Chapter 28 STRUCTURAL FAT GRAFTING IN THE CHIN AND JAWLINE

Asculpted, well-contoured jawline is the hallmark of a youthful appearance, suggesting health, physical strength, and athletic prowess. It is the loss of definition of the mandibular border and chin that heralds the early signs of aging. With structural fat grafting, a jawline can be restructured to strengthen the border of the mandible and enlarge the chin. To reverse the signs of aging or to strengthen a weak mandible, it is important for the surgeon to understand how a youthful and strong mandible is composed (see Chapter 22).

Aesthetic Considerations

An appreciation of the form of an attractive, youthful chin and how it contrasts with an aging chin is essential for rejuvenation and enhancement of facial proportion. Only with that understanding can a surgeon control the shape of the chin or jaw to restore it to a more youthful or attractive appearance. 1 – 3

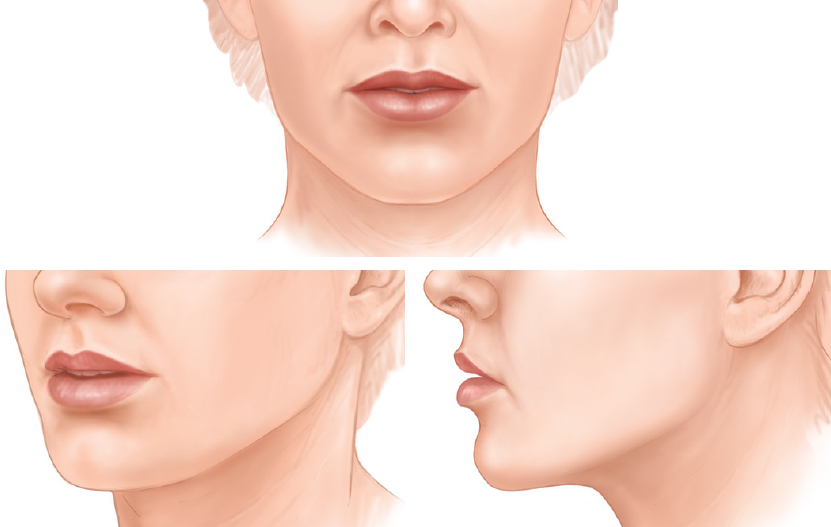

The contour of a young, healthy chin has a distinct shape consisting of two distinct lateral protuberances with a central flattening or a cleft. I refer to this topographic relationship as the “ball-ball” of the chin. The lateral bulges project forward more than the central flattened or depressed area; thus it is the lateral chin that establishes the anterior projection of the chin.

The distance between these two “balls” determines the shape of the chin. When they are close together, a more pointed chin results, with less flattening of the midline. When the prominences are far apart, as is typical in a young man, the separation creates a more angular chin with more midline definition. In many cases the midline definition can result in a cleft, especially in younger chins.

The chin ages primarily by losing lateral and inferior fullness while retaining central fullness. As lateral and inferior volume is lost from the aging mentum, a “button” emerges in the upper middle chin area. This residual central bulge projects forward on the chin to become the most anterior point of the aging chin. As the volume from the lateral and lower chin is lost, the chin becomes more pointed and the youthful curvature of the lower chin flattens out in an oblique path, dropping off from the new central point of projection down to the submentum.

Although the middle of the chin appears to protrude more, the atrophic lateral chin can sag laterally, creating an overall appearance of chin widening from a frontal view. From the side view the lower chin flattens out (at a slant), running from the central button down to the shortened border of the mandible.

As the youthful fullness of the chin is lost, the chin’s thin skin falls into creases. Sometimes these furrows will develop in areas where lateral fullness has diminished, but often their development is random, following no discernible pattern. These creases may project unintentional emotional expression on the person’s face, such as anger or frowning, which may in fact be the opposite of what the person is feeling.

The young, healthy mandibular border is full and strong and has a distinct lateral fullness cephalic to the most caudal extent of the border. It is this lateral fullness that is especially prominent posteriorly that catches the light to create a strong jawline shadow from the angle to the chin.

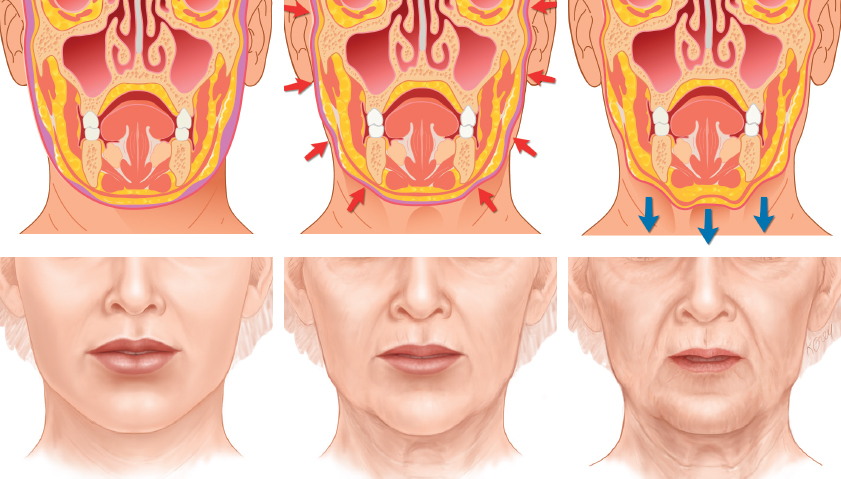

As in the rest of the face, generalized fullness between the skin and bones is lost with advancing age. As that underlying fullness is reduced, the face deflates. The enveloping sack of skin remains the same size, but without the underlying fullness and support. The emptied skin drapes around the underlying structures of the face exposing the facial muscles, the skull and many pockets of fat. This is a generalized loss of subcutaneous fullness, not a loss of fat.

A glance behind the mandible at the aging earlobe reveals a similar loss of volume, only with a different type of deflation. The earlobe resembles an empty balloon that hangs; this is a clear example of descent directly following atrophy.

Aging of the soft tissue covering of the mandible is a more complex process, but the primary mechanism is still deflation and radial entropy. As the soft tissues that frame the jawline disappear, the definition of the jawline becomes blunted. Without the lateral projection of fullness, the angle of the mandible loses its distinct shadow and appears to melt from the buccal region into the neck.

The largest collection of fat in the mandible is located at the jowl. This collection of fat is tethered with ligamentous attachments anteriorly. As the soft tissue fullness of the entire mandible recedes, the fat of the jowl, which was formerly obscured by surrounding fullness, emerges. In other words, the fat of the jowl and the skin are the most obvious stable soft tissue elements of the mandible, and the rest of the lower face disappears around it. The jowl does not descend, but instead the border of the mandible ascends, leaving the jowl below. Thus the face does not get longer but shorter with age. It effectively shortens from the lateral and oblique views.

As the jawline softens and retreats upward, the submental contents are exposed. The submaxillary gland and digastric muscles do not descend, but rather the jawline ascends to expose them. Likewise, as the jawline narrows with loss of fullness, the structural support that distracted the lower face laterally dissipates. A lack of support provided by the radial expansion by the soft tissue over the mandible allows the unsupported skin to be pulled downward by gravity. This downward movement is almost entirely secondary to a loss of radial support.

The young, healthy mandibular border is full and strong and has a distinct lateral fullness cephalic to the most caudal extent of the border. It is this lateral fullness that is especially prominent posteriorly that catches the light to create a strong jawline shadow from the angle to the chin.

Anatomic Considerations

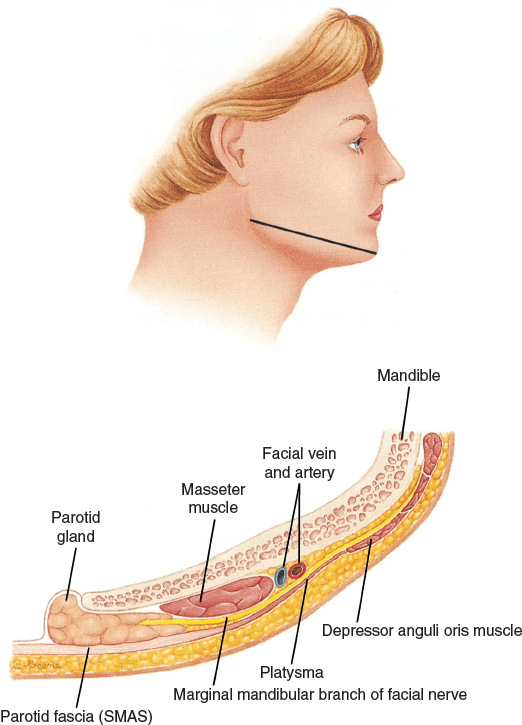

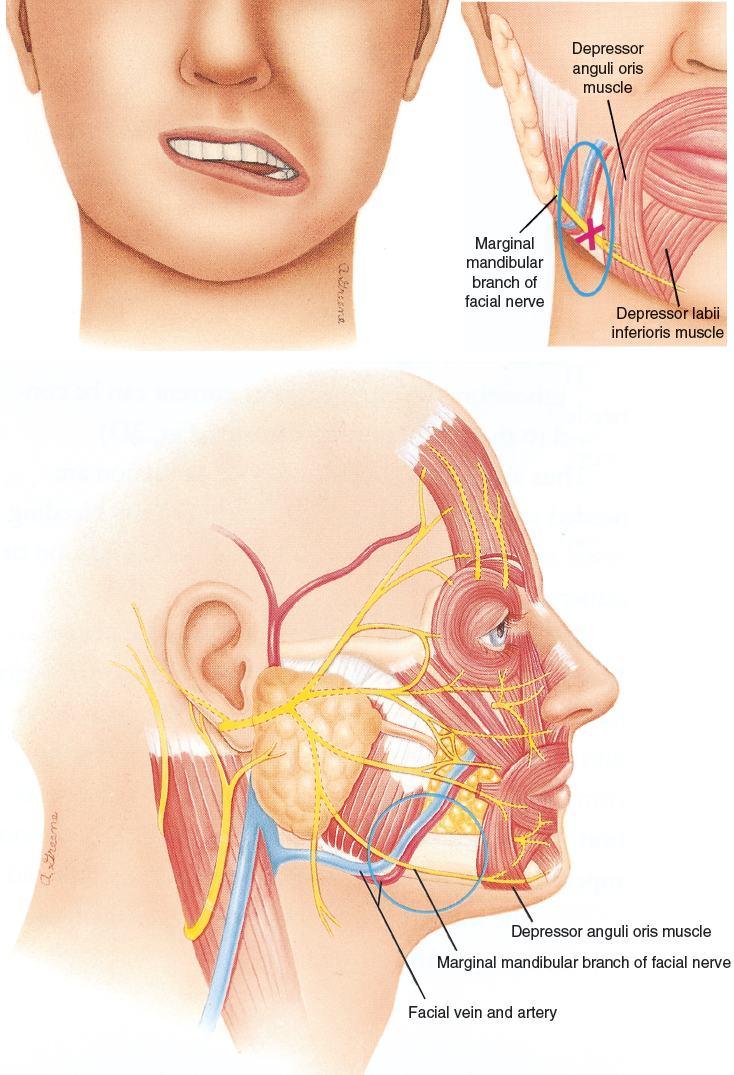

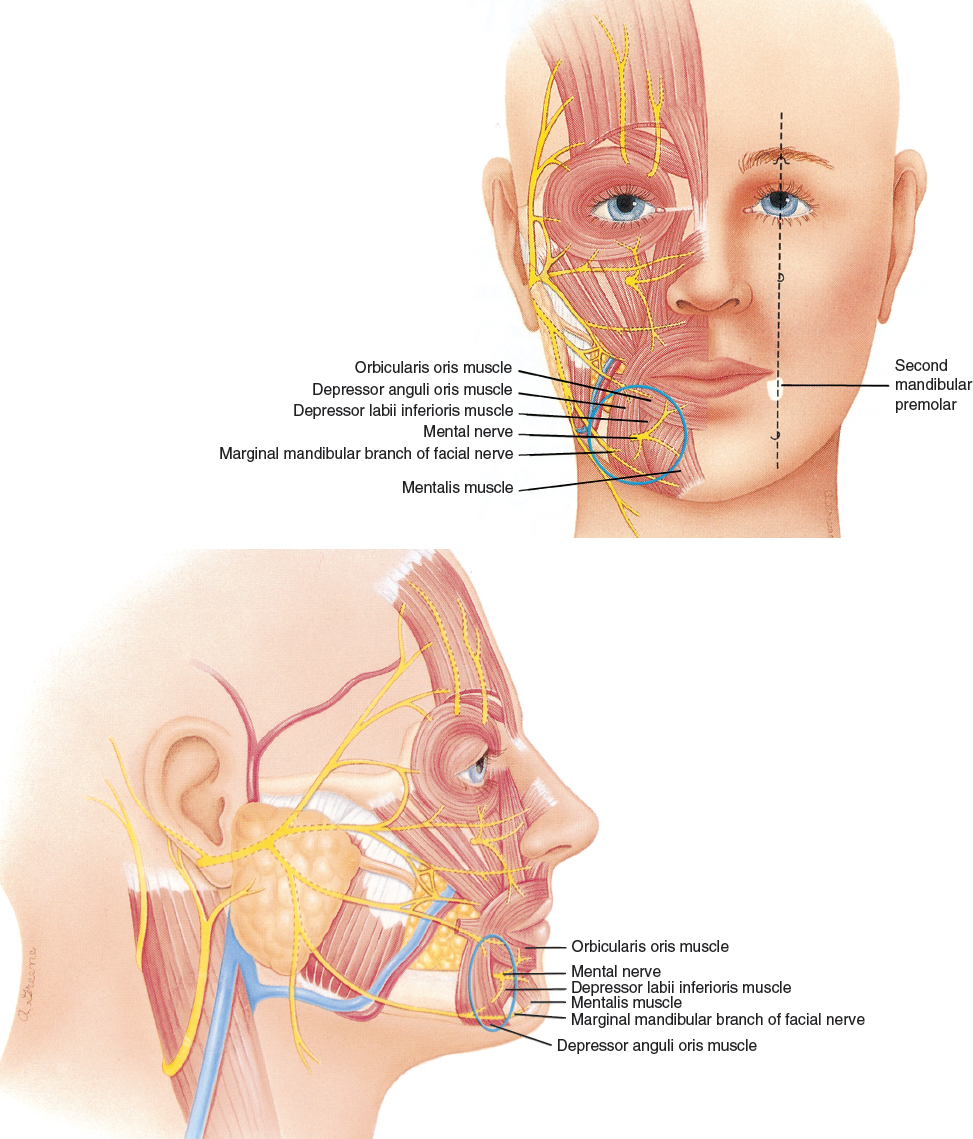

The positions of the major salivary glands, the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, the submental nerves, and the facial artery should be noted. Although none of my patients has had a permanent injury to any of these structures, there have been temporary injuries to all of them.

The parotid and submandibular glands should be respected in this region. To avoid perforating and potentially injuring the parotid gland, I do not graft fat into the deep planes of the mandible from the auricular or malar incisions, because I would have to perforate the parotid gland to place tissue that deep. For that reason, tissue is not placed into the deep planes against the bone of the posterior border of the mandible from any access site other than the border or midline incisions.

When the anterior border of the mandible is approached, I switch to the most blunt infiltration cannula to avoid injury to the marginal mandibular nerve. The injuries that I have experienced were all in conjunction with suctioning of the jowl area with a harvesting cannula attached to a 10 cc syringe; therefore I assume that the injury to the marginal mandibular nerve was most likely from the suction applied by the much larger suction cannula. For that reason, I now use a Coleman type I blunt infiltration cannula for removing any excess jowl fat, and I attach it to a much smaller 3 cc syringe.

When approaching the chin, I also try to switch to Coleman type I infiltration cannulas to avoid trauma to the mental nerves. No patient has complained about anesthesia in the chin, but a traumatic injury to this area is still a definite possibility, and all efforts should be made to avoid the problem.

The key to mandibular and chin placement is understanding the three-dimensional shape of an attractive mandibular border and chin to create a strong, appropriately shaped mandibular border with a submandibular shadow. To accomplish this goal, the “ball-ball” structure of the attractive chin must also be reproduced.

The jawline can be restructured to strengthen the border of the mandible and enlarge the chin, thereby changing facial proportion to project a more cleanly sculpted profile.

Indications and Patient Selection

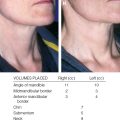

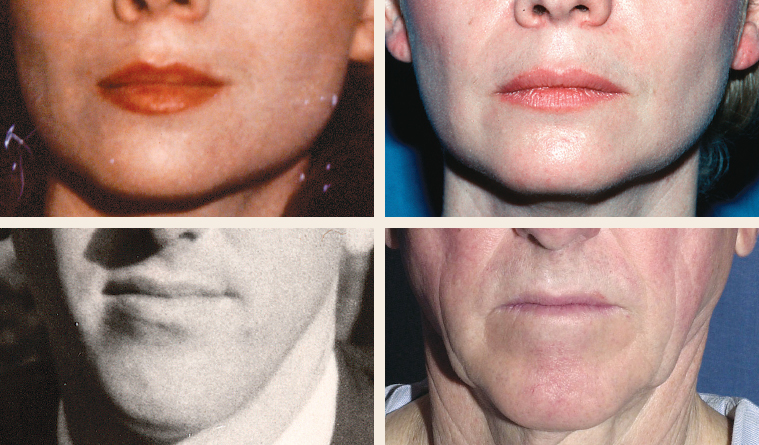

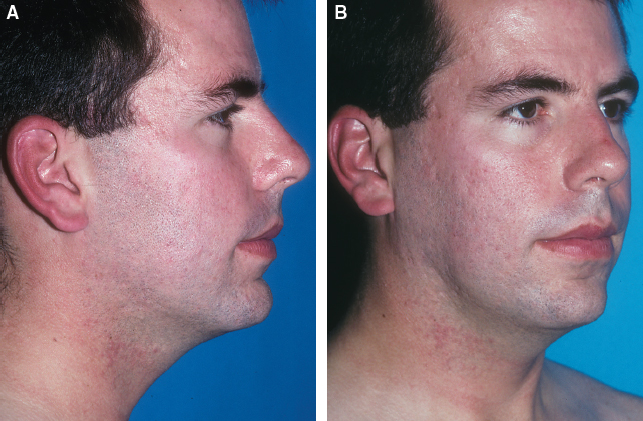

The first patients to present in my practice requesting mandibular strengthening were young men and women, such as this patient, who simply wanted a slightly stronger mandibular border. This young man came to my office in 1987 requesting augmentation of his jawline and lateral brow. His result is shown 7 years after one procedure to those two areas. He also had augmentation of his anterior malar area.

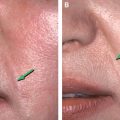

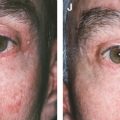

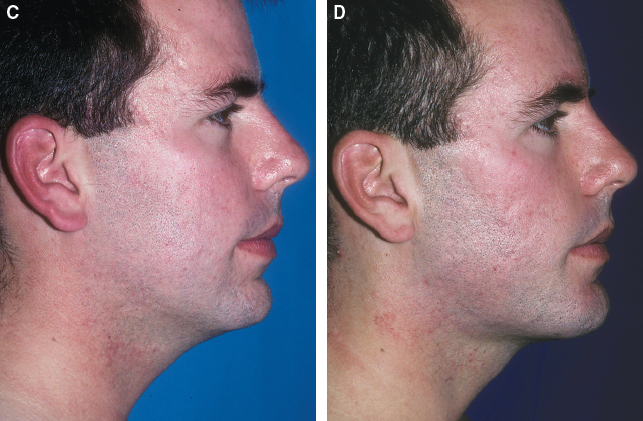

Chronic acne destroyed the mandibular border of this 28-year-old man. He is an excellent example of how loss of structure in the chin and jawline can produce a sickly, portly appearance, even in a young person.

A decade of cystic acne had destroyed the subcutaneous tissue of his chin and jawline. With loss of the subcutaneous tissues that frame the bony mandible, the border from the chin to the angle had become poorly defined and the radial vectors that normally support the overlying skin were no longer present, so the unsupported skin of the lower face was pulled downward by gravity.

The patient is shown 1 year after structural augmentation of his chin, jawline, cheeks, and temples. The only procedure performed was structural fat grafting; no tissue was removed from his face. This case dramatically highlights the principle that in structural fat grafting, the difference between unattractive and handsome is only a few millimeters.

Adding only a few millimeters of structure to the jawline and chin has reframed his mandible so that it is now clearly delineated. Lowering the mandibular border hides a portion of the submental contents and the radial vector; expanding the jaw distracts the submental excess laterally, resulting in a dramatic change in facial proportion.

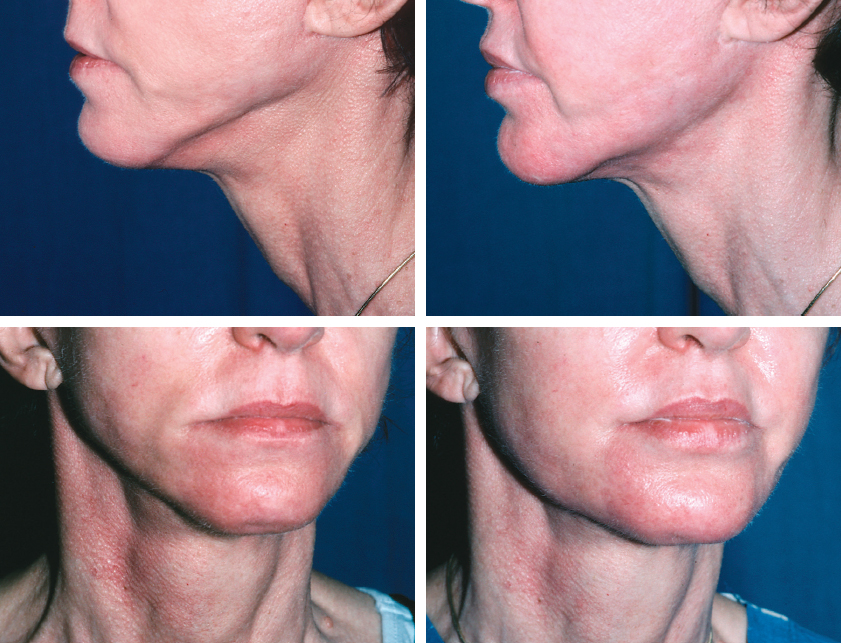

Patients who feel that their mandibular borders are poorly defined are good candidates for augmentation of the mandible and chin. The most common reasons that people seek this correction are aging and iatrogenic deformities after facelifts, as was the case with this woman, who presented after a facelift left her with a much-elevated jawline that exposed her submental contents. She is shown 13 months after restructuring of her mandibular border with structural fat.

Although the primary reason for fat grafting in the chin has been for augmenting and reshaping the chin, irregularities, asymmetries, and ptosis are also indications for structural augmentation of the chin. Reconstructive indications include secondary or even primary treatment of maxillofacial and craniofacial deformities, along with restoration of mandibular soft tissue lost from trauma or neck dissections and a large variety of mental deformities. Caution should be exercised when strengthening the mandibular borders in women, because it is easy to create a jawline that is too powerful or masculine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree