8 Blepharoplasty

Synopsis

Blepharoplasty is a vital part of facial rejuvenation. The traditional removal of tissue may or may not be the preferred approach when assessed in relation to modern cosmetic goals.

Blepharoplasty is a vital part of facial rejuvenation. The traditional removal of tissue may or may not be the preferred approach when assessed in relation to modern cosmetic goals.

A thorough understanding of orbital and eyelid anatomy is necessary to understand aging in the periorbital region, and to devise appropriate surgical strategies.

A thorough understanding of orbital and eyelid anatomy is necessary to understand aging in the periorbital region, and to devise appropriate surgical strategies.

Preoperative assessment includes a review of the patient’s perceptions, assessment of the patient’s anatomy, and an appropriate medical and ophthalmologic examination.

Preoperative assessment includes a review of the patient’s perceptions, assessment of the patient’s anatomy, and an appropriate medical and ophthalmologic examination.

Surgical techniques in blepharoplasty are numerous and should be tailored to the patient’s own unique anatomy and aesthetic diagnosis.

Surgical techniques in blepharoplasty are numerous and should be tailored to the patient’s own unique anatomy and aesthetic diagnosis.

Interrelated anatomic structures including the brow and the infraorbital rim may need to be surgically addressed for an optimal outcome.

Interrelated anatomic structures including the brow and the infraorbital rim may need to be surgically addressed for an optimal outcome.

Introduction

One should first conceptualize the desired outcome, then select and execute procedures accurately designed to achieve those specific goals. For this task to be accomplished, several important principles are advocated (Box 8.1). Enthusiastically embraced, this approach is likely to result in excellent aesthetic quality of surgical outcomes.

Box 8.1

Principles for restoration of youthful eyes

• Control of periorbital aesthetics by proper brow positioning, corrugator muscle removal, and lid fold invagination when beneficial.

• Restoration of tone and position of the lateral canthus and, along with it, restoration of a youthful and attractive intercanthal axis tilt.

• Restoration of the tone and posture of the lower lids.

• Preservation of maximal lid skin and muscle (so essential to lid function and aesthetics) as well as orbital fat.

• Lifting of the midface through reinforced canthopexy, preferably enhanced by composite malar advancement.

• Correction of suborbital malar grooves with tear trough (or suborbital malar) implants, obliterating the deforming tear trough (bony) depressions that angle down diagonally across the cheek, which begin below the inner canthus.

• Control of orbital fat by septal restraint or quantity reduction.

• Removal of only that tissue (skin, muscle, fat) that is truly excessive on the upper and lower lids, sometimes resorting to unconventional excision patterns.

• Modification of skin to remove prominent wrinkling and excision of small growths and blemishes.

History

As far back as the 10th and 11th centuries, Arabian surgeons, Avicenna and Ibn Rashid, described the significance of excess skin folds in impairing eyesight.1 Even at an early date, surgeons had excised upper eyelid skin to improve vision. Texts published in the 18th and 19th centuries were the first to describe and illustrate the upper eyelid aging deformities. The term, blepharoplasty, was coined by Von Graefe in 1818 to describe reconstructive procedures employed following oncologic excisions. Several European surgeons developed reconstructive techniques for eyelid defects in the latter half of the 19th century. Graefe and Mackenzie would be credited with applying these reconstructive principles and publishing the first, reproducible cases of upper blepharoplasty. The concepts of herniated orbital fat pads were described shortly thereafter by Sichel and Bourguet, respectively. Orbital fat pads were originally considered to be “circumscribed tumors” of fat that made movement of the upper lid more difficult. It was a rare condition found “most often in children”. Cosmetic blepharoplasty entered a period of rapid growth and research in the 1920–1930s. Contributions were made that described nearly 13 different approaches and closure methods. Recent variations in technique appear to have a basis in these early techniques, which have cycled in popularity over the last decade.

Basic science/disease process

Essential and dynamic anatomy

It is an absolute necessity that the surgeon understands the essential and dynamic periorbital anatomy to effect superior aesthetic and functional surgical results. No surgeon should perform surgery without fully understanding the aesthetic and functional consequences of the choices.2–5

Osteology and periorbita

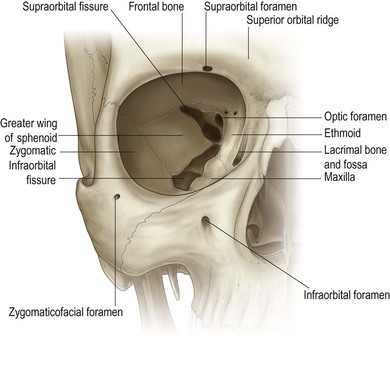

The orbits are pyramids formed by the frontal, sphenoid, maxillary, zygomatic, lacrimal, palatine, and ethmoid bones (Fig. 8.1). The periosteal covering or periorbita is most firmly attached at the suture lines and the circumferential anterior orbital rim. The investing orbital septum in turn attaches to the periorbita of the orbital rim, forming a thickened perimeter known as the arcus marginalis. This structure reduces the perimeter and diameter of the orbital aperture and is thickest in the superior and lateral aspects of the orbital rim.6

Certain structures must be avoided during upper lid surgery. The lacrimal gland, located in the superolateral orbit deep to its anterior rim, often descends beneath the orbital rim, prolapsing into the postseptal upper lid in many persons. During surgery, the gland can be confused with the lateral extension of the central fat pad destined for removal during aesthetic blepharoplasty. The trochlea is located 5 mm posterior to the superonasal orbital rim and is attached to the periorbital. Disruption of this structure can cause motility problems.7

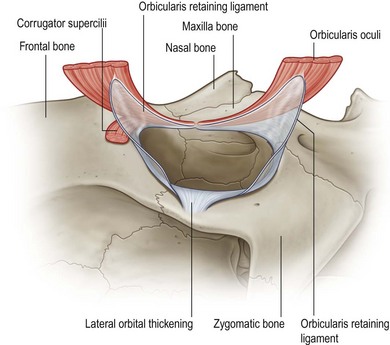

Lateral retinaculum

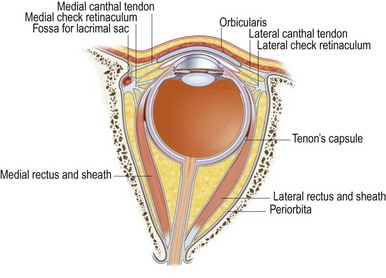

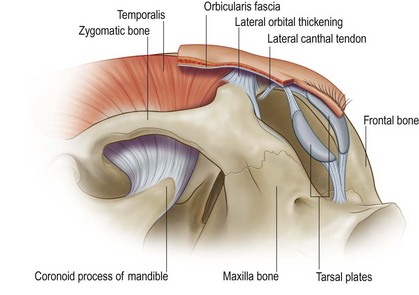

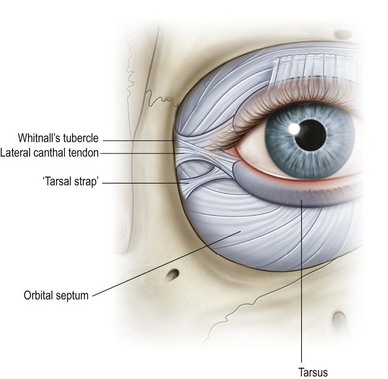

Anchored to the lateral orbit is a labyrinth of connective tissues that are crucial to maintenance of the integrity, position, and function of the globe and periorbital. Understanding how to effectively restore these structures is key to periocular rejuvenation by canthopexy. These structures, known as the lateral retinaculum, coalesce at the lateral orbit and support the globe and eyelids like a hammock (Fig. 8.2).8–10 The lateral retinaculum consists of the lateral canthal tendon, tarsal strap, lateral horn of the levator aponeurosis, the Lockwood suspensory ligament, Whitnall’s ligament, and check ligaments of the lateral rectus muscle. They converge and insert securely into the thickened periosteum overlying the Whitnall tubercle. Controversy exists surrounding the naming of the components of the lateral canthal tendon. Recent cadaveric dissections suggest that the lateral canthal tendon has dual insertions. A superficial component is continuous with the orbicularis oculi fascia and attaches to the lateral orbital rim and deep temporal fascia by means of the lateral orbital thickening. A deep component connects directly to the Whitnall tubercle is classically known as the lateral canthal tendon (Fig. 8.3).11

In addition, the tarsal strap is a distinct anatomic structure that inserts into the tarsus medial and inferior to the lateral canthal tendon.12 In contrast to the canthal tendon, the thick tarsal strap is relatively resistant to laxity changes seen with aging. The tarsal strap attaches approximately 3 mm inferiorly and 1 mm posteriorly to the deep lateral canthal tendon, approximately 4–5 mm from the anterior orbital rim. It shortens in response to lid laxity, benefiting from release during surgery to help achieve a long-lasting restoration or elevation canthopexy (Fig. 8.4). Adequate release of the tarsal strap permits a tension-free canthopexy, minimizing the downward tethering force of this fibrous condensation. This release along with a superior reattachment of the lateral canthal tendon is key to a successful canthopexy.

Medial orbital vault

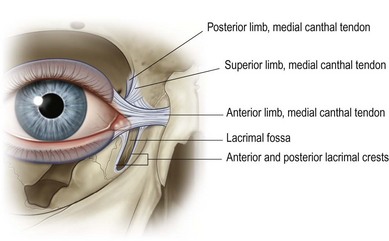

A hammock of fibrous condensations suspends the globe above the orbital floor. The medial components of the apparatus include medial canthal tendon, the Lockwood suspensory ligament and check ligaments of the medial rectus. The medial canthal tendon, like the lateral canthal tendon, has separate limbs that attach the tarsal plates to the ethmoid and lacrimal bones.13 Each limb inserts onto the periorbital of the apex of the lacrimal fossa. The anterior limb provides the bulk of the medial globe support (Fig. 8.5).

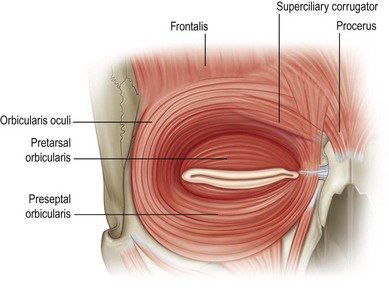

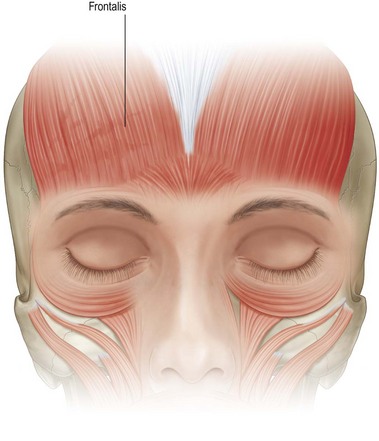

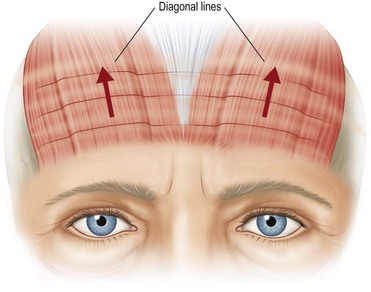

Forehead and temporal region

The forehead and brow consist of four layers: skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and galea. There are four distinct brow muscles: frontalis, procerus, corrugator superciliaris, and orbicularis oculi (Fig. 8.6). The frontalis muscle inserts predominately into the medial half or two-thirds of the eyebrow (Fig. 8.7), allowing the lateral brow to drop hopelessly ptotic from aging, while the medial brow responds to frontalis activation and elevates, often excessively in its drive to clear the lateral overhand. Constant contraction of the frontalis will give the appearance of deep horizontal creases in the forehead (Fig. 8.8).3

The obliquely oriented corrugators muscle arises from the frontal bone and inserts into the brow tissue laterally, with some extensions into orbicularis and frontalis musculature, forming vertical glabellar furrows during contraction. Wrinkles from procerus and corrugators contraction can worsen significantly after upper lid tissue excision as a result of the frontalis muscle’s relaxing after being relieved of the need to clear the obstructing lid skin.14

Eyelids

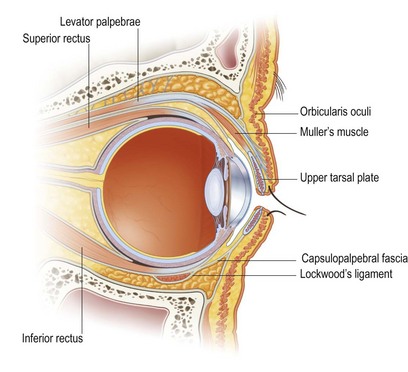

There is much similarity between upper and lower eyelid anatomy. Each consists of an anterior lamella of skin and orbicularis muscle and a posterior lamella of tarsus and conjunctiva (Fig. 8.9).15

The orbicularis muscle, which acts as a sphincter for the eyelids, consists of orbital, preseptal, and pretarsal segments. The pretarsal muscle segment fuses with the lateral canthal tendon and attaches laterally to Whitnall tubercle. Medially it forms two heads, which insert into the anterior and posterior lacrimal crests (Fig. 8.6).

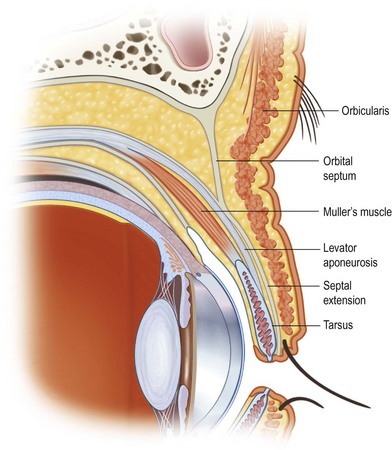

Upper eyelid

The levator palpebrae superioris muscle originates above the annulus of Zinn. It extends anteriorly for 40 mm before becoming a tendinous aponeurosis below Whitnall’s ligament.7,16 The aponeurosis fans out medially and laterally to attach to the orbital retinacula. The aponeurosis fuses with the orbital septum above the superior border of the tarsus and at the caudal extent of the sling, sending fibrous strands to the dermis to form the lid crease. Extensions of the aponeurosis finally insert into the anterior and inferior tarsus. As the levator aponeurosis undergoes senile attenuation, the lid crease rises into the superior orbit from its remaining dermal attachments while the lid margin drops.

Müller’s muscle, or the supratarsal muscle, originates on the deep surface of the levator near the point where the muscle becomes aponeurotic and inserts into the superior tarsus. Dehiscence of the attachment of the levator aponeurosis to the tarsus results in an acquired ptosis only after the Müller’s muscle attenuates and loses its integrity.14

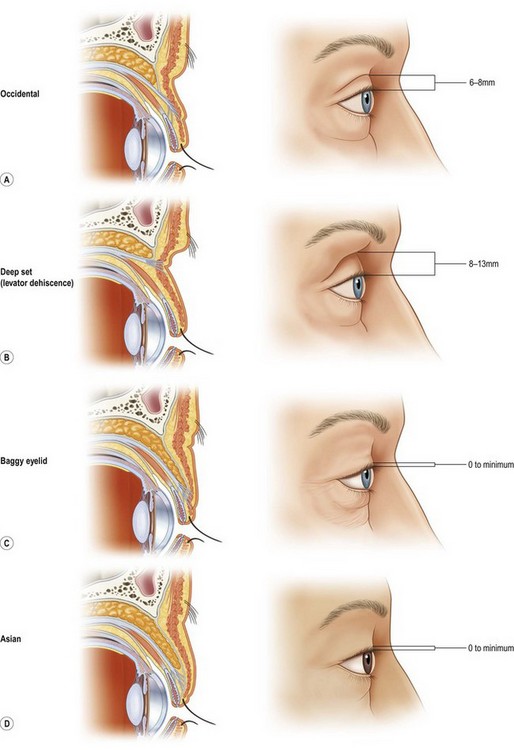

In the Asian eyelid, fusion of the levator and septum commonly occurs at a lower level, allowing the sling and fat to descend farther into the lid.15,16 This lower descent of fat creates the characteristic fullness of their upper eyelid. In addition, the aponeurotic fibers form a weaker attachment to the dermis, resulting in a less distinct lid fold (Fig. 8.10).

Septal extension

The orbital septum has an adhesion to the levator aponeurosis above the tarsus. The septum continues beyond this adhesion and extends to the ciliary margin. It is superficial to the preaponeurotic fat found at the supratarsal crease. The septal extension is a dynamic component to the motor apparatus, as traction on this fibrous sheet reproducibly alters ciliary margin position (Fig. 8.11). The septal extension serves as an adjunct to, and does not operate independent of, levator function, as mistaking the septal extension for levator apparatus and plicating this layer solely results in failed ptosis correction.17

Lower eyelid

The anatomy of the lower eyelid is somewhat analogous to that of the upper eyelid. The retractors of the lower lid, the capsulopalpebral fascia, correspond to the levator above. The capsulopalpebral head splits to surround and fuse with the sheath of the inferior oblique muscle. The two heads fuse to form the Lockwood suspensory ligament, which is analogous to Whitnall’s ligament. The capsulopalpebral fascia fuses with the orbital septum 5 mm below the tarsal border and then inserts into the anterior and inferior surface of the tarsus.18 The inferior tarsal muscle is analogous to Muller’s muscle of the upper eyelid and also arises from the sheath of the inferior rectus muscle. It runs anteriorly above the inferior oblique muscle and also attaches to the inferior tarsal border.

The combination of the orbital septum, orbicularis, and skin of the lower lid acts as the anterior barrier of the orbital fat. As these connective tissue properties relax, the orbital fat is allowed to herniate forward, forming an unpleasing, full lower eyelid. This relative loss of orbital volume leads to a commensurate, progressive hollowing of the upper lid as upper eyelid fat recesses.19

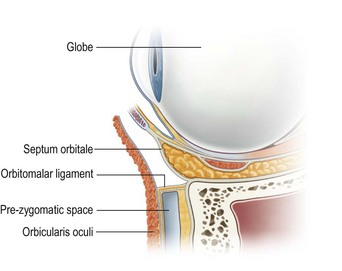

Retaining ligaments

A network of ligaments serves as a scaffold for the skin and subcutaneous tissue surrounding the orbit. The orbital retaining ligament directly attaches the orbicularis at the junction of its orbital and preseptal components to the periosteum of the orbital rim and, consequently, separates the prezygomatic space from the preseptal space. This ligament is continuous with the lateral orbital thickening, which inserts onto the lateral orbital rim and deep temporal fascia. It also has attachments to the superficial lateral canthal tendon (Figs 8.3, 8.12, 8.13).20 Attenuation of these ligaments permit descent of orbital fat onto the cheek. A midfacelift must release these ligaments to achieve a supported, lasting lift.21

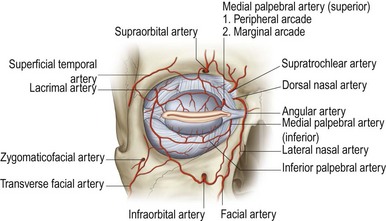

Blood supply

The internal and external carotid arteries supply blood to the orbit and eyelids (Fig. 8.14). The ophthalmic artery is the first intracranial branch of the internal carotid; its branches supply the globe, extraocular muscles, lacrimal gland, ethmoid, upper eyelids, and forehead. The external carotid artery branches into the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries. The infraorbital artery is a continuation of the maxillary artery and exits 8 mm below the inferomedial orbital rim to supply the lower eyelid.22

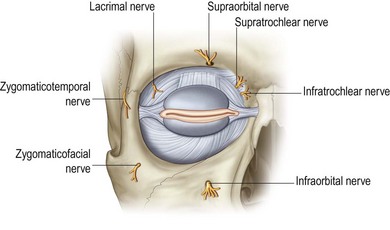

Innervation: trigeminal nerve and facial nerve

The trigeminal nerve along with its branches provides sensory innervations to the periorbital region (Fig. 8.15). The ophthalmic division enters the orbit and divides into the frontal, nasociliary, and lacrimal nerves. The terminal branch of the nasociliary nerve, the infratrochlear nerve, supplies the medial conjunctiva, and lacrimal sac. The lacrimal nerve supplies the lateral conjunctiva and skin of the lateral upper eyelid. The frontal nerve, the largest branch, divides into the supraorbital and supratrochlear branches. The supraorbital nerve exits through either a notch or a foramen and provides sensory innervations to the skin and conjunctiva of the upper eyelid and the scalp. The supratrochlear nerve innervates the skin of the glabella, forehead, medial upper eyelid, and medial conjunctiva. A well-placed supraorbital block will anesthetize most of the upper lid and the central precoronal scalp.6,14,23

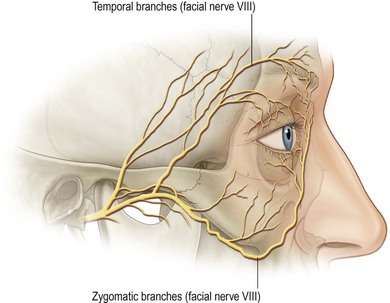

The facial nerve exits the stylomastoid foramen and divides in the substance of the parotid gland into the superior temporofacial and inferior cervicofacial branches (Fig. 8.16). The temporofacial nerve divides into the frontal, zygomatic, and buccal nerves; the cervicofacial nerve divides into the buccal, mandibular, and cervical nerves. There are significant variations in the branching of the facial nerve, which is responsible for facial expression. Innervation of facial muscles occurs on their deep surfaces. Interruption of the branches to the orbicularis muscle from the periorbital surgery or facial surgery may result in atonicity due to partial denervation of the orbicularis with loss of lid tone or anomalous reinnervation and possibly undesirable eyelid twitching.15

The frontal branch of the facial nerve courses immediately above and attached to the periosteum of the zygomatic bone. It then courses medially approximately 2 cm above the superior orbital rim to innervate the frontalis, corrugators, and procerus muscles from their deep surface. A separate branch travels along the inferior border of the zygoma to innervate the inferior component of orbicularis oculi.24 The surgeon should take great care when operating in this area to avoid damaging this nerve during endoscopic and open brow lifts.

Youthful, beautiful eyes

The characteristics of youthful, beautiful eyes differ from one population to another but generalizations are possible and provide a needed reference to judge the success of various surgical maneuvers. Attractive, youthful eyes are bright eyes. Bright eyes have globes framed in generously sized horizontal apertures (from medial and lateral), often accentuated by a slight upward tilt of the intercanthal axis (Fig. 8.17). The aperture length should span most of the distance between the orbital rims. In a relaxed forward gaze, the vertical height of the aperture should expose at least three-quarters of the cornea with the upper lid extending down at least 1.5 mm below the upper limbus (the upper margin of the cornea) but no more than 3 mm. The lower lid ideally covers 0.5 mm of the lower limbus but no more than 1.5 mm.4,15

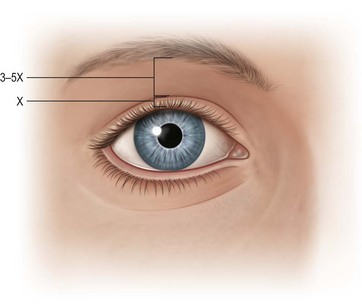

In the upper lid, there should be a well-defined lid crease lying above the lid margin with lid skin under slight stretch, slightly wider laterally. Ideally, the actual pretarsal skin visualized on relaxed forward gaze ranges from 3 to 6 mm in European ethnicities. The Asian lid crease is generally 2–3 mm lower, with the distance from lid margin diminishing as the crease moves toward the inner canthus. Patients of Indo-European and African decent show 1 to 2 mm lower than European ethnicities. The ratio of distance from the lower edge of the eyebrow (at the center of the globe) to the open lid margin to the visualized pretarsal skin should never be less than 3–1 (Fig. 8.1), preferably more.

The intercanthal axis is normally tilted slightly upward (from medial to lateral) in most populations. Exaggerated tilts are encountered in some Asian, Indo-European and African-American populations. Such upward tilt of the lateral canthal axis may give the eye a youthful appearance, which is aesthetically pleasing in any ethnic group. The lower lid that droops in its lateral aspect and the eye with a downward tilt generally convey to the viewer an aging, ill-health distortion or unattractiveness.25

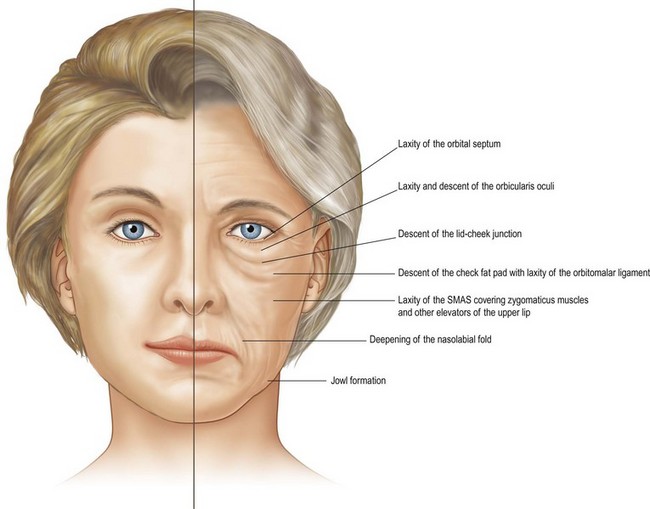

Etiology of aging

The etiology of aging changes in the lower lids is similar in some ways but quite different in others. Aging changes include relaxation of the tarsal margin with scleral show, rhytides of the lower lid, herniated fat pads resulting in bulging in one or all of the three fat pocket areas, and hollowing of the nasojugal groove and lateral orbital rim areas. Hollowing of the nasojugal groove area appears as dark circles under the eyes, mostly because of lighting and the shadowing that result from this defect (Fig. 8.18).26 It is clear that evaluation of all aspects of aging changes in the lids is important so the surgeon can plan the most effective operative procedure.

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Evaluation basics

The first essential step is to look at the patient carefully, thoroughly, and critically. The surgeon should be seated directly in front of the prospective patient with the patient’s eyes at his or her eye level. Note the general impression and feeling generated from looking at this person (Fig. 8.19).

Medical and ophthalmic history

A thorough history and physical examination should be performed before surgery (Box 8.2). In addition, an adequate eye history encourages positive outcomes and reduces eye complications.

Box 8.2

Important information to obtain during history and physical examination

• Medication use: particularly anticoagulants, anti-inflammatory and cardiovascular drugs, and vitamins (especially vitamin E).

• Herbal supplement use: herbs represent risks to anesthesia and surgery, particularly those affecting blood pressure, blood coagulation, the cardiovascular system, and healing.

• Allergies: medication and type.

• Past medical history: especially hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, hepatitis, liver disease, heart disease or arrhythmias, cancer, thyroid disease, and endocrine disease.

• Bleeding disorders or blood clots.

• Alcohol and smoking history.

• Recreational drug use, which may interact with anesthesia.

• Exposure to human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis virus.

Contact lens wear poses particular risks when eyelid surgery is performed. The natural progression of aging dries the eyes out, and long-term contact lens wearing hastens this process considerably. Traditional blepharoplasty techniques consistently produce vertical dystopia with increased scleral exposure, making the lens wear difficult if not dangerous. Ptosis and canthopexy surgery may alter the corneal curvature and require that contacts be refitted. The patient should discontinue contact lens wear in the perioperative period to allow healing without the need to manipulate the eyelids. Levator dehiscence or attenuation commonly accompanies long-term hard contact lens wear, caused by the mechanical stresses posteriorly from the rigid lens rubbing against the posterior lamella of the lid.27

The same population that seeks aesthetic surgery also gravitates toward refractive surgery, such as LASIK (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis). A history of such surgery is necessary information because periorbital surgery particularly canthopexies and levator surgery, can affect the refractive characteristics, cause mechanical irritation of the conjunctiva and cornea, or affect the corneal flap.28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree