Granuloma Annulare: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Granuloma annulare is a relatively common disorder.3 It occurs in all age groups, but is rare in infancy.3–5 The localized annular and subcutaneous forms occur more frequently in children and young adults. The generalized variant is more common in adults. Many studies report a female preponderance,3 but some have found a higher frequency in males.6 Granuloma annulare does not favor a particular race or geographic area, with the possible exception of the perforating type, which may be more common in Hawaii.7

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology of granuloma annulare is unknown, and the pathogenesis is poorly understood. Most cases occur in otherwise healthy children. A variety of predisposing events and associated systemic diseases is reported, but their significance is unclear. It is possible that granuloma annulare represents a phenotypic reaction pattern with many different initiating factors.12

Nonspecific mild trauma is considered a possible triggering factor because of the frequent location of lesions on the distal extremities of children. An early study of subcutaneous granuloma annulare found a history of trauma in 25% of children,3 but this observation has not been replicated. Trauma is also a suspected factor in auricular lesions.13 Granuloma annulare has occurred after a bee sting,14 a cat bite,15 and an octopus bite,16 and insect bite reactions have also been implicated.3 There is a report of perforating granuloma annulare in long-standing tattoos.17 Widespread lesions have developed after waxing-induced pseudofolliculitis18 and erythema multiforme minor,19 and in association with systemic sarcoidosis.3,20 Severe uveitis without other evidence of sarcoidosis has occurred in a few patients with granuloma annulare.21,22,23

There are several reports of the development of granuloma annulare within herpes zoster scars, sometimes many years after the active infection.24 It is also described after chickenpox.25 Generalized, localized, and perforating forms of granuloma annulare may occur in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (see eFig. 44-0.1).26–31 Adenovirus was isolated from a lesion in one HIV-positive patient.32 Epstein–Barr virus was excluded as a causative agent in these cases.26,27 However, in other instances generalized granuloma annulare has been linked to viral infections, including Epstein–Barr virus infection,33 chronic hepatitis B,34 and hepatitis C.35 Vaccinations for tetanus,36 diphtheria toxoid,37 and hepatitis B vaccination38 have been implicated as triggering factors, although vaccination sites were spared in one case of generalized granuloma annulare.39

Lesions compatible with granuloma annulare may occur in patients with active tuberculosis.12 There are also reports of granuloma annulare after tuberculin skin tests3 and Bacille Calmette-Guérin immunization.40 Evidence of Borrelia burgdorferi infection was detected in two reports,41,42 but this association was not confirmed in a serologic study.43 A case in which chronic relapsing granuloma annulare flared during scabies infestation was attributed to the Koebner phenomenon.44

Granuloma annulare with a predilection for sun-exposed areas45–48 and seasonal recurrence45 has been described. Photosensitive granuloma annulare has been observed in patients with HIV infection.49 One patient developed generalized disease after psoralen plus ultraviolet A (UVA) light therapy,50 but it is of note that phototherapy and psoralen/UVA phototherapy have also been used to treat generalized granuloma annulare.51–54

Actinic granuloma, also known as annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, develops on photodamaged skin and is believed to represent a granulomatous reaction to actinic elastosis.55 Its relationship to granuloma annulare is debated.

Granuloma annulare-like drug reactions are reported for gold therapy and treatment with allopurinol, diclofenac, quinidine, intranasal calcitonin, and amlodipine.56

An interstitial granulomatous drug reaction linked to the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and other medications is considered a distinct entity but may mimic granuloma annulare.57–59

Development of granuloma annulare in patients with diabetes mellitus is extensively documented. Whether this is a true relationship has long been debated. The link is primarily with type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes,60 but cases are also reported with type 2 noninsulin-dependent disease.61–63 Localized60 and generalized46,63,64 as well as subcutaneous nodular61,65,66 and perforating5,7 forms of granuloma annulare have been observed. Granuloma annulare rarely predates the onset of diabetes.60,66 The histopathologic similarity between granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum and the coexistence of both conditions in occasional diabetic patients62 suggest a true association. However, most patients with granuloma annulare do not have diabetes mellitus. Studies attempting to establish a causal correlation have yielded conflicting results.60,67,68

Granuloma annulare has also occurred in a number of patients with thyroiditis, hypothyroidism, and thyroid adenoma.64,69–72

An association between granuloma annulare and malignancy in adult patients is reported primarily with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including mycosis fungoides, Lennert lymphoma, B-cell disease,73–76 T-cell leukemia/lymphoma,77,78 and angioblastic T-cell lymphoma.79 It is reported less commonly with myeloid leukemias80 and with solid tumors, particularly of the breast.46,73 The skin lesions of cutaneous lymphoma and other hematologic malignancies can mimic granuloma annulare both clinically and histopathologically.81,82 It may be difficult to distinguish whether they represent true granuloma annulare with atypical lymphocytes, or cutaneous lymphoma obscured by a granulomatous infiltrate.75,76

The pathogenetic mechanisms that result in foci of altered connective tissue surrounded by a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate are not understood. Proposed mechanisms include (1) a primary degenerative process of connective tissue initiating granulomatous inflammation,83 (2) a lymphocyte-mediated immune reaction resulting in macrophage activation and cytokine-mediated degradation of connective tissue,30,84–88 and (3) a subtle vasculitis or other microangiopathy leading to tissue injury.84

Clinical Findings

The typical history is of one or more papules with centrifugal enlargement and central clearing. These annular lesions are often misdiagnosed as tinea corporis and treated unsuccessfully with topical antifungal agents. Subcutaneous nodules may raise suspicion about malignancy or rheumatoid disease.89

Granuloma annulare is usually asymptomatic. Mild pruritus may be present, but painful lesions are rare.90,91 Nodular lesions on the feet may cause discomfort from footwear.92 Cosmesis is often a concern for adolescent and adult patients, particularly with generalized disease.

Clinical variants of granuloma annulare include the localized, generalized, subcutaneous, perforating, and patch types. Linear granuloma annulare,93,94 a follicular pustular form,95 and papular umbilicated lesions in children96 have also been described. There is overlap between the different variants, and more than one morphologic type may coexist in the same patient.

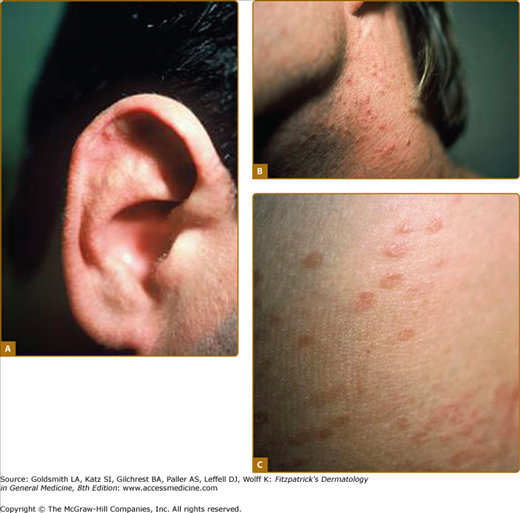

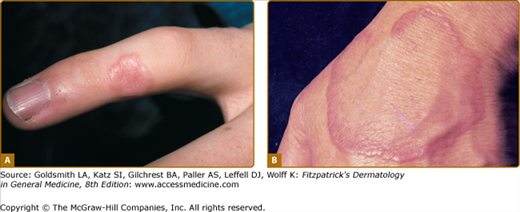

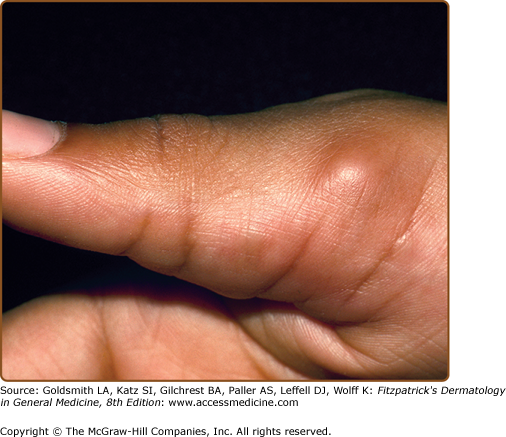

The most common form of granuloma annulare is an annular or arcuate lesion. It may be skin colored, erythematous, or violaceous. It usually measures 1–5 cm in diameter.3 The annular margin is firm to palpation and may be continuous or consist of discrete or coalescent papules in a complete or partial circle (Fig. 44-1). The epidermis is usually normal, but surface markings may be attenuated over individual papules. Within the annular ring, the skin may have a violaceous or pigmented appearance. Solitary firm papules or nodules may also be present. Papular lesions on the fingers may appear umbilicated.

The dorsal hands and feet, ankles, lower limbs, and wrists are the sites of predilection (see Figs. 44-1 and 44-2). Less commonly, lesions occur at other sites, including the eyelids.97 The palms and soles are occasionally involved.90,91 Localized annular lesions may coexist with the subcutaneous or patch forms.

The generalized form of granuloma annulare is said to comprise 8%–15% of cases.3,46 The majority of patients are adults, but it may also be seen in childhood.46,98 Unlike in localized disease, the trunk is frequently involved, in addition to the neck and extremities. The face, scalp, palms, and soles may also be affected.46

Generalized granuloma annulare presents as widespread papules (Fig. 44-3A), some of which coalesce to form small annular plaques or larger discolored patches with raised arcuate and serpiginous margins (see Fig. 44-3B). Lesions may be skin colored, pink, violaceous, tan, or yellow. An annular or nonannular morphology may predominate.46 A generalized form of perforating granuloma annulare has also been described.5,7

The subcutaneous form of granuloma annulare occurs predominantly in children,89,99,100 but is also described in adult patients.101–103 It is characterized by firm to hard, usually asymptomatic nodules located in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissues. They may extend to underlying muscle, and nodules on the scalp and orbit are often adherent to the underlying periosteum.

Individual lesions measure from 6 mm to 3.5 cm in diameter.100,104 They are distributed most often on the anterior lower legs in a pretibial location.99 Other sites of predilection are the ankles, dorsal feet, buttocks, and hands.103,105 Nodules on the scalp,104,106 eyelids,107–109 and orbital rim65,110,111 may present a diagnostic challenge. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare may also be found on the penis.112–114

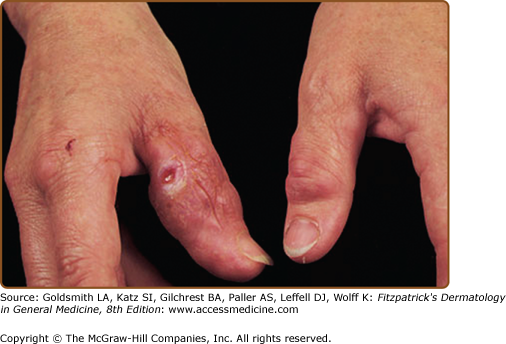

The perforating type of granuloma annulare is a rare variant characterized by transepidermal elimination of the necrobiotic collagen. It may be localized, usually to the dorsal hands and fingers (see eFig. 44-3.1), or generalized over the trunk and extremities.5,7 It has been described on the ears,115 on the scrotum,116 and within herpes zoster scars and tattoos.16 Superficial small papules develop central umbilication or crusting, and there may be discharge of a creamy fluid. Lesions heal with atrophic or hyperpigmented scars. In one series, 24% of patients complained of pruritus and 21% of pain.117 Papular umbilicated granuloma annulare on the hands of children96 and a generalized follicular pustular type of granuloma annulare95 may be clinical variants.

Macular lesions that present as erythematous, red–brown, or violaceous patches without an annular rim are reported in adult women.88,118 An arcuate dermal erythema is also observed. Generalized confluent erythema has been described in an HIV-positive patient.30

Most patients with granuloma annulare are healthy and have no other abnormal physical findings. Arthralgia is reported in association with painful lesions on the hands.91 Granuloma annulare-like skin lesions and joint disease characterize a multisystem disorder described as interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with arthritis.119

Oral involvement was observed in one patient with HIV-associated disease.27

Laboratory Tests

A diagnosis of localized granuloma annulare is made on clinical examination, and further evaluation is rarely indicated. Biopsy to obtain a specimen for histopathologic examination is necessary when the presentation is atypical, when lesions are symptomatic, and when the diagnosis is otherwise in doubt. Histopathologic analysis may be required to confirm a diagnosis of generalized granuloma annulare or subcutaneous nodular disease on the head and orbital region.

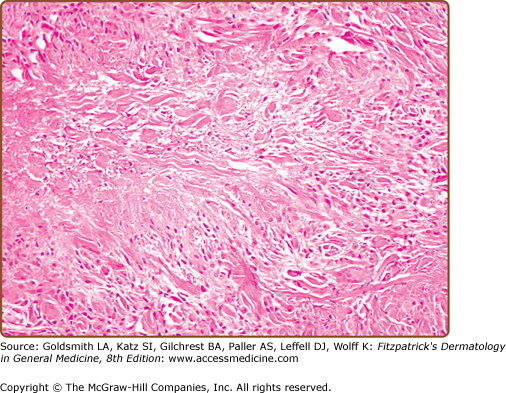

The diagnosis is best made at low magnification. Changes are usually observed in the upper and middle dermis, although any part of the dermis or subcutis can be involved. The characteristic histopathologic finding is a lymphohistiocytic granuloma associated with varying degrees of connective tissue degeneration and mucin deposition. The inflammatory infiltrate may have a palisaded or interstitial pattern, or a mixture of both patterns.120–122 Occasionally, a sarcoid-like pattern with large epithelioid histiocytes is seen.120

The typical appearance is of single or multiple foci of inflammation with a central core of altered collagen (necrobiosis) surrounded by a wall of palisaded histiocytes (Fig. 44-4). The necrobiotic centers are usually oval, slightly basophilic, devoid of nuclei, and marked by a loss of definition of the collagen bundles and diminished or absent elastic tissue fibers. Stains for mucin and lipid often give positive results.

An interstitial, nonpalisaded pattern of inflammation with histiocytes infiltrating among fragmented collagen bundles may be predominant, particularly in the generalized form. This interstitial pattern is also observed in the absence of apparent connective tissue change. Stains for mucin may be helpful in detecting connective tissue alteration within the infiltrate.

Lymphocytes are admixed with histiocytes in the granuloma and in a perivascular distribution. Multinucleated giant cells may be present but are not as numerous as in actinic granuloma.123 Neutrophils and eosinophils are occasionally seen, but plasma cells are rare. Evidence of vascular reactivity includes variable endothelial cell swelling, red cell extravasation, fibrin, leukocytoclasis, and neutrophilic infiltration in blood vessel walls.124 When leukocytoclastic vasculitis or nuclear debris is a prominent finding, a diagnosis of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis of immune complex disease should be considered.124

In subcutaneous granuloma annulare the foci of necrobiosis are larger and lie within the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat. They may be distinguished from rheumatoid nodules by the presence of mucin in the necrobiotic zone.107 Central ulceration and communication between the area of necrobiosis and the surface are characteristic of perforating granuloma annulare. Examination of serial sections may be necessary to demonstrate the necrobiotic plug. An interstitial pattern of inflammation with diffuse necrobiosis is reported in the patch type of granuloma annulare.119 Palisaded granulomas have also been observed in macular lesions.88

Immunofluorescence testing may show deposition of fibrin, immunoglobulin (Ig) M, and C3 as a variable finding around vessel walls or at the basement membrane zone; IgM cytoid bodies are also reported.119 Immunohistochemistry may be useful to confirm the histiocytic nature of equivocal disease.125 Ultrastructural changes in the connective tissue and capillaries have been described.83

A diagnosis of granuloma annulare is made clinically or by skin biopsy. Special investigations are usually not necessary. Further evaluation to rule out systemic disease such as infection, sarcoidosis, or malignancy may be required in atypical cases of granuloma annulare.12,77,81,82,118 Investigation for endocrine disease is indicated if the patient has signs or symptoms of diabetes or thyroid dysfunction.

Imaging studies may be performed in subcutaneous granuloma annulare when the clinical features are not recognized or when the presentation is atypical with rapid enlargement or pain.126 Radiographs show a nonspecific soft tissue mass without calcification or bone involvement. Ultrasonographic examination reveals a hypoechoic area in the subcutaneous tissues.126,127 Magnetic resonance imaging shows a mass with indistinct margins, isointense or slightly hyperintense to muscle with T1-weighted images and with a heterogeneous but predominantly high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.126

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree