Bicaval Liver Transplantation (with Venovenous Bypass)

Greg J. McKenna

DEFINITION

Bicaval liver transplant (caval interposition) is defined as the removal of a diseased liver along with its retrohepatic vena cava, and the replacement with a donor allograft in the orthotopic position, reconnecting the supra- and infrahepatic vena cava of the donor allograft to restore caval flow.

The bicaval liver transplant can be performed both with and without venovenous bypass.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history should be performed. In particular, the liver disease etiology should be determined, along with other symptoms and signs of liver disease including jaundice, asterixis, ascites, varices, and encephalopathy. This helps define the indication for liver transplantation. The history should also delineate any contraindications for liver transplantation. Any comorbid conditions such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, renal disease, and pulmonary diseases need to be identified. Additionally, any history of cancer or active infection needs to be clarified and cleared before transplantation can occur.

After defining a proper indication for transplantation and ensuring no contraindications exist, the natural history of a patient’s liver disease is compared to the expected survival after liver transplantation1 to determine if the procedure is warranted. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) is a prognostic score that uses three laboratory parameters to define the 3-month survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. The Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score is a useful prognostic tool that defines the relative risk of mortality in patients with cirrhosis based on clinical manifestations of the disease. Patients with a MELD score greater than or equal to 15 and a CTP score greater than or equal to 7 are suitable for liver transplantation, because they can be expected to have an improved survival after liver transplantation.2 With increasing scores from these models, a worse prognosis is expected, and the urgency for transplantation also increases.

Progression to decompensated cirrhosis is manifested clinically as ascites, variceal bleeding, encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS). The most serious findings are SBP and HRS, and candidates with SBP have a median survival of less than 1 year, and those with type 1 HRS have a median survival of 2 weeks.1,3,4

Social work clearance and/or psychiatry clearance is obtained to ensure that the candidate will have the necessary support network to handle the complexities and demands of a liver transplant and that they have the financial support to obtain the immunosuppression drugs needed.

Substance abuse and sobriety clearance are necessary in patients with Laënnec’s cirrhosis or history of substance abuse. Patients need to be free of alcohol for 6 months and in the case of Laënnec’s cirrhosis need to have completed a course of Alcoholics Anonymous or other suitable alcohol counseling.

Dental clearance needs to be obtained, and if necessary, teeth with caries should be removed.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Biochemistry—The necessary laboratory assessment for evaluation, including complete blood count, electrolytes, blood urea, creatinine, liver enzymes, international normalized ratio (INR), and albumin, are measured. Serologic tests include HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis A virus (HAV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and herpes simplex virus (HSV).

Cardiac—Electrocardiogram (ECG) is used to diagnose arrhythmias and to screen for any potential history of prior coronary artery disease.

Cardiac—Stress testing and/or dobutamine stress echocardiography screen for occult coronary disease and positive results needs verification with a left heart catheterization, because perioperative mortality is high in those with coronary artery disease.1 Doppler echocardiography is a good screening test for pulmonary hypertension and positive results need verification with a right heart catheterization measuring pressures.

Imaging—Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen including MR angiography can define the vasculature, the location of any transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) stents with respect to hepatic veins and portal vein, and the presence of any portal vein thrombus. Thrombosis of the portal vein can be removed or bypassed, but if the entire portal system including the superior mesenteric vein and splenic vein are occluded, there is a high risk of mortality and graft loss. The celiac axis is examined, ensuring there is no stenosis indicative of an arcuate ligament syndrome, because it is difficult to identify compromised arterial flow intraoperatively when the arcuate ligament is relaxed during the transplant.

Imaging—MRI of the abdomen identifies any hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and stages them to ensure the number and size meet the tumor criteria set out by the appropriate regulatory body. The MRI also identifies any contraindication to transplant such as gross vascular invasion of the portal vein, hepatic vein, or vena cava, or any extrahepatic spread of the HCC. The HCC locations must be noted when the vena cava is being cut to maximize cuff length during the hepatectomy and to ensure no oncologic compromise.

Imaging—Duplex ultrasound (DUS) is used as part of the screen for HCC every 6 months in cirrhotic patients (alternating with an MRI). In addition to identifying potential liver lesions, it can evaluate the gallbladder and biliary tree

and provide information on the flow and direction of blood through the portal vein, hepatic veins, and hepatic artery.

Renal—Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is measured with an iodothalamate clearance test or estimated with a calculated creatinine clearance based on laboratory values. The presence of pretransplant renal insufficiency is an important predictor of posttransplant renal failure and survival. Those patients with chronic kidney disease stage 4 or 5 (i.e., GFR <30 mL per minute), in addition to liver failure, should be considered for a combined liver-kidney transplant.1

Endoscopy—Esophagoduodenoscopy is done in all patients to assess for esophageal varices and look for gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies. Colonoscopy is performed as part of the oncologic screen in age-appropriate candidates and those with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). ERCP is performed in patients with PSC and cholangitis symptoms, as well as PSC and elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) tumor markers to rule out cholangiocarcinoma.

Pulmonary—Although not done routinely, based on history and clinical parameters, an arterial blood gas (ABG) and/or pulmonary function tests are performed. Any patient suspected of having hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) needs an ABG with the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) response to 100% oxygen administration measured. Any shunts from HPS can be screened with a Bubble echocardiogram and quantified with a macroaggregated albumin scan. Patients with severe hypoxia that does not correct and a shunt fraction greater than 20% are at high risk of postoperative mortality.1

Oncology—Age-appropriate screening is performed for candidates including mammograms.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

The surgeon must have knowledge of the recipient vasculature including the presence of any mesenteric vein thrombus, TIPS stent, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) history, and any Greenfield filters. The planning should also identify the location of any malignancy in relation to the hepatic veins and vena cava.

Consent of the recipient should include both operative risks (i.e., bleeding, infection, allograft failure, hepatic artery and biliary complications) and donor risks (i.e., infection and malignancy transmission).

Positioning and Draping

The recipient is supine with arms tucked along the sides. Insert a Foley catheter, nasogastric (NG) tube, and core temperature probe.

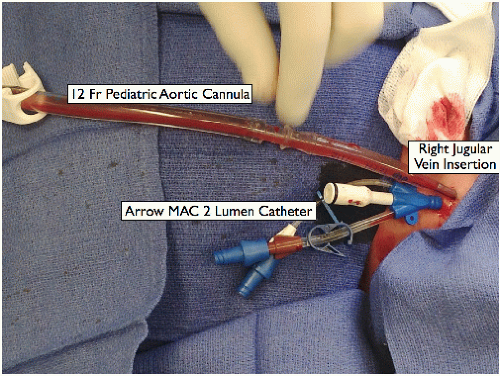

Place a 12-Fr pediatric aortic cannula for bypass. The anesthesiologist inserts it into the internal jugular vein using the Seldinger technique (FIG 1).

Pad all body parts that come in contact with the retractor arms. Wrap the legs with Ace compression bandages; sequential compression devices (SCDs) are not typically used. Firmly fix the patient in place to facilitate angulation of the bed during surgery.

Prepare the skin from the level above the nipple to the midthigh and laterally to the level of the table.

Drape the abdomen from below the nipples to the upper thighs. Place a towel over the groin. Expose both the left and right femoral triangles with the draping for the subsequent bypass cannula insertion.

TECHNIQUES

PLACEMENT OF INCISION

Make a right-sided subcostal incision with midline vertical extension (“hockey-stick” incision). For obese patients, a bilateral subcostal incision with midline extension (“Mercedes-type”) can be used, with the subcostal portion 5 cm below the costal margin.

RETRACTOR PLACEMENT

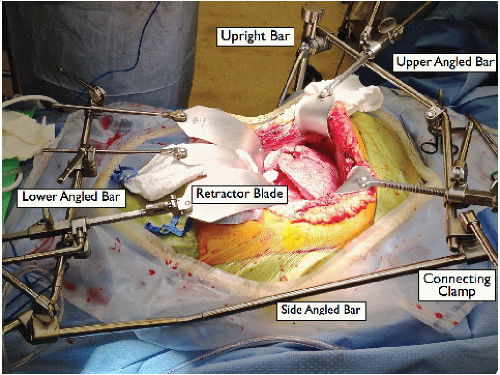

Place a Thompson retractor (FIG 2).

Upright bars × 2: a right side superior upright bar at the level of the shoulder and a left side inferior upright at the level of the hip

Crossbars × 3: an upper angled bar with three retractable clamps attached to the superior upright, a lower angled bar with two retractable clamps attached to the inferior upright, and a side-angled bar connecting the inferior upright to the upper cross bar at the left corner with a clamp

Blades: On the upper crossbar, two curved blades for retracting the abdominal wall/costal margin superior and laterally, and one finger blade attached to the retractable clamp to retract the liver. On the lower crossbar, two malleable blades attached to the retractable clamps to retract the intestines.

Place padding between any parts of the retractor bars that may come in contact with the recipient body, particularly at the right shoulder.

DIVISION OF THE FOUR HEPATIC LIGAMENTS

Divide the falciform ligament between 0 silk ligatures and continue with an electrocautery toward the interior surface of the hepatic veins.

Mobilize the left lobe of the liver by dividing the left triangular ligament with electrocautery (lifting the left lobe and placing a lap sponge to protect the spleen and stomach). Avoid the phrenic veins superiorly.

Divide the gastrohepatic ligament from the hilum to the diaphragm with electrocautery (or between 2-0 silk ligatures if collaterals are present). Any replaced left hepatic artery is tied and divided.

Detach omental adhesions to the gallbladder and mobilize the right lobe of the liver by dividing the right triangular ligament with electrocautery. Start at the inferior liver border of the liver by dividing the hepatorenal ligament and extend this plane of dissection around the lateral margin of the right lobe. Expose the right side of the inferior vena cava (IVC).

INSERTION OF THE FEMORAL VEIN BYPASS CANNULA

Bicaval liver transplant can be performed with or without venovenous bypass. The decision for venovenous bypass is usually made during preoperative planning for the case; however, it can be initiated intraoperatively if the patient becomes hypotensive during vena cava test clamping.

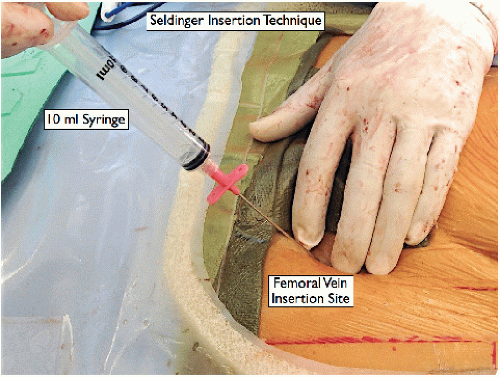

Landmark and palpate the femoral artery (the midpoint of the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic symphysis) (FIG 3). The femoral vein lies 1 cm medial and 1 cm caudal to the femoral artery.

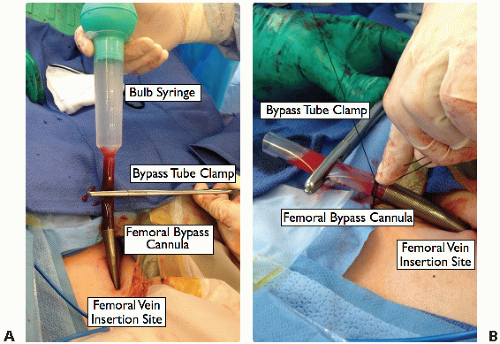

Insert the bypass cannula guidewire into the femoral vein via a Seldinger technique. Use a scalpel to make a 5-mm nick in the skin at the wire. Two successive dilators enlarge the orifice and insert the bypass cannula over the wire. Flush the cannula with saline from a bulb syringe, clamp it with tube clamps, and fix it to the skin and drapes with two 0 silk sutures (FIG 4A,B).

HILAR DISSECTION

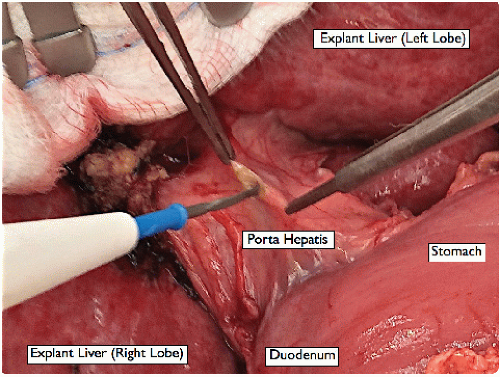

Retract the liver cephalad with the finger retractor attached to the superior bar of the Thompson retractor, exposing the hilum for dissection of the porta hepatis (FIG 5).

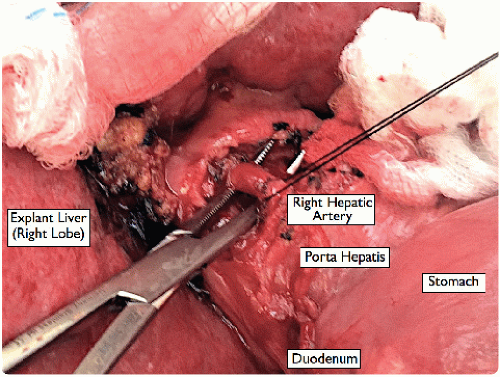

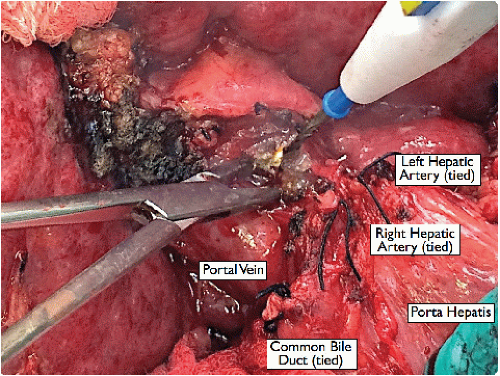

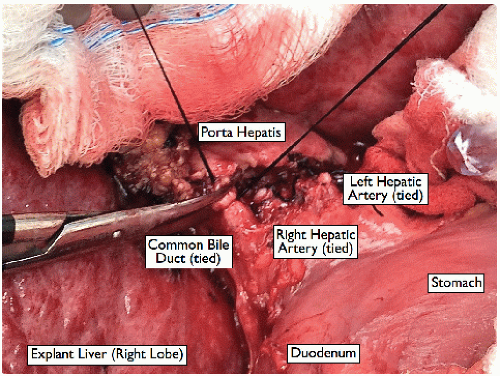

Dissect the left and right hepatic artery branches (and any other hepatic artery branches) from the surrounding tissues using a fine dissecting tonsil, and divide them between 2-0 silk ligatures near the liver (FIG 6).

If a replaced right hepatic artery is identified posterior to the bile duct, trace it high up into the liver before dividing.

Divide the cystic duct divided between 2-0 silk ligatures to facilitate a high division of the bile duct. Divide the recipient bile duct as high as possible, allowing a shorter donor bile duct to be used later for the anastomosis (FIG 7). Use a right angle to dissect around the bile duct, directing it away from the portal vein.

Lift and divide the peritoneal tissue overlying the portal vein with a dissecting tonsil, skeletonizing circumferentially around the portal vein toward the portal bifurcation (FIG 8).

FIG 7 • Ligation of the common bile duct. Leave ample length to facilitate a tension-free anastomosis during the liver transplant. |

INSERTION OF THE PORTAL VEIN BYPASS CANNULA

Skeletonize the peritoneal tissue on the portal vein cephalad with curved Mayo scissors with a stripping motion, exposing the portal bifurcation. Individually ligate the left and right portal branches with a 2-0 silk. Place a portal clamp (50-degree angled Castaneda clamp) on the proximal portal vein, and cut the distal vein high at the bifurcation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree