25 Fat grafting to the breast

Synopsis

Autologous fat is a reconstructive workhorse when it comes to correcting mild to moderate contour deformities in reconstructed breasts.

Autologous fat is a reconstructive workhorse when it comes to correcting mild to moderate contour deformities in reconstructed breasts.

Fat grafting may be used safely for a variety of reconstructive indications. A variety of specific harvesting and processing techniques are available that are effective and techniques continue to evolve.

Fat grafting may be used safely for a variety of reconstructive indications. A variety of specific harvesting and processing techniques are available that are effective and techniques continue to evolve.

Fat grafting for breast augmentation is effective, but its precise role in the cosmetic plastic surgeon’s armamentarium is yet to be defined.

Fat grafting for breast augmentation is effective, but its precise role in the cosmetic plastic surgeon’s armamentarium is yet to be defined.

Fat grafting to the breast is very effective at correcting commonly-encountered contour deformities.

Fat grafting to the breast is very effective at correcting commonly-encountered contour deformities.

Fat grafting to the breast is becoming more accepted by mainstream practitioners as familiarity increases with techniques and potential complications, but it remains controversial for some indications

Fat grafting to the breast is becoming more accepted by mainstream practitioners as familiarity increases with techniques and potential complications, but it remains controversial for some indications

Complications are minor and infrequent if a proper technique is followed.

Complications are minor and infrequent if a proper technique is followed.

External pre-expansion and adipose-derived stem cells hold promise for future enhancement of the results and treatment of difficult problems.

External pre-expansion and adipose-derived stem cells hold promise for future enhancement of the results and treatment of difficult problems.

Introduction

Autologous fat grafting to the female breast has a long history surrounded by a great deal of controversy but relatively little scientific data, until recently.1–10 Despite the paucity of high-quality published evidence and continued disagreement about the best technique, autologous lipofilling to the female breast will continue to evolve because it makes sense and it works! Like many fundamentally good ideas in plastic surgery, the concept is elegant in its simplicity: fat is removed from a location where it is not needed and used to augment body contour in an area of need or desire. To be compelling for the average practitioner, the procedure must have a reliable technique and not subject either the donor or recipient site to unacceptable risk.

This chapter will examine the current use of autologous fat grafting of the breast for a variety of indications, including filling contour irregularities and supplementing other forms of breast reconstruction after mastectomy in both the radiated and nonradiated breast. Another indication is correcting divots and other contour deficits after breast conservation therapy which included radiation treatment. Autologous fat has been used for reconstruction of the entire breast after mastectomy without requiring either an implant or a flap.11 Fat grafting has also been described for correcting congenital anomalies of the breast such as Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, and thoracic hypoplasia. Similarly, autologous fat can be used to correct acquired deformities of the breast other than after cancer treatment, such as might occur after previous implants or other breast surgery. The chapter concludes with an analysis of the controversy surrounding the use of autologous fat grafts for primary breast augmentation.2,7,12–16

In 2005, we reported on the use of autologous fat grafting to correct contour deformities in the reconstructed breasts of 37 patients.1 Most of the 47 treated breasts (85%) experienced worthwhile improvement from the procedure, and only 8.5% of the treated breasts experienced a significant complication (one cellulitis and three cases of fat necrosis). Based on these results, we recommended fat injection as a “safe and effective tool for improving the cosmetic result of either autologous or implant breast reconstruction”.

More recently, other retrospective reviews have found similarly good results and low complication rates. In a 2007 retrospective review by Missana et al.,3 of 74 reconstructed breasts treated with fat grafting, the authors found good–excellent results in 86.5% and moderately–good results in an additional 13.5%. Their only complications were five cases of fat necrosis. In 2009, Kanchwala et al.6 reported on fat grafting to 110 breast reconstruction patients, finding good–excellent results in 85% and reporting no complications other than “minor contour irregularities.” Reporting in 2009 on 880 patients treated over 10 years for a variety of reconstructive and cosmetic breast concerns, Delay et al.7 noted good–excellent results in the vast majority of patients with complications, including a 3% rate of fat necrosis and less than 1% infection. None of these review articles found any correlation of fat grafting with the development of a new or recurrent breast cancer, and mammographic abnormalities were confined to calcifications that were easy for experienced radiologists to distinguish from neoplastic patterns of calcification.

An understanding of the effective use of fat grafting in principle is fundamental to the use of fat grafting for any indication. For this reason, this chapter will include a detailed discussion of the treatment of generic contour deformities of the breast for which fat grafting is indicated. Contour deformities after reconstructive breast surgery for mastectomy are relatively common, and autologous fat has become a workhorse to correct them because of its relative simplicity, low cost, and lasting results.1,2,7 We advise the surgeon to achieve success at fat grafting for these indications, prior to considering its use in the more controversial areas of lumpectomy deformities or cosmetic augmentation.

History

Autologous fat grafting was pioneered by European surgeons in the late 1800s,17 with the first documented case in the breast being a lipoma autotransplanted to reconstruct a breast defect, by Czerny in 1895.18 Fat grafting enjoyed intermittent popularity throughout the early 20th century, with Lexer and others reporting on its use in the breast. These investigators also studied the behavior of grafted fat microscopically and developed some practical guidelines to technique, such as volumetric overgrafting to account for resorption. Still, the practice never became popular until the 1980s, when the widespread adoption of liposuction by plastic surgeons resulted in easy access to large volumes of donor fat.

Despite the fact that scarring and calcifications were also known to result from other accepted breast surgical procedures, the previously resurgent use of autologous fat in the breast all but ceased. Its use in the breast continued by a few practitioners who advanced the art without much recognition.19 The practice re-emerged from the shadows only in 2005–2007, when several authors published their experiences, including the potentially restorative effects of adipose-derived stem cells on radiated breast tissues. Since then, there has been renewed interest in the techniques and a blossoming of published reports. An ASPS research task force into autologous fat use in breast and other tissues reported its results in 2009, finding the practice largely safe, but lacking in scientific validation.

Basic science/disease process

Stem cells and radiation deformities

Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) were first described in the 1920s, with early research focusing on which cells survived transplantation and became new host fat cells, which helped to characterize the process and improve the survival of fat grafts. More recently, the regenerative qualities of adipose-derived stem cells on damaged tissue were found, and they have potentially dramatic treatment implications for patients with radiation-induced injury.20 As radiation is increasingly being used in the breast for aggressive indications, the average practitioner can be expected to encounter more and more of these deformities.

Traditionally, little in the reconstructive armamentarium has been able to address the primary problem of tissue damage. Solutions have been centered around replacement techniques: flaps to replace a retracted lumpectomy defect or eliminate an implant with surrounding capsular contracture. The promise of adipose-derived stem cells lies in their ability to reverse the fibrotic changes of radiation damage.20 The future may bring more comprehensive solutions to breast reconstruction, such as ADSC-seeded biomaterial constructs10 and fat grafting, combined with negative pressure external soft-tissue expansion.11 Presently, the use of fat grafting augmented with expanded populations of ADSCs is limited to research institutions, but fat grafts harvested and processed with the traditional techniques may contain some stem cells.

Patient selection

Autologous fat grafting is indicated to restore normal contour in an area of deformity. These deformities occur commonly in breasts reconstructed with flaps or implants and also occur as undesirable sequelae of implants placed for cosmetic breast augmentation (Table 25.1). There follows a discussion on specific indications, with examples of each.

Table 25.1 Specific indications for fat grafting

| Established indications: safe and effective | Effective and probably safea | Safe but not yet proven |

|---|---|---|

| Primary reconstruction as the sole methodc |

aDetailed informed consent and IRB approval required. bBeing evaluated in clinical trials.11,21,22 cBeing evaluated in clinical trials.11

Contour deformity after implant reconstruction

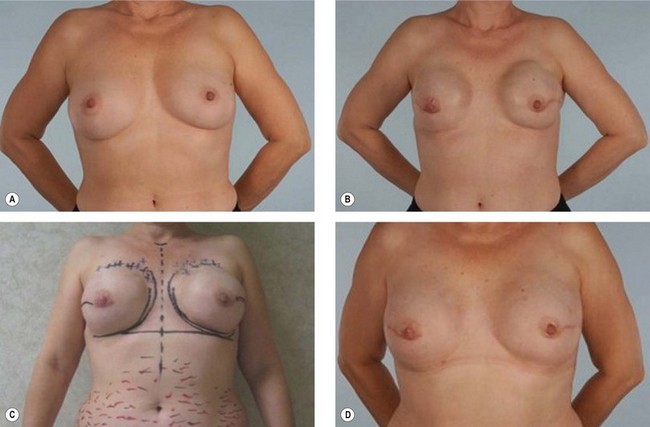

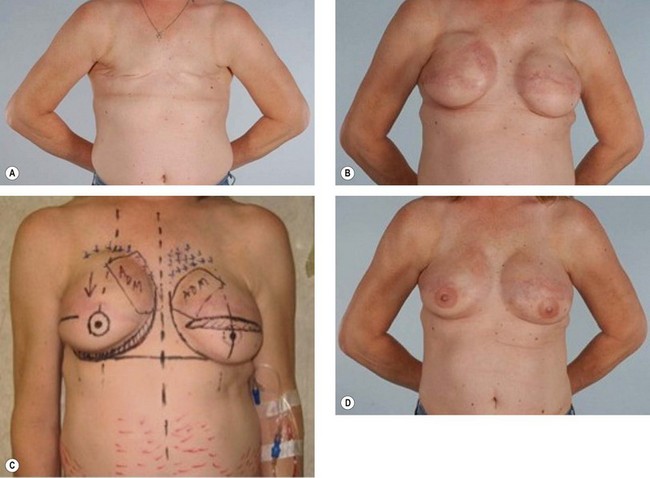

With implant reconstructions, thin overlying tissue can lead to sharp implant borders (Fig. 25.1) and visible rippling (Fig. 25.2), both of which can be effectively softened by fat grafting. These patients are often slender with relatively little subcutaneous fat, or are patients whose mastectomy flaps were left very thin by the breast surgeon. If the implant is very mobile in a large pocket, an unnatural “trench” can form at the interface between the implant and the chest wall. This may be further accentuated medially by lateral shift of the implant when the patient is supine. Such deformities may require a combination of implant exchange to different size, capsulorrhaphy, capsular reinforcement with acellular dermal matrix, and fat grafting (see Fig. 25.4). These deformities are also encountered in the slender cosmetic patient, especially when implants are placed in the subglandular plane.

Contour deformity after flap reconstruction

In the case of flap reconstruction, the border of the flap is a common location for a depression, often occurring as a “step-off” where the flap ends and the normal residual tissue begins.6 Characteristically, this deformity consists of skin flap directly over the chest wall muscle or bone, and reflects the step-off that can occur at the edge of a flap where it is inset to fill a mastectomy defect or from fat necrosis at the vulnerable edges of the reconstructive tissue (Figs 25.3, 25.4). Deformities intrinsic to the flap, such as areas of fat necrosis within the substance of the flap or the periumbilical tissue in a TRAM, are also common indications and may occur within the flap substance or at the borders.

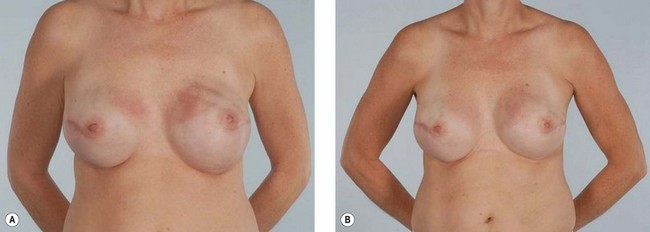

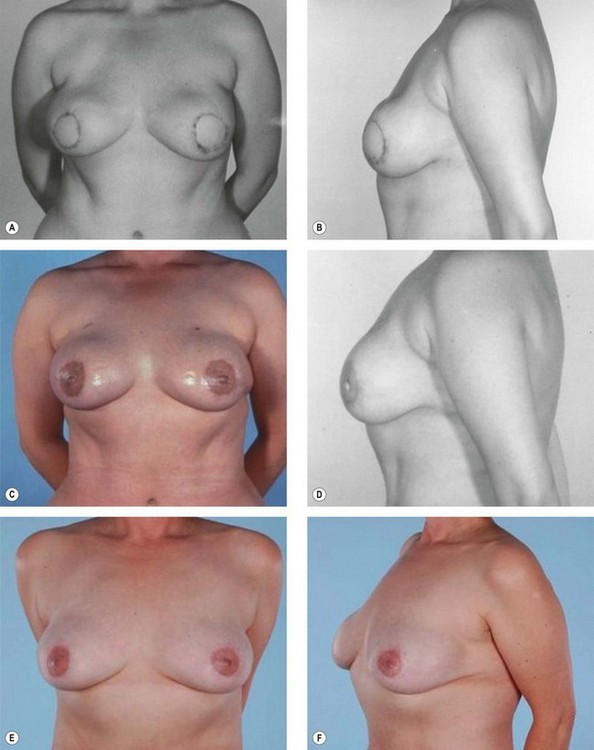

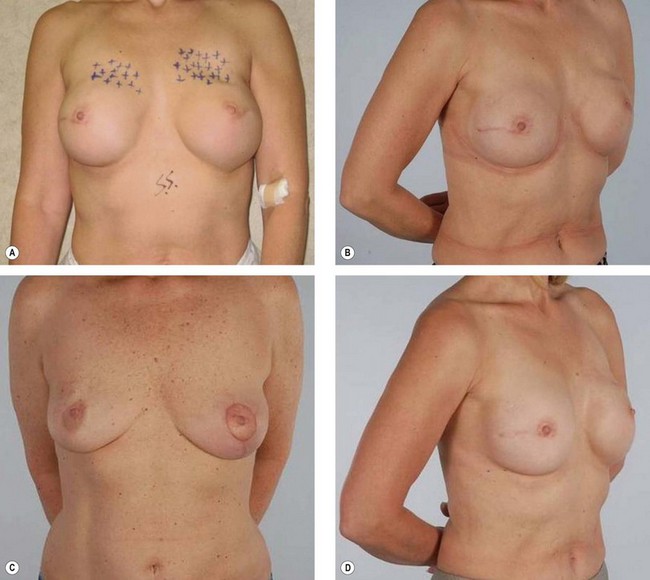

Contour deformities after implant or flap reconstructions in a radiated field

Suitable patients with radiation damage have a breast contour deformity secondary to implant or flap reconstruction after mastectomy, exacerbated by radiation changes such as those described in the radiation section above. These deformities may have components of the above step-off or intrinsic flap deformities, in addition to the tissue fibrosis, skin changes, or capsular contracture brought about by radiation (Figs 25.5, 25.6). The complications of flap reconstructions that are the most difficult to correct tend to occur when the reconstruction was performed prior to the radiation.23 These include volume loss, fat necrosis, delayed wound healing, and fibrosis. While the experience with fat grafting as an adjunct to other breast reconstructions has been largely favorable, the evidence is unclear and unconvincing, when looking specifically at the radiated breast. Radiation introduces added risks, complexities, and problems. The risks include an increased risk of infection and of nonhealing of the surgical site. The complexities include the difficulty of creating space for the fat in a badly radiation-fibrosed recipient site, and the problems are the lack of both skin elasticity and a fertile recipient site conducive for the fat grafts to take.

A review of the literature indicates that experience with fat grafting in the radiated environment has only recently been addressed. The 2007 publication by Rigotti et al. details some cases showing dramatic improvements to both capsular contracture and impending implant exposure as a result of stem-cell enhanced autologous fat grafting.20 In 2009, Delay et al. reported that fat grafting can improve the quality of radiation-damaged post-mastectomy skin contributing to an autologous reconstruction or permitting an implant reconstruction to be used where it may have previously been contraindicated.7 Serra-Renom et al. reported an innovative approach to the reconstruction of radiated mastectomy defects in 2009.24 The authors reported on 65 patients, whom they reconstructed in three stages: tissue expander placement, expander exchange for permanent implant, and nipple reconstruction. At each stage, an average of 150 cc of autologous fat was grafted to enhance the volume of the reconstruction. The authors report excellent results, with no capsular contracture or other complications. They conclude that fat grafting enhanced the reconstruction by improving the skin quality and adding subcutaneous volume to the breasts.

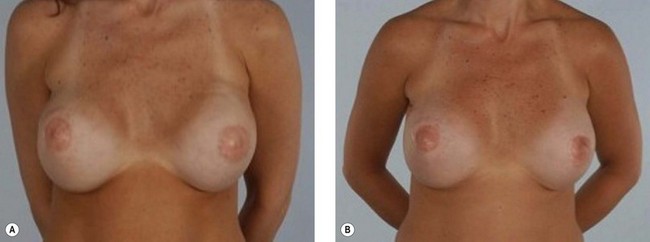

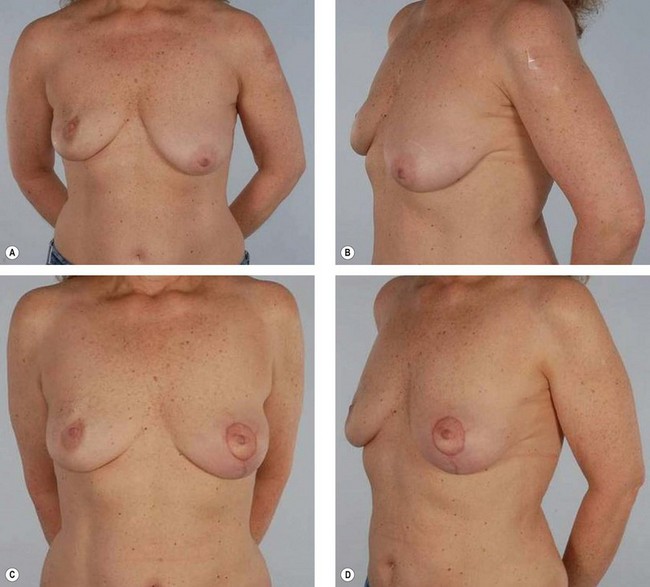

Lumpectomy deformities

Lumpectomy deformities of up to 10–15% of the breast volume often result in satisfactory aesthetic results.25 The actual resected percentage, however, may often be higher with re-excisions or a desire to avoid mastectomy on the part of the patient or breast surgeon. Although oncoplastic techniques may result in very good symmetry if performed at the time of lumpectomy, they are not universally utilized or available. Accordingly, lumpectomy with radiation results in suboptimal aesthetic outcomes of up to 30% (Fig. 25.7).26 The idea of fat grafting these lumpectomy defects is very appealing because no other techniques are appropriate for most of these patients and what is missing is usually all or in part fat. Implants perform badly in a radiated environment, and flaps are often best reserved for total or sub-total mastectomy defects. The problems and challenges however, are similar as for radiation after mastectomy. Fibrosis, risk of infection, and a hostile environment for grafts make the radiated lumpectomy defect an uncertain, unproven application. This is magnified by the heightened concern for monitoring and detecting local breast cancer recurrence in these patients.

There is little in the literature on lumpectomy deformities being reconstructed with autologous fat grafting. In his 2007 publication detailing the use of adipose-derived stem cells, Rigotti published impressive photographs of a patient whose radiated lumpectomy defect was dramatically improved by stem cell-enriched fat injection.20 A 2009 report of experience by Delay et al. on 42 patients indicates that the fat grafting is valuable in the management of moderate deformities resulting from breast conservation.7,27 The authors caution that the medicolegal environment surrounding fat grafting for this indication is treacherous, however, and they use a very strict protocol involving detailed pre- and post-procedure imaging, specially trained radiologists, and management of the patient within a multidisciplinary team. Delay recommends completing the “learning curve” for fat grafting prior to using it to reconstruct radiated lumpectomy defects.7

Congenital deformities

Just as the FDA recognized that certain nonmastectomy problems were surgically comparable with those caused by cancer treatment, we recognize that some congenital and other acquired breast deformities can be and should be treated like those after mastectomy or breast conservation therapy. These include Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, thoracic hypoplasia, tuberous breasts, and major asymmetries. Some of these patients can be treated in whole or in part by other techniques, but fat grafting brings an additional powerful tool to help solve the problem, often where nothing else is practical. This has been shown for the deformity associated with the tuberous breast.2 It has also been demonstrated for chest wall deformities where the upper pole is beyond the reach of the implant.1

Poland syndrome results in absence of the pectoralis muscles and underdevelopment of the breast gland. Provided the latissimus is present, an excellent reconstructive solution involves a latissimus flap with placement of an implant.28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree