CHAPTER 33 Blepharoplasty in the East Asian patient

*The figures in this chapter represent original artwork prepared by the author.

Introduction

A major problem here is that surgical “Westernization” really doesn’t work on an Asian face with an Asian skeleton. The outcome typically looks neither Western nor East Asian, and the one who opted for it ends up feeling alienated from both cultures. For this reason it is prudent to discourage loss of one’s ethnic integrity,1 especially doing blepharoplasty, where lid fold creation and placement, and medial epicanthoplasty maneuvers, are essentially irreversible.

Understand also that the aesthetics of Asian blepharoplasty encompass far more than the creation of lid folds on upper eyelids.2

The history of Asian periorbital surgery

• The first description of Asian upper lid surgery done solely for aesthetic purposes was in 1896, in Japan, by Dr. K. Mikamo.3 His technique involved three braided silk sutures, placed transdermally, grasping a small purchase of conjunctiva, and then exiting. The sutures were then ligated and left 2–6 days before removing.

• A more well-known early description of the suture technique was published in 1926 by Dr. Kozo Uchida,4 who reported on 1523 patients. He used three sutures of catgut, with knots buried beneath the skin.

• Three years later, in 1929, the first incisional technique was reported in Japan, also using catgut. This report appeared in the Japanese Journal of Clinical Ophthalmology, authored by Dr. M. Maruo.5 Many other operative descriptions appeared in Japanese journals between Dr. Maruo’s article and the first “known” English publications on the subject of Asian eyelid surgery.

• The increased Western presence in Japan and the Philippine Islands in the aftermath of the World War II, in Korea beginning in the 1950s, and in Southeast Asia thereafter, led to a misunderstanding – both by local surgeons and by Western surgeons – of the desires and intentions of those requesting Asian lid fold procedures. “Westernization” was somehow substituted for a subtle desire to enhance natural Asian beauty in a population that poorly understood the anatomical differences, and to what degree these differences were capable of impacting a person’s life. The lid configuration most desired was one that actually occurred naturally in many East Asian eyes – a small pretarsal segment with the crease running parallel to the lash line centrally and laterally but migrating progressively closer to the lid margin nasally. The smaller epicanthal canopies were also preferred.

• The goal distortion was aided by Dr. Ralph Millard’s report, which was the first one on Asian eyelid surgery that was widely distributed in the English language, “Oriental Peregrinations:” with a subsection entitled, “Oriental to Occidental.” It appeared in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in 1955.6 In this article Dr. Millard emphasized “Westernization” to a huge English speaking population, while the many earlier Asian surgeons, who also advocated “Westernization”, did so to a far more restricted audience.

• The other two early English essays on the subject were by Dr. Sayoc7 in 1954, who sutured the dermis of a pretarsal incision to the anterior aspect of the tarsus, and Dr. Fernandez from Hawaii in 1960, whose publication entitled, “The double eyelid operation in the Oriental in Hawaii”,8 became the world standard for open technique, and remains popular to this day. It was this operation that the senior author first learned, expanding it into his own more precise (“Flowers”) technique, which itself is widely used today.9 In 1993 the senior author worked closely with Dr. Fernandez, re-drawing his illustrations for anatomical clarity and more accurately describing his “landmark” operation, which then appeared in that year’s April issue of Clinics in Plastic Surgery (which Flowers himself edited).10

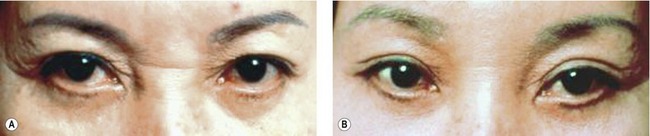

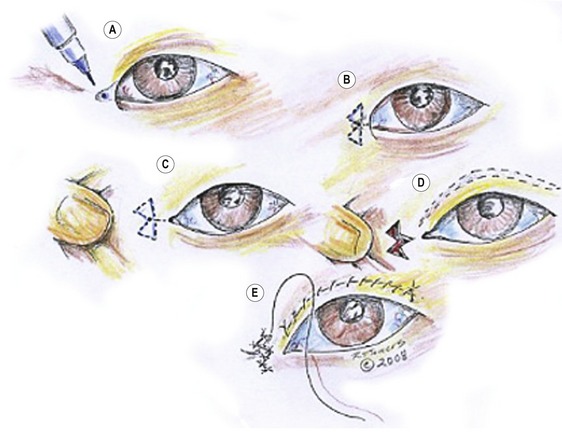

• Credit for the splendid split V-W medial epicanthoplasty (Fig. 33.1) belongs to Dr. Junichi Uchida.11 But his “W” scars were unnecessarily large, and he usually connected the upper limb of his lid fold incision with the upper aspect of the W, which rotated the nasal extension of the lid fold too far above the lid margin, “Westernizing” the eye unnecessarily and well beyond contours that occur naturally in Asians. This operation also encouraged deforming contractures with an incision encircling the medial canthus.

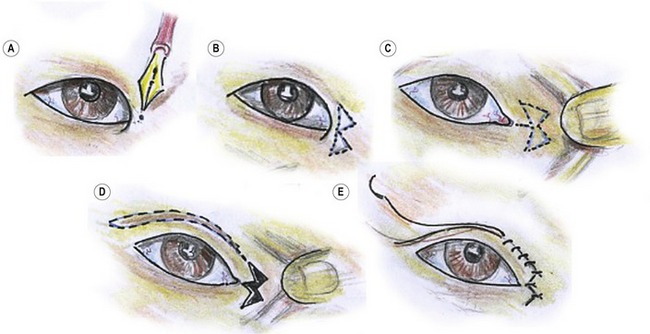

• The senior author (Flowers) modified and solved these problems by simply reducing the size of the W, keeping the upper limb of the W well above the medial extent of the lid fold, or lid fold incision, and suturing more meticulously12 (Figs 33.2, 33.3), emphasizing also the meticulous placement and removal of the tiny epicanthoplasty sutures – avoiding wound disruption and secondary healing.

Fig. 33.2 Flowers’ modification of Uchida medial epicanthoplasty. A, Mark the key point of the epicanthoplasty 0.5 mm lateral to the desired medial extension of the inner canthus. B, The marked point in A becomes the apex of the center of the W. C, Pull the skin nasally so the W excision can be marked – usually to include the little extra skin between the two triangles. Keep the W as small as is feasible. D, Excise the joined triangle, within the W and split skin (the V) right down to the epicanthus. E, Closure of the epicanthal incisions (see Fig. 33.3). The difference between this and the Uchida’s procedure is the small W and the fact that the medial extent of the crease incision always falls well beneath the superior limb of the W, for a more natural Asian look.

The split V-W medial epicanthoplasty is far superior, less deforming, and has much less scarring than the Mustardé “stick figure”(jumping man) or the many other Z-plasty modification epicanthoplasty.13 Lots of other techniques attempt to solve the prominent medial epicanthal canopy, but the authors found none with benefits that exceed those of the split V-W-plasty.

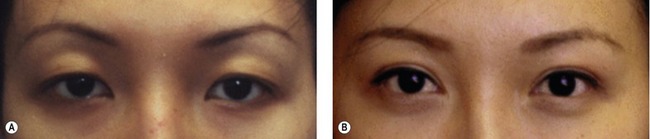

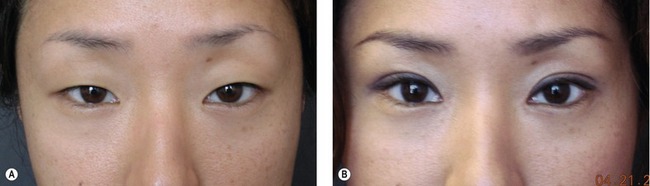

Creating a lid fold is not the most challenging aspect of Asian lid surgery. Symmetry, grace, accuracy and naturalness are far more important, and more difficult to achieve (Fig. 33.4). These aspects of Asian lid surgery were introduced, and stressed repeatedly over the last 35 years by Flowers.14,15 Minor adjustments were defined, clarified and refined.

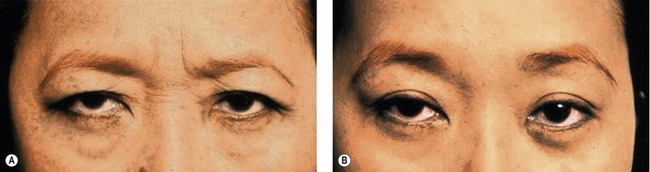

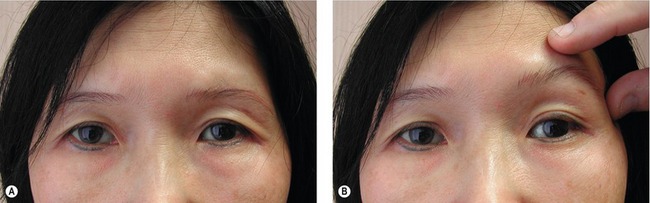

Flowers also pointed out the importance of combining frontal lift with lid fold procedures for most females over 30 years of age (Fig. 33.5), or simply substituting a brow elevation operation for lid surgery16 when precise lid folds exist, but are hidden by a droopy brow with overhanging lid tissue17 (Fig. 33.6).

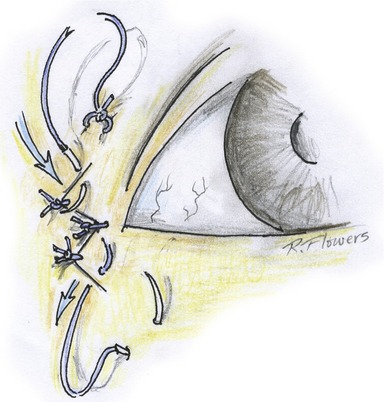

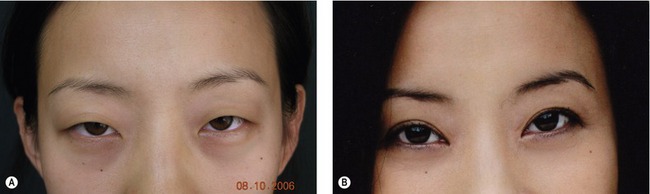

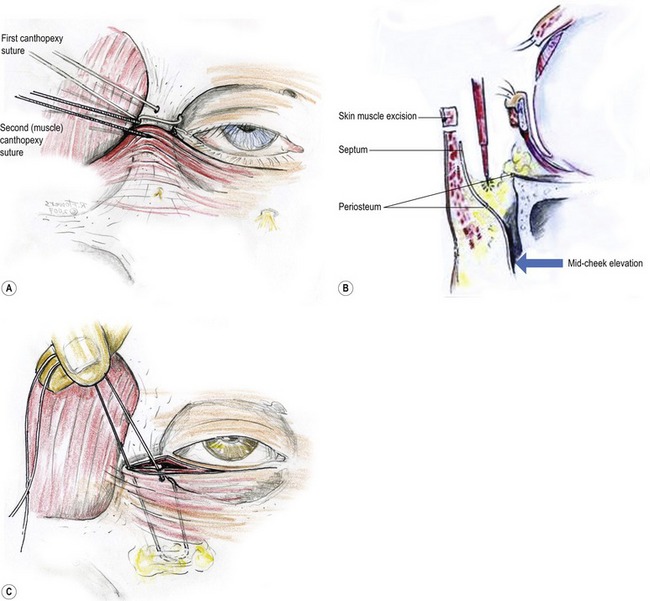

Also emphasized by the senior author in his many graduate courses on Asian lid surgery was the repair of lid ptosis simultaneous with lid fold creation. Precise measuring techniques and adjustments were developed to ensure symmetry of the pretarsal skin segments (most commonly caused by brow asymmetry) – plus the recognition of prominent globes on one, or both sides, and how to lend symmetry to repair in their presence. Flowers also stressed the importance of a new type of lower lid repair that eliminates scleral show and restores lower lid posture and tilt, both in primary and secondary eyelid procedures18 (Fig. 33.7). Fig. 33.7A shows the components of the two-layered canthopexy so effective in restoring youthfulness, and correcting the iatrogenic, developmental, and traumatic deformities.

Fig. 33.7 A, The two-layered canthopexy corrects the lower lid and retinacular laxity and atonicity. The first layer, the lateral canthal tendon and retinacular tissue are secured into a drilled hole in the orbital rim, exiting at its anterior medial aspect. The second layer of orbicularis muscle flap and other adherent tissues is sutured to the bone rather than pulled “into” the orbital rim. B, Note the release of arcus marginalis, and periosteum which allows the second layer of the canthopexy to include periosteum, orbital septum, fat, orbicularis, cheek fat, and skin. This second layer of the canthopexy serves as a magnificent midcheek lift, and often garners additional support from an absorbable suture, securing it to a drilled hole. C, Connecting the malar fibrofatty tissue and periosteum into a drill hole in the lower lateral orbital rim.

Anatomy and physical evaluation

Unique anatomical characteristics of East Asian eyelids

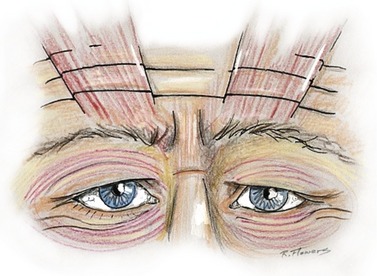

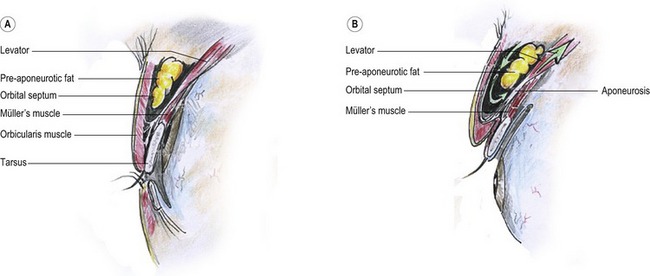

For years it was thought that supratarsal creases formed as a result of fibers from the aponeurosis continuing into the muscle or perhaps even into the dermis. Although commonly described, there is little evidence that they actually exist as proven entities. Lid creases consistently form precisely at the lowest point of the septo-aponeurotic sling’s descent into the lid.19 This sling is created by the (often delicate) fusion of the orbital septum with the aponeurosis (Fig. 33.8A), while the pre-aponeurosis fat is acting rather like a “ball bearing.”

Fig. 33.8 A, The septo-aponeurotic sling. The aponeurosis joins with the orbital septum at variable levels, creating a sling that contains the orbital fat. The level that this sling descends into the lid defines where the lid fold forms. B, When the levator muscle retracts, the sling rolls inward and upward, with the pre-aponeurosis fat acting rather like a “ball bearing”.

When the levator muscle retracts (Fig. 33.8B), the sling rolls inward and upward. The orbicularis is, without question, adherent to the orbital septum (with or without the theoretic “fibers”), and this causes the orbicularis to invaginate upon eye opening – with that same adherence as when the same septo-aponeurotic sling rolls inward and upward.

This characteristic makes it easy to discern East Asian from non-Asians in a simple sketch by simply placing the eyebrows high above the eyes (Fig. 33.9).

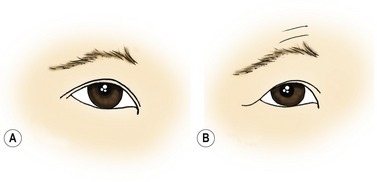

Double eye is the common term used in Asian communities for an upper eyelid showing a dominant crease in its lower aspect, along with it at least a little visible pre-tarsal (or sub-lid-fold) skin, if only in the lateral portion of the eyelid (Fig. 33.10). Not infrequently there will be a well-defined lid fold on one side, while minimal to no crease may be visible on the other.

It is not uncommon for even youthful East Asians, to have such precipitous drops in eyebrow position after upper lid excision and/or invagination (lid fold creation), that they require simultaneous (or deferred) forehead or brow lifts. The condition responsible for this is known as compensated brow ptosis,20 a term devised and popularized by the senior author. Compensated brow ptosis is the very common condition where the resting level of the eyebrows is so ptotic and low that it interferes with unobstructed forward vision, especially laterally, thereby forcing the frontalis muscles into constant contraction in order to see. Because the frontalis usually inserts mainly into the medial brow, the overhang that most needs correcting is usually lateral aspect. The medial brow overcorrects in its attempt to clear the lateral brow overhang. The frontalis muscles are forced to contract for 16–18 hours a day without relaxing.

Some patients with lid folds hidden beneath overhanging eyelid and brow skin require only frontal lifts to reclaim, or display for the first time, lovely natural lid creases, or “double eyelids” (Fig. 33.11). The “gift” is received without the swelling and other early postoperative morbidities seen with invasive lid invagination surgery (see also Fig. 33.26).

The desirability of lid folds (“double” eyes)

There is a preference in most Asian cultures for a distinct lid crease, residing one to four millimeters above the lash line, extending slightly beyond the lateral canthus (Fig. 33.12). Rarely ladies prefer it even higher. It replicates the pleasant curvature of the upper lid margin, and in so doing confers an illusion of a larger, longer eye. But the crease’s characteristics must resemble those that occur naturally in Asians, meaning it moves progressively closer to the lid margin along the medial third of the eyelid.

Over the millennia, Asian artists and sculptors have often chosen “double” eyelids to magnify beauty within the objects of their creativity. Even today millions of young and not so young Asians – all potential blepharoplasty patients – spend as much as an hour and a half each morning applying intricate combinations of transparent tape and heavy mascara in ways that force a lid crease to form. Sometimes skin glue or adhesive produces a similar effect, but this method carries with it a rather bizarre lagophthalmos on blinking. The technique persists only because the person hosting the phenomenon is blinded by the “blink” and doesn’t see the deformity.

Sometimes the slender-slit or pseudo-blepharoptotic eye carries with it such delicate grace and submissive beauty, creating such a magnificent work of art – that it begs to remain undisturbed. In other persons a similar lid may suggest a “sinister” aura, which can be extremely restrictive socially and professionally. There is an ancient Chinese adage suggesting that one should never trust a person with slender-slit narrow fissure type eyes. Generally such an Asian characteristics (Fig. 33.13) yield in desirability to the more “open” and “accessible” appearance of a naturally occurring, or skillfully created, “double” eye.

Natural and unnatural Asian lid folds

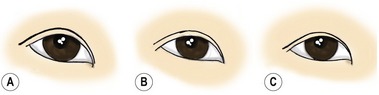

When lid folds occur naturally in East Asian eyelids, they have physical characteristics which differ from those occurring in other populations.21 In the youthful East Asian a natural fold typically parallels the lid margin in the outer two-thirds of the eyelid, closing towards the eyelid margin as it proceeds nasally. Medially, the crease may either end just above the epicanthal canopy (usually preferable) (Fig. 33.14A), extend to its medial margin (Fig. 33.14B), or dive beneath the epicanthal canopy (Fig. 33.14C). Sometimes, in Asians with prominent noses, and occasionally in those without, there may be no epicanthal canopy or epicanthus at all.

In Western and other non-Asian eyes the lid folds commonly parallel the lid margins all the way across the eyelid, but often move further away from the lid margins nasally, exposing more pretarsal skin. The latter rarely occur naturally on youthful East Asians, but sometimes the “crease”, especially when very close to the Asian lid margin, will parallel the lash line (Fig. 33.15A). The one situation where we see Asian lids with taller pre-tarsal segments nasally is after bad surgery or where there is a natural lid crease with a once fully visualized pretarsal component, but which is no longer exposed laterally (because of years of progressive scalp and forehead stretching). This causes an increased response activity in the frontalis muscle which usually inserts predominantly into the medial brow (Fig. 33.16).

Fig. 33.15 A, Another type of natural fold where a crease of very small height parallels the lid margin throughout its length. B, As the brow drops with age, the responding frontalis muscle raises the medial brow more in its quest to clear the lateral overhang. (See Fig. 33.16 for the typical origin of the frontalis muscle.)

In its attempt to raise lateral brow overhang, because of its medial brow insertion, it must overcorrect medially, and in so doing exposes a lot more pretarsal skin nasally than laterally (Fig. 33.15B). With overhang decreasing the visualized lateral pretarsal skin, an unnatural un-Asian appearance evolves, which also has an older appearance, in an area that could be a focus of attractiveness. Figure 33.17 shows a modest deformity of this type. Manual elevation of the left brow emphasizes how correction lies not in an eyelid operation (which would only worsen the condition), but with lateral brow position restoration, which cancels the muscle’s need to overcorrect, it frees the medial brow to drop into a more natural resting position.