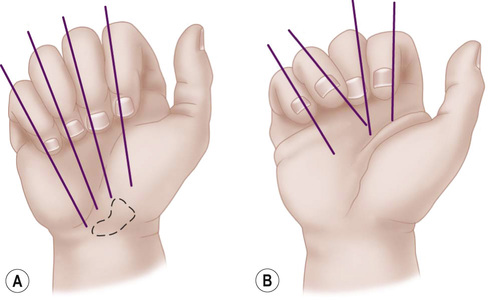

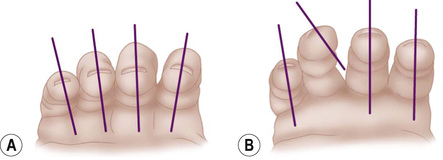

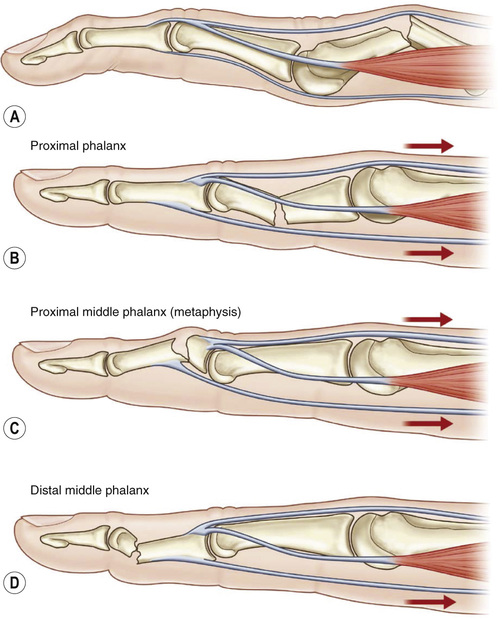

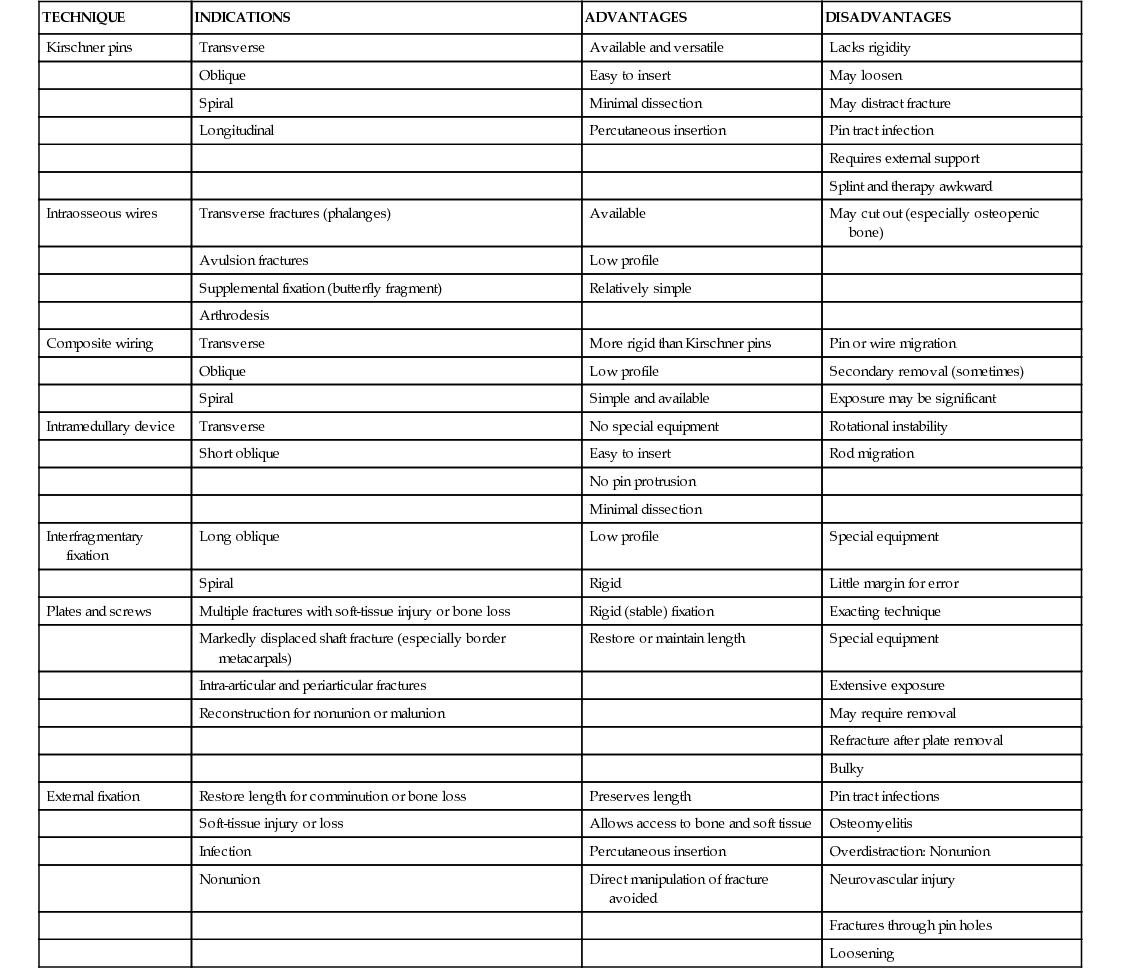

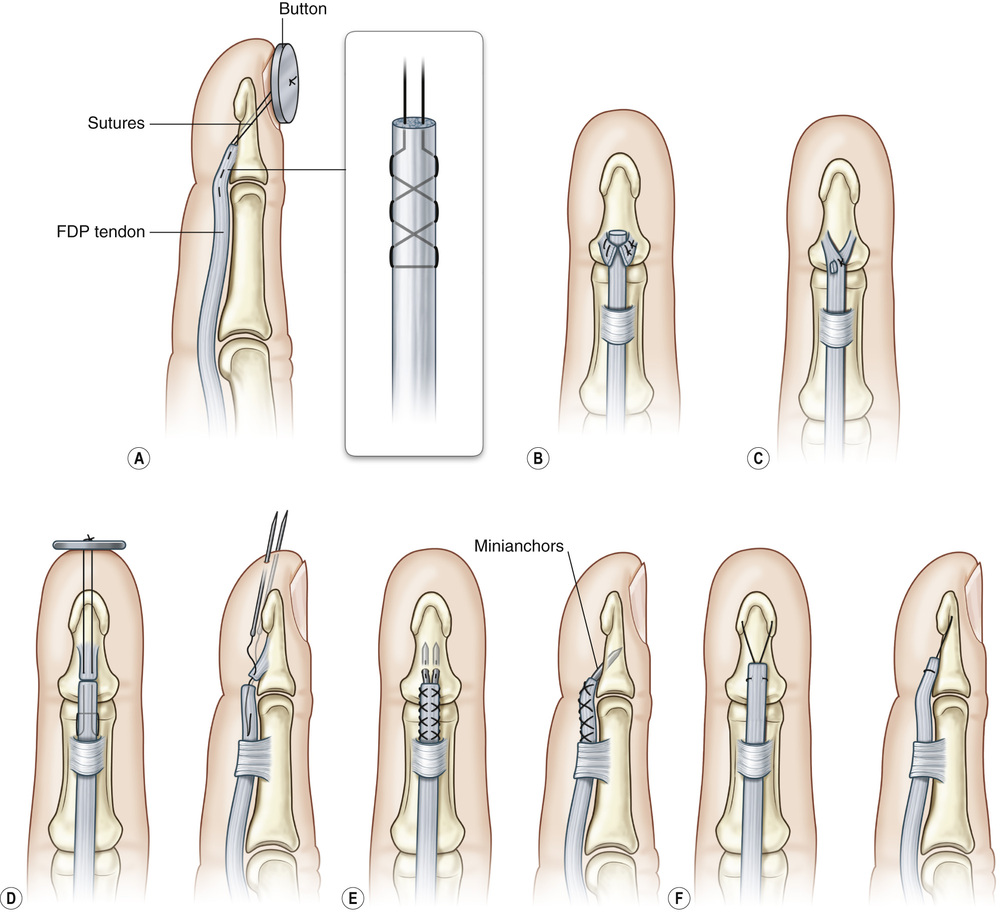

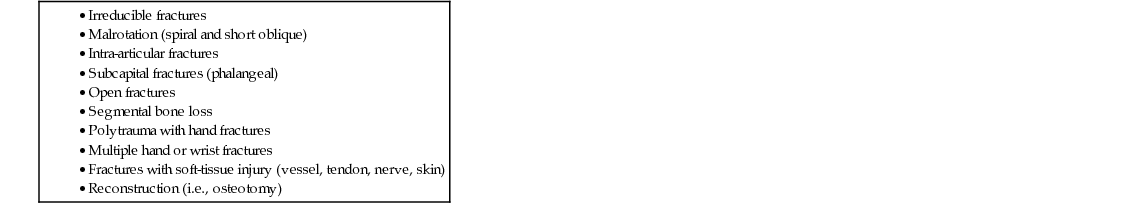

1. Metacarpal and phalangeal fractures are the most common fractures in the upper extremity. 2. Diagnosis requires a thorough history, physical examination, and radiographic images. • Specifically, look for open lacerations, digital shortening, malrotation (see Figures 16.1 and 16.2), scissoring, gross deformity, and angulation (see Figure 16.3), which affects hand motion/function. 4. General indications for fixation of these fractures are shown in Table 16.1 Table 16.1 Indications for Fixation of Metacarpal and Phalangeal Fractures 5. Numerous fixation techniques are available, although many fractures can be adequately fixed with percutaneous pinning (see Table 16.2). 1. Mallet finger (see Figure 16.4): Disruption, either tendinous or bony, of the terminal extensor tendon at or distal to the distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) • Etiology: Forced flexion of the DIPJ due to an impaction force to tip of extended finger ▪ Extension splinting of the DIPJ for 6 to 8 weeks; keep proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint free ▪ Operative repair is indicated with volar subluxation, >50% articular surface involvement, and/or >2 mm articular gap. Can be performed with ○ Open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) ▪ Terminal tendon reconstruction in chronic injuries (>12 weeks) ▪ DIP arthrodesis is reserved for treatment of chronically painful, arthritic DIP joints. 2. Jersey finger: Avulsion of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon from its insertion at the base of the distal phalanx • Etiology: Forced DIPJ extension of an actively flexed DIPJ (i.e., athlete grasping a moving object such as a jersey, etc.) • Leddy-Packer classification (see Table 16.3) ▪ Based on the level of tendon retraction and presence of fracture Table 16.3 Leddy-Packer Classification of Flexor Digitorum Profundus Avulsion Injury (Jersey Finger) ▪ Types I, II: Direct tendon repair or tendon reinsertion with a dorsal button ○ Indications: Acute injuries (<4 weeks) ▪ Types III, IV: ORIF of the fracture fragment with a K wire, screw, or pull-out wire

Hand Fractures and Dislocations

General Treatment of Metacarpal and Phalangeal Fractures

Distal Phalanx Injuries

LEDDY-PACKER TYPE

DESCRIPTION

TREATMENT

Type I

FDP tendon retracted to palm. Leads to disruption of the vascular supply

Prompt surgical treatment within 10 to 14 days to avoid need for tendon graft

Type II

FDP retracts to level of PIP joint (caught on A3 pulley)

Can repair within 3 months without need for tendon graft; however, over time can convert to type-1 injury

Type III

Large avulsion fracture limits retraction to the level of the DIP joint (caught on A4 pulley)

Can often be repaired at any time without need for tendon graft, even if after 3 months

Type IV

Osseous fragment and simultaneous avulsion of the tendon from the fracture fragment (retraction of the tendon into palm)

If tendon separated from fracture fragment, first fix fracture via ORIF, then reattach tendon as for type-I and -II injuries

Hand Fractures and Dislocations

Chapter 16