Chapter 32 Extensor Tendon Injuries—Primary Management

Outline

The zones of injury have been assigned beginning distally with odd numbered zones located over the respective distal interphalangeal (DIP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), metacarpophalangeal (MCP), and wrist joints, while the even numbered zones are located over the underlying intervening osseous structures (see Chapter 1, Figure 1-7). The detailed anatomy of these tendons is discussed in Chapter 1.

A few general anatomical points are critical to be aware of when evaluating patients with potential injuries to the extensor mechanism. (1) Variations in extensor anatomy are common, such as extensor digiti minimi (EDM) duplication, absence of extensor digitorum communis (EDC) to the small finger. (2) The juncturae tendinum (see Chapter 1, Figure 1-7) connect the EDC tendons of the ulnar four digits and are more common and more substantial (tendon like) on the ulnar part of the hand. An injury to the extensor mechanism proximal to a juncturae can be masked on examination by the ability to extend the injured digit at the MCP joint through an intact juncturae to an adjacent tendon. (3) Because of the superficial location of the extensors partial and complete injuries can and do occur with seemingly minor lacerations. (4) Injuries may be initially compensated for by the duplications and interconnections of the extensor mechanism but a clinically significant deformity can develop with time. (5) A high percentage of these injuries have associated bone, skin, or joint injury.1

Zone 1—DIP Joint

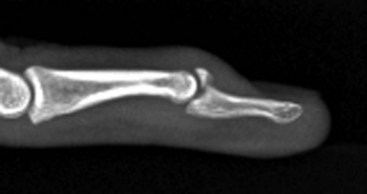

The relatively complex anatomy of the extensor hood becomes much simpler distally as the terminal tendon is the only structure that extends the distal joint. In addition, the terminal tendon is a surprisingly delicate structure when handled surgically, particularly after trauma. Disruption of the terminal tendon at this level is commonly referred to as a “mallet” finger because of the characteristic flexion deformity (Figure 32-1). Closed injuries are the most routinely seen variant and occur from multiple mechanisms ranging from injury in sports with a ball striking the tip of the digit to “trivial” injuries such as tucking in bed sheets. The ulnar digits are more commonly affected and males with this injury tend to have it a younger age than women. Injury is thought to occur from any activity that results in forced flexion of the tip of a digit. Variations include closed, open with or without tissue loss, and mallet fractures (Figure 32-2); it is not infrequent for these injuries to present late after trauma. Mallet fractures involving large portions of the articular surface can lead to joint subluxation.2 Injuries older than 4 weeks have been classified as “chronic.”3

The resulting deformity ranges from a small extensor lag to a lag equivalent to full passive DIP flexion. In some patients the deformity seems to progress over a few hours or days, suggesting that partial injuries may become worse with further trauma or with routine use. Mallet finger injuries may lead to a swan-neck deformity (flexion of the DIP and PIP hyperextension) through overpull of the extensors at the PIP joint. This is more common in individuals with PIP joint volar plate laxity and illustrates the concept that a tendon imbalance at one interphalangeal (IP) joint may lead to an opposite deformity in the adjacent IP joint.4

Closed mallet injuries without a fracture are managed by observation, immobilization, or surgery. Nonsurgical treatment is most commonly used in the treatment of closed mallet injuries and is used for the vast majority, including those with fractures that involve one third of the articular surface or less. Joint subluxation is typically not seen until approximately 50% of the articular surface is involved. Controversy exists over the type of immobilization, length of immobilization, and the need to include the PIP joint. The principle of immobilization is to maintain the DIP joint in extension to approximate the injured structures and allow for healing. Constant immobilization is maintained for 6 to 8 weeks but care must be exercised as dorsal skin compromise occurs, particularly if the DIP joint is positioned in hyperextension. A recent randomized trial suggests that digit-based cast treatment leads to a lower rate of skin problems and improved patient compliance.5 Some authors advocate restarting the period of immobilization if the DIP becomes flexed at any point during the treatment cycle. The same protocol is typically recommended for patients who present subacutely up to at least 8 weeks from injury.

Some residual deformity (extensor lag) in the intermediate and long term is common but rarely functionally limiting.6,7 Furthermore, the apparent extensor lag may improve over an extended period of time of up to 1 year.8

Mallet fractures are also typically managed with a similar protocol of closed treatment. The most accepted indication for surgery is joint subluxation; however, some advocate surgical treatment for large fragments in the absence of subluxation. Techniques include open reduction and internal fixation with small screws, K-wires, or a pull-out suture/wire. Pinning of the DIP joint in extension is commonly considered, particularly in the situation where the fixation is not rigid. A closed technique of extension block pinning, where the DIP joint is brought into full flexion and a K-wire is introduced into the middle phalanx and then the joint is extended. The previously inserted K-wire serves to block extension of the fractured fragment while allowing extension of the remainder of the distal phalanx, reducing the fracture. The two distal phalangeal fragments are then pinned to each other and/or the DIP joint is pinned in a neutral position. The K-wires are left in about 6 weeks, until clinical union.9

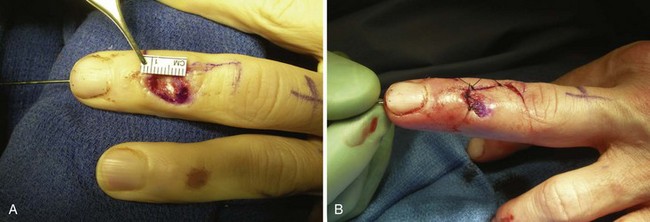

Open mallet injuries are commonly associated with loss of skin and/or tendon substance as well as a traumatic arthrotomy requiring débridement. Even if there is no loss of tissue, the soft tissue injury can be expected to be more severe than with a closed injury. While many open extensor injuries are treated with suture repair of the tendon, the nature of the tendon at this level makes a biomechanically strong repair challenging. Many surgeons choose to add K-wire fixation as an internal splint or to incorporate the skin in a tenodermodesis repair. With a tenodermodesis repair a suture or sutures are placed through the dorsal skin and tendon and the repair includes both skin and tendon with the same suture. The tenodermodesis stitch is left in for 6 weeks in contrast to standard skin sutures so a less reactive nonabsorbable material such as polypropylene suture is used.10

In open injuries with tendon or skin loss, wound management needs to be considered. Local advancement flaps can make up for small defects and skin grafts can also be helpful in select situations (Figure 32-3). There are also indications for heterodigital flaps for loss of larger amounts of skin. Free tendon grafts are also occasionally needed to reconstruct the extensor mechanism. While these more severe injuries are likely to include more loss of motion at the DIP joint due to their more severe trauma, it is important to maintain PIP joint mobility so the overall impact on the total digital motion is minimized.