Chapter 11 Enzymatic debridement of burn wounds

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

![]() IN THIS CHAPTER

IN THIS CHAPTER ![]() PowerPoint Presentation Online

PowerPoint Presentation Online

Introduction

Immediate or very early wound eschar removal is life-saving in massive, mostly full-thickness burns of more than 50% of the total body surface area (>50% TBSA), and is beneficial in all burns. For less severe burns, especially those with uncertain depth (‘indeterminate’ – the substantial majority of injuries), eschar removal is attempted usually after 2–4 days post injury, though it may be postponed for up to 2 weeks until diagnosis of burn depth becomes clearer.1 At this point in time secondary eschar-related damage has already begun in the zones of stasis and hyperemia. Recent reports indicate that immediate debridement (within 24 hours post injury) may prevent or attenuate the inflammatory response and eschar-related problems. Current ‘early’ eschar removal in the 3–4 days after injury can only be surgical, as no other method or means is fast enough. The choice of surgery, considering its dangers and drawbacks, should be weighed carefully, especially in ‘indeterminate’ burns.2–6

The indication and decision for surgical eschar removal depends on pre-debridement diagnosis. The procedure is traumatic, non-selective, and demanding of resources, general anesthesia, and facilities, but is quick and effective. It sacrifices some of the non-injured surrounding tissues (up to 50%).7 Following surgical debridement, usually not enough dermal and epidermal elements are salvageable for potentially spontaneous epithelialization, so the exposed raw bed should be protected and covered by an autograft (additional sacrifice of donor site) or other permanent cover. Surgical debridement may involve complications such as severe blood and temperature loss, inflammation and infection due to bacterial dissemination, pain, and all the anesthesia-related complications.8–18 More selective debridement has been recently advocated by some to preserve more dermis for grafting or spontaneous epithelialization, with the development of more selective means of surgical debriding (i.e. dermabrasion or Versajet).19,20

Non-surgical ‘conservative’ treatment is based mainly on autolytic (maceration) processes, involving the combined activity of topical medicaments (antimicrobial or chemical agents), contamination and lysis by microorganisms, and the inflammation process combined with daily bathing (showers) with superficial scraping and removal of loose debris and dressing changes. These infectious–inflammatory processes are slow (lasting between 10 and 14 days), and may involve significant systemic and local complications. Using topical antibacterial or anti-inflammatory medicaments may reduce the infectious–inflammatory processes, but will delay eschar separation (sloughing). Locally, all these processes may lead to additional tissue damage, particularly death of the zones of stasis and hyperemia, deepening and transforming partial-thickness damage into full-thickness burns. In addition to its local and systemic significance, the long debridement time with sustained inflammatory–infectious processes can lead to the formation of granulation tissue that will develop into heavy scars.21–25 The benefits of the technique include its relative selectivity and the fact that it is not based on diagnosis, does not involve surgery, and is simple to practice. When the epithelial remnants in the cutaneous dermis are preserved and provided with the proper conditions for proliferation and propagation, the newly debrided dermal bed provides adequate conditions for spontaneous and rapid re-epithelialization, generally in less than 3 weeks. Rapid epithelialization prevents the formation of granulation tissue that may eventually to develop into heavy scar tissue. Non-surgical debridement may involve complications such as fever and infection owing to bacterial dissemination and slow decomposition of the contaminated eschar, enabled by numerous painful dressing changes.24–26

Hand burns, which are involved in 30–60% of all burn patients, have a special place in the field of burn care and demand special attention and treatment. The initial assessment should include not only the depth and extent of the cutaneous injury, but also diagnosis of increased interstitial/compartment pressure (burn induced compartment syndrome – BICS), which may harm local blood perfusion. Circumferential burns to extremities may cause BICS and represent an emergency necessitating pressure release by deep surgical incisions, i.e. escharotomy. Owing to the anatomy of the hand (important and delicate structures crowded in a small limited space without subdermal soft tissue), surgical debridement and/or escharotomy is technically intricate, and because of the difficult diagnosis is often executed late or unnecessarily.8–10,21,22,27,28

Debridement factors and assessment

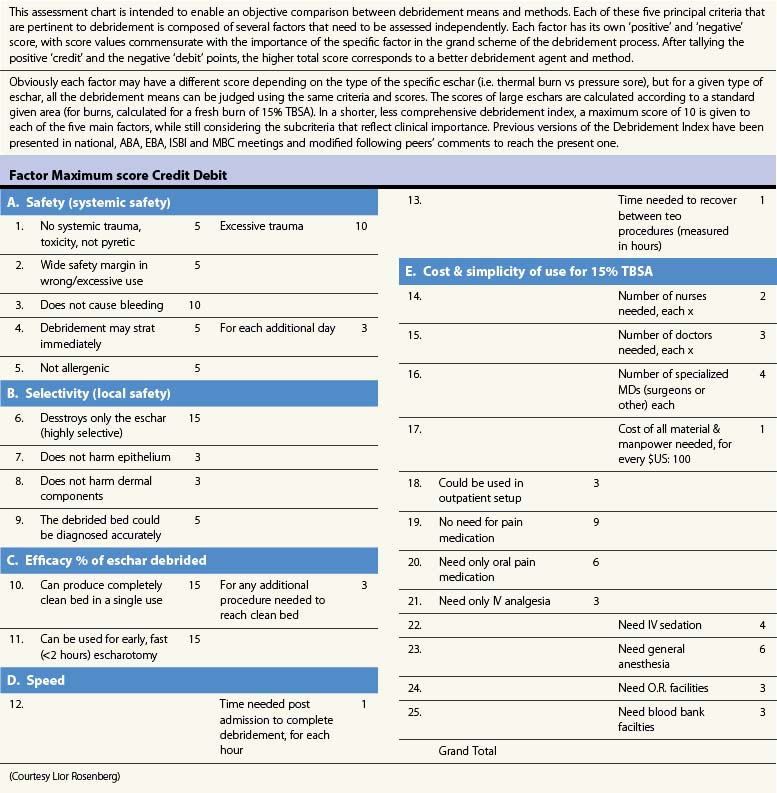

The factors that define the clinical value of any debriding means or methods are as follows:

1 Safety: no systemic side effects, trauma, or bleeding

2 Selectivity: no damage to surrounding local viable tissues (not diagnosis dependent)

3 Efficacy: complete debridement in a single use, with release of BICS

4 Speed: debridement completed as fast and as soon as possible, within hours of admission

5 Cost-efficiency and simplicity of use: minimal specialized facilities and personnel required.

All these factors are as important, and probably even more so, in children, the elderly, and patients with burns of the hands, feet, face, and neck, where important vital structures lie cramped under thinner skin. Assessing the merit of any debriding means or technique should include all of these factors (Table 11.1).