Chapter 4 The Temple and the Brow

The Temporal Fascia Layers, the Upper and Lower Temporal Compartments, and the Inferior Temporal Septum

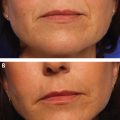

Temple hallowing is a common problem in the aging face, and nomenclature can be confusing. Volume lost with aging in the temple may be the result of atrophy of the temple fat pad, superficial lateral orbital fat, and lateral temporal cheek fat. The coined term temporal hollowing reflects deficiency in the temporal adipose and/or muscle. In accordance with this aging phenomenon, the more prominent skeletal contours adjacent to the temple can further diminish the perceived projection of the temple. As a general rule, authors advocate undercorrection compared to overcorrection for temporal contour (Video 4.1).

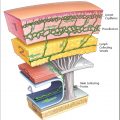

As the scalp layers converge into the temple, the galea aponeurotica becomes the superficial temporal fascia (synonymous with the temporoparietal fascia [TPF]); in contrast, the periosteum becomes synonymous with the deep temporal fascia. The deep temporal fascia is composed of separately named lamina (superficial and deep) at the level of the zygomatic arch. These laminae will fuse 2 to 3 cm cephalic to the zygomatic arch into one layer at the temporal line of fusion. A reproducible method to understanding the temporal anatomy is to divide the temporal into upper and lower temporal compartments. This has been refined and well described by Bryan Mendelson and his colleagues.

The upper temporal compartment is bordered superiorly by the superior temporal septum. This septum is the upper limit of the temple region. It is at this point that the periosteum converts to deep temporal fascia. The septum traverses anteriorly to the triangular temporal ligamentous adhesion (TLA). The TLA is a “keystone” that represents the convergence of the superior and inferior temporal septa. No vital structures exist in the superior temporal compartment and it is within the bounds of this space that the surgical dissector can visualize the straddling of the temporal fat compartment by the two laminae of deep temporal fascia.

The lower temporal compartment cephalic border is the inferior temporal septum. The compartment floor is comprised of dense fibrofatty parotid temporal fascia; this fascia condenses as it travels caudally to the lower zygoma merging with the zygomaticocutaneous ligaments and forming the relative inferior border of the compartment.

The deep fat compartment of the upper periorbital region is the retro-orbicularis oculi fat (ROOF) compartment. The fat resides deep in the orbicularis oculi muscle and galea. Deflation of this fat results in deep upper eyelid sulci and descent of the tail of the eyebrow.

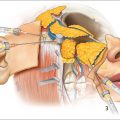

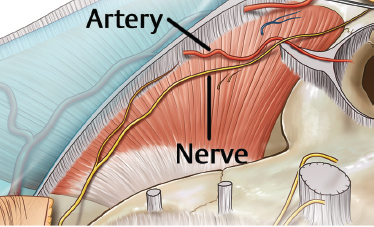

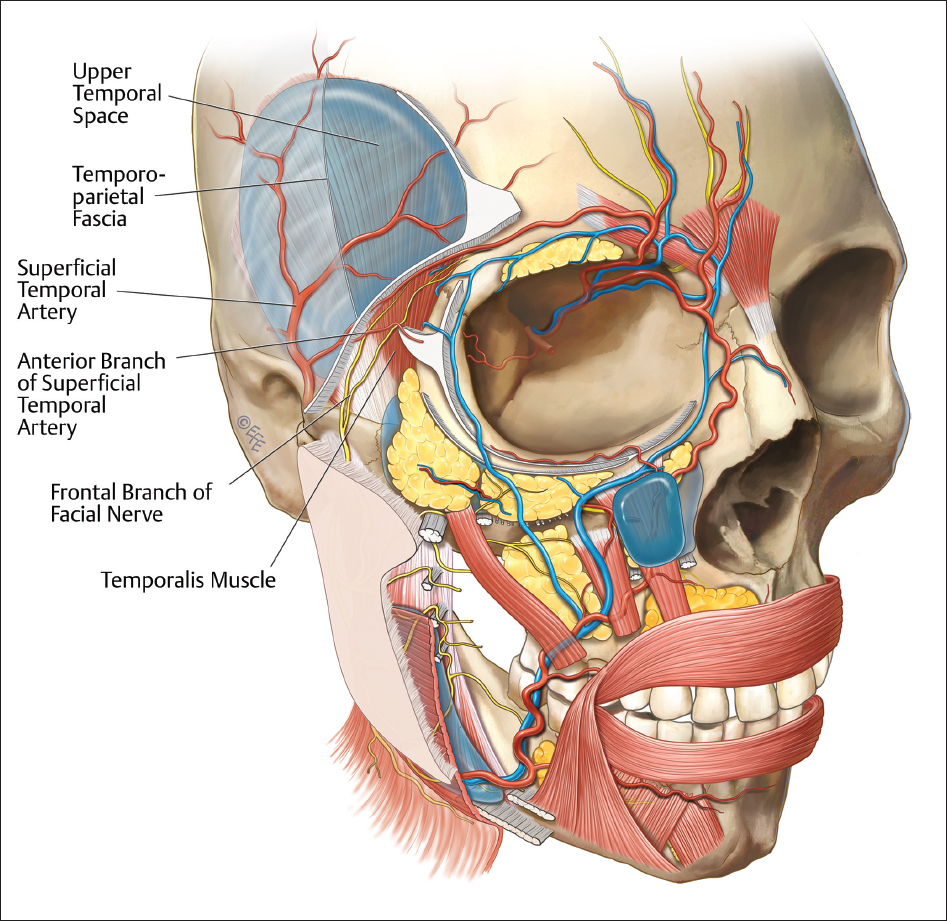

A thorough understanding of temple vascular anatomy is important to avoid undesirable complications. Three separate branches of the external carotid artery provide vascular supply within the temple region. The superficial temporal artery (STA) courses within the TPF. An anterior branch of the STA will run with the temporal rami of the facial nerve and often communicates with the supraorbital artery ( Fig. 4.1 ). Intravascular injection of this artery can result is retrograde thrombosis of the ophthalmic system and subsequent central retinal artery occlusion and blindness; therefore, superficial needle injection in the region should be performed with caution. Within the deep temporal fascia lie the middle temporal and deep temporal arteries. Of note, the deep temporal artery arises from the internal maxillary artery. Inadvertent injection into this artery can result in retrograde vascular occlusion and significant complications. As a result, we only recommend needle injections in the inferior medial quadrant of the temporal fossa (see section “The Authors’ Preferred Techniques for Temporal Volumization”). For the remainder of the temple, we recommend cannulas either in the upper temporal compartment, which is an avascular plane, or in the superficial temporal fat compartments.

Fig. 4.2 presents the gross anatomy of the neurovasculature and the upper temporal space.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree