2 Facial trauma

Soft tissue injuries

History

Our understanding of the management of maxillofacial injuries is the result of thousands of years of accumulated knowledge and experience by those who came before us. The ancient texts of the Sumerians (5000 bc), and the Egyptians (3500 bc) offer specific advice for the management of a variety of maxillofacial injuries. In particular, they discuss that soft tissue injuries may harbor other deeper injuries to bone or brain and that the surgeon should explore the wound with their finger to feel for these injuries.1,2 The renaissance texts from Europe and Mexico write about the importance of treating life-threatening wounds and not ignoring the restoration of cosmetic appearance: “the wounds of the face … have to be cured with extreme care because the face is a man’s honor.”3 They also understood that infection was uncommon in facial wounds but very common in extremity wounds. Because of this, the usual recommendation for placement of a cotton wick to drain the wounds was not a part of facial wound closure. They also understood that sutures should be removed early to prevent suture marks on the face.

Basic science

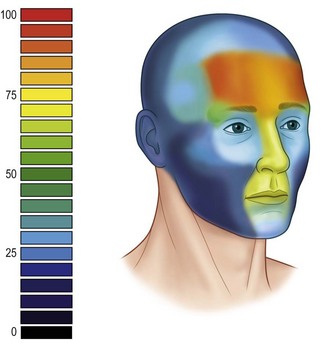

The etiology of facial soft tissue trauma varies considerably depending upon age, sex, and geographic location. Many facial soft tissue injuries are relatively minor and are treated by the emergency department without a referral to a specialist. There are little data regarding the etiology of facial trauma that is subsequently referred to a specialist, but it is weighted towards more significant traumas such as road crashes and assaults. The location of facial soft tissue trauma tends to occur in certain areas of the head depending on the causative mechanism. When taking all etiologies of facial trauma into account, the distribution is concentrated in a “T-shaped” area that includes the forehead, nose, lips and chin. The lateral brows and occiput also have localized frequency increases.4 These areas are more prone to injury because they primarily overlie bony prominences that are at risk from any blow to the face, whether that be an assault, fall, or accident (Fig. 2.1).

Global considerations

Because the face is so well perfused its ability to resist infection is better than other areas of the body. Human bites to the hand treated without antibiotics have approximately a 47% risk of infection,5 whereas if we inadvertently bite our cheeks, lips or tongue we almost never develop an infection. The lower risk of infection in the face has practical applications for management of facial soft tissue injuries. Many a medical student has been told that any wound that has been open for 6 hours cannot be closed primarily. This belief is based on tradition rather that good science. While there is no doubt that the longer a wound is open the more likely it is to become contaminated, there is no magical time cut-off for primary closure.6 Because the face carries such profound cosmetic importance, the small increased risk of infection associated with delayed closure of a wound will be trumped by improved cosmesis associated with primary closure. This author recommends closure of facial wounds at the earliest time possible that will not interfere with the management of other more serious injuries, but do not let time deter you from obtaining primary closure.

Diagnosis and patient presentation

Systematic evaluation of the head and neck

Ear examination

The ears should be inspected for hematomas that will appear as a diffuse swelling under the skin of the auricle (Fig. 2.2). Any lacerations should be noted. Otoscopy should be done to look for lacerations or the auditory canal, tympanic membrane injuries, or hemotympanum.

Cheek examination

Any laceration of the cheek that is near any facial nerve branch or along the course of the parotid duct will need to be investigated. Asking the patient to raise their eyebrows, close their eyes tight, show their teeth or smile while looking for asymmetry or lack of movement will reveal any facial nerve injury. An imaginary line connecting the tragus to the central aspect of the philtrum defines the course of the parotid duct (Fig. 2.3). The duct is at risk from any injury in the central third of this line. If you are unsure about a duct injury, Stensen’s duct should be cannulated and fluid instilled to see if it leaks out of the wound.

Neck examination

The first priority when evaluating a soft tissue injury to the neck is evaluation of the airway. You should be concerned about the patient’s airway if they have garbled speech, dysphonia, hoarseness, persistent oropharyngeal bleeding, or if they appear agitated or struggling for air.7 Once the airway is secured, and the exam shows no compromise, the soft tissue injury should be examined with adequate light and suction to rule out penetration deep to the platysma. If the soft tissue injury penetrates through the platysma then the trauma surgeons must be consulted to evaluate a penetrating neck injury.

Treatment and surgical techniques

Anesthesia for treatment

Topical

Topical anesthetics are well established for the treatment of children with superficial facial wounds and to decrease the pain of injection. The most widely used topical agent is a 5% eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) containing lidocaine and prilocaine.8,9 EMLA has been shown to provide adequate anesthesia for split thickness skin grafting,10 and minor surgical procedures such as excisional biopsy and electrosurgery.11 Successful use of EMLA requires 60–90 min of application for adequate anesthesia. The most common mistake leading to failure is not allowing sufficient time for diffusion and anesthesia. Some areas such as the face with a thinner stratum corneum may have onset of anesthesia more quickly.

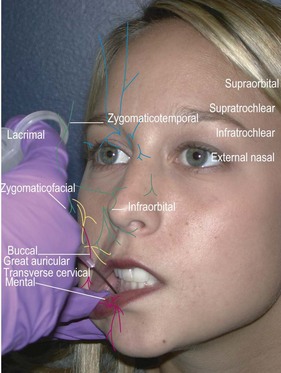

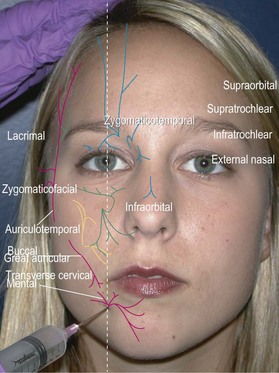

Facial field block

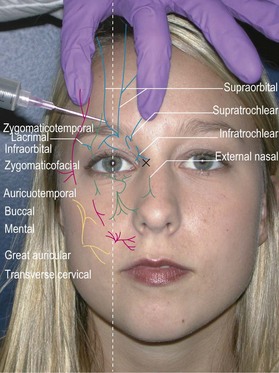

Forehead, anterior scalp to vertex, upper eyelids, glabella (supraorbital, supratrochlear, infratrochlear nerves)

Method: Identify the supraorbital foramen or notch along the superior orbital rim and enter just lateral to that point. Direct the needle medially and advance to just medial of the medial canthus (about 2 cm). Inject 2 cc while withdrawing the needle (Fig. 2.4).12

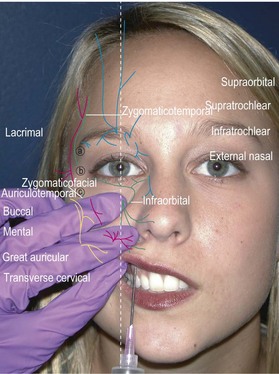

Lateral nose, upper lip, upper teeth, lower eyelid, most of medial cheek (infraorbital nerve)

Method: Identify the infraorbital foramen along the inferior orbital rim by palpation. An intraoral approach is better tolerated and less painful (Fig. 2.5). Place the long finger of the nondominant hand on the foramen and retract the upper lip with thumb and index finger. Insert the needle in the superior gingival buccal sulcus above the canine tooth root and direct the needle towards your long finger while injecting 2 cc. You may also inject percutaneously by identifying the infraorbital foramen about 1 cm below the orbital rim just medial to the mid-pupillary line. Enter perpendicular to the skin, advance the needle to the maxilla, and inject about 2 cc (Fig. 2.6).12

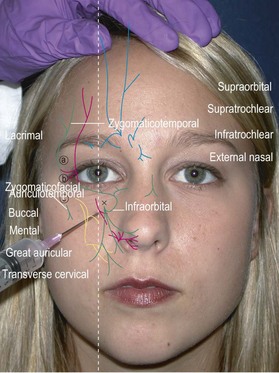

Lower lip and chin (mental nerve)

Method: The lower lip is retracted with the thumb and finger of the nondominant hand and the needle inserted at the apex of the second premolar. The needle is advanced 5–8 mm and 2 cc are injected (Fig. 2.7). When using the percutaneous approach, insert the needle at the mid-point of a line between the oral commissure and inferior mandibular border. Advance the needle to the mandible and inject 2 cc while slightly withdrawing the needle (Fig. 2.8).12

Posterior auricle, angle of the jaw, anterior neck (cervical plexus: great auricular, transverse cervical)

Method: Locate Erb’s point by having the patient flex against resistance. Mark the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and locate the midpoint between clavicle and mastoid. Insert the needle about 1 cm superior to Erb’s point and inject transversely across the surface of the muscle towards the anterior border. A second more vertically oriented injection may be needed to block the transverse cervical nerve.12

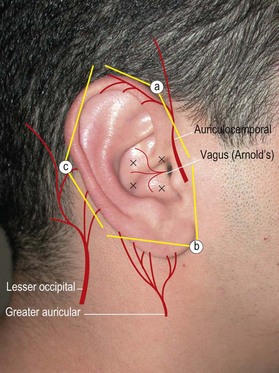

Ear (auriculotemporal nerve, great auricular nerve, lesser occipital nerve, and auditory branch of the vagus (Arnold’s) nerve)

Method: Insert a 1.5 inch needle at the junction of the earlobe and head and advance subcutaneously towards the tragus while infiltrating 2–3 cc of anesthetic (Fig. 2.9). Pull back the needle and redirect posteriorly along the posterior auricular sulcus again injecting 2–3 cc. Reinsert the needle at the superior junction of the ear and the head. Direct the needle along the preauricular sulcus towards the tragus and inject 2–3 cc. Pull back and redirect the needle along the posterior auricular sulcus while injecting. It may be necessary to insert the needle a third time along the posterior sulcus to complete a ring block. Care should be taken to avoid the temporal artery when directing the needle along the preauricular sulcus. If the artery is inadvertently punctured, apply pressure for 10 min to prevent formation of a hematoma.

General treatment considerations

Abrasions

Abrasions result from tangential trauma that removes the epithelium and a portion of the dermis leaving a partial thickness injury that is quite painful. This type of injury is often the result of sliding across pavement or dirt and therefore embeds small particulate debris within the dermis. If dirt and debris are not promptly removed the dermis and epithelium will grow over the particulates and create a traumatic tattoo that is very difficult to manage later. Topical anesthetics, if properly applied and given sufficient time for onset, can give good anesthesia for cleansing of simple abrasions. This can be accomplished with generous irrigation and cleansing with a surgical scrub brush (Fig. 2.10). If more involved debridement is needed general anesthesia is advisable.

Traumatic tattoo

Abrasive traumatic tattoos are more common. Typically, a person is ejected from a vehicle, or thrown from a bicycle and subsequently grinds their face into the pavement. This causes a simultaneous traumatic dermabrasion of the epidermis and superficial dermis, and embedding of the pigment (dirt). If left untreated, the dermis and epidermis heal over the pigment resulting in a permanent tattoo (Fig. 2.11).

Regardless of the mechanism of injury, prompt removal of the particulate matter results in a far better outcome than later removal. Once the skin has healed the opportunity to remove the particles with simple irrigation and scrubbing is lost. The initial treatment is vigorous scrubbing with a surgical scrub brush or gauze and copious irrigation.13–17 Wounds treated within 24 hours show substantially better cosmetic outcome than those treated later,15 however some improvement has been seen as late as 10 days.18 Larger particles should be searched for and removed individually with fine forceps or needles, loupe magnification, and generous irrigation.19 The tedious and time consuming nature of this procedure may require serial procedures over several days to complete, nonetheless meticulous debridement of the acute injury is the best opportunity for optimal outcome.

The treatment of a traumatic tattoo remains an unresolved problem in plastic surgery, and as such, there are multiplicities of techniques, none of which are perfect. Some of the treatment options include surgical excision and microsurgical planning,20,21 dermabrasion,22–25 salabrasion,26 application of various solvents such as, diethyl ether,16 cryosurgery, electrosurgery, and laser treatment with carbon dioxide, argon lasers,13,14,16,27 Q-switched Nd:YAG laser,28,29 erbium-YAG laser,30 Q-switched alexandrite laser,31,32 and Q-switched ruby laser.33,34 The mechanism for laser removal is not entirely understood but is thought to involve the fragmentation of pigment particles, rupture of pigment containing cells, and subsequent phagocytosis of the tattoo pigment.35,36 Laser therapy for pigment tattoos will require slightly higher fluencies than those used for removal of professional tattoos.33

A note of caution is in order when treating gunpowder traumatic tattoos. Several authors have noted ignition of retained gunpowder during laser tattoo removal,29,37 resulting in spreading of the tattoo or creation of significant dermal pits. If initial laser treatment suggests the presence of un-ignited gunpowder in the dermis, laser removal should be discontinued in favor of other treatments such as dermabrasion or surgical micro-excision of the larger particles.

Simple lacerations

Sharp objects cutting the tissue usually cause simple or “clean” lacerations. Lacerations from window and automobile glass, or knife wounds are typical examples (Fig. 2.12). Simple lacerations may be repaired primarily after irrigation and minimal debridement, even if the patient’s condition has delayed closure for several days. When immediate closure is not feasible, the wound should be irrigated and kept moist with a saline and gauze dressing. Prior to repair, foreign bodies such as window glass should be removed. Wounds of this type usually require little or no debridement. A few well placed absorbable 4-0 or 5-0 sutures will help align the tissue and relieve tension on the skin closure. The temptation to place numerous dermal sutures should be avoided because excess suture material in the wound will only serve to incite inflammation and impair healing. The skin should be closed with 5-0 or 6-0 nylon interrupted or running sutures; alternatively, 5-0 nylon or monofilament absorbable running subcuticular pullout sutures can be placed. Any suture that traverses the epidermis should be removed from the face in 4–5 days. If sutures are left in place longer than this epithelization of the suture tracts will lead to permanent suture marks know as “railroad tracks”. Sutures of the scalp may be left in place for 7–10 days. Pullout sutures should usually be removed following the same guidelines, however there less risk of permanent suture marks.

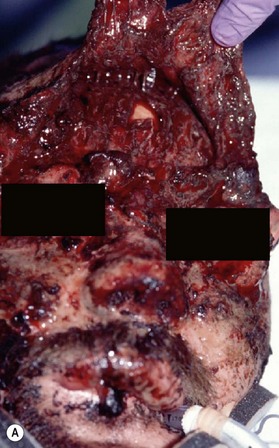

Complex lacerations

When soft tissue is compressed between a bony prominence and an object, it will burst or fracture resulting in a complex laceration pattern and significant contusion of the tissue. Typical examples of these types of lacerations are a brow laceration sustained when a toddler falls onto a coffee table, or an occupant is ejected from a vehicle in a crash striking an object (Fig. 2.13). Many wounds on first impression suggest that there is significant tissue loss, however after irrigation, minimal debridement, and careful replacement of the tissue fragments piece by piece it becomes apparent that most of the tissue is present (Fig. 2.14). Contused and clearly nonviable tissue should be debrided. Tissue that is contused, but has potential to survive should usually be returned to anatomic position. Elaborate repositioning of tissue with Z-plasties and the like should usually be reserved for secondary reconstructions after primary healing has finished. Limited undermining may be used to decrease tension and achieve closure, however wide undermining is rarely indicated. It is probably better to accept a modest area of secondary intention healing and plan for later scar revision rather than risk tissue necrosis from overzealous undermining of already injured tissue.

Secondary intention healing

Some wounds with tissue loss may be best treated by secondary intention healing rather than a more complex reconstruction. The advantages of secondary intention treatment are that it is simple, it does not require an operation, the wound contraction can work to the patient’s advantage, and in certain situations, the cosmetic result can rival other methods of closure. The best cosmetic results are obtained on concave surfaces of the Nose, Eye, Ear and Temple (NEET areas), and those on the convex surfaces of the Nose, Oral lips, Cheeks and chin, and Helix of the ear (NOCH areas) often heal with a poor quality scar. Most wounds can be dressed with a semi-occlusive dressing, or petrolatum ointment to prevent desiccation. Common complications include: pigmentation changes, unstable scar, excessive granulation, pain, dysesthesias, and wound contracture.38,39

Treatment of specific areas

Scalp

The thickness of the skin of the scalp ranges from 3 to 8 mm making it some of the thickest on the body.40 The galea is a strong relatively inelastic layer that is an important structure in repair of scalp wounds. It plays a role in protecting the skull and pericranium from superficial subcutaneous infections, provides a strength layer when suturing, and limits elastic deformation of the scalp often making closure more difficult.

The subgaleal fascia is a thin loose areolar connective tissue that lies between the galea and the pericranium and allows scalp mobility. The emissary veins cross this space as they drain the scalp into the intracranial venous sinuses. This is a potential site of ingress for bacteria contained within a subgaleal abscess leading to meningitis or septic venous sinus thrombosis although the incidence is very low.41–44

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree