CHAPTER 17 Facial rejuvenation in non-Caucasians

History

The culture of beauty is universal and dynamic. It is expressed in different ways in different parts of the world and in different periods of history. The concept of beauty itself has eluded a precise definition and has defied attempts to quantify it. Commonly published canons of facial proportions usually represent Greco-Roman standards and are not applicable to non-Caucasians. Strict adherence to these norms is therefore not necessary to obtain satisfying results in the non-Caucasian.

Census estimates show significant and continuing increases in the ethnic populations in the USA. Minorities are expected to constitute the majority of the USA population by the year 2050.1 The growing population, in concert with the increasing acceptance of plastic surgery, makes the minorities an important factor in the expansion of plastic surgery for years to come, and a segment that deserves our attention. The volume of cosmetic surgical and non-surgical procedures among ethnic minorities constituted 22% of all procedures in 2006.2

Anatomy and physiology of aging

While most of the signs of aging of the face are the result of ultra-violet exposure, the pathogenesis of aging is multi-factorial. They include heredity, the effects of hormonal changes, the weakening of false retaining ligaments, gravitational descent of skin, fat and muscles, decreasing function and content of glandular tissue and skeletal resorption. Progressive photodamage to the epidermis and dermis results, initially, in loss of luster, then dryness, followed by fine rhytids and dyschromia. Histologically, there is thinning of the dermis. The collagen becomes fragile and disorganized and there is quantitative decrease in elastin and fibroblast content.3

Aging in the African-American and Hispanic

The African-American originates from three ethnic groups4: Africans of West and Central Africa, North European Caucasian and American and Caribbean Indians. Various permutations and combinations of the features unique to the three groups abound in the African-American community. The spectrum therefore, includes African-Americans that are almost indistinguishable from Caucasians (Fig. 17.1), to African-Americans that look mostly African or Indian and therefore age accordingly. Hispanics in the USA, to a lesser degree, show a similar spectrum. The notion of aging of African-Americans and Hispanics must therefore be nuanced, taking into account not only these differences in ethnic content but also the effects of gravity, skeletal resorption, glandular atrophy and hormonal changes, which are not dependent on race.

Differences in hair structure between Blacks and other ethnic groups have been documented.5 These include the flat elliptical shape of the follicles and the spiraled, thinner hair shafts. The spiral shape leads to trichonodosis and brittle hair, by impairing transmission of sebum down the shaft. The ellipsoid shape of the follicles predisposes this population to in-grown hairs and therefore pseudofolliculitis barbae which are a source of much distress to many young African-Americans and Hispanic males.

Upper face

One of the earliest signs of aging in the African-American and the Hispanics is frontal and temporal alopecia, which starts as early as the third decade.6 African-Americans males are affected more commonly than females (Fig. 17.2). Hispanics are affected less often than African-Americans. This phenomenon is further accelerated by traction from the popular practice of hair braiding.

However, the complaints that most commonly bring the patients to the plastic surgeon are centered around the brows and periorbital areas. Brow ptosis is a prominent sign of aging occurring a decade or more later than in Caucasians. Descent of the brow often leads to pseudo-dermatochalasis of the upper eyelids.7 Atrophy and graying of the brow hair exacerbates the look of advanced age.

Midface

Aging around the periorbita includes excess skin, pseudo-herniation of fat of upper and lower eyelids, lower lid fine rhytids and periorbital hyperpigmentation. Lateral upper lid fullness due to herniation of the lacrimal glands may occur. The tarsus in the upper eyelid of the African-American is shorter, measuring 5 to 8 mm.6 the supratarsal fold may therefore be located 6 to 8 mm from the lid margin contributing to apparent fullness of the upper eyelid.

Proptosis and scleral show are commonly seen in the African-American and Hispanic, as the aging process advances. Contributing factors include malar hypoplasia and the not uncommon lower position of the lower lid margin.6 Progression of aging around the orbit results in lid laxity and blunting of the lateral canthus. Infraorbital hollowing and tear trough deepening are frequent and early signs of aging as is infraorbital dark pigmentation.

Lower face

Chin atrophy leads to chin wrinkling, marionette lines and down-turning of the commissures (Fig. 17.3). Bimaxillary-prognathism is more commonly seen in the African-American population8. This becomes even more pronounced as soft tissue atrophy occurs. Upper and lower lip protrusion and lower lip eversion are not uncommon in aging African-Americans and darker skinned Hispanics. With advancing age, perioral wrinkles appear.

Evaluation

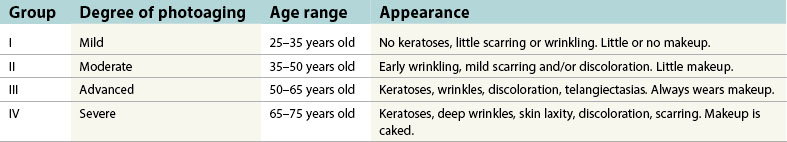

Physical examination should take into account the patterns of aging peculiar of these populations. Skin classification using both the Fitzpatrick (Table 17.1) and the Glogau (Table 17.2) classifications to determine skin type and extent of actinic damage, is essential.

Table 17.1 Fitzpatrick skin type classification

| Skin type | Reaction to sun | Skin color |

|---|---|---|

| I | Always burns | Very white or freckled |

| II | Usually burns, difficulty tanning | White |

| III | Tans, sometimes burns | White to olive |

| IV | Tans easily, rarely burns | Olive to brown |

| V | Very rarely burns | Dark brown |

| VI | Never burns | Black |

Facial rejuvenation

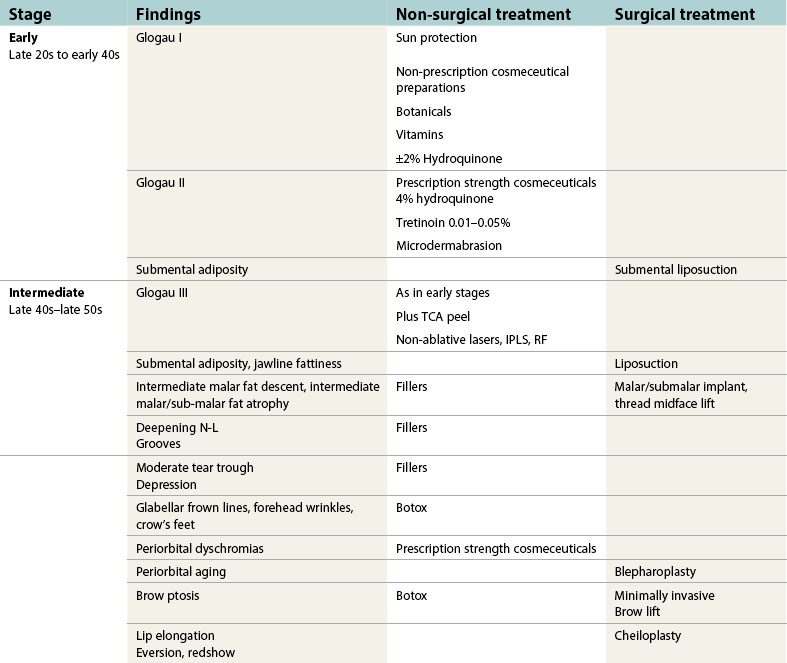

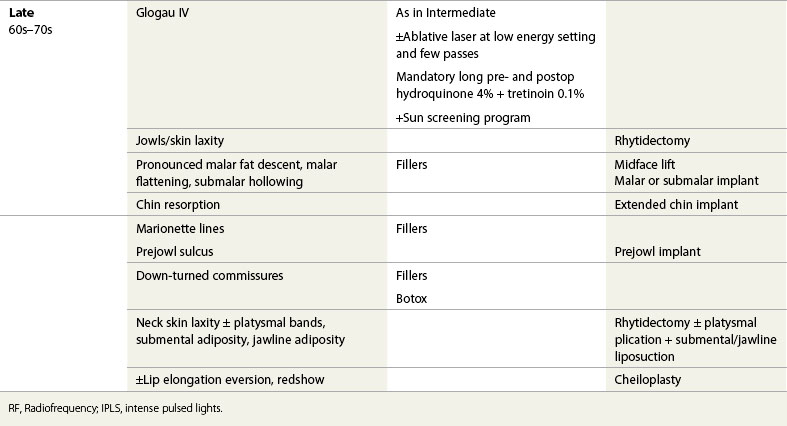

Over the years, with greater understanding of the aging process, our approach to facial rejuvenation has shifted from operative to comprehensive management (Table 17.3). We believe that it is the surgeon’s responsibility not only to offer the most appropriate surgical treatment but also to assume a primary role in educating these patients on the pathology of photo-aging and the need for preventive measures, especially in light of the prevalent myth that dark skin protects them from sun damage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree