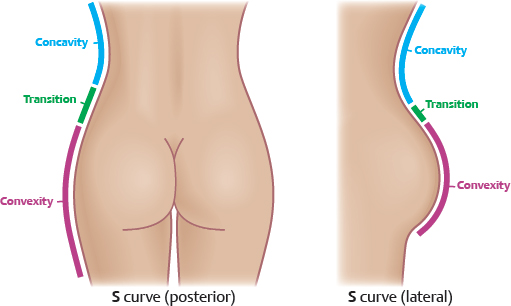

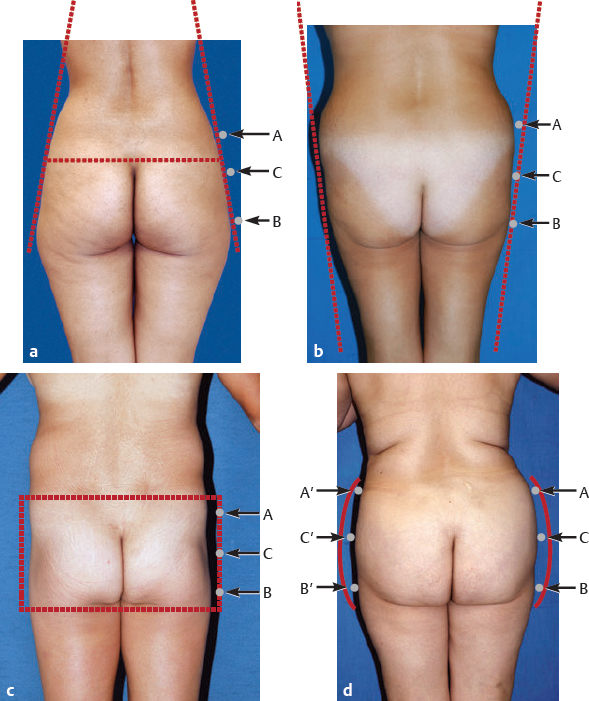

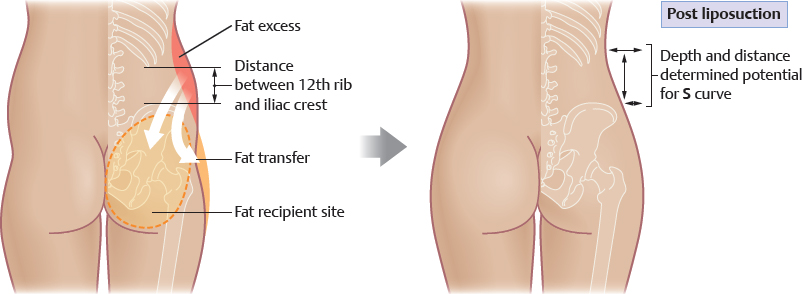

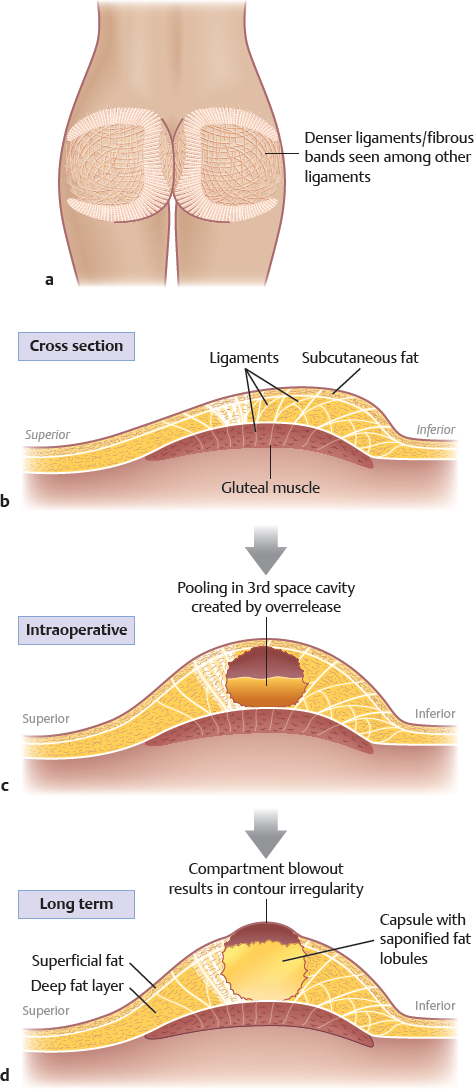

CHAPTER Gluteal augmentation has been performed with increasing frequency for nearly 5 decades. The first reported case, described by Bartels in 1969, used a breast implant to treat gluteal idiopathic atrophy.1 Over the ensuing years, augmentation of the gluteal region has been performed using implants designed specifically for the purpose, autoaugmentation with local flaps, and, increasingly, with autologous fat transfer.1–7 All modalities of gluteal augmentation have undergone an evolution of technique resulting in greater predictability with an improved complication profile. This refinement is perhaps most notable in gluteal augmentation with fat transfer. This is by far the most commonly performed method for gluteal contouring and augmentation today. We have seen an explosion in buttock-enhancing procedures since 2010. Popular media, social media, and Internet popularity of certain female icons of modern beauty have placed a large focus on buttock shape and curvier body silhouettes. There are several advantages of gluteal augmentation with fat transfer compared with other methods.2,3,6 The procedure uses entirely autologous tissue, avoiding the compli cations associated with an implant (capsular contracture, implant migration or rotation, wound-healing complications, thinning of native tissues, and implant-associated infectious complications). It allows for detailed contouring of the entire gluteal area, allowing focused augmentation of specific areas of the region as dictated by anatomic need and patient preference (unlike implant-based augmentation or autoaugmentation using flaps, which have a more limited region of augmentation). The harvesting of fat by liposuction allows for comprehensive or focused torso contouring with a more profound global result. The reduction of fat in the lower back, flanks, thighs, and even more distant sites provide a powerful global body contouring effect combined with augmentation of the gluteal region. The subtraction of fat from the lower back and adjacent torso, with simultaneous addition of fat graft to the buttocks superiorly and medially, provides the 360– degree “curve” visual enhancement that is desirable. The result is an overall body silhouette in which concavities flow to adjacent convexities creating a pleasing and sensual S curvilinear body reshaping (Fig. 32.1). Despite its advantages, gluteal augmentation using fat transfer has its limitations. Without sufficient fat for augmentation, the procedure may provide less than desired augmentation.6 In addition, fat grafting may be unpredictable or subside to less than desirable volume over time. Other complications noted with gluteal fat transfer include fat necrosis, infection, erythema, abscess, hematoma, seroma, contour irregularities, asymmetry, sciatic nerve injury, fat embolism, thromboembolism, and death.8–10 Over the past decade, refinements in patient selection, surgical technique, and postoperative management have dramatically improved the short- and long-term results associated with gluteal fat augmentation. The procedure has evolved to one with a more consistent and predictable result and a dramatically reduced complication profile that is arguably superior to other modalities of gluteal augmentation. This chapter provides an overview of our approach to patient selection, surgical technique, and postoperative care, with special attention to details that optimize results and help avoid complications. It also discusses the management of complications that may arise from gluteal augmentation with fat grafting. Box 32.1 reviews the overall pitfalls that can lead to undesirable aesthetic results, poor patient satisfaction, or true surgical complications. Preoperative • Poor patient analysis • Inadequate patient consultation • Unrealistic expectations • Poor understanding of fat graft outcomes and limitations • Patient factors Intraoperative • Poor liposuction technique • Improper handling of fat grafts • Excess compression • Fat compartment blowout • Pooling of large fat aliquots • Neurovascular trauma Postoperative • Compression or pressure of fat graft recipient sites • Thromboembolic complications Summary Box Complications Associated with Gluteal Augmentation • Capsular contracture • Implant migration • Implant rotation • Improper wound healing • Thinning of native tissues • Implant-associated infection • Fat necrosis • Erythema • Abscess • Hematoma • Seroma • Contour irregularities • Asymmetry • Sciatic nerve injury • Fat embolism • Thromboembolism • Death Appropriate patient selection and education is critical to the success of any cosmetic operation. The ideal patient for gluteal fat augmentation should have sufficient donor fat to allow for an appreciable gluteal augmentation. Very thin patients are generally considered poor candidates for the procedure; however, in some cases, thinner patients can have a dramatic global torso transformation simply as the result of a modest liposuction and fat augmentation to very select zones of the gluteal region. In some cases, when patients have marginal or insufficient quantities of fat for gluteal augmentation, they can be instructed to gain weight with a diet focused on gaining and increasing fat lobule size to improve lipoaspirate yield. It is critical to have a thorough discussion with the patient and explain what the procedure can and cannot accomplish for that individual. As in any plastic surgical procedure, expectation management is of paramount importance. Reviewing preoperative and postoperative photos of other patients, particularly with similar body frame and tissue characteristics, helps demonstrate achievable results and elucidates limitations of the procedure. The magnitude of gluteal contour improvement achievable is rooted in the patient’s anatomic morphology and surgical precision. The consultation should include a careful discussion of the risks associated with the procedure along with the inherent unpredictability of fat graft survival and longevity of the overall “new” buttock shape. It cannot be overemphasized that in the current online and social media climate, “selfies,” and numerous applications that help people alter their photographic images, patient education is becoming more vital. Without a collective effort by board-certified plastic surgeons in cohesive dissemination of honest information on long-term “true” results and limitations and/or risks, there will exist a far greater challenge in the near and distant future. A lack of informed decision-making will directly lead to unrealistic expectations and increased complication rates. Patients will see postoperative examples taken too early (with much of the visualized gluteal volume resulting from edema and ultimately nonviable fat grafts) or edited photos on social media or, worse, on surgeons’ websites, and expect these results. An honest plastic surgeon may lose that patient to someone less experienced or less interested in technical acumen and ethical practice standards. The results in fat grafting, more than any other aesthetic procedure, require a minimum of 6 months to a year to assess. Patients with preexisting medical comorbidities or who are older than 40 years should receive appropriate medical clearance. It is very important to review all medications, supplements, herbs, and other substances that the patient is taking and instruct the patient to cease taking any that may predispose to perioperative complications (vitamin E, fish oil, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, weight loss supplements, etc.). Thromboembolic risk factors should be scrutinized and discussed with patients. Smoking and nicotine use (vaporized or directly consumed) may greatly compromise fat graft viability by limiting blood flow to the fat grafts. A lack of proper vasodilation and neovascularization can reduce the delivery of proper nutrients for fat graft survival. Patients who have unrealistic expectations or who are psychologically compromised should have repeat consultation(s), formal psychological evaluation, or refusal of the procedure (often the wisest course). A classic example is someone who desires disproportionately large buttock size. As with oversized breast implants, overexpansion of the surrounding tissue envelope and scaffold will cause severe deleterious effects. This is even less predictable than in breast augmentation, because the long-term volume effect is not fixed as it is with an implant. The surgeon should not resort to “overcorrection” for this reason. Proper technical planning and execution are directly related to preoperative evaluation and thorough discussion with the patient regarding aesthetic goals. As mentioned previously, successful outcomes should rely less on volume of augmentation than on optimal gluteal shape and how this shape relates to overall body contour. The goal of this chapter is to discuss possible complications and how to prevent them; therefore details on aesthetic planning and classifications of buttock shape are outside the chapter’s scope and intent. However, it is important to review general aesthetic guidelines. There are four general types of trunk/buttock shapes6 (Fig. 32.2): 1. A-frame 2. V-frame 3. Square 4. Round Understanding the limitations on how V– and H-frames can be altered to the more desirable A-frame (or upsidedown heart) shape is paramount to avoiding overzealous injection, particularly in zones that notoriously have less fat graft survivability (midlateral and inferolateral areas). For example, to change a V-frame to a more optimal waist–hip ratio optimally requires a certain distance between the 12th rib and iliac crest (Fig. 32.3). The deeper the muscular attachments and the longer the distance, the more liposuction in this area can excavate the flank and create depth. In addition, lateral buttock augmentation and expansion of width is often hardest to achieve in the anatomic region that may need it most. The lack of neighbor fat cells here, along with essentially skin, thin subcutaneous fatty depth, and tensor fascia lata, makes it a challenge to alter the scaffold and establish a favorable environment for fat graft survival (Fig. 32.4). Excessive fat transfer here often leads to less graft survival and can lead to cyst and third-space cavities or frank seromas. However, selective release, grafting, and precise and limited re-release allows for appropriate expansion and fat take. The patient should be marked in the standing position. Planned areas of liposuction should be marked in a standard fashion, with emphasis on the zones adjacent to the buttock. There are many different surgeon preferences in marking the buttock for gluteal augmentation. Although knowledge of certain classifications or gluteal zones is helpful, clinical markings do not need to adhere to these. More simply, areas requiring both release and different capacity for accepting fat grafts are marked. Markings are based on several factors including skin laxity, fat and muscle fullness, and bony structure. It is important to assess the lateral–trochanteric region for enhancement, because it can significantly contribute to the lateral contour of the gluteal profile. The iliac crest should be noted and serves as the lowest point of liposuction and the upper edge of the gluteal region. The patient should be assessed to determine whether elevation of the gluteal contour or additional fullness in the iliac crest are needed. There are often areas of dimpling throughout the gluteal region or an oblique fascial band at the inferomedial border of the buttock; these should be noted and marked, because they require “selective” release intraoperatively. Fig. 32.2 Mendieta’s frame shapes to evaluate overall bony frame and the consequent buttock–body relationship. (a) A-frame. (b) V-frame. (c) Square. (d) Round. A, Upper lateral hip; B, midbuttock; C, lateral leg. (Reproduced from Mendieta CG. The Art of Gluteal Sculpting. New York: Thieme; 2011:11.) Fig. 32.3 Flank shape potential. The distance between the caudal ribs and iliac crest along with iliac crest height and shape influence the potential depth of the flank and waist excavation and degree of waist–hip ratio possible. Fig. 32.4 In the midlateral and inferolateral gluteal region it is usually more challenging to ensure great fat graft survival secondary to a poor native scaffold and inadequate “neighbor” fat cells. The skin and subcutaneous layer are typically adherent to tensor fascia lata with less room for expansion. This patient has a lack of native scaffold, poor capacitance, and poor osseous morphology. The preoperative marking session is the last, and arguably best, time to clearly delineate to the patient what areas are planned for reduction and augmentation. It is helpful to discuss with the patient which areas they feel strongest about augmenting, particularly in cases where there may not be enough fat to augment all areas of the buttock. The patient should be offered the opportunity to prioritize several zones, such as upper buttock fullness, posterior projection, posterolateral buttock fullness, or lateral hip–trochanteric fullness. The patient may be prepped for surgery with a standing prep or in multiple steps throughout the operation. Sequential compression devices must be used, and the patient should be given a dose of preoperative or perioperative antibiotics within an hour of incision (and should be redosed after 4 hours if the surgical duration allows for that). Performing the procedure with general anesthesia allows for greater flexibility in the operation. There are many approaches to patient positioning during surgery. We prefer to begin the operation with the patient in the supine position and turn the patient prone to complete the procedure. The procedure may also be performed with an alternating lateral decubitus position, but we do not believe this allows for good visualization of gluteal symmetry and creates abnormal buttock contour and tissue splaying. It is critical that all pressure points are protected, particularly with the patient in the prone position (axillary rolls, facial padding, elbow padding, and a horizontal cushioning of the iliac crests, etc.). Liposuction is performed in the standard fashion using the surgeon’s preference for tumescence and cannulae. We prefer high-oscillation cannula-tip aspiration (power-assisted) lipoaspiration. The main layer targeted is the subscarpal layer, with large (4 and 5 mm) cannulas that allow for adequate fat removal and comprehensive redraping of the tissues postoperatively. A 4- to 5-mm cannula diameter allows the fat lobules in this large volume grafting to be minimally traumatized and more viable. Smaller cannulas are used to target superficial cellulitic areas and for more superficial lipodystrophy. Sometimes vibration is used without suction to release superficial and deeper bands before performing liposuction. Pretunneling and posttunneling are a highly effective way to mobilize the fat layer to be aspirated, and helps even out the remaining tissue layers during postoperative healing.11,12 As with all liposuction, it is critical to use multiple access incisions with crisscrossing passes at multiple depths to avoid contour irregularities. We believe special attention should be paid to aggressive liposuction of the lower back, central fat pad (sacral area), and flanks. It is the area just above the central gluteal border that can often blunt the degree of upper pole gluteal projection. With removal of this area of lipodystrophy, there is an apparent greater lower back lordosis with an appearance of greater superior gluteal projection. This is what is colloquially called a “shelf.” Excessive liposuction in the sacral area can destroy the lymphatics similar to the mons pubis area, leading to an increased prevalence of seromas in this region. Seromas are more common in these two locations and typically resolve with simple one-time or serial aspirations in the office. Not adhering to the basic liposuction techniques listed previously may result in donor site irregularities or inadequate fat graft acquisition, both of which are undesirable. Fat preparation is a critical step; the surgeon must not deviate from protocol and must be meticulous in every stage. There are many approaches to processing of the lipoaspirate, with an increasing number of devices (often expensive) used for it.13,14 Although the details may differ, the principles remain the same: the goal is to separate the viable fat in a sterile fashion from the aqueous component and prepare it for transfer to the buttock. Our approach to fat preparation is to drain or aspirate out the aqueous component of the lipoaspirate once the fat has decanted in the liposuction canister (Fig. 32.5). The fat is then strained through a commercial strainer, without touching the fat, removing further aqueous components and obtaining a greater content of more purified fat lobules. The fat is mixed with a total of 300 mg clindamycin solution for each strained batch. The fat is then transferred into 60-mL Toomey syringes and prepared for injection to the gluteal region (Fig. 32.6). The strainers are covered with towels or paper to avoid theoretical contamination in this open, exposed part of processing. Although proponents of closed systems claim contamination is an issue, there has been no evidence to suggest that infection rates are increased or viability rates are reduced with this processing technique. In more than 1,000 buttock fat transfers using the simple technique described here, I (A.G.) have seen only three infections, and all resolved with simple incision and drainage, with no need for further revision or regrafting. Fat transfer is the most technically unforgiving component of the procedure. The fat is susceptible to injury or death from shearing, nutritional depletion, excessive pressure, and other factors.13 Great care must be taken to place the fat properly into the appropriate anatomical regions and to avoid neurovascular complications to the patient and cytotoxic complications to the transplanted fat. The single most important component to ensure success of fat transfer is to lay multiple small aliquots of fat so that the injected fat is surrounded by healthy, well-vascularized tissue and surrounding native fat cells. It is important to avoid pooling of fat into large aliquots, because they may progress to areas of fat necrosis or liquefaction. We use 3.7-mm cannulae to inject the fat and do so during advancement and retraction of the syringe (Video 32.1). Strokes should be rapid, in a fanning motion, not staying in one location for long. Typically no more than 5 to 10 cc of fat per pass is injected. As with liposuction, it is critical to perform multiple passes in multiple directions to ensure an even and homogenous distribution of fat. We inject fat into the subcutaneous and superficial muscular layers only, beginning deep and moving more superficial. Avoidance of the deeper muscular layers is critical to avoid intravascular injection and injury to the sciatic nerve (Video 32.2).10 Fat lobules placed in syringes should not be excessively aqueous nor contain ligamentous and fibrous tissue. Revision and secondary liposuctioned zones will contain scar and fibrous tissue, which will be aspirated and require removal from injected aliquots. These both complicate the necessary tension feedback required to optimally judge injection volume required or possible per area. Some tissue resistance should be felt with every pass to avoid inadvertent pooling of fat lobules. This third spacing can cause future cyst formation and potential saponification of sterile fat (Fig. 32.7). Overcorrection is not recommended, because excessive injection may result in greater pressure placed on the transplanted fat—a potentially cytotoxic event.13 Excessively aqueous fat grafts will overestimate actual volume of viable fat cells injected. This may make the patient feel good, because many want a certain amount of volume and determine success on this number. However, this will lead to unrealistic expectations. A viable fat ratio is approximately 30 to 50% of aspirate volume. For example, if 3 L are aspirated, up to 1,500 mL may be usable fat grafts. The factor that determines this is the density of fat cells per area. Volumes may be less in secondary cases or weight loss patients. Areas of gluteal dimpling may be released with percutaneous aponeurotomy using an 18-gauge needle. We often use a small pickle-fork cannula to release a lower central fascial band of the buttock. Access incisions are closed using a layered technique. The nature of sterility and viability of fat grafted sites requires watertight closure of incisions, particularly those of the buttock and lumbar area. Open drainage should not be used. Compression of the areas of liposuction is important to prevent seromas and ensure good adherence of the skin and superficial fat layers to the musculoskeletal framework. We place one or two layered Topifoam adhesive pads (Mentor Aesthetics) over the area of the lower back central (sacral/suprasacral) fat pad to help enhance the desired lower back lordosis. We then place Topifoam foam over the areas that have undergone liposuction and place the patient into a compression garment. Fig. 32.7 Overrelease of deep ligaments and fat compartment borders. Third spacing can result in fat “pooling” and subsequently alter fat take. (a) Ligament distribution varies in each buttock but is similar to Cooper’s ligaments in the breasts. (b) Cross-sectional relationship of ligaments from the muscle to the superficial subcutaneous fat layer. (c) Overrelease of ligaments and/or overexpansion with excess volume can create a pooling of fat cells in the third spacing that is created. (d) Over the long term, “fat compartment blowout” can create a non-contractile soft tissue envelope and an encapsulated cystic cavity containing saponified fat cells and liquid (usually sterile). Patients are given antibiotics for 5 days postoperatively. The Topifoam pads are removed 7 to 10 days after the operation and are replaced as needed. The patient is instructed to use the surgical garment for up to 2 months after the operation, changing from first stage (two zippers) to second stage (one zipper). Pads are usually not needed when the second stage compression is used. Because compression on augmented buttocks can result in fat graft death, the patient is instructed to avoid sitting or lying on the buttocks for the first 2 weeks and up to 8 weeks as much as feasible. This includes prone positioning when sleeping and sitting with pillows underneath the thighs, keeping the gluteal region off the chair. There are now many commercially available pillows designed specifically for this purpose. Another approach some patients take is to sit on an inflatable exercise ball or sit on the thighs with the buttocks off the edge of a sitting stool or chair with no back. A very important caveat to that rule is to have a very low threshold to see patients if they have any concerns or questions. The final surgical result is not noted for 3 to 6 months after surgery. After the 6-month mark, contour and volume retention does not change much further if all conditions remain the same. Patients should be educated on meticulous hygiene. Patients are instructed to ambulate immediately after surgery. Postoperatively, patients are instructed to “feed their fat.” We recommend a relatively high caloric intake for the first 1 to 3 months after surgery to ensure better fat nutrition and retention. Patients are allowed to engage in light exercise 4 weeks after the operation. We recommend that patients focus on exercises that will build and tone muscle (yoga, Pilates, weight training, etc.) rather than strenuous fat-burning exercises. Poor fat survival is perhaps the most common complaint associated with gluteal fat transfer. Reasons associated with all aspects of the operation as well as patient idiosyncrasies are responsible for why fat take may be less than desired. Perioperative factors that affect fat survival can be categorized into those associated with fat preparation, fat injection, or postoperative care (see Box 32.1).6,13,14 Fig. 32.9, later in the chapter, addresses poor fat graft survival in areas of overrelease and overexpansion. We believe that it is normal to lose anywhere from 30 to 40% of transplanted fat over 3 to 12 months. Surgical factors are reduced as much as possible to minimize this loss. From the first steps of the operation, great consideration is paid to maintaining and optimizing fat viability. The operation is performed with a sense of urgency, with care taken to minimize any wasted time. Particular at tention is paid to minimizing the amount of time between the moment fat is removed from the body and the time it is injected into the buttock. Minimizing this extracorporeal time reduces potential oxidative and ischemic injury to the adipocytes. While the fat is out of the liposuction canister, it is kept covered by a towel as a barrier to contamination and air exposure. A common topic of discussion at conferences relates to this critical step. Critics of the “open” technique of transfer from donor to recipient note a “nonsterile” nature to strainers. However, the argument is null based on vast experience and lack of literature. The simplest way to think of this is that surgeons leave many instruments and materials (meshes, sutures, and tissue matrixes) exposed throughout surgical cases and resultant infectious issues do not occur. There are many details associated with fat injection that can optimize graft take. It is critical that the fat be distributed in small aliquots (5 to 10 cc) in multiple passes to ensure that any implanted fat is completely surrounded by well-vascularized host tissue. Large aliquots of fat will result in “lakes” of fat within the buttock tissue, cyst formation, and fat loss. The central core of these large aliquots will be too far away from host tissue to receive any nutrients or oxygen by diffusion, before the graft is vascularized. This central tissue will be significantly more susceptible to loss. Another important consideration to optimize fat take during the injection process is to pay careful consideration to the total volume injected with attention to the pressure within the buttock. There is an upper limit of fat volume that can be injected to the buttock.13 This capacitance should be judged preoperatively by tissue palpation and intraoperatively based on continual and subtle changes in tissue resistance with cannula passes. Beyond a certain point, the pressure built up within the gluteal tissues from excessive fat injection can build to a point that has a deleterious effect on the transplanted fat. The graft capacity should therefore be evaluated and reevaluated throughout injection. Increased experience in large volume fat grafting will help immensely in this and all steps. Postoperatively, care is taken to nurture the transplanted fat as it transitions from a diffusion-dependent graft to vascularized tissue that has taken hold in the host environment. The most important concept in the perioperative period is to avoid pressure on the newly transplanted fat. Patients are instructed not to sit or lay on their buttocks for 2 weeks after the operation except for 20 to 30 minutes at a time on pillows for eating, toilet use, and other necessary tasks. We also believe in optimizing the nutritional support to the recently transplanted fat. We encourage patients to enjoy healthy, complex carbohydrates and protein shakes between meals. We also encourage our patients to stay well hydrated but consume a low-sodium diet to minimize postoperative edema. Finally, as previously mentioned we try to maximize fat retention by allowing exercise 4 to 6 weeks after the operation but initially discouraging strenuous “fat-burning” exercises (such as aggressive cardiopulmonary workouts) in favor of more anabolic, muscle-building or muscle-maintaining exercises such as yoga, Pilates, or weight training. The understanding of factors related to fat retention after grafting have made significant headway over the past 5 years. In general, this understanding is primarily related to operative maneuvers and techniques that improve outcomes. Future direction in research should be directed toward identifying the factors that result in differential fat take among patients and on how to control these factors. Asymmetry is not commonly a source of patient complaint and is often subtle. Preoperative native bony and tissue asymmetries in contour, size, shape, and tissue elasticity are most influential on long-term contour asymmetry. Asymmetries are also related to many factors, including differential fat viability and “take,” pressure differences in sitting postoperatively, and different donor site characteristics. However, the most important factor in managing postoperative asymmetry is preparing the patient for it preoperatively. It is critical to clearly explain and point out preoperative asymmetries and variations in iliac crest height and other bony differences as well as skin and soft tissue variations and native irregularities. Photographs aid in this process. Surgical goals can be to improve the asymmetry with differential fat grafting, but it will be impossible to completely correct, as with all bilateral plastic surgery. As has been abundantly documented in the breast augmentation literature, patients who have appropriate preoperative expectations and informed consent are substantially happier postoperatively.15 Preoperative expectations aside, striving to achieve excellent postoperative symmetry is certainly an important goal but a secondary one of this procedure. Preexisting asymmetry must be appreciated before the operation. Different quantities of fat may be injected on either side and in different subunits of the buttock as needed. As a component of the preexisting gluteal asymmetry, structural differences between the buttocks must be recognized; this includes dimpling, fascial bands, indentations, scar tissue, and skin laxity. Fascial bands, inter–fat compartment ligamentous borders, and indentations may be released using a pickle-fork, vibrating various-tipped cannula, or 18-gauge needle (superficial) intraoperatively. Indentations and areas of scar may need more fat, scar release or revision, or reduction of contralateral gluteal augmentation to match the restriction. If a patient is noted to have substantial asymmetry postoperatively, the most important first step is to wait at least 3 to 6 months after the operation to determine the final graft take. The desire and necessity for revision fat injection to correct asymmetry as a result of differential fat take is actually very rare. If the patient continues to have asymmetry after the 3 to 6 months, the most straightforward approach is to perform another fat transfer procedure to augment the side with volume deficiency (Fig. 32.8). This can be undertaken as early as 6 months, but preferably at 12 months, if donor fat is available. In performing revision augmentation, the entire buttock need not be augmented. It is more efficient to only augment the anatomical zone(s) indicated. The alternative approach of reducing the buttock with greater volume using liposuction is not recommended, because liposuction of the buttock is fraught with complications, including significant contour abnormalities and untoward ptosis. In certain cases, liposuction may be considered if it is performed in areas that were augmented outside of the buttock tissue, such as the lateral hip or supragluteal area, to improve the asymmetrical appearance.

32

Gluteal Augmentation

Smoking (tobacco use)

Smoking (tobacco use)

Suboptimal donor fat volume

Suboptimal donor fat volume

Soft tissue and bony morphology

Soft tissue and bony morphology

Donor site irregularities

Donor site irregularities

Inadequate fat graft acquisition

Inadequate fat graft acquisition

Excess trauma to fat graft lobules

Excess trauma to fat graft lobules

During processing

During processing

During lipoinjection

During lipoinjection

Lack of sterility

Lack of sterility

Poor fat graft injection technique

Poor fat graft injection technique

Tobacco use

Tobacco use

Poor hydration and calorie intake

Poor hydration and calorie intake

Weight loss

Weight loss

Early or excessive exercise

Early or excessive exercise

Unrealistic patient expectations

Unrealistic patient expectations

Avoiding Unfavorable Results and Complications in Gluteal Augmentation

Patient Selection

Surgical Planning

Intraoperative Considerations

Liposuction

Fat Preparation

Gluteal Fat Transfer

Postoperative Care

Avoiding and Managing Specific Complications in Gluteal Augmentation

Poor Fat Survival

Asymmetry

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine