Erythema Multiforme, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Julia M. Kasprzak

David C. Reid

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

I. BACKGROUND

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute, immunemediated disorder. Ninety percent of EM cases are attributable to infection, the most common being herpes simplex virus (HSV). Clinical findings in HSV-associated EM are thought to be secondary to an immune-mediated response against viral antigen-positive cells containing HSV DNA polymerase pol. Additional etiologic factors implicated in the development of EM, including medications and other infections, are listed in Table 14-1. Medications are believed to incite less than 10% of EM cases.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

EM presents with isolated cutaneous lesions, isolated mucosal lesions, or a combination of the two. Previously, EM was considered to represent a spectrum of disease, including EM minor and major, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Now, however, EM major and SJS are considered distinct clinical entities with similar mucosal erosions, but differing cutaneous lesions.

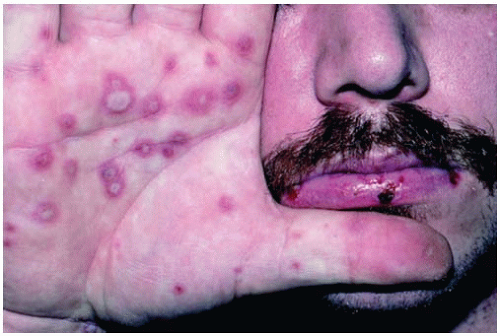

Prodromal symptoms, including fever, malaise, and myalgias, may be present, most commonly when there is mucosal involvement. The classic lesions of EM are targetoid in appearance and comprise the following features: a central area of dusky epidermal necrosis, a concentric dark red inflammatory ring surrounded by a lighter, edematous ring with an outer zone of erythema. The lesions may change in morphology over the course of the episode, and geographic, polycyclic, and annular configurations have been described. In addition, some lesions may appear “atypical” in that they consist of ill-defined, two-zoned targets. Figure 14-1 depicts typical targetoid lesions.

Mucosal lesions occur in 25% to 60% of EM episodes (Fig. 14-2). The oral mucosa is most commonly involved. Lesions present with erythema and

edema and progress to superficial erosions. Symptoms of burning, swelling, and pain can lead to poor oral intake. Importantly, involvement of the ocular and upper respiratory mucosa may occur. Sequelae from mucosal involvement include keratitis, conjunctival scarring, uveitis, permanent visual impairment, esophagitis with strictures, and upper airway erosions leading to pneumonia.

edema and progress to superficial erosions. Symptoms of burning, swelling, and pain can lead to poor oral intake. Importantly, involvement of the ocular and upper respiratory mucosa may occur. Sequelae from mucosal involvement include keratitis, conjunctival scarring, uveitis, permanent visual impairment, esophagitis with strictures, and upper airway erosions leading to pneumonia.

TABLE 14-1 Most Common Causes of Isolated Erythema Multiforme | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Figure 14-2. Mucosal erosions on the lip. (From Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Baskin MN. Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.) |

Classic EM is an isolated, self-limiting disease. The time from disease onset to resolution is usually less than 4 weeks, but can take up to 6 weeks if mucous

membranes are involved. A subset of EM cases are recurrent (≥six episodes per year) and are mostly triggered by recurrent HSV infection. Other cases of EM can be persistent, in that lesions are continuous and uninterrupted.

membranes are involved. A subset of EM cases are recurrent (≥six episodes per year) and are mostly triggered by recurrent HSV infection. Other cases of EM can be persistent, in that lesions are continuous and uninterrupted.

III. WORKUP

No laboratory markers or histopathologic evaluation are required for the diagnosis of EM. Clinical history is paramount in rendering the diagnosis. It is important to inquire about signs and symptoms of infection (HSV or Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and to review the use of new medications. The timing of symptoms is also relevant in determining if the patient has an isolated, episodic, or persistent case of EM.

While it is not necessary for diagnostic confirmation, a skin biopsy may be helpful to exclude other conditions. If HSV lesions are suspected on physical examination, viral culture, HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and/or direct fluorescent antibody should be obtained. When respiratory symptoms are present, M. pneumoniae serologic testing, chest radiograph, and/or throat swab PCR for M. pneumoniae can be obtained. Recurrent idiopathic EM or persistent EM may be further investigated with serologic HSV testing, molecular in situ hybridization/PCR of tissue for HSV, and selected laboratory tests to rule out underlying infectious, inflammatory, autoimmune, or malignant disorders.

Although exceedingly rare, there have been reports linking EM with underlying leukemias and lymphomas. In patients with persistent, recalcitrant EM, solid organ cancers have been described, including gastric adenocarcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

IV. TREATMENT (Table 14-2)

A. Acute Cutaneous Erythema Multiforme

Possible inciting medications should be discontinued.

Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can be used for symptomatic relief of itching and burning of cutaneous lesions.

For suspected HSV-induced EM, antiviral therapy may be considered, but is controversial. Typically, HSV infection precedes EM cutaneous lesions by approximately 8 days. Studies have shown that administration of antiviral medications for the treatment of active postherpetic EM does not alter the clinical course.

B. Mucosal Erythema Multiforme

In minor cases, high potency topical corticosteroid gels, oral antiseptic wash, and oral anesthetic solutions are usually sufficient.

When there is severe, painful mucosal involvement interfering with oral intake, oral corticosteroids may be used to decrease severity and duration of the symptoms. No controlled studies, however, support the usage of oral corticosteroids in the treatment of mucosal EM.

C. Recurrent Erythema Multiforme

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree