Chapter 39 ONCOLOGIC RISKS OF FAT GRAFTING OF THE BREAST

The application of fat grafting has expanded beyond aesthetic indications and now is actively being explored for the treatment of cancer patients, especially those undergoing breast reconstruction after breast cancer treatment. 1 – 4 Fat grafting is indicated for local improvement after breast reconstruction, whatever the reconstructive method. It is also used to improve the results of conservative treatment. 5 It has been shown that fat grafting can improve the character of radiodystrophy lesions. 6 The simplicity of the technique and the fact that it produces no visible scars are just two of a plethora of reasons for the growing interest in this technique in the field of mammary reconstruction. Most published studies over several decades have focused on the technique and the excellent, permanent results. Concerns about the risk of microcalcifications observed on follow-up radiologic imaging have been widely explored, and most studies conclude that these calcifications are found to be benign in most instances, and experienced radiologists can generally distinguish these on imaging. 7 However, few studies have focused on the safety of fat grafting in patients who have been treated for cancer. 8 – 10

A number of published preclinical studies have considered whether adipose progenitor cells promote breast cancer growth and metastasis. In 2007 Vona-Davis and Rose 11 reported that white adipose tissue (WAT)–derived progenitor cells can contribute to tumor vessels, pericytes, and adipocytes, and were found to stimulate local and metastatic progression of breast cancer in several murine models. It is therefore essential to raise the question of the risk of recurrence for breast cancer patients who undergo a fat grafting procedure in the tissue surrounding a previous breast cancer treatment, particularly after conservative treatment.

Several years ago, the French Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (SOFCPRE) recommended that French plastic surgeons postpone fat grafting to the breast in patients with or without a breast cancer history unless the procedure is carried out under a prospective controlled protocol. 12 Today the document of the SOFCPRE given to patients states that “only a careful oncological follow-up will provide the assurance that such treatment cannot favor any mammary pathological lesion. Therefore the SOFCPRE recommends that the patient have regular mammograms and keep being followed regularly by her doctor.” In 2009 the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) set up the ASPS Fat Graft Task Force to assess the indications, safety, and efficacy of autologous fat grafting. 4 The task force noted that the question of cancer risk in the literature is based on a limited number of studies with few cases, with no control groups, based on expert opinion or case reports. Although no incontrovertible evidence of an increase in the risk of cancer recurrence from fat grafting has been observed or published, they cannot as yet provide definitive recommendations on the cancer risk associated with fat grafting.

The purpose of our two retrospective studies, conducted at our institute, the European Institute of Oncology (IEO) in Milan, was to evaluate the oncologic outcome of patients treated for breast cancer by conservative treatment or mastectomy, with or without radiotherapy and medical treatment, who underwent fat grafting for morphologic improvement of the breast. 9 , 10 The first study involved gathering a cohort with invasive and in situ types of breast cancer; the second study focused only on those with in situ cancers. These retrospective studies were matched to groups of patients without fat grafting to compare the risk of locoregional recurrence between the study group and the control group.

Material and Methods

FIRST STUDY

From the IEO Breast Cancer Database, we selected all the women who underwent surgery between 1997 and 2008 for primary breast cancer at the IEO. 9 We then identified all patients who subsequently underwent a fat grafting procedure for reconstructive purposes, who had no tumor recurrence between the primary surgery and fat grafting procedure. We excluded women with synchronous distant metastases at diagnosis, bilateral or recurrent tumor, previous cancer, and those receiving neoadjuvant treatment. We thus collected the cases of 321 consecutive patients. For each patient, we selected two matched patients with similar characteristics who did not undergo fat grafting.

SECOND STUDY

For the second study we selected, in the same population, the patients with in situ cancer and compared these cases with a matched population (1/2) of in situ patients who did not undergo fat grafting. 10 We analyzed 59 intraepithelial neoplasia patients who had undergone fat grafting, with no recurrence between primary surgery and fat grafting. A control group of 118 matched patients (two controls per fat grafting patient) with corresponding recurrence-free intervals was utilized. Both groups were also matched for their main cancer criteria. A local event (LE) was the primary endpoint, with follow-up starting from the baseline.

Results

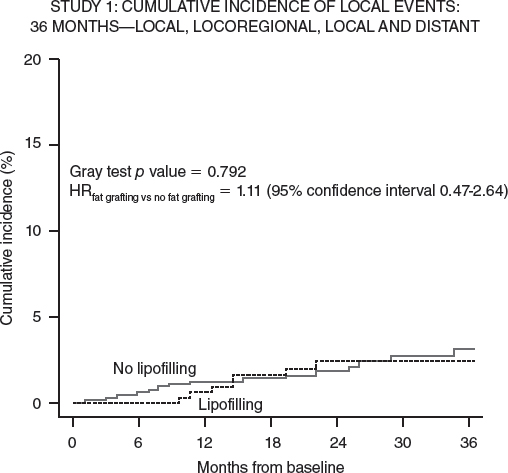

FIRST STUDY

Eighty-nine percent of the tumors were invasive. Median follow-up was 56 months from the primary surgery and 26 months from the fat grafting procedure. Eight and 19 patients had a local event in the fat grafting and control group, respectively, leading to comparable cumulative incidence curves (p = 0.792; hazard ratio: fat grafting versus no fat grafting = 1.11; 95% confidence interval 0.47 to 2.64). These results were confirmed when patients who had undergone quadrantectomy or mastectomy were analyzed separately and when the analysis was limited to invasive tumors, no statistical difference was seen. Analysis of a subgroup of patients with intraepithelial neoplasia showed a higher risk of locoregional recurrence in the study group, especially after conservative treatment (p = 0.04). Based on 37 cases, the fat grafting group demonstrated a higher risk of local events when the analysis was limited to intraepithelial neoplasia.

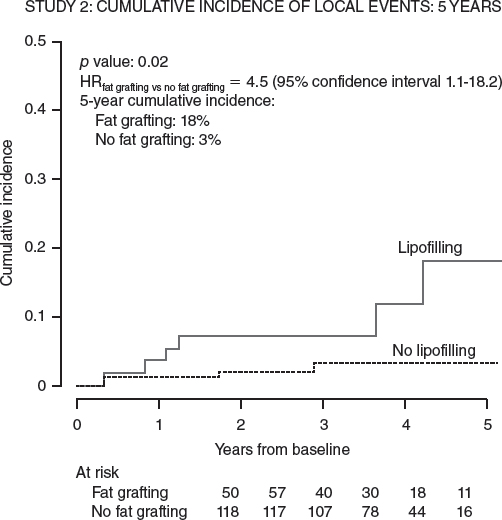

SECOND STUDY

The median follow-up in the second study was 63 and 66 months from surgery, and 38 and 42 from baseline, for the fat grafting and control groups, respectively. The 5-year cumulative incidence of LE was 18% and 3% (p = 0.02). A subgroup analysis showed that fat grafting did not statistically increase the risk of LE in women younger than 50 years of age, with-high grade neoplasia, Ki-67 of 14 or above, or who had undergone a quadrantectomy.

Both Milan studies showed an increased risk of locoregional recurrence in the group with in situ cancer who underwent fat grafting. 13

Complications

RECIPIENT SITE COMPLICATIONS

Fat necrosis, oil cyst formation, and calcifications can occur as a result of injecting large volumes of fat into a single area or injecting fat into poorly vascularized areas, resulting in failure of graft take. This leads to palpable mass formation resulting from fat necrosis, which may be difficult to distinguish clinically from a locoregional recurrence in breast cancer patients and require additional imaging and needle biopsy (3% to 15%). Moreover, calcification that occurs after fat grafting can be identified with mammography (0.7% to 4.9%). Infection occurs in 0.6% to 1.1% of fat grafted patients, and undercorrection or overcorrection of the deformity is another concern. Exceptional complications include damage to underlying structures such as breast implants, pneumothorax, and intravascular injection causing a fat embolism.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree