Fungal Infections

Lauren Alberta-Wszolek

Aimee M. Two

Chao Li

Kathryn Buikema

Abel D. Jarell

Jessica M. Gjede

CANDIDIASIS

I. BACKGROUND

Candida albicans, a normal inhabitant of mucous membranes, skin, and the gastrointestinal tract, can evolve from a commensal organism to a pathogen causing mucocutaneous infection. Factors that predispose to infection include (i) a local environment of moisture, warmth, and occlusion; (ii) systemic antibiotics, corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents, or birth control pills; (iii) pregnancy; (iv) diabetes; (v) Cushing disease; and (vi) debilitated states. Immune reactivity to Candida is reduced in infants up to 6 months of age and in patients with lymphoproliferative diseases or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. However, most women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis have normal cellular immunity. Recently, nonalbicans Candida strains have been recognized as an important pathogen, particularly in recurrent infections.1

The resident bacteria on skin inhibit the proliferation of C. albicans. Cellmediated immunity plays a major role in the defense against infection. In addition, C. albicans can activate complement through the alternative pathway. The innate immune system appears to respond to mannan, a C. albicans cell wall polysaccharide, through toll-like receptors 2 and 4.2

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

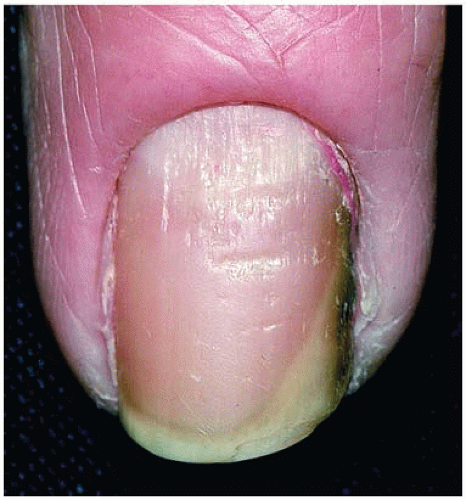

1. Paronychia (Fig. 16-1) is associated with rounding and lifting of the proximal nail fold, disruption of the cuticle, and erythema and swelling of the fingertip. The nail plate may display transverse ridging or greenish-brown discoloration. In chronic paronychia, the area surrounding the nail is tender, and there is often a history of frequent wetting of the hands.

2. Intertriginous lesions (inframammary, axillary, groin, perianal, and interdigital) (Figs. 16-2 and 16-3) are red, macerated, and sometimes fissured. The lesions are well demarcated, with peeling borders, and often surrounded by satellite erythematous papules or pustules.

3. The white plaques of thrush can be scraped from mucous membranes with a tongue blade, in contrast to the fixed lesions of oral hairy leukoplakia. The underlying mucosa is bright red. Lesions may extend into the esophagus. The discomfort of oropharyngeal candidiasis may interfere with eating.

4. Perleche or angular cheilitis (Fig. 16-4) presents with fissured erythematous moist patches at the angles of the mouth. Poorly fitting dentures or mouth breathing may be associated.

5. Candida vulvovaginitis is frequently associated with a vaginal discharge. There may be severe vulvar erythema, edema, and pruritus.

Figure 16-1. Chronic paronychia. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.) |

III. WORKUP

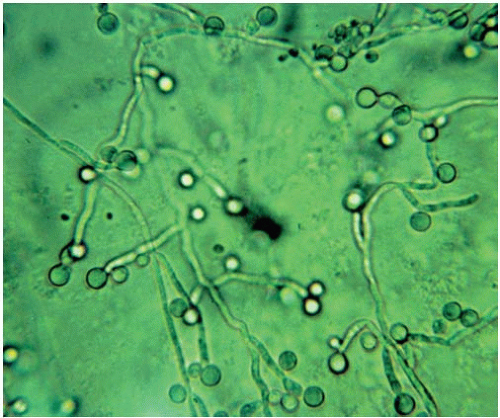

1. Direct examination of scrapings from lesions with potassium hydroxide (KOH) will reveal budding yeasts with or without hyphae or pseudohyphae (Fig. 16-5). Hyphae are almost always seen in mucous membrane infection,

but may be absent in skin infection. A rapid latex agglutination test is also available for diagnosis but offers little advantage over KOH in terms of sensitivity and specificity.3

but may be absent in skin infection. A rapid latex agglutination test is also available for diagnosis but offers little advantage over KOH in terms of sensitivity and specificity.3

2. Candida albicans grows readily within 48 to 72 hours on fungal or bacterial media. Specific identification is based on the presence of chlamydospores when the organism is subcultured on cornmeal agar.

3. Gram stain and culture of affected areas can be helpful. Gram-negative rods may play a synergistic role in infection of intertriginous areas.

IV. TREATMENT

The imidazoles (ketoconazole, miconazole, clotrimazole, and econazole) and broader-spectrum triazoles (fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole) are used most often in the treatment of candidal infections (Table 16-1). The pyridone derivative ciclopirox (Loprox) and the polyene antibiotic nystatin are also effective. The allylamines naftifine (Naftin) and terbinafine (Lamisil) and the benzylamine butenafine (Mentax) are fungistatic against Candida. Tolnaftate (Tinactin) and undecylenic acid (Cruex; Desenex) are NOT effective against Candida.

Systemic treatment of vaginal infections has become widespread. Oral imidazoles and triazoles are also useful in chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and recalcitrant candidal onychomycosis. Ketoconazole and, to a lesser degree, itraconazole have many drug-drug interactions owing to the inhibition of cytochrome P-450 3A4. Their use is contraindicated with simvastatin, lovastatin, cisapride, triazolam, midazolam, quinidine, dofetilide, and pimozide.4

A. Paronychia. Successful treatment of a chronic paronychia often requires weeks to months, and nails will grow out normally within 3 to 6 months of the paronychia healing.

1. An imidazole, such as ketoconazole (Nizoral), sertaconazole (Ertaczo), clotrimazole (Lotrimin, Mycelex), miconazole, or ciclopirox olamine (Loprox), should be applied several times a day. Other effective agents include naftifine (Naftin), haloprogin (Halotex), or nystatin.

TABLE 16-1 Top Treatment Choices for Candidal Infections | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

If there is associated pain or edema, use a combined steroid-nystatin ointment (e.g., Mycolog II) or a topical corticosteroid cream along with the antifungal agent for the first several days. Overnight application under occlusion may increase effectiveness. Oral therapy may be helpful as well. In addition, the area should be protected during wet work by wearing waterproof gloves and cotton liners.

2. Two to Four Percent Thymol in Chloroform or Absolute Alcohol is a simple and effective alternative that is applied b.i.d. to t.i.d.

3. Amphotericin B (Fungizone) Lotion or Cream or 1% Alcoholic Solution of Gentian Violet may also be used. Because amphotericin B and imidazole agents counteract one another, they should not be used simultaneously.

B. Intertriginous Lesions

1. Education about the role of moisture and maceration is important. The following techniques may be recommended: (i) drying affected areas after bathing using a handheld hair dryer on low heat, at least once a day; (ii) supportive clothing and weight reduction; (iii) air conditioning in warm environments; and (iv) regular application of a plain or medicated powder (nystatin or miconazole) to the areas.

2. For Very Inflammatory Lesions, open compresses three to four times a day with water or Burow solution (Domeboro) will expedite relief of symptoms.

3. A Topical Antifungal Cream or Nystatin or Miconazole Powder should be applied to the dried skin.

4. Gentian Violet 0.25% to 2.0% and Castellani Paint (fuchsin, phenol, and resorcinol) are older remedies, which are effective but may sting and will stain clothing, bed linen, and skin.

C. Thrush

1. Clotrimazole Buccal Troches (10 mg) five times a day for 2 weeks are usually effective for oropharyngeal candidiasis in adults and older children. The dose for infants has not been well established.

2. Alternatively, Nystatin Oral Suspension (400,000 to 600,000 units) q.i.d. is held in the mouth for several minutes before swallowing. The dosage for infants is 2 mL (200,000 units) q.i.d.

3. Oral fluconazole (50 mg daily) has been the mainstay of systemic therapy in the past.5 However, with frequent use in immunocompromised hosts, fluconazole-resistant candidiasis has been reported. In this situation, itraconazole 200 mg PO q.d. for 2 to 4 weeks may prove effective.4 Voriconazole may also be useful.6 Anidulafungin, a member of the novel class of antifungals, echinocandins, is equal in efficacy to fluconazole in the treatment of esophageal candidiasis, has few significant drug-drug interactions, and is well tolerated.7

4. Amphotericin B (80 mg/mL) may be used as a rinse.

5. Gentian Violet Solution 1% to 2% may be tried in difficult or recurrent cases.

D. Vulvovaginitis

1. Imidazoles or Triazoles are the first-line drugs. Fluconazole has the least potential for drug interactions and is considered the least toxic.

2. Resistance to Therapy may be due to infection with nonalbicans strains such as Candida glabrata and Candida tropicalis.

3. Topical Therapies

a. Imidazole compounds are effective and are available in a wide array of formulations: 500 mg clotrimazole vaginal tablet as a single dose (Gyne-Lotrimin), 200 mg miconazole tablet at bedtime for 3 days (Monistat-3), 100 mg vaginal tablet or suppository at bedtime for 7 days (Gyne-Lotrimin, Mycelex, Monistat-7), 2% butoconazole (Gynazole, Femstat) or miconazole (Monistat-7) cream daily at bedtime for 3 to 7 days, or 1% miconazole cream for 7 to 14 days (Gyne-Lotrimin, Mycelex). Prophylactic treatment may be helpful in chronic infection. Miconazole is pregnancy category C and clotrimazole is a category B medication.

b. Terconazole (Terazol) is a fungicidal triazole topical preparation effective against many Candida strains. It is used as either a 3-day or a 7-day course (Terazol 7—0.4% cream for 7 days, or Terazol 3—0.8% cream for 3 days). Terconazole is pregnancy category C and is not recommended for use during the first trimester.

c. Nystatin Vaginal Suppositories (100,000 units) may be slightly less effective. They are dosed twice daily for 7 to 14 days and then nightly for an additional 2 to 3 weeks. Topical nystatin is pregnancy category A.

d. Boric Acid, 600 mg in a gelatin capsule, used intravaginally daily for 14 days has been reported effective even in resistant Candida infections. It may cause local irritation or toxicity from systemic absorption.

e. In Severe or Very Symptomatic Candida Vulvitis, a topical corticosteroid for the first 3 to 4 days may be used.

4. Systemic Therapies

a. A Single Oral Dose of 150 mg of fluconazole has been U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Its efficacy is equivalent to topical therapy and to

oral itraconazole 200 mg at two doses 12 hours apart.8 Slightly greater efficacy may be achieved with fluconazole 100 mg/day for 5 to 7 days or itraconazole 200 mg/day for 3 to 5 days.9

oral itraconazole 200 mg at two doses 12 hours apart.8 Slightly greater efficacy may be achieved with fluconazole 100 mg/day for 5 to 7 days or itraconazole 200 mg/day for 3 to 5 days.9

b. In a randomized controlled trial, neither oral nor intravaginal use of yogurt-containing Lactobacillus acidophilus was shown to decrease candidal infection.10

c. Recurrent infection is defined as greater than three episodes per year in the absence of antibiotic use. Prophylactic regimens include clotrimazole (Gyne-Lotrimin) two 100-mg tablets intravaginally BIW, terconazole (Terazol) 0.8% cream one applicator per week, and fluconazole (Diflucan) 150 mg PO each week.11

In addition to treating the Candida infection, it is important to address predisposing medical conditions and physical factors. Diabetic patients must pay attention to blood sugar levels. Those patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis should avoid spermicide. As with all conditions, a careful history and physical examination must be performed.

ONYCHOMYCOSIS

I. BACKGROUND

Onychomycosis, or fungal infection of the nails, is seen in approximately 6% to 8% of the adult population, and in 40% of patients with fungal infections in other locations. It is the most common nail disorder, accounting for approximately half of all nail abnormalities. Clinical subtypes of infection include distal lateral subungual, proximal subungual, white superficial, and candidal onychomycosis. Risk factors for dermatophyte infections include aging, humid or moist environments, psoriasis, tinea pedis, injured or damaged nails, and immunocompromised states. Fingernails are less commonly involved than toenails. Dermatophytes such as Trichophyton species, Epidermophyton, and Microsporum are the most common causes of onychomycosis; however, Candida and nondermatophyte molds such as Scopulariopsis brevicaulis, Fusarium sp., Acremonium, and Aspergillus species can also cause infection.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

In onychomycosis, nails become brittle, friable, and thickened (Fig. 16-6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree