CHAPTER 45 Correcting the cleft lip nose

Physical evaluation

• Determine the optimal timing for surgery.

• Assess the basal skeleton (maxilla) for retrusion and possible Le Fort I advancement.

• Assess the airway for breathing difficulties.

• Identify deviations in the bony dorsum.

• Assess the middle vault for deviations.

• Identify malpositioning of the tip cartilages.

• Observe asymmetries in the skin envelope, including the alar base.

Anatomy

One of the more dramatic forces acting upon the cleft lip nose is the deformed maxilla, which serves as the foundation to the nose. Latham described the outward splay of the premaxilla, deficiency of the anterior nasal spine, and retropositioning of the footplate of the medial crus as causal factors resulting in secondary deformities of the nasal tip, the lower and upper lateral cartilages and the bony base. Cadaveric studies on lower lateral cartilage deformity secondary to the maxillary deformities have been described by Broadbent and Woolf. The pathogenesis of maxillary malposition on the septal and bony dorsal deviation has been detailed by Hogan and Converse’s “tilted tripod” deformity (Fig. 45.1). They postulated that retraction of the alveolus on the cleft side and projection of the premaxilla induces a “buckling” of the nasal septum and bony dorsum resulting in deviation.

Technical steps

The first consideration in assessing a patient with a cleft lip nasal deformity is determining the optimal time to perform secondary rhinoplasty. The decision is a balance of maximizing the aesthetic outcome of the procedure with the psychosocial impact of the deformity. Ideally, cleft lip nasal reconstruction is performed after the time of complete facial maturity, eliminating the variable of subsequent growth on the outcome of the surgery. However, the psychological impact of a severe nasal deformity may prompt the surgeon to perform an earlier intervention. Children who have undergone cleft lip repair without nasal correction can present with deformities that can significantly impact their social development. Indeed, we have performed secondary rhinoplasty in children as early as 6 or 7 years of age. If early rhinoplasty is done, a conservative anatomic approach is used to preserve facial growth. Ultimately, timing of surgery should be individualized to the patient. Children who appear well-adjusted can certainly undergo surgery after full facial growth has occurred. Those patients who appear socially avoidant, frequently absent from school or social events, and who present with significant nasal deformities should be considered for earlier intervention. If early nasal reconstruction is performed, the parents should be informed that a second rhinoplasty will be necessary if subsequent growth produces further deformities to the dorsum and tip.

Once the timing of the surgery has been determined, occlusion and midface projection is assessed. Midface retrusion commonly develops in the cleft lip patient during facial maturation, leading to a midfacial concavity and malocclusion (Fig. 45.2). Correction of the skeletal base, usually by Le Fort I advancement osteotomy, should be performed prior to rhinoplasty. Anterior advancement of the upper jaw, which serves as the foundation to the nose, will increase tip projection, increase the nasolabial angle, and can restore aesthetic balance to the face. These changes can affect the surgical planning of the secondary rhinoplasty or obviate the need for rhinoplasty entirely (Fig. 45.3). We do not perform cleft nasal reconstruction at the time of orthognathic surgery.

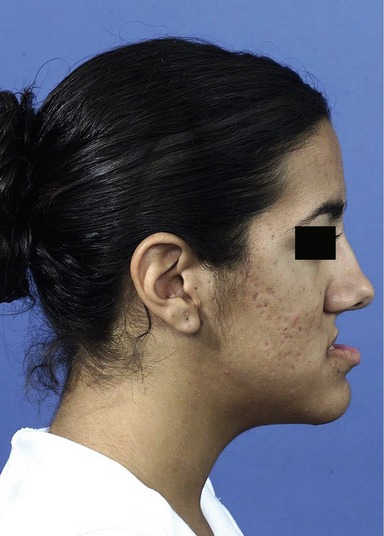

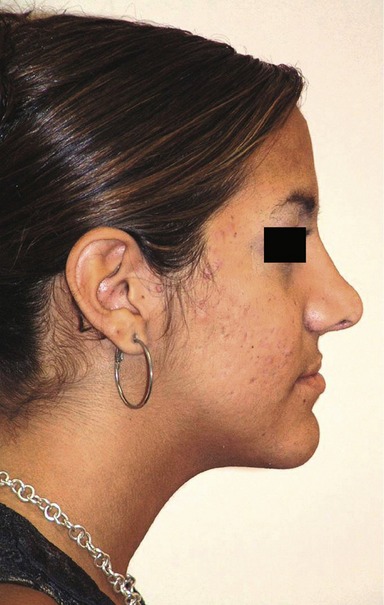

Due to the severe tip deformity typical of cleft lip patients, an open rhinoplasty approach is used in all cases, save those with mild tip deformities. Although much attention in unilateral cleft nasal deformity has focused on tip correction, anatomic realignment of the domes without addressing dorsal deviation will result in a twisted and misshapen nose (Figs 45.4 and 45.5).The unilateral cleft lip nasal deformity will typically have severe nasal dorsal and septal deviation that is extreme compared to what is seen in the common rhinoplasty patient and involves the bony as well as the cartilaginous septum.

Fig. 45.4 A patient with a typical cleft nasal deformity. Although most of out attentions goes to the tip, note the significant deviation of the dorsum.

Fig. 45.5 The same patient in Figure 45.4 after secondary rhinoplasty. The nasal tip has undergone adequate correction however the dorsum remains deviated, compromising the final result.

The authors’ technique of cleft lip rhinoplasty starts with a radial submucous resection. The septum is approached intranasally, from the cleft side. The mucoperichondrium over the anterior aspect of the cartilaginous septum and vomer is incised with a #15 blade and mucoperichondrial flaps are elevated widely to include the septum as well as the floor of the nose. As the cartilaginous septum and nasal floor are derived from separate embryologic origins, the mucoperichondrium is tethered at the junction of these two structures, necessitating sharp dissection. Once the mucoperichondrial flaps are elevated bilaterally, the septum is harvested, with care to preserve at least 8 mm of dorsal and caudal cartilage. A 7 mm osteotome is then used to separate the deviated vomer from the nasal floor. With the aid of a Takahashi rongeur, the deviated vomer is removed, along with the perpendicular plate, posteriorly to the sphenoid and superiorly to the roof of the nose.

After radical submucous resection, the bony dorsum is straightened using a monobloc nasal osteotomy described by Blair and Brown (Fig. 45.6). The septal surgery removes the “spring” in the septum which would otherwise push the nasal bones back in its previously deviated position. The bony dorsum is osteotomized along all three “bony” sides to move the dorsum as a single piece. Therefore bony rasping and infracturing is contraindicated when performing the monobloc osteotomy, as comminution of the bony dorsum may result.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree