FIGURE 27-1. Cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the neck in a girl with coexisting lymphomatoid papulosis. Large ulcerated necrotic tumors can be seen on the neck. |

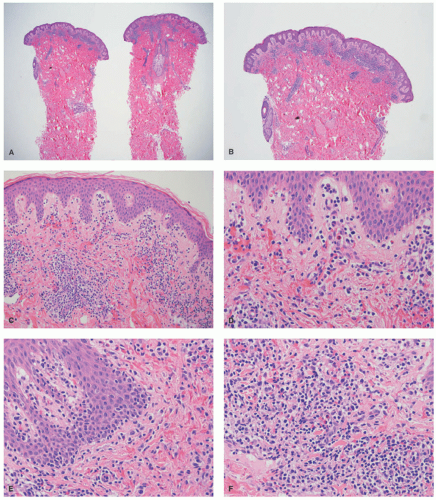

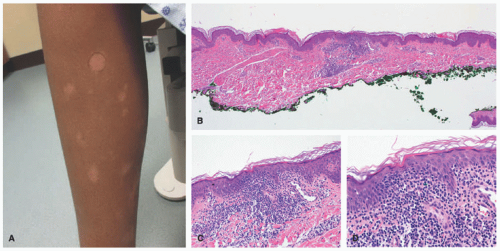

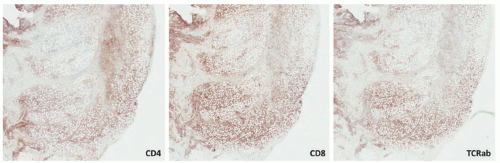

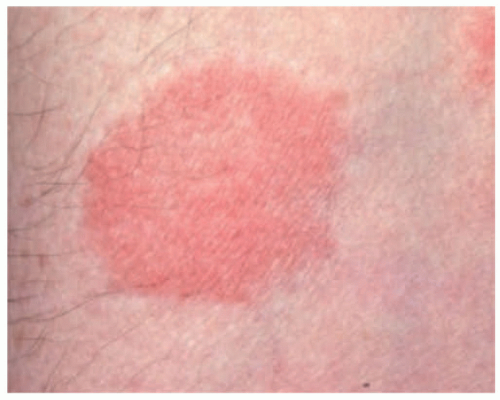

patches (Figure 27-5) and plaques that generally do not progress to the tumoral phase, and has a CD8+ phenotype.30 It has been reported in children as young as 3 years.3,27,31,32,33,34 The male-to-female ratio is nearly equal in the pediatric setting.27,31,34,35 Fink-Puches et al showed that MF represented almost 35% of all cutaneous lymphomas in individuals younger than 20 years.3

and extremities (sun-protected areas). About 6% of patients have solitary lesions. Rare cases of MF can present following organ transplantation.45

FIGURE 27-6. A patch of mycosis fungoides may be similar to other more common childhood dermatoses such as eczema or psoriasis. |

FIGURE 27-7. Distribution of patches of mycosis fungoides is more common in the “bathing suit” area. |

FIGURE 27-8. Patches of mycosis fungoides show poikilodermatous skin change with atrophy, telangiectasia, and dyspigmentation. |

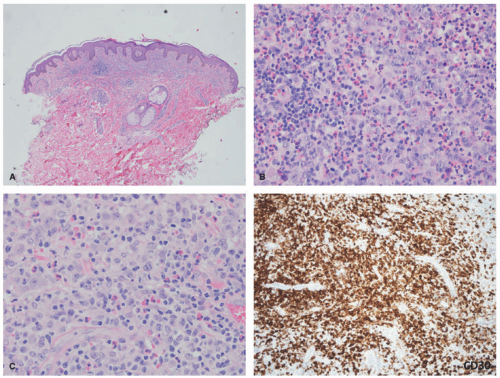

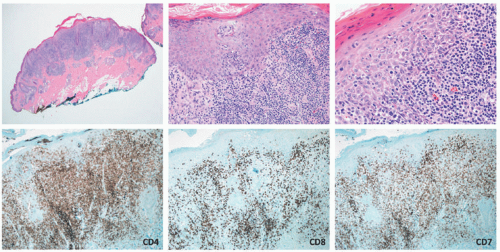

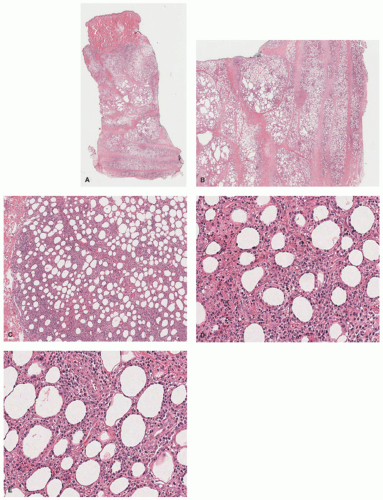

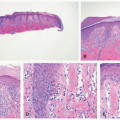

nodular aggregates. Only rarely has such a phenomenon been described in lesions in children.65,66 In FMF, there is infiltration of the hair follicle epithelium with or without epidermotropism (epidermotropism is more frequently seen). The infiltrate involves the infundibulum of the hair follicle and at times deeper portions of the follicle. Follicular mucinosis may be an accompanying feature that can be better demonstrated by colloidal iron or Alcian blue stains. Additionally, FMF is often accompanied by a syringotropic infiltrate.46 However, a Dutch study revealed that interfollicular epidermotropism is actually rare.50 FMF is not usually accompanied by intraepidermal Pautrier microabscesses.67 Dermal eosinophilia can be prominent, particularly during the progression of the disease, and might be a manifestation of an autoimmune response to the keratin of the hair shafts in the dermis. In granulomatous MF (GMF), dense nodular and diffuse granulomas are present in the dermis, with or without epidermotropism, and with destruction of elastic fibers and elastophagocytosis. In the PR variant of MF, prominent pagetoid epidermotropism is noted (Figure 27-14). Such cases show a very impressive clinical response to radiation treatment.

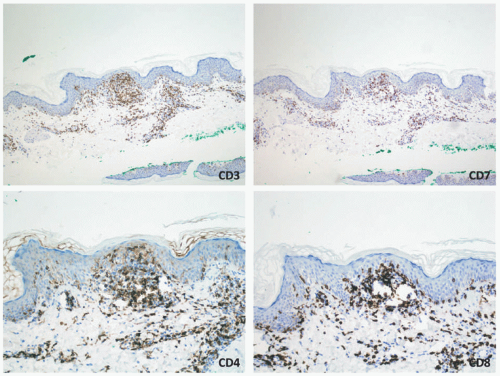

melanocytes at the dermal-epidermal junction, which can be proved with the use of a MART-1 immunostain. Acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma of children (APACHE) can also mimic PR. A dense lymphoid infiltrate beneath the epidermis, and thick wall vessels are seen.80 PL chronica and varioliformis acuta (PLC/PLEVA) can also share histomorphologic features. A lymphocytic vasculitis and interface changes are present in both conditions. As opposed to MF, loss of T-cell antigens (CD7) is not typical. Molecular studies (TCR rearrangement) should not be used to distinguish between both conditions, particularly if the BIOMED primers are being used, because PLC and PLEVA can have positive clonality studies in up to 25% of cases. Next generation sequencing accurately distinguishes between inflammatory dermatoses with clonal populations of cells and cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.81 However, this technique is currently expensive and unlikely to replace TCR gene analysis in the clinical setting. Spongiotic dermatoses (eczema, contact dermatitis, etc) can also enter the differential diagnosis. The latter typically lack significant cytologic atypia of the lymphoid population or aberrant antigenic loss. If the infiltrate is positive for CD30, other CD30+ lymphoproliferative diseases (LPDs) can enter the differential diagnosis (LyP and PC-ALCL). In children, Langerhans cell histiocytosis is also accompanied by extensive pagetoid epidermotropism of the histiocytic cells. As opposed to MF, langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is positive with histiocytic markers (CD68, S100, CD1a, and Langerin), whereas it is negative for T-cell antigens. A word of caution should be made with LCH, as many cases can have clonal rearrangements of the TCR.

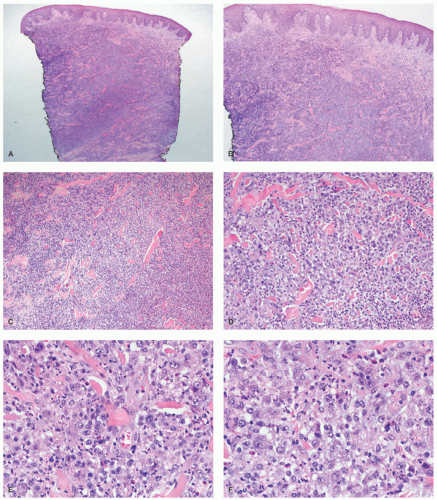

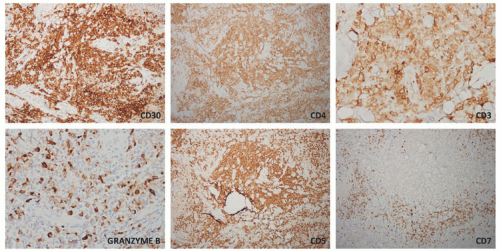

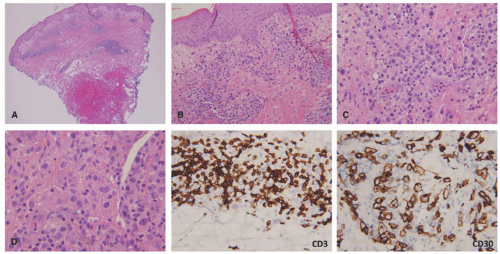

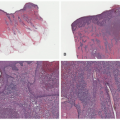

characterized by an epidermotropic infiltrate reminiscent of MF, whereas Type C LyP has features histologically identical to PC-ALCL. Clearly the clinical distinction is more important in a sense than the histologic findings. Cerroni et al showed that a majority of the children represented types A and C, with no examples of type B. In another pediatric series of 250 cases LyP in children, most cases belonged to type A.88 Type D LyP mimics aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma histologically94; this variant expresses other cytotoxic markers such as granzyme and TIA-1. In the latter study, 4 of the 9 patients were less than 25 years of age. Type E LyP is characterized by an angioinvasive and angiodestructive CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell infiltrate with CD30 co-expression; 2 of the 16 original patients were children.95 Another study of 14 children with LyP revealed that 10 cases had a CD8+ cytotoxic phenotype; most cases were considered either type A or type C. Pierard et al introduced the term follicular LyP (type F) to describe a subtype with a predominant perifollicular pattern of infiltration.96,97 A few cases of LyP (type F) have been reported in children.98,99

TABLE 27-1. Lymphomatoid Papulosis, Subtypes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

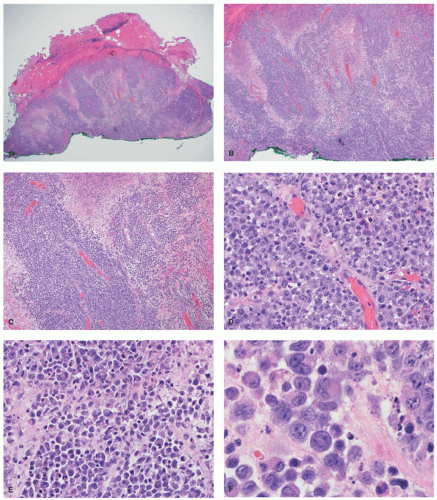

staging procedures. The presence of ALK+ distinguishes this process from PC-ALCL. More recently, molecular studies have proved that systemic ALK-ALCL with the presence of DUSP22 translocations has a clinical outcome similar to cases of ALK+ ALCL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in children can also be ALK+. As opposed to ALK+ ALCL, such tumors are positive only for histiocytic markers and lack the cellular pleomorphism that is typical of ALCL cases.

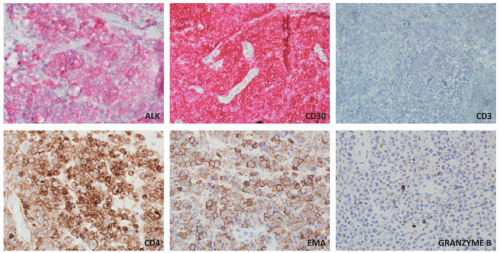

Raynaud disease, and Kikuchi disease.134 Yi et al140 showed a series of 11 cases of SPTCL initially diagnosed as autoimmune disorders; the authors divided the original diagnoses into three separate groups: (1) a group with a preceding diagnosis of erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, lupus profundus; (2) vasculitis; (3) inflammatory myopathy-like lesions. The authors speculated that patients with inflammatory myositis and/or Behcet’s represented paraneoplastic manifestations of SPTCL. Some of these patients (2/11) had elevation of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in the serum, anti-DS DNA antibody, and one patient had an elevated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. A study from the Mayo Clinic on a series of 23 patients revealed preceding diagnoses of autoimmune disorders in approximately 57% of patients, including lupus panniculitis, erythema nodosum, venous stasis, Weber-Christian disease, cellulitis, and granulomatous panniculitis of unknown etiology. The association between SPTCL and lupus erythematosus profundus (LEP) has led to the hypothesis that perhaps the two entities represent two ends of the same spectrum.141,142 Some cases of lobular panniculitis with a CD8+ phenotype can occur in children in association with clonal populations of T cells in the setting of congenital immune deficiency syndromes. Rare cases in association with HIV143 and sarcoidosis have also been documented.144 The association between certain medications and development of SPTCL has been described in patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy (etanercept),145 and following rituximab and cyclophosphamide.146 More unusual presentations have been reported in patients with Down syndrome,147 cervical cancer,148 during pregnancy,149 and neurofibromatosis type 1.150

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree