Diseases and Abnormalities of Nails

Herbert P. Goodheart

Hendrick Uyttendaele

Common nail Problems

Common nail Problems

Longitudinal ridging (onychorrhexis)

Brittle nails (onychoschizia)

Onycholysis

Green nail syndrome

Traumatic Lesions

Traumatic Lesions

Subungual hematoma

Median nail dystrophy

Inflammatory Disorders

Inflammatory Disorders

Psoriasis

Infections of the Nail and Surrounding Tissues

Infections of the Nail and Surrounding Tissues

Acute paronychia

Chronic paronychia

Onychomycosis

Digital mucous (myxoid) cyst

Nail Problems: Miscellaneous Disorders

Nail Problems: Miscellaneous Disorders

Leukonychia striata

Yellow nail syndrome

Koilonychia

Dermatomyositis

Subungual verruca

Junctional nevus

Terry’s nails

Half-and-half nails

Dystrophy from preformed artificial nails

Overview

Mammals use their nails as weapons, as primitive tools, for grooming purposes, for scratching, and for the removal of infestations. Similarly, humans use their fingernails to help pick up small objects and to scratch itchy areas. Fingernails protect vulnerable fingertips; toenails protect toes from the impact of footwear and external trauma. Nails also are important contributors to the aesthetic appearance of the hands and feet.

For the health care provider, nail abnormalities may be the first signal that a systemic disease is present.

Common Nail Problems

Longitudinal Ridging (Onychorrhexis)

Longitudinal ridging is a very common and normal variant in elderly persons. It consists of parallel ridges that run lengthwise along the nail plates (Fig. 13.1). Such ridges are more commonly observed in fingernails than in toenails. Occasionally, longitudinal ridging is seen in younger persons. The etiology is unknown and the condition is not indicative of any trauma, infection, or nutritional deficiency.

13.1 Longitudinal ridging. Parallel elevated ridges are characteristic of this normal variant. The ridges may have a beaded appearance. |

There is no treatment available to decrease longitudinal ridging, except for filing and buffing the ridges down with a soft file.

Brittle Nails (Onychoschizia)

Brittle and split (onychoschizia) nails are common in adults (Fig. 13.2). In some people, nails become fragile and easily break off at the free edge. This has traditionally been considered a sign of nail plate dehydration; however, a recent study has indicated that the water content of brittle nails is not significantly different from that of normal nails.

Brittle nails are a common complaint in adult and elderly women and can also be observed in people with iron deficiency and thyroid disease. Elderly men are less apt to present with this problem. The increased incidence in women may be a result of their higher cosmetic awareness, their frequent use of nail products, menopausal status, or frequent exposure to harmful extrinsic factors (e.g., detergents or water).

Traditionally, distal nail splitting has been compared to scaly, dry skin elsewhere on the body. Thus, many treatment recommendations are similar to those for dry skin:

Avoid excessive contact with water soaps, and other detergents. Wear gloves when washing dishes.

Gloves should be worn in cold weather.

Apply moisturizing creams or ointments (e.g., lactic acid creams in 5% to 12% concentrations) at bedtime or after bathing or washing.

Keep the nails short; trim them when they are well hydrated and less likely to be frayed and use a soft file to keep the distal nail edge smooth.

Consider taking the B2-complex vitamin supplement biotin (2.5 mg/day). Some observers claim to have had some success in increasing nail integrity and thickness with this regimen.

Onycholysis

This finding represents a separation of the nail plate from its underlying attachment to the pink nail bed (Fig. 13.3). The separated portion is white and opaque, in contrast to the pink translucence of the attached portion. Normal physiologic onycholysis is seen at the distal free margin of healthy nails as they grow. It usually starts distally and progresses proximally, causing an uplifting of the distal nail plate. When separation is more proximal, the onycholysis becomes more obvious and becomes cosmetically objectionable. In some patients, the nail takes on a green or yellow tinge (see the discussion of green nail syndrome later in the next section).

Onycholysis is most frequently seen in women, particularly in those with long fingernails. It may become painful and may interfere with routine function of the nails (e.g., picking up small objects, such as coins and paper clips).

Pathogenesis

Whereas onycholysis may sometimes result from onychomycosis (tinea unguium), fungal nail infection is only one cause of onycholysis. The causes of this disorder can be divided into two main types, external and internal.

External Causes

Irritants such as nail polish, nail wraps, nail hardeners, and artificial nails can cause the problem. Onycholysis may also be seen in persons who frequently come into contact with water, such as bartenders, hairdressers, manicurists, citrus fruit handlers, and domestic workers.

Trauma, especially habitual finger sucking, athletic injuries to the toes, wearing of tight shoes, and the use of fingernails as a tool, can all cause the disorder.

Traumatic onycholysis of the toenails can be caused by a lack of appropriate nail care. It is often difficult for elderly patients to trim toenails frequently. This may be a result of arthritis, decreases in fine motor control, or a decline in flexibility. Such difficulties may result in long nails that interfere with shoes fitting properly.

Fungal infections (e.g., chronic paronychia or onychomycosis) are another cause.

Some drugs can act as phototoxic agents to induce fingernail onycholysis. Photo-onycholysis usually occurs abruptly on multiple nails at the same time (rather than slowly progressing). Such drugs include diuretics, sulfa drugs, tetracycline, doxycycline, and, particularly, demethylchlortetracycline.

Internal Causes

Psoriasis is the most common cause. Patients generally have evidence of psoriasis elsewhere on the body, or there may be other psoriatic nail findings, such as pitting.

Inflammatory skin diseases of the nail matrix (root), such as eczematous dermatitis or lichen planus, can cause onycholysis.

Neoplasms and subungual warts are possible causes, especially if only one nail is involved (See Fig. 13.20).

Other possible internal causes include thyroid disease, pregnancy, and anemia.

The goal of management is to keep the newly growing nail attached by:

Keeping nails dry and cut closely; proper trimming (along the contour) on a regular basis can protect the nails from injury

Using nail polish sparingly

Avoiding unnecessary manipulation of nails

Treating or avoiding the underlying cause of the problem, if known

Green Nail Syndrome

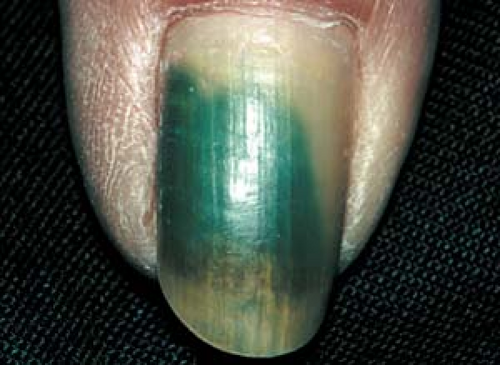

This is a consequence of onycholysis. Green nail syndrome is a painless discoloration under the nail and should not be confused with a subungual fungal infection (Fig. 13.4).

13.4 Green nail syndrome. The “dead space” under the nail often harbors Pseudomonas species. The green color is virtually pathognomonic for Pseudomonas. |

Pathogenesis

The “dead space” under the onycholytic nail serves as an excellent breeding ground for microbes.

Often, Pseudomonas species are present; their presence usually accounts for the green or green-black nail color.

Soak the affected nail twice daily in a mixture either of one part chlorine bleach and four parts water or of equal parts acetic acid (vinegar) and water. This generally eliminates the discoloration.

If possible, avoid or minimize the underlying cause (i.e., the factor that led to onycholysis, as described in the previous section).

Trauma and Inflammation

Basics

Injuries to the nail root (the matrix that directly underlies the proximal nail fold) may be caused by direct trauma, microbes (e.g., fungi, bacteria), inflammatory conditions (e.g., eczema), or a digital myxoid cyst.

These disorders sometimes result in characteristic deformities; for example, nail pitting, “oil spots,” and onycholysis may be seen in patients with psoriasis.

At other times, deformities result from eczema in the proximal nail fold.

Traumatic Lesions

Trauma is the most common cause of nail disorders.

Subungual Hematoma

This condition results from trauma to the nail matrix or nail bed, such as repeated minor injuries (e.g., tight shoes, sports injuries) or substantial impact (as from a hammer).

An acute subungual hematoma that results from rapid accumulation of blood under the nail plate can be very painful (Fig. 13.5), whereas small lesions may be painless and may go unnoticed for some time.

Chronic, painless subungual hematomas that are clearly not the result of trauma may appear similar to a neoplasm, such as an acral lentiginous melanoma (which is very rare). Because the coagulated bloodstains remain until the nail grows out (for 6 to 12 months), the diagnosis may be in doubt for some time.

Junctional nevus is a possibility (see Fig. 13.21; see Fig. 22.51).

Acral lentiginous melanoma should be considered (see Fig. 22.52).

If there is a strong suspicion of melanoma, the nail bed should undergo biopsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree