23.1 Congenital anomalies of the breast

Synopsis

The term “tuberous breast” is used to indicate a great variety of breast deformities that may present very different anatomical-morphologic characteristics, with differing degrees of severity.

The term “tuberous breast” is used to indicate a great variety of breast deformities that may present very different anatomical-morphologic characteristics, with differing degrees of severity.

Hypoplastic tuberous breasts can be classified into three main types: type I, type II, and type III.

Hypoplastic tuberous breasts can be classified into three main types: type I, type II, and type III.

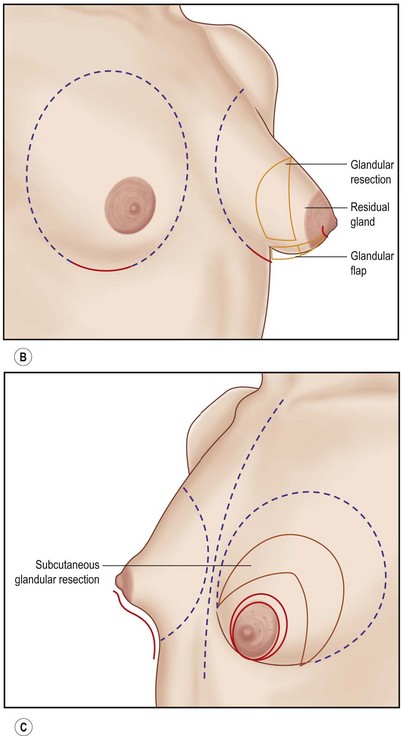

Glandular flap tissue is transferred from the area of surplus to the area of deficiency. There are four main types of flaps used to correct these deformities: Flap type I (variously shaped) is used to correct type I breast deformity. Flap type II is used for type II breast deformity, in order to correct the typical deformity of the mammary profile due to retroareolar glandular protrusion. Flap type III and flap type IV are used in different ways to correct other breast type II deformities, according to the particular characteristics present in each single case.

Glandular flap tissue is transferred from the area of surplus to the area of deficiency. There are four main types of flaps used to correct these deformities: Flap type I (variously shaped) is used to correct type I breast deformity. Flap type II is used for type II breast deformity, in order to correct the typical deformity of the mammary profile due to retroareolar glandular protrusion. Flap type III and flap type IV are used in different ways to correct other breast type II deformities, according to the particular characteristics present in each single case.

Introduction

The term “tuberous breast” was described for the first time by Rees and Aston in 1976,1 and is used to indicate a great variety of breast deformities, which may present very different anatomical-morphologic characteristics with differing degrees of severity. Various names are used to describe the deformity such as: tuberous breast; tubular breast; Snoopy breast; nipple breast; domed breast; herniated areolar complex; narrowed-based breast; constricted breast; lower pole hypoplasia. This creates great confusion, especially when describing the different types of surgical technique utilized for its correction. An author often describes a precise surgical technique for the treatment of such malformations, without making a precise distinction between the different types of anatomical deformity or degree of severity of such malformations.

This chapter considers the different forms of highly hypoplastic tuberous breast and some nontuberous congenital mammary asymmetry, without taking into consideration complex malformations of the chest wall such as pectus excavatum. (However, malformation of the muscular apparatus found in Poland syndrome is discussed Chapter 23.2).

Basic science/disease process

From the embryological development point of view, we can summarize by saying that the mammary bud is differentiated and formed during intrauterine life until birth2 but its full development as the mammary organ occurs at the time of puberty. Such a period may vary from 7–9 to 15–16 years of age depending on different racial and constitutional characteristics.3

From an anatomical point of view, the mammary organ is formed by the split of two superficial layers of the superficial fascia, which continues into the superficial abdominal fascia (“fascia of Scarpa”). The superficial layer and the deeper layer of the superficial fascia lie anterior to the fascia pectoralis. These layers are penetrated by fibrous attachments that originate deeply behind the thoracic muscle, penetrating the parenchyma and the superficial layer of the superficial fascia, anchoring them in front of the derma that covers the breast in a more or less consistent manner.4 These fibrous attachments are called Cooper’s ligaments and represent the so-called suspension system of the breast, which determines the degree of effectiveness of the cutaneous glandular adhesion.

The etiology of the tuberous deformities is neither clear nor well-defined; some authors consider the absence of the superficial layer of the superficial fascia at the level of the areola an important element. Others stress the importance of objective clinical data in which we can observe, in different types of tuberous breast, the presence of a fibrous constricting ring around the areola.5,6 Such a constricting ring can be more or less dense and more or less complete; sometimes, this ring is present only around the inferior half of the areola and extends itself to the inferior pole of the breast, like a fibrotic fascia, preventing or holding back the growth of the mammary gland. According to Mandrekas et al., this fibrotic ring represents a thickening with fibrosis of the superficial fascia or hypertrophy of the Cooper’s ligaments.2 The result, in any case, is that the mammary gland cannot expand in its inferior quadrants.

Almost all publications that discuss the subject of the tuberous breast describe a gland more or less herniated into the areola, with consequent areolar widening. Almost all classifications of the tuberous breast take into consideration this concept and distinguish the various types of deformities according to their location, degree of severity and lack of mammary development in the various quadrants.1–36 However, in my opinion we should accept this definition and classification only for one type of tuberous breast, defined here as type I (Figs 23.1.1, 23.1.2), and which is characterized by severe hypotrophy of Cooper’s ligaments. The definition is not suitable to describe, e.g., the breast deformity in Case III right breast (see below), which is classified here as tuberous breast type II (Fig. 23.1.3). This type of tuberous breast presents a very small and compacted areola with the gland protruding behind it and pushing the areola forward, without widening it. The areola also presents a strong cutaneous glandular adherence due to hypertrophy of Cooper’s ligaments (Fig. 23.1.6A,B). These morphological clinical features are indeed completely different from those we observe in a type I tuberous breast.

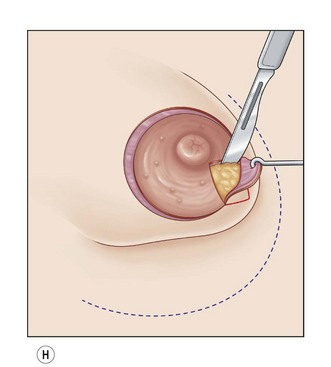

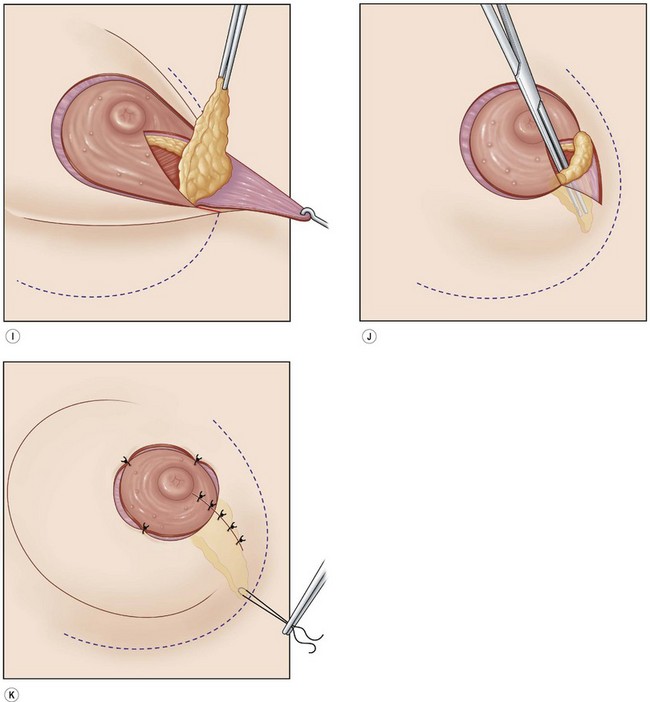

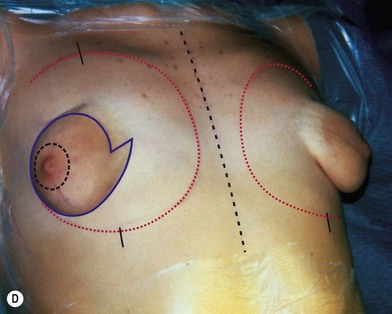

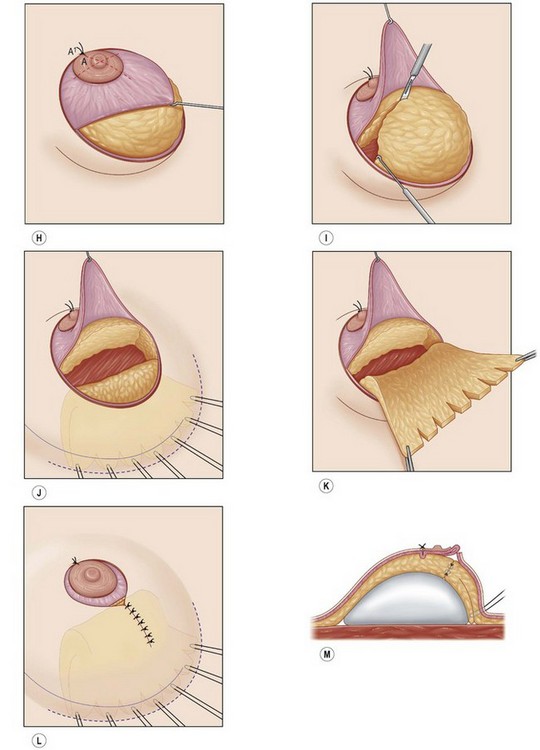

Fig. 23.1.2 (A,B) The small glands herniated into two very expanded areolar sacks with an extremely lax and thin skin, presenting numerous cutaneous peri-areolar striae. The nearly total loss of glandular cutaneous adherence in the mammary quadrants is due to atrophy or absence of Cooper’s ligaments. This characteristic is more evident in Fig. 23.1.2C. (D) Preoperative skin markings. (H) The new reduced areola is lifted in its new position. The dermis of the inferior pole is undermined up to the inferior border of the areola. (I) The dermal flap is lifted. The herniated gland is transversally incised at full thickness from the inferior border of the new areola, down to the muscle-thoracic plane. (J) A square-shaped glandular flap is exposed, multiple small incisions on its free margins are performed in order to spread it in fan like shape, allowing a wider distribution along the new inframammary fold. (K) Few transcutaneous stitches are performed fixing into the desired position the free margins of the flap. (L) The flap is fixed into position, the prosthesis is implanted in the pre-pectoral plane, the skin is sutured with a periareolar and a short vertical scar in the inferior pole. (M) Lateral vision at the end of surgery. The prosthesis is placed in a pre-pectoral plane. The glandular flap is folded under the skin of the inferior pole, with the margins fixed at the new IMF with few transcutaneous stitches. The dermal flap from the inferior pole, in this unusual solution, is folded under the areola between the ducts, through blunt dissection, to increase areolar projection. (N) This 10-year postoperative result still shows the good shape, volume and symmetry achieved. (P) This oblique 10-year postoperative result shows the good anatomical shape of the breast with a smooth superior pole and a full inferior pole, although round prosthesis were utilized.

(A,B,D, reproduced with permission from Muti E. The tuberous breast. SEE Editrice Firenze; 2010.)

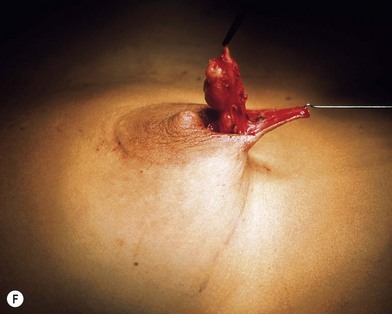

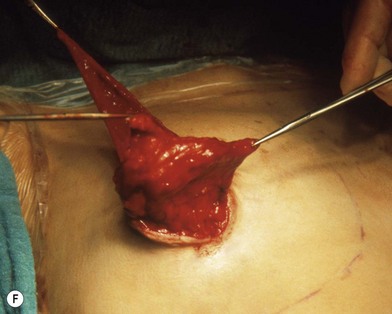

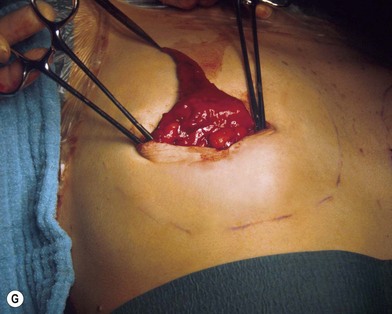

Fig. 23.1.2 (C) The small breasts are positioned rather high on the chest wall and very lateralized on the thorax externally to the hemi-clavicular lines. The glandular base, herniated into the areolar sack, is surrounded by a well defined fibrotic constrictive ring which makes the breast appear like hanging on the chest wall. (E) After the de-epithelialization, the reduced areola is lifted and the gland is shown appearing totally herniated and leaning on the thorax. (F) We can observe the thin dermal flap which was covering the inferior pole being undermined and cranially lifted. The mammary gland, seen in Fig. 23.1.2E, exposed and leaning on the thorax, is transversally incised to the level of the inferior border of the new reduced areola. We then proceed to incise the gland at full thickness up to the muscle thoracic plane and to vertically open it in its deep surface, thus creating a wide square shaped flap with an inferior subcutaneous pedicle based on the superficial blood net. (G) The glandular flap has been deeply and caudally folded over toward the new inframammary fold, creating a sort of thin lower pole. (O) The 18-year postoperative result. The scars are slightly evident due to bad skin quality and initial cutaneous suturing tension. (Q) 18 years postoperatively. The result is unchanged over the years, and actually enhancing the natural look of the breast.

(E–G, reproduced with permission from Muti E. The Tuberous Breast – See Editrice Firenze, 2010.)

In the pathogenesis of these malformations we could assume the existence of a common initial pathogenic element, which differentiating in a precocious manner, produces the formation of different morphological entities which require, in the author’s opinion, a different corrective surgical approach. (See, e.g., the difference between Case II, Figure 23.1.2 and the right breast in Case III, Figure 23.1.3.)

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Examination of the patient

Carefully evaluate details such as:

• The shape of the breast and its essential anatomical features, which allows classification of the breast into the proper typology

• Possible breast asymmetry, even if minimal, and also any asymmetry of the thoracic wall

• Cutaneous quality, degree of skin laxity, presence of any cutaneous striae

Classification of the different types of tuberous breast deformity

For long time I (the author) reflected over the necessity for a classification for the numerous and diverse types of tuberous breast, but could not find agreement with the various current proposed classifications.2 However, I can now identify the most important elements that combine into a broad family of similar groups of the numerous diverse forms of tuberous-tubular deformity. After careful consideration, I have distinguished three different types of hypoplastic tuberous breasts: type I, type II, and type III. This chapter presents some significant clinical examples which I have encountered in my practice.

Type I: tuberous breast

The most significant morphologic characteristics are as follows:

• Mammary tissue herniating into an expanded areola with lax and thin skin presenting poor cutaneous glandular adherence, sometimes occurs only in the half inferior portion of the areola (Fig. 23.1.1A–C), but sometimes in the whole areola, which is generally very expanded (Fig. 23.1.2A–C). The Cooper’s ligaments seem to be hypoplastic or absent.

• The inframammary fold (IMF) is very cranialized with a fibrotic constriction, which appears like a constricting ring surrounding, almost completely, the small gland (Figs 23.1.1B, 23.1.2C)

• Often, the breasts are positioned laterally on the chest wall with a wide intermammary space.

Type II: tuberous breast

The most significant morphologic characteristics are as follows:

• Severely hypoplastic breast with solid skin, small or very small areola, and strong cutaneous glandular adherence

• The mammary base is constricted, although the constricting ring is not so evident

• The inferior pole is absent, flat, or concave

• The inframammary fold is absent

• Typical glandular protrusion behind the areola with deformity of the inferior border of the areola; such deformity is enhanced after the introduction of the prosthesis, even when releasing incisions of the inferior pole are performed.19,26

• The areolas are mostly positioned on the most lateral aspect of thorax quadrants (see the right breast in Fig. 23.1.3A,C).

Type III: tuberous breast

The most significant morphologic characteristics are as follows:

• The breasts are normoplastic

• Breasts appear basically tubular

• A “dive” ptosis and a nipple-areola-complex turning downward

• A circular “mammary footprint” positioned generally high, although not excessively lateralized, on the thorax

Treatment/surgical technique

General considerations

A number of techniques have been described to correct these breast malformations1–36 but because of their great polymorphism, it is impossible to adopt a single ideal surgical technique suitable to each single morphological feature or for every type of tuberous deformity. Therefore, in trying to resolve this difficulty, I came to the conclusion that there could be a solution to this problem by adopting a common basic concept which could be modified, adapted and tailored to each single case.

The concept includes the creation of glandular flaps of different shapes designed in such a way to mobilize the mammary tissue and redistributing it according to the need of each single case. Furthermore, with the creation of these flaps, we are able to obtain the opening of the constricted and fibrotic mammary base. The glandular flap sculpted at full thickness down to the pectoralis fascia allows the opening of the mammary base, interrupting the fibrotic constriction present at the base of the breast. To complete the above described manoeuvres, the author performs gland and subcutaneous deep releasing radial incisions according to Rees and Aston1 and Maxwell.6

In less hypoplastic breasts, the desired result is obtained through the so-called deep glandular unfurling flap manoeuvre, also defined as unfurling of the deep surface of the mammary base.4,9,16 Moreover, according to each specific morphologic characteristic, possible correction is performed, such as lifting and reduction of the areola or areolas, tailored reduction of the mammary gland, in cases of asymmetry and reduction of the cutaneous sack. Once the deformity has been completely corrected, we can implant the mammary prosthesis.

The selection of the type of prosthesis (round or anatomical, etc.), the choice of prosthetic pocket, and access for the implant will vary from case to case and is explained during the description of the surgical technique adopted for each single case. In the author’s opinion, it is very important to avoid the use of heavy and large size prosthesis. It is important to remember the young age of many of patients and that the bigger and heavier the prosthesis, the more frequent and more important will be the inconvenience caused by its size and weight: relaxation and thinning of the skin, lowering of the prosthesis with pseudoptosis, and visibility and wrinkling of the prosthetic borders. Smaller and lighter prostheses result in less or inexistent future potential problems. Furthermore, it is now possible to supplement prosthesis where the size is considered insufficient, or to soften the mammary contour through the use of lipostructure according to the Coleman technique.13 With this technique, we may even be able to substitute the use of prosthesis completely. This is a future ideal goal.

Surgical technique

Glandular correction flaps

The types of glandular flaps are:

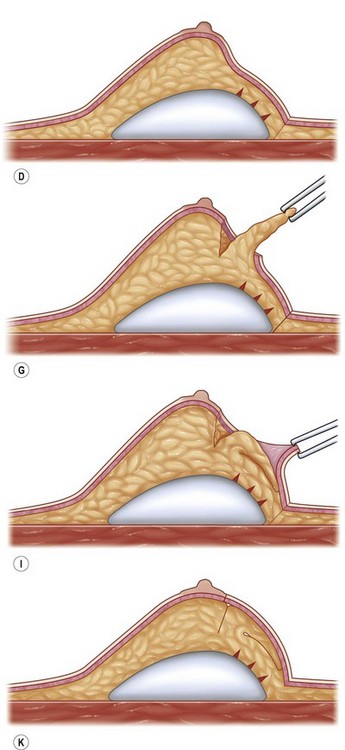

Glandular flap type I

Glandular flap type I is created with a central inferior glandular flap with an inferior superficial pedicle, which will be sculpted at full thickness down to the thoracic plane, presenting its apex toward the base of the nipple and its pedicle based on the subcutaneous vascular blood net, at the level of the inferior constrictive border or pseudo infra mammary fold. The size and shape of the flap will vary from case to case, but it usually includes the gland that appears herniated into the areola. The flap is horizontally incised at the level of the inferior border of the areola down to the muscle-thoracic plane, then it is deeply and caudally folded over, bringing its apex toward the new inframammary fold (Fig. 23.1.1D–M). This surgical procedure will be then completed according to each particular case with other details such as lifting/reduction of the areola, remodeling of the retroareolar glandular tissue, conization of the mammary cone, placement of the prosthesis and closure of the skin incisions.

The aims of this flap are as follows:

Glandular flap type II

Glandular flap type II is correlated with tuberous breast deformity type II (see right breast of Case III, Fig. 23.1.3A,C).

• To eliminate the retroareolar glandular protrusion that determines the deformity of the breast profile

• To undermine the tense skin below the areola on the central part of the inferior pole. This allows the detachment of the Cooper’s ligaments, eliminating the strong adherence between the skin and the gland

• To interpose the small flap between the skin and the gland thus avoiding the recurrence of the defect

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree