2 Examination of the upper extremity

Synopsis

Physical examination of the upper extremity starts with a detailed and accurate patient history.

Physical examination of the upper extremity starts with a detailed and accurate patient history.

Physical examination of the upper extremity consists of inspection, palpation, measurement of length, girth and ranges of motion, assessment of stability, and detailed assessment of the associated nerve and vascular systems.

Physical examination of the upper extremity consists of inspection, palpation, measurement of length, girth and ranges of motion, assessment of stability, and detailed assessment of the associated nerve and vascular systems.

Thorough understanding of the anatomy, physiology and biomechanics of the upper extremity is essential to perform a physical examination correctly and to make a correct diagnosis of pathologic conditions of the upper extremity.

Thorough understanding of the anatomy, physiology and biomechanics of the upper extremity is essential to perform a physical examination correctly and to make a correct diagnosis of pathologic conditions of the upper extremity.

Examiners must master correct physical examination techniques based on the anatomic, physiologic and biomechanical rationale.

Examiners must master correct physical examination techniques based on the anatomic, physiologic and biomechanical rationale.

Even if a patient’s complaint focuses on only the hand, the entire upper extremity should be examined.

Even if a patient’s complaint focuses on only the hand, the entire upper extremity should be examined.

It is essential to master correct techniques of physical examination to identify the pathologic conditions of patients.

It is essential to master correct techniques of physical examination to identify the pathologic conditions of patients.

Each technique of physical examination is based on the anatomic, physiologic and biomechanical rationale of the musculoskeletal, nerve or vascular systems.

Each technique of physical examination is based on the anatomic, physiologic and biomechanical rationale of the musculoskeletal, nerve or vascular systems.

Examiners should have their own routine protocol of examination of the upper extremity so not to leave a part unexamined.

Examiners should have their own routine protocol of examination of the upper extremity so not to leave a part unexamined.

Comparison of the affected upper extremity with the contralateral unaffected one helps examiners identify pathologic conditions of the affected one.

Comparison of the affected upper extremity with the contralateral unaffected one helps examiners identify pathologic conditions of the affected one.

Imaging tools such as X-rays, CT or MRI should be used to confirm the diagnosis drawn from the physical examinations or to choose the most possible diagnosis among the several differential diagnoses.

Imaging tools such as X-rays, CT or MRI should be used to confirm the diagnosis drawn from the physical examinations or to choose the most possible diagnosis among the several differential diagnoses.

Obtaining a patient history

Current complaint

In trauma cases, the following data are especially significant:

1. The time of the injury and the interval between the injury and the patient’s presentation should be determined. The interval between an injury and revascularization of amputated fingers has a great effect on the outcome of replantation surgery.

2. The environment in which the injury occurred is important. Whether an injury occurred in a dirty or a clean environment may determine whether infection is likely to be present.

3. The mechanism of injury is also important. For example, information on the posture of the fingers and hand at the time of a tendon laceration is helpful for locating a transected tendon stump.

4. Any previous treatment associated with the injury is documented.

In nontrauma cases, the following data are especially significant:

1. The time at which symptoms such as pain, abnormal sensation, swelling or stiffness began and the subsequent progression of the symptoms is critical.

2. The effects of the symptoms on the patient’s daily life, hobby or job are unique to that patient.

3. One must also ascertain whether or not the symptoms are limited to one part of the body.

4. Activities or postures that aggravate or ameliorate the symptoms are also discussed.

5. The association between time and the intensity of symptoms must be carefully documented (e.g., whether pain increases just after waking up in the morning or during the night).

Physical examination of the hand

Stability assessment

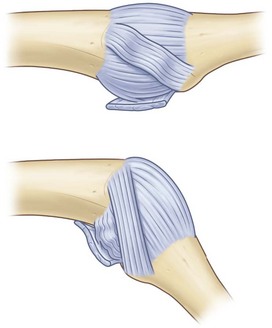

The tightness of the ligaments around a joint, morphology of the surface of a joint and musculotendinous balance around a joint are useful indices of joint stability. When assessing joint stability, the biomechanical and physiological properties of the ligaments should be taken into consideration and the stress forces applied should be appropriate for the ligament in question. For example, the straight portions of the bilateral collateral ligaments of the finger metacarpal (MP) joints tighten when the joint is in the flexed position (Fig. 2.1), whereas those of the PIP joints tighten when the joints are in an extended position. The stability of ligaments is tested by holding the portions distal and proximal to the joint and gently moving the joint passively to stress the ligaments that stabilize the joint. It is useful to measure the opening angle of the affected joint under stress using X-rays and to compare the opening angle of the affected joint with that of the corresponding healthy joint of the opposite hand (Fig. 2.2). The tear of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb MP joint is known to be Stener lesion. The radial collateral ligament instability of the thumb MP joint demonstrates palmar dislocation and ulnar deviation of the thumb MP joint. The radial collateral ligament courses from the distal-palmar to proximal-dorsal direction, the line of which is almost perpendicular to the sagittal axial line of the thumb, the MP joint has tendency to be dislocated palmarly, when the ligament is not functioning. Because the force vector of the adductor pollicis muscle is more transverse to the axial line than that of the thumb abductor muscles, which is more parallel to the axis of the thumb, the thumb MP joint with the radial collateral ligament insufficiency demonstrates ulnar deviation. On the other hand, the long-lasting ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency of the thumb MP joint may also show palmar dislocation.

Musculotendinous assessment

Motion

The presence of abnormal muscles or an abnormal linkage of tendons should sometimes be considered. The flexion function of the PIP joint of a finger is generally accepted to be independent of that of the other fingers because the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendon of each finger has its own muscle belly. The motion of the FDS tendon of the small finger is often linked to that of the ring and/or the long finger and the PIP joint flexion of the small finger often coordinates with that of the ring and/or long fingers.1 The extensor digitorum manus brevis is sometimes present in the middle finger and causes dorsal wrist pain.2

Power

Muscle power is classed according to the Medical Research Council scale, which ranges from zero to five (0–5) (Table 2.1).3 Grip strength is a good indicator of the global muscle strength of the upper extremity. Grip strength is measured using a dynamometer with the shoulder and elbow joints stabilized. The patient grips the dynamometer with the elbow straightened beside the trunk in the standing position or flexed 90° in the sitting position.

Table 2.1 Medical research council scale

| Grade | Physical examination findings |

|---|---|

| 0 | No contraction |

| 1 | Flicker or trace contraction |

| 2 | Active movement with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Active movement against gravity |

| 4 | Active movement against gravity and resistance |

| 5 | Normal power |

Reproduced with permission from: Seddon HJ. Peripheral Nerve Injuries. Medical Research Council Special Report Series, 282. London: HMSO; 1954.3

Tests for specific muscles

Extrinsic muscles

Nerve assessment

Comprehensive sensibility evaluation includes static and dynamic two-point discrimination (2 PD) testing, Semmes–Weinstein monofilament testing, vibrotactile threshold testing, and cold-heat testing. The 2 PD test evaluates the tactile sensation of the skin and assesses density of the perception receptors in the skin. Stimuli generated by the static 2 PD test are mainly sensed by Merkel cells (slow-adapting mechanoreceptors), while the main receptors of stimuli generated by the moving 2 PD test are Meissner corpuscles (quick-adapting receptors). In the static 2PD test, a caliper is applied longitudinally to the digit and the smallest distance between the tips of the caliper that the patient can distinguish is measured.4 The moving 2PD test is the smallest perceived distance between the tips of a caliper that is moved longitudinally along the ulnar or radial aspect of the finger.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree