Introduction

The facial nerve has a complex course from the brainstem to the periphery. The nerve crosses critical and frequently accessed surgical structures in cranial-base surgery, otoneurologic surgery, head and neck surgery, and cosmetic surgery. During transtemporal approaches, the surgeon has to drill the temporal bone to avoid injury to the facial nerve. When performing approaches to the regions involving the facial nerve, it is mandatory to understand the topographic anatomy of the facial nerve from different surgical perspectives. This chapter provides an overview of the facial nerve from the brainstem through the temporal bone. The extratemporal course of the facial nerve is presented in Chapter 9. All portions and segments of the facial nerve, its blood supply, surrounding structures, radiologic anatomy, and relation to typical surgical approaches are presented in detail to guide the surgical management of this important structure.

Segments of the Facial Nerve

Because of the intricate course of the facial nerve from the brainstem to the periphery, the course is divided into three different portions. Topographically, the portions of the facial nerve are divided into segments. The portions and segments are summarized in Table 8.1. The facial nerve is composed of branchiomotor, parasympathetic, visceroafferent, and somatic-efferent fibers. Facial-nerve branches with different fiber qualities are leaving or entering the nerve during its course to the periphery. The facial nerve has internal branches leaving and entering the nerve in the temporal bone, and all external branches leave the nerve after its exit from the stylomastoid foramen.1 Table 8.2 gives an overview of the facial nerve branches.

Intracranial Portion

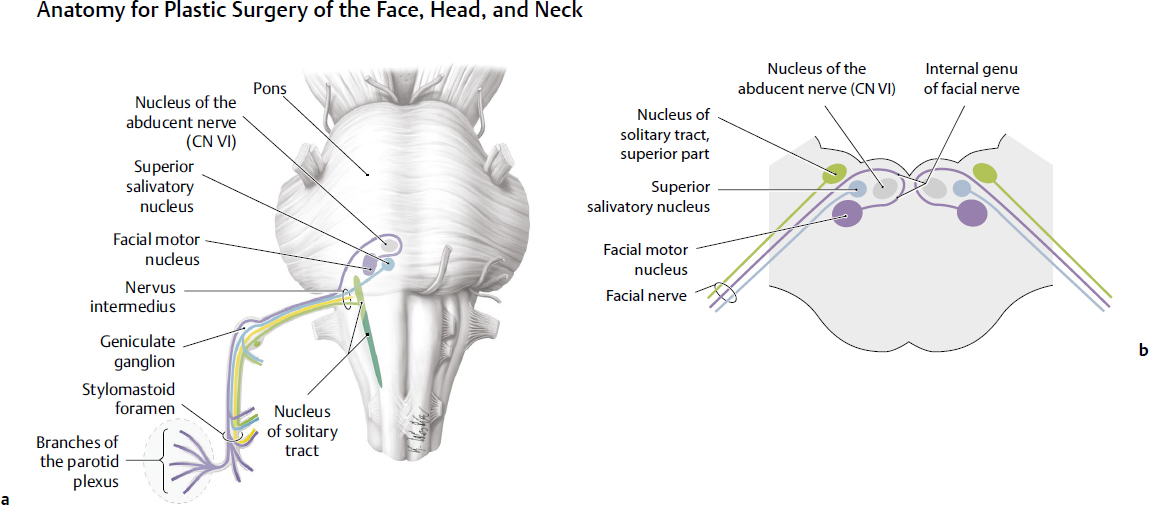

Three primary brainstem nuclei contribute to the function of the facial nerve: (1) the facial motor nucleus for somatic motor function (in a stricter sense, the facial nerve is an exclusive motor nerve), (2) the superior salivatory nucleus for secretomotor (autonomic) function, and (3) the nucleus of the tractus solitarius for taste. All three nuclei are located in the brainstem (Fig. 8.1): (1) the facial motor nucleus in the lower third of the pons in the floor of the fourth ventricle, (2) the superficial salivary nucleus directly next to the facial motor nucleus, and (3) the nucleus of the tractus solitarius lateral to the dorsal vagus nucleus in the medulla oblongata. It is important, when treating a patient with a brainstem lesion and facial palsy, to differentiate the localization of the nuclei of the facial nerve. Depending on the lesion site, the patient can have a supranuclear, nuclear, or infranuclear (peripheral) facial-nerve palsy or a combined lesion; this consideration is important in the prognosis of the palsy and valuable in planning facial-nerve reconstruction surgery. Moreover, a lesion of the superior salivatory nucleus or of the nucleus of tractus solitarius can explain nonmotor deficits of the patient related to the facial nerve.

Medullary Segment

The facial motor nucleus contains the facial motoneuron soma, the axons of which form the facial motor nerve. Here the medullary segment begins. The axons leave the nucleus first in a dorsomedial direction, pass around the nucleus of the abducens nerve to form the internal facial genu (knee) (cf. Fig. 8.1b), and leave the brainstem from the anterior pons lateral to the abducens nerve and medial to the vestibulocochlear nerve. The facial motor nerve is joined by the intermediate nervus (nervus intermedius, nerve of Wrisberg) containing sensory and parasympathetic fibers. The parasympathetic fibers of the nervus intermedius arise from the salivatory nuclei, and the taste fibers terminate in the nucleus tractus solitarius. The nervus intermedius is lateral to the facial motor nerve when both leave the brainstem in the cerebellopontine angle (CPA). The medullary segment of the facial nerve ends here, and the cisternal segment begins.

Cisternal Segment

Within the CPA cistern, the facial nerve is most anterior and superior, the vestibulocochlear nerve most posterior, and the nervus intermedius—giving the nerve its name—between the two. This is important when orientating for vestibular schwannoma surgery or facial-nerve repair should be performed in the CPA. The cisternal segment ends when the facial nerve enters the porus acusticus of the internal acoustic meatus. The facial nerve and the nervus intermedius resemble the nerve roots of the spinal cord within the cistern.2

Table 8.1 Classification of the course of the facial nerve

Portion/segment | Length (mm) |

Intracranial portion |

|

Medullary segment | 3.5–6 |

Cisternal segment | 18–21 |

Intratemporal portion |

|

Meatal segment | 8–12 |

Labyrinthine Segment | 3–5 |

Geniculate ganglion segment | 3–3 |

Tympanic segment | 8–11 |

Mastoid segment | 13–14 |

Extratemporal portion (see Chapter 9 for details) | 15–20 |

Intratemporal Portion

Meatal Segment

The facial nerve enters the temporal bone via the internal acoustic meatus. The meatal segment is congruent with the internal acoustic meatus. The facial and vestibulocochlear nerves pass through the internal acoustic meatus on the posteromedial surface of the petrous ridge. The facial nerve is joined by the nervus intermedius. Both are located in the anterior superior quadrant of the internal acoustic meatus above the falciform crest and anterior to Bill’s bar. These are important landmarks when approaching the facial nerve via a translabyrinthine, transcochlear, or middle cranial fossa approach.

Labyrinthine Segment

As the facial nerve enters the fallopian canal, the labyrinthine segment begins (Fig. 8.2). The fallopian canal houses the labyrinthine, tympanic, and mastoid segments. The nerve takes an anterolateral course between and superior to the cochlea (anterior) and vestibule (posterior). Then the nerve turns back posteriorly at the geniculate ganglion. The labyrinthine segment is short and is the narrowest segment. The facial nerve occupies up to 83% of the labyrinthine canal cross-sectional area compared with only 64% of the more distal mastoid segment.3 Therefore, it is said that the labyrinthine segment is especially susceptible to vascular compression, which might play a role in treating patients with idiopathic facial palsy (Bell’s palsy).

Geniculate Ganglion Segment

The geniculate ganglion segment is equated to the geniculate ganglion (Fig. 8.3, Fig. 8.4). Some authorities include the geniculate ganglion with the labyrinthine segment. Following this definition, the geniculate ganglion would reside within the distal part of the labyrinthine segment. The ganglion consists of first-order pseudounipolar nerve cells related to taste sensation from the anterior tongue via the chorda tympani and the greater petrosal nerve. The latter reaches the ganglion from the greater petrosal canal. At the ganglion, the nerve has to bend down to reach the tympanic segment; this bend is called the external genu.

Tympanic Segment

After the geniculate ganglion, the nerve becomes the tympanic segment. The junction to the tympanic segment is formed by an acute angle, and shearing of the facial nerve commonly occurs as the nerve traverses this genu.4 The facial nerve runs posteriorly beneath the lateral semicircular canal in the medial wall of the middle ear cavity (Fig. 8.5). The fallopian canal is often dehiscent, especially in the area near the oval window.5 This is important during middle ear surgery because the absent bony protection can allow for direct invasion of the facial nerve by chronic infection and because the nerve is at greater risk for iatrogenic injury in such situations. Duplication of the facial nerve is rare and seen most often at its tympanic segment and associated with middle and inner ear anomalies.6 Next, the nerve passes posterior to the cochleariform process, tensor tympani, and oval window. Distal to the pyramidal eminence, the facial nerve makes a second turn, the so-called second genu, which passes downward. Here the mastoid segment of the facial nerve begins. The tympanic segment of the facial nerve has no branches.

Table 8.2 Major branches of the facial nerve

Branch | Location | Function |

Greater petrosal nerve | Geniculate ganglion segment | Parasympathetic fibers for lacrimal gland and salivary glands and visceroafferent fibers for sensation of palate |

Nerve branch to the stapedius muscle | Mastoid segment | Branchiomotor fibers innervating stapedius muscle |

Chorda tympani | Mastoid segment | Visceroafferent taste fibers from the anterior third of the tongue |

Posterior auricular nerve | Mastoid segment or extratemporal portion | Branchiomotor fibers innervating ear muscle, may contain also sensory fibers |

Nerve branch to stylohyoid muscle | Mastoid segment or extratemporal portion | Branchiomotor fibers innervating stylohyoid muscle |

Nerve branch to posterior belly of digastric muscle | Mastoid segment or extratemporal portion | Branchiomotor fibers innervating posterior belly of digastric muscle |

Parotid plexus | Extratemporal portion | Branchiomotor fibers innervating muscles of facial expression (details in Chapter 9) |

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree