Granuloma Inguinale: Introduction

|

Epidemiology and Mode of Transmission

The mode of transmission of granuloma inguinale (GI) is controversial. It is generally considered sexually transmitted, but fecal contamination and autoinoculation remain a possibility, especially in the setting of infected children and adults without sexual activity and primary involvement of remote extragenital sites.1,2 Transmission rate between sexual partners is low compared with other sexually transmitted diseases and was found to be not more than 50%. The incidence of GI is also relatively low among both prostitutes and their conjugal partners. Nevertheless, this disease predominantly affects sexually active individuals.3 Moreover, donovanosis, being an ulcerative disease, increases the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission.4–6 Transvaginal transmission of donovanosis during delivery has been reported, with an apparent predilection to ear structures of the newborn.7,8 Patients tend to belong to the low socioeconomic classes. No racial predilection has been proved,9–11 and both male and female predominance have been reported.5,6,11 Afflicted people are likely to delay seeking medical attention due to the painless nature of the ulcers and the possible embarrassment or fear from medical or surgical intervention. Late cases can be very debilitating and are much more difficult to manage.12

GI is endemic in warm, moderately humid areas like South Africa, India, Southern China, and Brazil.5,13 There are new endemic areas of donovanosis, mainly South and Central America, India, and Papua New Guinea,12 but the overall incidence of GI seems to be decreasing, especially in Papua New Guinea.1 The disease has nearly been eradicated from Australia, with only five cases reported in 2004,14 and is rare in North America and Europe.15–17

Etiology

Donovanosis is caused by the organism Klebsiella granulomatis, previously called Calymmatobacterium granulomatis. The name has been changed after sequencing the phoE and 16S ribosomal RNA genes and demonstrating close homology with Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis.5,12

K. granulomatis is a Gram-negative, nonmotile, pleomorphic bacterium that stains well with Giemsa, Wright’s, or silver stains but is periodic acid-Schiff-negative. The mature form is encapsulated, while the immature form is not. The immature nonencapsulated form may assume a closed-safety-pin appearance due to bipolar chromatin densities.

It is difficult to culture and store this organism; however, it may be cultured using embryonic chick heart or chick embryo amniotic fluid. It has also been cultured in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells after decontaminating the specimen with amikacin, vancomycin, and metronidazole,12 and in HEp-2 cells after adding gentamicin and cycloheximide.5

K. granulomatis is a facultative organism that resides in the cytoplasm of large mononuclear cells. It is pathogenic only to humans and the developing chick embryo. It was isolated from the feces of two out of four patients with donovanosis, although it has not been successfully cultured from feces. It is still unknown if this organism has a natural habitat.18

The incubation period extends from 3 days to 3 months but is usually 2–3 weeks. Single or multiple papules or nodules later develop and grow into a painless ulcer that may extend to the adjacent tissues and moist folds, forming “kissing lesions.” The penis, scrotum, and glans are the most commonly affected sites in males; and the labia and perineum are most commonly affected in females.11 Vaginal and cervical involvement has also been reported and sometimes mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma.5 In one case report, GI has mimicked ovarian cancer presenting as a pelvic mass.19 The anus and colon may be infected, especially in homosexual males.5,20

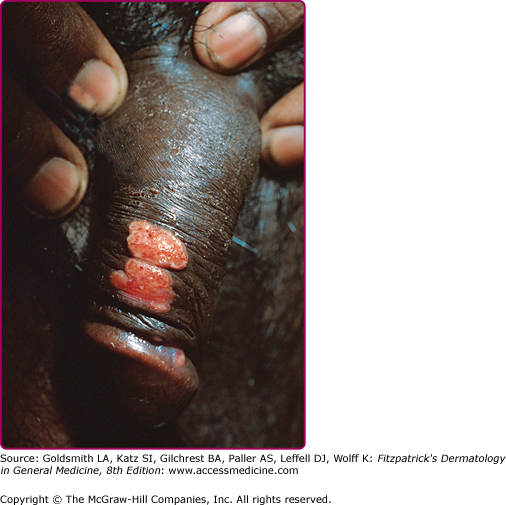

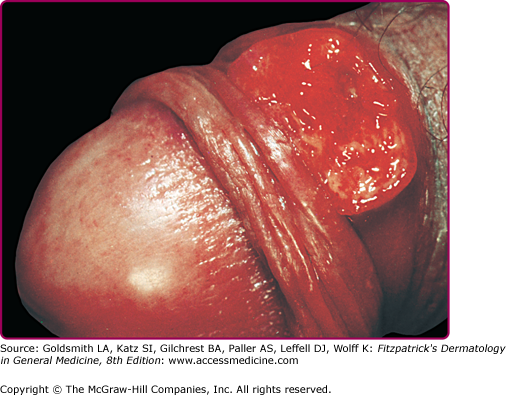

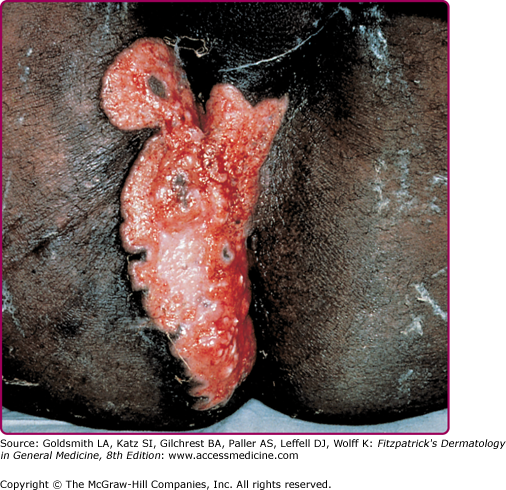

GI most commonly presents as beefy red, easily bleeding, foul-smelling ulcers with granulation tissue5 (Fig. 204-1). The ulcers may have hypertrophic or verrucous borders resembling condylomata acuminata.16 It may also present as soft, red nodules that eventually ulcerate (Fig. 204-2). In long-standing donovanosis, the lesions may be necrotic, quite destructive of tissue, and have a copious gray, foul-smelling exudate (Fig. 204-3).5,16 The tissue overlying the regional lymph nodes may evolve into an abscess or pseudobubo that later ulcerates.5 The lymph nodes per se are rarely involved unless there is a bacterial superinfection.16 In the rare dry cicatricial form, the nonbleeding ulcers form band-like scars and lead to digital lymphedema due to constriction.16

HIV coinfection may alter the clinical presentation of GI. The natural history is usually more rapid, and ulcers may persist for longer periods, lead to more tissue destruction, and need more prolonged antibiotic treatment. In addition, HIV patients with GI may have concomitant infection with other organisms such as those causing malacoplakia (most commonly Escherichia coli), which has been reported in GI of the cervix in two AIDS patients.21 Furthermore, extragenital dissemination of GI has been reported in HIV-positive patients.15

Demonstrating the Donovan bodies on smear or biopsy specimen makes the diagnosis of GI, although they are more easily visualized with properly done smears rather than biopsy (Fig. 204-4).16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree