Chapter 20 Closed Avulsion or Rupture of Flexor Tendons

A Traumatic Avulsion of Flexor Tendons

Outline

Closed traumatic avulsion of the insertion of flexor tendons is a relatively common injury, particularly in athletes. The majority of injuries involve the profundus tendon at its insertion1–4 and, less frequently, the superficialis5,6 or both tendons.7–10 Avulsion of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendon can be directly from the middle phalanx5 or can be associated with a middle phalangeal cortical bone avulsion.6 Avulsion of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon occurs most commonly at the bony insertion on the distal phalanx, with or without bone fracture.1,2 The injury has been reported to occur in all fingers, but the ring finger is involved in more than 75% of cases.1,2,4 Satisfactory results of surgical repair are usually obtained in most cases if the diagnosis is made quickly. However, impairment of the function of the finger can result from a late diagnosis. In these chronic cases, the results of surgical treatments are often unpredictable.

Background

In 1960, Gunter11 reported avulsion of the FDP tendon occurring in eight rugby players. In 1970, Carroll and March12 reviewed 35 cases and emphasized the particular involvement of the ring finger and the irreversibility of the injury once the tendon had retracted into the palm. The “grasping jersey” mechanism of this trauma was specified by Folmar et al13 and Chang et al.14 A classification into three types according to the amount of tendon retraction has been proposed initially by Leddy and Packer in 19771 and then in France by Mansat and Bonnevialle in 19852 after review of a series of 19 cases. In 1981, Smith15 described a fourth type, with avulsion of the profundus tendon in association with a bone fracture of the distal phalanx. Al-Qattan, in 2001,16 added a type V with tendon and bony avulsion and transverse fracture of the distal phalanx. Only case reports have been published of traumatic rupture of the FDS.5,6,13,17

Mechanism of Injury

Many of these injuries occur in rugby or American football, when the finger is forcibly extended during a maximum contraction of the profundus flexor muscle. The injury occurs when a player is attempting to make a tackle and the little finger slips off the opposite player’s pants or jersey (Figure 20[A]-1). As this occurs, the ring finger is caught in the pants or jersey. Because of the mechanism of injury, the lesion has been termed “jersey finger” or “rugby finger.”2,18–20 Other etiologies have been reported, including blast injury21 and closed blunt trauma.22

The ring finger is most susceptible to avulsion of the FDP tendon.1 Several studies have shown that the insertion of the profundus tendon is anatomically weaker in the ring finger than in the middle finger.19,23 The FDP of the ring finger is tethered in the palm by a bipennate lumbrical muscle,19 and the anatomic arrangement of the extensor tendons in the ring finger may also relate to the susceptibility of the ring finger to rupture.1

When the four long fingers are grasping an object with force, they bear strong traction, which causes acute hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. The index, whose muscular belly is independent, can release its grip before the others. Because the muscular part of the profundus is united to the surrounding structures and because of the existence of tendinous connections, the ring finger is submitted to the constraint along with the middle and little fingers. Because of the shorter size of the little finger, it closes up before the others. This leaves the middle and ring fingers to oppose this strong hyperextension force. The distal insertion of the ring finger, being weaker than that of the middle finger, gives away first.2

Classification

The amount of injury to the extrinsic vascular supply of the distal flexor tendon is proportional to the degree of retraction of the avulsed tendon. The short vinculum, located at the neck of the middle phalanx and at the DIP joint, is injured when the FDP tendon is avulsed from the distal phalanx. However, the tendon may be still supplied by the long vinculum located on the FDS tendon closed to its chiasma, which extends to the FDP tendon. The intactness of this long vinculum determines the severity of the injury.24–26

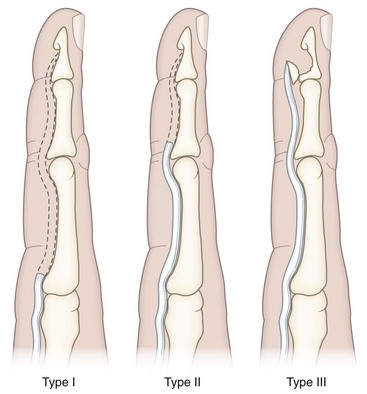

Leddy and Packer classified the FDP tendon avulsion injury in the finger into three types1 (Figure 20[A]-2):

Type I, the avulsed FDP tendon is retracted into the palm. The vincular system has been completely disrupted, resulting in loss of blood supply to the tendon.

Type I, the avulsed FDP tendon is retracted into the palm. The vincular system has been completely disrupted, resulting in loss of blood supply to the tendon.

Type II, the tendon retracts back to the level of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, being held there by the intact long vinculum.

Type II, the tendon retracts back to the level of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, being held there by the intact long vinculum.

Type III, there is usually a large bony fragment that is avulsed from distal phalanx and holds the tendon from proximal retraction by catching on the A4 pulley. The tendon and vinculae remain intact.

Type III, there is usually a large bony fragment that is avulsed from distal phalanx and holds the tendon from proximal retraction by catching on the A4 pulley. The tendon and vinculae remain intact.

Mansat and Bonnevialle2 have found it more logical to classify this injury according to the extent of retraction of the avulsed FDP tendon from a more benign form to a more severe form:

Type I, proximal retraction of the avulsed FDP tendon to the level of the bifurcation of the FDS tendon, but the long vinculum remains intact.

Type I, proximal retraction of the avulsed FDP tendon to the level of the bifurcation of the FDS tendon, but the long vinculum remains intact.

Type II, marked retraction of the avulsed FDP tendon into the palm, with avulsion of the vinculae and loss of the tendon vascular support.

Type II, marked retraction of the avulsed FDP tendon into the palm, with avulsion of the vinculae and loss of the tendon vascular support.

Type III, Intraarticular fracture of the distal phalanx and dorsal subluxation of the DIP joint; the tendon still attaches to the bony fragment and proximal retraction of the FDP tendon is very limited. The bony fragment is entrapped in the distal part the digital sheath tunnel.

Type III, Intraarticular fracture of the distal phalanx and dorsal subluxation of the DIP joint; the tendon still attaches to the bony fragment and proximal retraction of the FDP tendon is very limited. The bony fragment is entrapped in the distal part the digital sheath tunnel.

Type IV, the tendon is avulsed from the fractured fragment of the distal phalanx and retracts; the fracture is intraarticular, involving articular surface.15

Type IV, the tendon is avulsed from the fractured fragment of the distal phalanx and retracts; the fracture is intraarticular, involving articular surface.15

Type V, avulsion of an osseous fragment connecting to the insertion of the FDP tendon. There is a concomitant fracture of the distal phalanx beside the avulsion.16

Type V, avulsion of an osseous fragment connecting to the insertion of the FDP tendon. There is a concomitant fracture of the distal phalanx beside the avulsion.16

In some rare cases, both flexor tendons can be avulsed on the same finger.7–10

Diagnosis

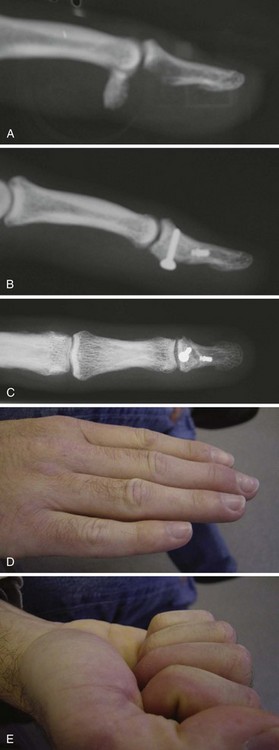

The problem of this injury is that it is often missed initially. In the Mansat and Bonnevialle series, only 50% of the cases had been diagnosed within the first 3 weeks.2 The history of the mechanism of injury is typical. While playing rugby, American football, or other sports, the patient feels a searing pain in the ring finger when grasping the opposite player’s jersey, sometimes with ecchymosis (Figure 20[A]-3). The patient may notice loss of active DIP joint flexion (or PIP joint flexion for an FDS tendon avulsion) (Figure 20[A]-4). Pain localization may give an indication of the amount of retraction of the avulsed tendon. According to Mansat and Bonnevialle’s classification,2 in type I, patients have pain, swelling, and loss of motion of the PIP joint as well as no active flexion of the DIP joint. In type II, the patient may have tenderness over the insertion area of the FDP tendon on the distal phalanx, and there also may be tenderness and swelling in the palm where the tendon has retracted. In type III, the patient has marked swelling, ecchymosis, and pain over the distal aspect of the middle phalanx just proximal to the DIP joint, as well as no active flexion at the DIP joint. Radiographs are often negative in type I and II lesions. However, in types III, IV, and V, a lateral radiograph shows a large bony fragment just proximal to the DIP joint with or without distal phalanx fracture (Figure 20[A]-5). The use of ultrasound has been proposed to localize the avulsed tendon.27 The only differential diagnosis is a torn volar plate of the DIP joint as described by Bowers and Fatjgenbaum.28

Figure 20(A)-4 Loss of active flexion of the DIP joint after rupture of the FDP tendon in a ring finger.

Figure 20(A)-5 A lateral x-ray film showing a bony fragment avulsed from the base of the distal phalanx.

Isolated, closed avulsion of the FDS tendon at its insertion can present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The injury is often associated with flexion deformity and diminished extension of the involved digit. This presentation is readily explained by the anatomy of the digital flexor tendon and annular pulley system. Once torn from its insertion on the middle phalanx, the superficialis tendon retracts proximally. It stops at the level of the A1 pulley where Camper’s chiasma acts as noose to ensnare the FDP tendon. If diagnosis is delayed, inflammation and adhesion formation further entrap the profundus tendon.5 Lateral radiograph can show a bony fragment at the middle phalanx.6

Treatment

Several factors have been identified which influence the prognosis and treatment of injury of the FDP tendon: (1) the level of retraction of the tendon, (2) the status of the vinculae, (3) the delay between injury and treatment, and (4) the presence and size of a phalangeal bony fragment.2,18

The definition of “acute” cases varies from one surgeon to another. For Mansat and Bonnevialle,2 a delay of 3 weeks is the limit, whereas for Tropet et al,3 10 days is the maximum. For Leddy and Packer,1 the delay is not the major factor but more the level of tendon retraction at diagnosis. If the tendon is not retracted, a direct repair can be performed up to 3 months after injury; on the other hand, if the tendon is retracted into the palm, direct repair may not be possible after 10 days have elapsed. Usually, final decision is made during surgery.

The treatment of an acute injury, according to Mansat and Bonnevialle’s classification,2 is described below. The decision to repair or reattach the tendon to the distal phalanx depends on the degree of retraction.

In type I, the optimal treatment for this injury is early reinsertion of the tendon to the distal phalanx. The exposure is through a zigzag incision on the finger, exposing the flexor sheath from the area of the insertion to just proximal to the PIP joint. An opening is created in the sheath just distal to the A2 pulley to identify the retracted tendon (Figure 20[A]-6). The tendon is found and threaded beneath the flexor tendon sheath to the level of the distal phalanx in a nontraumatic manner. A raised osteoperiosteal flap is then created at the insertion site on the distal phalanx, and the profundus tendon is reinserted. If some tendon materials remain on the distal phalanx direct tendon-to-tendon suture must be avoided because of a high risk of secondary rupture.4 Transosseous suture repair is preferred, using a standard pull-out wire and button technique,1,2 a double-arm reinsertion technique,29 or micro-anchors4,30 (Figure 20[A]-7). In the Brustein et al study,31 the micro-bone suture anchor provided a stronger tendon-to-bone repair compared to pull-out wire and button or a mini-anchor. However, McCallister et al32 have shown no difference between pull-out wire and button technique and mini-anchors for zone 1 flexor tendon repair in respect of clinical outcome, although significant improvement was found in the time to return to work following repairs using suture anchor technique. There was less potential morbidity associated with the anchor technique compared to the pull-out wire and button technique. The main problems reported with the pull-out technique were discomfort, pain, suture wire rupture, difficulty in daily care of the bolster, infection, skin necrosis, and nail bed injury.33 The use of a braided polyester suture instead of a monofilament suture is recommended, as it is more resistant to cyclic testing.34 Care should be taken not to injure the volar plate of the DIP joint when reinserting the tendon.

Figure 20(A)-7 Repair of the FDP tendon by means of pull-out or barb-wire suture (A), or micro-anchors (B).

In type II, the exposure is identical to that for a type I injury. If the tendon is not identified just distal to the A2 pulley, it must have retracted into the palm. Then, a slightly curved incision is made just proximal to the distal palmar crease; this allows exposure of the flexor sheath proximal to the A1 pulley. A small incision is made in the sheath, and the distal end of the profundus tendon is identified. Next, a small catheter is inserted into the sheath through the incision in the distal finger and passed to the level of the A1 pulley. The profundus tendon is then sutured to the catheter, which is pulled distally, threading the profundus tendon back beneath the pulleys and through the superficialis chiasma to the level of the PIP joint. The tendon is then passed in a similar fashion beneath the C1, A3, C2, A4, and C3 pulleys to the level of the distal phalanx. The tendon is reattached to the phalanx with the methods for a type I injury. However, if reinsertion on the phalanx is difficult and under tension, resection of the tendon with stabilization of the DIP joint in slight flexion is preferred. Using the distal remnant of the profundus tendon may help to create a simple tenodesis protected by a temporary K-wire. Fusion is an alternative to tenodesis.2

In type III, treatment consists of open reduction and internal fixation of the bone fragment. Correct reduction of the joint line is necessary to obtain good motion without pain. Internal fixation can be performed with K-wires,2,4,15,35,36 micro-screws,20,37,38 or a micro-plate39,40 (Figure 20[A]-8).

In types IV and V, the bony fragment is openly reduced and fixed followed by repair of the avulsed profundus tendon, as described for type I and II injuries, depending on the level of retraction.15,16

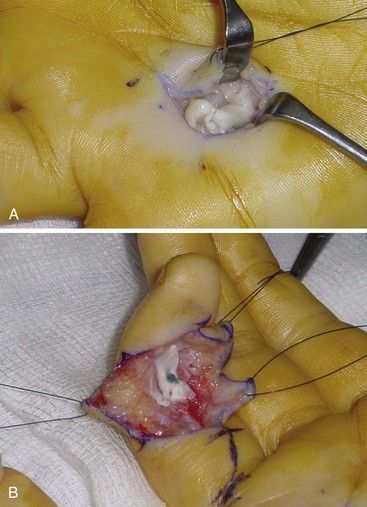

For old injuries, management is variable and individualized for each case. Decision-making is based on functional impairment (PIP joint stiffness, loss of strength), patient’s needs and expectation, and total ranges of active and passive motion of the PIP and DIP joints. Those patients who are asymptomatic should be left alone. Rarely do patients have limitation of motion at the PIP joint 6 months after injury; however, if there is instability of the DIP joint with weakness of pinch or recurrent dorsal dislocation, arthrodesis or tenodesis of the joint should be considered18 (Figure 20[A]-9). Fusion provides joint stability and does not interfere with the function of the superficialis tendon. If there is a tender lump in the palm, the retracted tendon end can be excised at the time of fusion. Generally, Mansat and Bonnevialle2 advocated (1) no surgery when impairment is slight (non-manual workers), the PIP joint is perfectly mobile, and the DIP joint is stable; and (2) simple resection of the retracted FDP tendon if the PIP joint is stiff, in association with tenodesis of the DIP joint. There is a risk of PIP and DIP joint stiffness if reinsertion is performed, even in type I injury. One-stage tendon graft with palmaris longus tendon should be reserved for patients for whom strength and function impairment of the ring finger are not acceptable but who have normal passive motion of PIP and DIP joints (Table 20[A]-1).

Figure 20(A)-9 Type I lesion treated by resection of the FDP tendon (A), and tenodesis of the remnant of the FDP tendon at the DIP joint (B).

Table 20(A)-1 Operative Methods for Avulsion of the FDP Tendon

| Type* | Operative Treatment: Acute (<3 Wk) | Operative Treatment: Late (>3 Wk) |

|---|---|---|

| I | Direct repair (+micro-anchors) | FDP resection + DIP joint capsulodesis or tenodesis |

| FDP resection + DIP joint capsulodesis or tenodesis | FDP resection + DIP joint arthrodesis | |

| FDP resection + DIP joint arthrodesis | Tendon graft | |

| II | Direct repair (+micro-anchors) | Direct repair (+micro-anchors) FDP resection + DIP joint capsulodesis or tenodesis FDP resection + DIP joint arthrodesis Tendon graft |

| III | Osteosynthesis (±suture of the tendon) | Osteosynthesis (±suture of the tendon) |

* Classifications by Leddy and Packer.1

FDS tendon avulsion can be reinserted or sutured totally or partially with repair of one slip through a palmar zigzag incision centered on the PIP joint if diagnosed early. However, for long-standing cases, the incision must be extended into the palm. The retracted end of the tendon is found at the level of the A1 pulley. Peritendinous adhesions and scar tissue were excised along with the FDS tendon.5 If a bony fragment is attached to the tendon, it is removed with the tendon.6

Postoperative Care

Postoperatively, in type I and II lesions after reinsertion of the FDP tendon to the distal phalanx, a dorsal splint is used to hold the wrist in slight flexion, the MCP joints in 75° of flexion, and the PIP and DIP joints in relative extension (Figure 20[A]-10). Passive flexion exercises are started early in the postoperative course. Active exercises are begun at 3 weeks when the splint is removed. The pull-out wire and button are removed 3 to 4 weeks postoperatively, and the remaining rehabilitation is similar to that for other flexor tendon injuries.

Figure 20(A)-10 Dorsal splinting to place the MCP joint in flexion and PIP and DIP joints in extension.

Outcomes

For acute lesions of the FDP tendon, surgical repair is always indicated, and satisfactory results varied from 70% for Gaston et al4 to 80% for Mansat and Bonnevialle2 and 100% for Leddy and Packer1 and Tropet et al.3 For type II lesions according to Mansat and Bonnevialle’s classification, reinsertion of the FDP tendon on the distal phalanx must be performed without tension to obtain satisfactory results.2 If not, the finger becomes stiff with limitation of active motion of the DIP and PIP joints. For type III, IV, and V lesions, the prognosis depends on the quality of articular surface reduction, often with loss of few degrees of active motion of the DIP joint.4

For chronic lesions, if the patient has no or slight impairment, conservative management is the best option. If the patient complains of digital pain, with flexion deficit of the PIP joint, resection of the avulsed tendon must be proposed. If there is instability of the DIP joint, capsulodesis, or arthrodesis of the DIP joint can be added. Tendon grafting should be limited to young and active patients with specific needs. Preoperative normal passive motion of the PIP and DIP joints is a prerequisite to a good result. The patient must be aware that a tendon graft usually does not allow complete recovery of DIP active flexion. McClinton et al,41 reviewing 100 cases of tendon graft for isolated FDP tendon laceration, obtained 48° of average DIP active flexion. Liu and Yang,42 reviewing 15 cases of tendon graft for isolated FDP tendon rupture, obtained an average of 33° of DIP active flexion. Main complications were loss of PIP joint extension (more than 30° in 27% of the cases of Liu et al,42 less than 10° in 55% of the cases, and more than 10° in 9% of the cases of McClinton et al41).

Our Personal Experience

We recently reviewed our experience of treating avulsion of the FDP tendon in 20 patients.4 These included 17 men and 3 women (average age, 31 years; range, 20 to 52 years). In 12 cases, the injury was related to sports injury (football or rugby), and in 8 cases, to domestic or work-related trauma. The ring finger was involved in 14 cases, the middle finger in 3 cases, and the little finger in 3 cases. In 14 cases the patients were seen within 3 weeks from the injury. According to Leddy and Packer’s classification,1 the lesion was staged as type I in 5 patients, type II in 6, and type III in 3. In 6 cases, the patient was seen more than 3 weeks from the initial trauma. These lesions were classified as type I in 5 and type II in 1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree