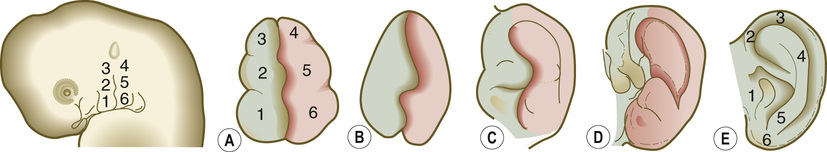

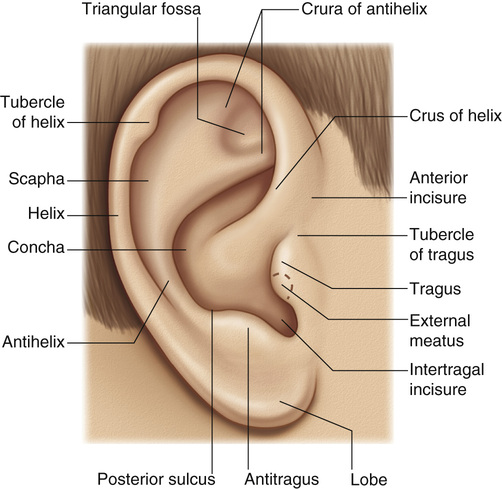

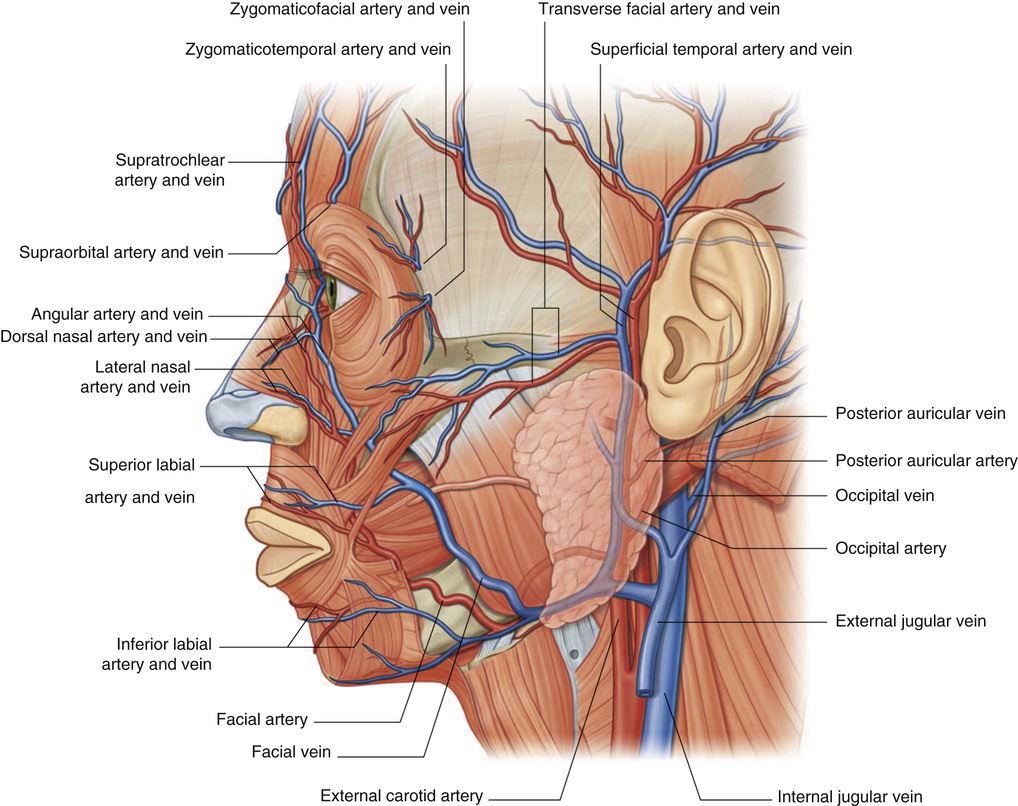

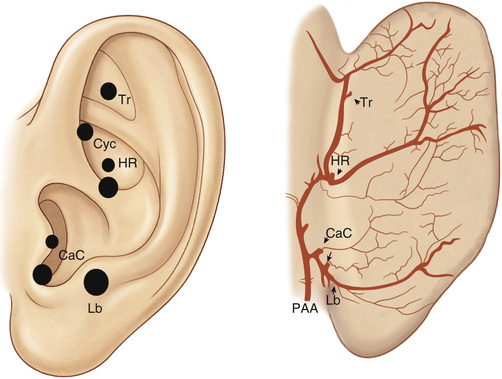

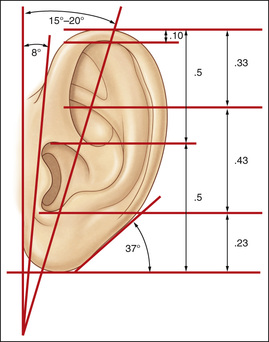

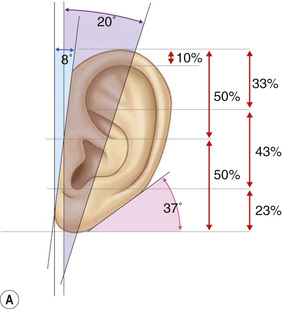

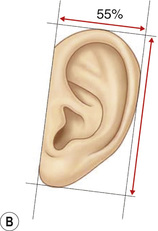

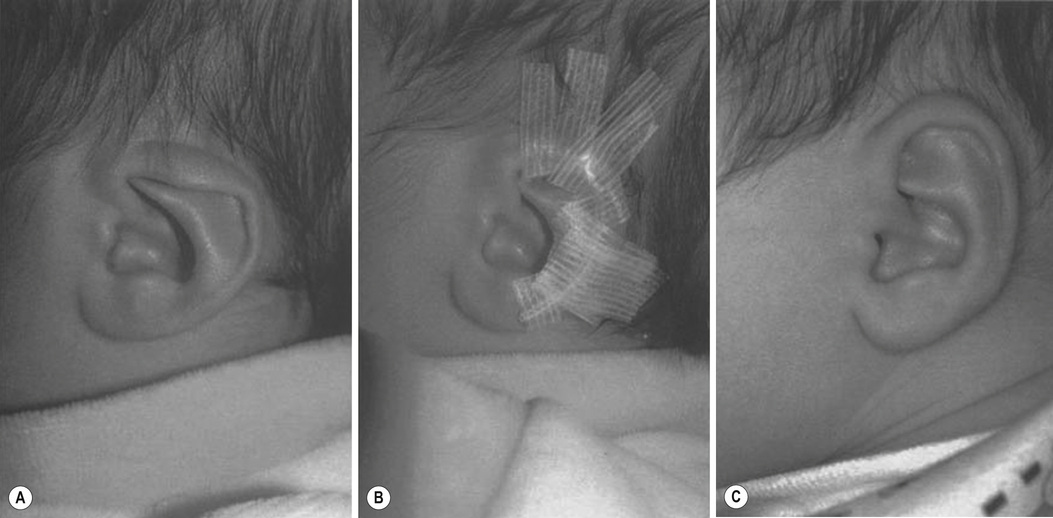

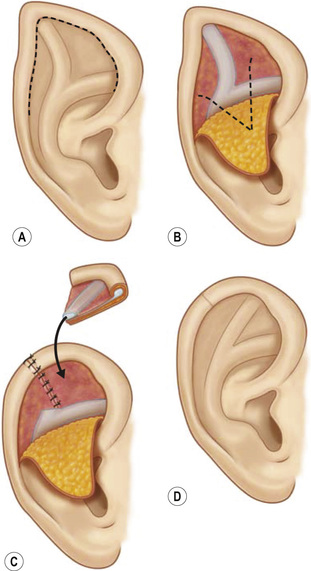

1. Embryology (see Figure 7.1) • The ear arises from the 1st (mandibular) and 2nd (hyoid) branchial arches, which are further defined by the development of six hillocks, appearing during 6th week. • The external acoustic meatus develops from the first branchial groove. • The middle ear and eustachian tube are formed from the first pharyngeal pouch. • The lymphatic drainage of the ear follows embryologic development. ▪ 1st arch structures drain to the parotid lymph nodes. ▪ 2nd arch structures drain to cervical lymph nodes. 2. Anatomy • The external ear: A three-tiered cartilaginous framework with skin on its anterior surface ▪ The complete ear includes the scapha, concha, helix, antihelix, tragus, and lobule as shown in Figure 7.2. • Blood supply: Primary supply to ear is via posterior auricular artery; multiple perforators pierce cartilage to supply anterior ear (see Figures 7.3 and 7.4). ▪ The occipital artery supplies minor contribution to posterior ear. • Sensory innervation of the external ear ▪ Great auricular nerve (C2, C3) ascends from Erb’s point, 6.5 cm below the level of the tragus on the midpoint of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and travels just slightly posterior to the external jugular vein (EJV) ○ Supplies sensory to lower half of ear (anterior and posterior) ▪ Auriculotemporal nerve (V3) ascends with superficial temporal vessels. ○ Supplies the tragus and the anterior/superior portions of auricle and external auditory canal ▪ Lesser occipital nerve (C2, C3) emerges higher than the greater auricular nerve (GAN) and travels along the posterior border of SCM ○ Supplies the posterosuperior aspect of auricle ▪ Arnold’s nerve (auricular branch of vagus; cranial nerve 10 [CN X]) travels along the ear canal. ○ Supplies the concha and posterior auditory canal ▪ External ear block: Place a ring of local anesthetic around the ear. 3. The normal ear (see Figures 7.5 and 7.6) • On frontal view, the helical rim should be seen more lateral than the antihelical rim. ▪ Width of ear is 55% of height. • Projection of the helical rim is 1 to 2.5 cm from the mastoid skin, with a normal scapha-conchal angle of 90 degrees and a normal auriculocephalic (AC) angle of 20 to 30 degrees. ▪ Projection >20 mm or 45 degrees corresponds to a prominent ear. • Increased conchoscaphal angle, deepened conchal bowl, and prominent lobule • The superior and middle thirds of the ear are most likely to be affected. ▪ The most likely cause of a prominent superior third: Absence or effacement of the superior crus of the antihelix. ○ The cephaloauricular angle is also increased and typically measures >25 degrees. ▪ Prominence of the middle third of the ear is most likely caused by hypertrophy of the concha cavum. ○ The concha cavum has a depth of >1.5 cm. ○ The middle third of the ear is located >16 to 18 mm from the mastoid region. • At birth, the neonate’s ears are soft and pliable, which makes molding therapy of ear deformities more successful. ▪ Due to maternal estrogen, which increases cartilage content of hyaluronic acid ▪ Molding is most effective in infants <3 months. ▪ Custom-made mold can be fashioned out of soft putty and affixed into the ear with surgical tape or Steri-Strips. ○ Depending on severity, molding can be continued for several weeks to a few months. • The top two causes of prominent ears are (1) inadequate formation of the antihelical fold and (2) conchal hypertrophy. ▪ An antihelical fold can be created by a posterior approach and suturing techniques. 5. Ear deformations/congenital malformations • Lop ear/cup ear/constricted ear (see Figure 7.7) ▪ Acquired in utero and related to softened cartilage of the upper helix from circulating maternal estrogens. This cartilage lacks sufficient stiffness to support the upper helix. ○ Infants: Respond to shaping with a molding splint formed to match the normal helix ○ Recurrent or older child: Cartilage rasping or surgical options work, including detaching the helix from the scapha and resuturing it to the scapha at a proper angle (see Figure 7.8). ▪ In some cases, the helix can be “pulled” out to normal position. ○ Surgical correction involves release of this abnormal connection and frequently requires skin grafting, or posterior auricular flaps, depending on the severity of the deformity (see Figure 7.9). ▪ Primarily includes a “third antihelical crus” ○ One method of treatment is wedge excision of the third crus (see Figure 7.10). ▪ Congenital malformation with abnormal/rudimentary development and/or absence of ear structures 50% associated with other craniofacial (CF) syndromes/disorders involving 1st or 2nd branchial arch ◆ Orbital auricular vertebral syndrome (Goldenhar) ◆ Treacher Collins syndrome (more common) ○ Inner ear not typically involved (not derived from 1st/2nd branchial arch)

Ear Reconstruction

Ear Reconstruction

Chapter 7