masses | Papules | Petechiae | Pruritus | Urticaria | Ulcer | Vesicle/Bulla |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nematodes (Roundworms) | |||||||||

Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma caninum | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus (human hookworm) | X | X | X | X | |||||

Ascaris lumbricoides | X | X | |||||||

Dirofilaria spp. | Rare | X | |||||||

Dracunculus medinensis | Xa | X | X | X | |||||

Enterobius vermicularis | X | ||||||||

Filariae | |||||||||

Brugia spp. (malayi, timori) | Xb | X | |||||||

Loa loa | Xa | X | X | X | X | ||||

Mansonella spp. (ozzardi, perstans, streptocerca) | Xb | X | X | ||||||

Onchocerca volvulus | Rarea | X | X | X | X | X | |||

Wuchereria bancrofti | Xb | X | |||||||

Gnathostoma spinigerum, others | Xa | X | X | X | X | ||||

Strongyloides stercoralis | X | X | Xc | X | X | ||||

Toxocara spp. (canis, cati) | X | X | |||||||

Trichinella spiralis | Xa | X | X | X | X | ||||

Trematodes (Flukes) | |||||||||

Fasciola hepatica | X | X | X | ||||||

Paragonimus westermani | X | X | X | X | |||||

Schistosoma spp. (human and avian) | X | X | X | X | |||||

Cestodes (Tapeworms) | |||||||||

Echinococcus spp. (granulosis, multilocularis) | X | ||||||||

Spirometra mansonoides, others (sparganosis) | X | X | |||||||

Taenia multiceps, others (coenurosis) | X | ||||||||

Taenia solium (cysticercosis) | X |

The pathogenesis of skin lesions in helminthic infections is varied. Direct penetration of skin may lead to a localized immune response, as seen in CLM or cercarial dermatitis. Migration of helminths can cause a generalized immune response (urticaria; maculopapular eruptions), particularly due to migration of larvae or immature forms (e.g., with Ascaris or Toxocara infection); a local inflammatory reaction to adult worms or eggs may also develop, as occurs with cutaneous nodules due to Onchocerca volvulus and in schistosomiasis. Skin changes can also result from disruption of the normal skin structures due to lymphedema, as with filarial infections. Finally, ill-defined systemic immune reactions such as erythema nodosum (EN) or erythema marginatum, rarely reported manifestations of several helminthic infections, may also be present. Skin findings of helminthic infections do not generally result from hematogenous spread of parasites, in contrast to many bacterial and viral infections.

Helminths induce a dramatic expansion of the T helper 2 (Th2) lymphocyte subset, with elevated levels of immunoglobulin E (IgE), peripheral eosinophilia, and an increase in tissue mast cells. It is unclear whether these Th2-derived responses are important in the protective immune response against the parasite, are responsible for immune-mediated pathology, or both.12 Despite high levels of IgE and other features of Th2 cell activation, allergic responses are rarely observed in infected individuals except during the invasive phase of infection, when pruritus and/or urticaria may occur. Infected hosts have evolved elaborate immune evasion strategies that permit long-lived helminthic infections, including the induction of tolerance to parasite antigens.

Approach to the Patient

With the exception of CLM, most travelers and immigrants who present with dermatologic complaints will not have a diagnosis attributable to a helminthic infection. However, clearly these must be considered if the epidemiologic and exposure history and clinical findings are consistent with a helminthic infection, since these are treatable infections that have important clinical implications, such as disseminated strongyloidiasis in an immunocompromised host.

As with all diseases of travelers and immigrants, a thorough history is essential in order to direct the clinician toward the correct diagnosis. The history should focus on aspects related to travel (or residence in endemic areas), general medical conditions, and medications. In addition, specific details of the dermatologic complaints must also be obtained. Finally, the clinician should be knowledgeable about (or know how to find out about) outbreaks of disease that may have been ongoing during an individual’s travel or residence in a given area.

The travel history (or history of residence in endemic areas) must be thorough in order to elucidate likely exposures to helminths. Specific details may be more readily obtained in recently returned travelers than immigrants, although immigrants are much more likely to be aware of local and endemic diseases (albeit often by local names). Details to be obtained include the exact dates, durations, and locations of travel or residence; purpose of travel; activities or occupations, inquiring specifically about those that would increase exposure to specific helminths (Table 207-3); dietary intake; a history of similar signs and symptoms in other family members or fellow travelers; and the use of preventive measures.

Exposure or Activity | Disease/Syndrome | Comments |

|---|---|---|

Barefoot walking or walking in open shoes (sandals) | Cutaneous larva migrans Human hookworm (Ancylostoma duodenalis, Necator americanus) Strongyloidiasis | |

Swimming or water exposure | Schistosomiasis (human) Cercarial dermatitis (schistosomiasis, avian) | Freshwater exposure in Africa, Arabian peninsula (Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma hematobium); or South America (S. mansoni) Freshwater or saltwater exposure |

Dietary indiscretion Contaminated food or water (also via contaminated fingers) Contaminated water Raw or undercooked meat Raw or undercooked seafood, crustaceans, amphibians, reptiles Contaminated plants | Ascariasis Enterobiasis (pinworm) Toxocariasis Dracunculiasis Sparganosis Cysticercosis (Taenia solium) Sparganosis Trichinellosis Gnathostomiasis Paragonimiasis Sparganosis Fascioliasis | Infected pork Infected rodent meat Infected meat (mainly pork, but other wild and domestic meats) Watercress |

Insect bitesa Mosquito Fly | Dirofilariasis Lymphatic filariasis (Brugia spp., Wuchereria bancrofti) Filariasis (Mansonella spp.) Loiasis Onchocerciasis | Use of personal protective measures (insect repellent, bed nets) can be protective |

Other Topical poultices | Sparganosis | Poultices containing infected amphibian, reptile, or rodent meats |

The exact destinations of travel (urban vs. rural), not only the country or countries visited, are important to obtain. Although some diseases may be endemic throughout a world region or area (eTable 207-1.1), the prevalence of others may vary greatly, sometimes within a given country. For example, onchocerciasis and loiasis are endemic in West Africa, but generally not in other parts of Africa, and both infections are found only in rural areas, unlike Bancroftian filariasis (Wuchereria bancrofti) that is often transmitted in urban centers. The risk of disease may not be present in all areas of a country in which a disease is considered to be endemic; for example, schistosomiasis is found in Brazil, but only in the northeastern region. Duration of travel or residence in an endemic area (and hence duration of exposure) is relevant for some diseases; schistosomiasis can be acquired after a single exposure to infective cercariae in freshwater, whereas filariasis is often acquired only after numerous bites, and therefore is rare among short-term travelers to endemic areas.

The purpose of travel is also correlated with the likelihood of exposure to specific pathogens. Rural and adventure travelers are more likely to be exposed to helminthic infections than are business travelers, travelers whose itineraries are limited to urban areas, and those whose travels are of shorter durations.

Certain activities and occupations will place individuals at greater risks of helminthic infections while abroad (Table 207-3). Examples of common exposures and associated diseases include barefoot walking or walking in open shoes (sandals) (e.g., CLM, strongyloidiasis); freshwater swimming in Africa (e.g., schistosomiasis); and dietary indiscretions such as consumption of salads or undercooked or contaminated meat or fish (e.g., ascariasis, echinococcosis, fascioliasis, gnathostomiasis). Although direct exposure to animals is not a risk factor for helminthic infections, the risk of CLM is greater in areas with a higher prevalence of stray dogs and cats. For those infections that are vector borne, such as filarial infections transmitted by mosquitoes, black flies, and deer flies, the use of preventive measures such as appropriate clothing, insect repellent, and bed nets can reduce the risk of infection.

In addition to the travel history, a general medical history should be obtained. Skin findings may be related to underlying medical conditions, or to any associated treatment for these. The differential diagnosis of skin lesions in a returned traveler or immigrant also includes noninfectious disorders such as contact dermatitis (including to jewelry), drug eruptions, and photosensitivity reactions (that may be precipitated by travel-related medications such as doxycycline). A list of prescription and nonprescription medications or supplements should be obtained, in particular those that may have been started recently and/or prescribed abroad, as well as any recent use of topical medications or products.

The dermatologic history should include details regarding the initial presentation, morphology, and anatomic distribution of skin lesions; the progression and duration of lesions; time of onset relative to potential exposures; and any associated local and systemic signs and symptoms. Although some manifestations of helminthic infections, such as urticaria or maculopapular eruptions, are nonspecific, the differential diagnosis of helminthic dermatoses can often be narrowed based on the description and morphology of the lesion(s) present. For some diseases such as CLM, skin findings are virtually pathognomonic and the diagnosis can be established by history and careful examination of skin lesions, often without the need for additional investigations.

Skin lesions due to helminthic infections can assume a variety of morphologies. The most commonly encountered problem is that of migratory skin lesions. CLM (creeping eruption) is the most common cause of migratory lesions in general. Subcutaneous nodules, papular eruptions, and urticaria and pruritus are also common manifestations of helminthic infections.

Migratory lesions can be caused by multiple helminths. Migratory lesions can be linear (serpiginous) or may be more ill-defined areas of erythema and swelling, and may be painless, painful, or pruritic. Table 207-4 lists the most common helminthic causes of migratory lesions, as well as characteristic features of these lesions.

Helminth | Morphology of Lesion | Description | Most Common Location |

|---|---|---|---|

Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma caninum | Serpiginous (CLM) | Typically one to three serpiginous lesions, 3 mm wide and up to 20 cm in length; intensely pruritic, may be vesicobullous; movement up to several cm per day | Feet, buttocks |

Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus (human hookworm) | Serpiginous | Pruritic tracks due to larval migration | Feet |

Dracunculus medinensis | Localized area of edema or swelling with movement beneath | Moving mass may be seen just before emergence of adult worm through skin | Feet |

Fasciola hepatica | Migratory subcutaneous swellings | Erythematous, painful, pruritic subcutaneous nodules may have a migratory component; larval track marks may also be seen | Abdomen, back, extremities |

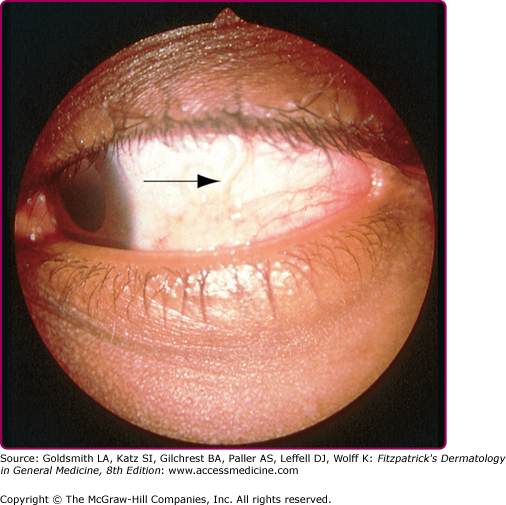

Loa loa | Migratory subcutaneous swelling or serpiginous | Migration of adult worm across conjunctivae or under skin | Skin, eye |

Gnathostoma spinigerum | Serpiginous (CLM) | Migration of larvae can cause creeping eruption; movement 1 cm/hour | Trunk, upper body |

Migratory subcutaneous swellings (eosinophilic panniculitis) | Intermittent single or multiple erythematous swellings; may be migratory, pruritic or painful; last 1–4 weeks, with recurrences in different anatomic areas after variable asymptomatic periods | Thighs | |

Paragonimus westermani | Migratory subcutaneous swellings or nodules | Firm migratory swellings or nodules, may be migratory; slightly tender and slightly mobile, up to 6 cm diameter; swellings contain immature flukes | Lower abdomen, inguinal region |

Spirometra mansonoides, others (sparganosis) | Migratory subcutaneous swellings | Slow-growing, typically painful swellings that may be migratory; may be pruritic | Abdomen, lower extremities |

Strongyloides stercoralis (larva currens) | Serpiginous (larva currens) | Movement at 5–10 cm/hour; intensely pruritic, transient, but recurrent | Buttocks, groin, trunk, thighs |

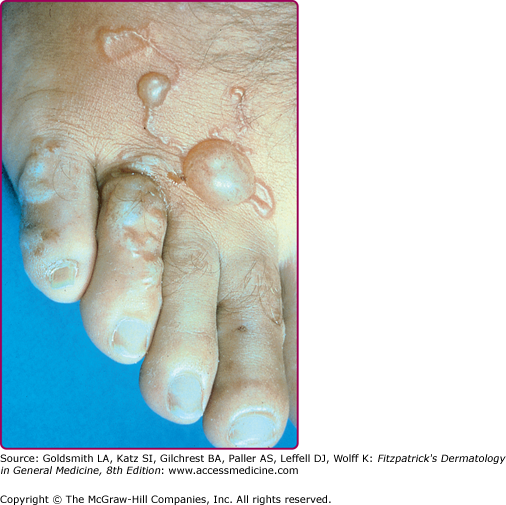

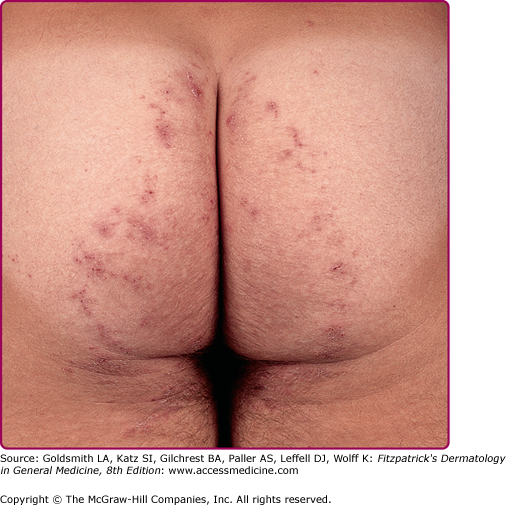

Serpiginous and linear lesions are most commonly due to CLM (most frequently caused by A. braziliense and Ancylostoma caninum; see also Section “Hookworm-Related Cutaneous Larva Migrans”). Usually one to three (or more) erythematous, serpiginous, and intensely pruritic lesions due to intradermal larval migration are present (Fig. 207-3); bullae and vesicles may also be present (Fig. 207-4). Lesions usually measure 3 mm in width and 15–20 cm in length. Lesions of CLM may rarely be accompanied by severe folliculitis, or may present as papules alone without a linear element (papular larva migrans). Serpiginous skin lesions in S. stercoralis infection, a pathognomonic manifestation of strongyloidiasis known as larva currens, typically present as recurrent, transient, and rapidly moving skin lesions (Fig. 207-5). Larval migration may occur at rates of 5–10 cm/hour, and the lesions usually disappear within hours only to recur over subsequent weeks to years. Lesions typically occur on the buttocks and in the perianal region, as larvae exit the gastrointestinal tract and reinfect the host by penetrating the perianal skin. Linear migratory lesions can also be seen occasionally in human hookworm infection (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus) at the site of larval penetration, and in gnathostomiasis (usually relatively slow migration at 1 cm/hour). Linear migratory lesions can also be seen in Loa loa infection, and result from movement of the adult worm (not larvae) in tissue, typically under the skin or also across the bulbar conjunctivae (Fig. 207-6).

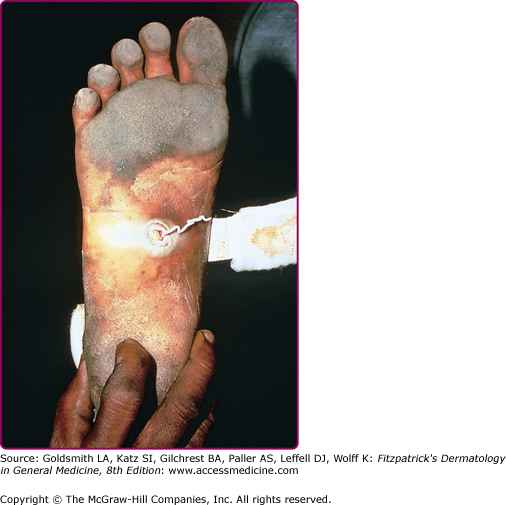

Migratory subcutaneous swellings and nodules are characteristic of infections due to Fasciola, Gnathostoma, and Paragonimus, and in sparganosis (Spirometra species). Lesions may be painful or pruritic. Migratory swelling due to the movement of adult worms is also seen in dracunculiasis, in which movement within a bullous, vesicular, or edematous lesion on the foot is often noted prior to eruption of the skin lesion and egress of the adult worm (Fig. 207-7). Since the implementation of global eradication and drinking water monitoring programs in endemic countries, cases of dracunculiasis have decreased dramatically and the disease has almost been eliminated.13

Subcutaneous and soft tissue masses may have variable characteristics, including overlying erythema, pain or tenderness, and pruritus. They may be single or multiple, and fixed or mobile. The more common etiologies of nodular lesions are listed in Table 207-5.

Helminth | Description of Nodular Lesion | Most Common Location |

|---|---|---|

Brugia malayi | Hydrocele/scrotal mass due to lymphatic obstruction. | Scrotum |

Dirofilaria spp. | Single erythematous, well-defined firm nodule or mass, usually 1–5 cm diameter; usually asymptomatic but may be tender; rarely may be migratory (usually not). | Head and neck, breasts, extremities, scrotum |

Dracunculus medinensis | Edematous lesion/mass may be seen just before emergence of adult worm through skin; movement underneath lesion due to movement of adult worm | Feet |

Echinococcus spp. | Firm subcutaneous (or muscular) nodules or masses; usually single but may be multiple; may feel fluctuant; nontender. Rarely with fistulization and inflammation of skin (Echinococcus multilocularis). True cutaneous lesions are rare. | Abdomen |

Gnathostoma spinigerum | Intermittent single or multiple erythematous swellings; may be migratory, pruritic or painful; last 1–4 weeks, with recurrences in different anatomic areas after variable asymptomatic periods. | Trunk, upper body, thighs |

Loa loa | Calabar swelling—localized angioedema, 5–20 cm diameter, usually lasting 2–4 days but recurrent; due to migration of adult worms. | Eyelid, upper extremities, periarticular regions (especially knee, wrist) |

Mansonella perstans | Calabar swellings—localized swellings lasting 1–4 days, recurrent. | Face, upper extremities (especially forearms), hands |

Onchocerca volvulus | Well-defined, fixed painless nodules containing adult worms in deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. | Over bony prominences including skull (South America), ribs, iliac crest (Africa), others |

Paragonimus westermani | Firm swellings or nodules, may be migratory; slightly tender and slightly mobile, up to 6 cm diameter; swellings contain immature flukes. | Lower abdomen, inguinal region |

Spirometra mansonoides, others (sparganosis) | Slow-growing, typically painful swellings that may be migratory; may be pruritic. | Abdomen, lower extremities |

Taenia multiceps, others (coenurosis) | Solitary subcutaneous (or muscular) nodule, usually 2–6 cm diameter; painless | Trunk (especially intercostal regions), anterior abdominal wall; head, neck, extremities less commonly |

Taenia solium (cysticercosis) | Painless, fixed, well-circumscribed rubbery subcutaneous nodules in 50% of patients with cysticercosis; may be single or multiple; average size 2 cm in diameter. | Trunk, extremities |

Wuchereria bancrofti | Hydrocele/scrotal mass due to lymphatic obstruction. | Scrotum |

Solitary nodules or masses are found in echinococcosis, filariasis due to Brugia malayi and W. bancrofti (both of which may cause scrotal masses in men, due to lymphatic obstruction), dirofilariasis, and coenurosis. Multiple nodules are typical of cysticercosis (Taenia solium infection), in which small, painless subcutaneous or intramuscular nodules are present, although single nodules can also occur. Subcutaneous cysticercosis, although reported in over 50% of infected individuals in older case series,14 currently occurs in less than 10% of cases. Most other helminths that manifest as subcutaneous nodules or masses may present with single or multiple lesions. Painless nodules are most characteristic of coenurosis, cysticercosis, dirofilariasis, echinococcosis, and onchocerciasis. Painful nodules are seen in paragonimiasis and sparganosis. Transient painful lesions that resolve and subsequently recur in different anatomic areas are characteristic of Gnathostoma infection and loiasis. Fixed lesions are typical of cysticercosis, echinococcosis, and onchocerciasis.

Papules and macules occur in relatively few helminthic infections (Table 207-6). Papular lesions may occur at sites of skin penetration by infective larvae or cercariae in CLM and schistosomiasis. In CLM, papules are typically in the feet or buttocks, similar to the distribution of migratory lesions. In schistosomiasis, exposure to infected freshwater (for avian or human schistosomes) or salt water (avian schistosomes) may cause pruritus, which is followed rapidly by a papular eruption in previously sensitized individuals. Chronic papular lesions (bilharziasis cutanea tarda) may be present in chronic schistosomiasis. Papular lesions may also be manifestations of acute or chronic infection with O. volvulus, and have been reported in disseminated and chronic strongyloidiasis.

Helminth | Description | Most Common Location |

|---|---|---|

Ancylostoma braziliense, caninum (CLM) | Pruritic erythematous papule(s) within days of larval penetration; may be vesicular; also papular larva migrans. | Feet, buttocks |

Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus (human hookworm) | Ground itch: in sensitized individuals, pruritic papular lesions at sites of larval entry; may be vesicular. | Feet, hands |

Mansonella perstans, streptocerca | Multiple pruritic papules; hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules and lichenification may be present. | Upper chest (M. streptocerca) |

Onchocerca volvulus | Acute: multiple pruritic papules, may become vesicular or pustular; may be erythematous and edema may be present. | Face, trunk, extremities |

Chronic: intensely pruritic, flat papules (3–9 mm) or macules, may be hyperpigmented or lichenified. | Shoulders, buttocks, waist, extremities | |

Schistosoma species (avian) | Erythematous papular or maculopapular lesions, may be vesicular or urticarial; intensely premitotic; onset within 24 hours of saltwater or freshwater exposure, lasts 1–3 weeks. | Any surface exposed to water |

Schistosoma species (human) | Acute: erythematous papular and urticarial lesions in previously sensitized individuals; onset within hours of freshwater exposure, lasting 1 week. | Any surface exposed to water |

Chronic: bilharziasis cutanea tarda; slightly pigmented 2–4 mm firm, pruritic, oval papules or papulonodular lesions, may be verrucous or polypoid; may appear in crops; due to granulomatous reaction to eggs in skin. | Trunk, especially periumbilical region; buttocks, genitalia |

Pruritus (Table 207-7) may be present in the absence of skin findings, either as a primary symptom of infection (e.g., filariasis due to Mansonella perstans), or before the onset of skin lesions (e.g., schistosomiasis). Pruritus is a common feature of most helminthic infections, with the noteworthy exceptions of lymphatic filariasis (e.g., due to Brugia species and W. bancrofti) and tapeworm infections. Pruritus ani

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree