Benign Epithelial Tumors, Hamartomas, and Hyperplasias: Introduction

Benign epithelial tumors, hamartomas, and hyperplasias comprise a large and disparate group of tumors and no single classification system unifies them, as their cells of origin and clinical presentation can vary substantially. In this chapter, the clinical entities are grouped by clinical or histologic features to better present them from a practical diagnostic and treatment perspective (Table 118-1).

|

Seborrheic Keratosis

|

Epidemiology and Clinical Features

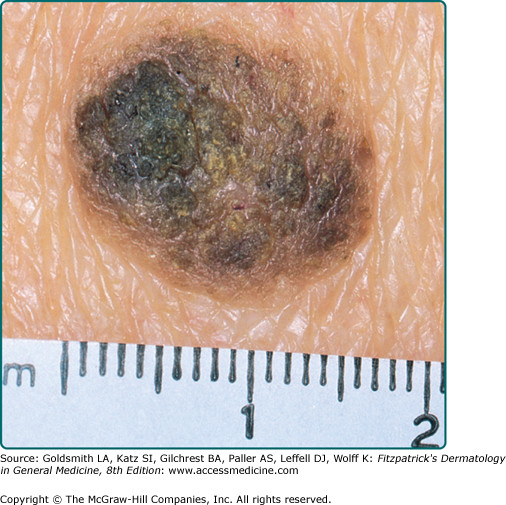

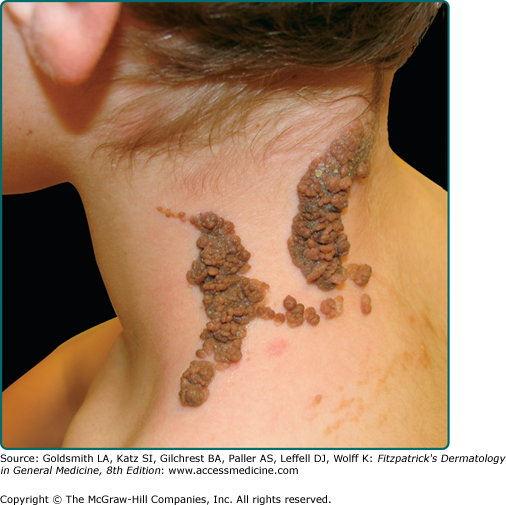

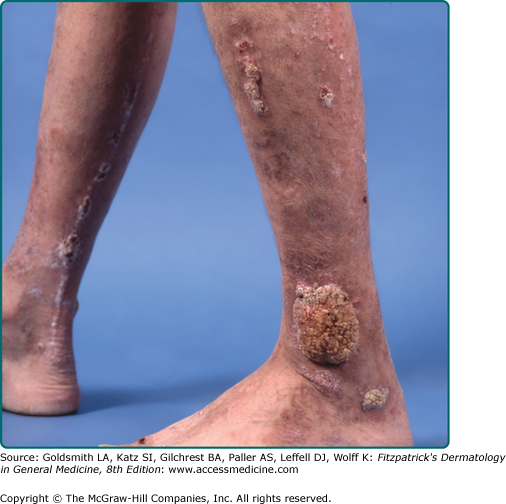

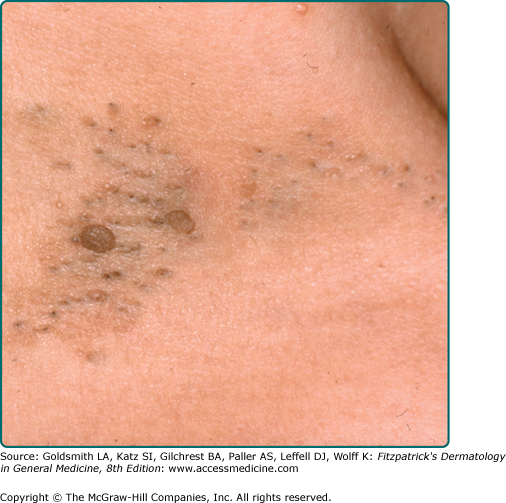

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin and a frequent focus of patient concern because of their variable appearance. These lesions are common in middle-aged individuals and can arise as early as adolescence.1 Although there are many clinical variants of the lesions, these lesions usually begin as well-circumscribed, dull, flat, tan, or brown patches. As they grow, they become more papular, taking on a waxy, verrucous, or stuck-on appearance (Figs. 118-1 and 118-2). Many lesions display distinctive pseudohorn cysts that likely represent plugged follicular orifices. SKs may arise on any nonmucosal surface, and multiple lesions may be distributed in a Christmas tree pattern along skin folds or in Blaschko’s lines.2 The color of these lesions ranges from pale white to black. At times, distinguishing these lesions from a nevus or melanoma can be clinically challenging. Because melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and other cutaneous malignancies have been reported to arise in SKs, care must be taken to critically evaluate rapidly growing, symptomatic, or unusual lesions.3,4

Etiology

The name seborrheic comes from the Greek word for sebum, and is a misnomer for these common growths. While the precise etiology of SKs is unknown, it is a tumor of keratinocytic origin. Genetics, sun exposure, and infection have all been implicated as possible factors. Many individuals with SKs have a positive family history for the condition. SKs demonstrate irregularities in the expression of the apoptosis markers p53 and Bcl-2, though no genetic locus or chromosomal imbalance has been detected to date.5,6 The higher prevalence of SKs on sun-exposed skin implies a possible causative role.7

Viral infection has also been considered a possible cause of SKs based on occasional clinical similarities to warts. Although no human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA was detected in a study of 40 genital SK biopsies, nongenital skin yielded different results. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated HPV DNA has been demonstrated in 42 of 55 (76%) nongenital SK biopsies compared to only 13 of 48 (27%) healthy controls (p < 0.005).8 These findings indicate the possible role of viral infection in the development of SKs in nongenital skin.

Although the etiology of SKs remains unknown, the monoclonal nature of these neoplasms has been established in 2001.9 By tracking polymorphisms in a human androgen receptor, researchers found that more than half of the 38 SKs sampled, regardless of subtype, were clonal in nature.9 The development of SKs has also been associated with circulating epidermal growth factors and melanocyte-derived growth factors in addition to the local increased expression of tumor necrosis factor-α and endothelin-converting enzyme.10 The latter two are associated with an increased expression of the keratinocyte melanogen, endothelin-1, resulting in hyperpigmentation within SKs.

Clinicopathologic Variants

There are many clinicopathologic variants of SKs, and while distinction is usually unnecessary, the commonplace nature of SKs makes these variants relevant.

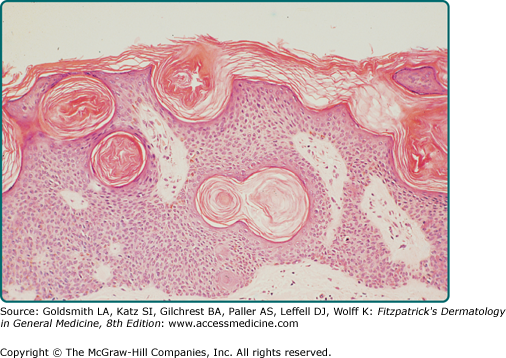

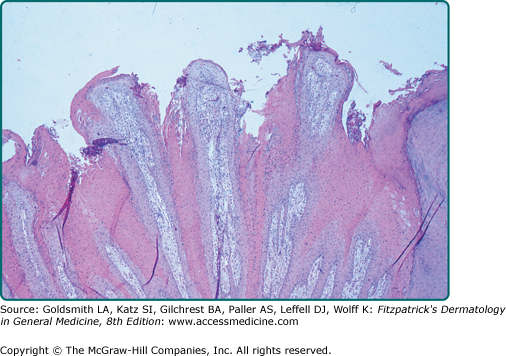

A common SK is classically described as a stuck-on, verrucous plaque (Figs. 118-1 and 118-2) with pseudohorn cysts (Fig. 118-3). Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis are hallmark pathologic findings. An increased number of melanocytes may also be present, giving lesions a tan or dark brown color. SKs are usually asymptomatic but may itch. Common SKs spare the palms, soles, and mucosa.

Reticulated SKs are also known as adenoid SKs. Some believe a solar lentigo usually precedes this often pigmented patch or papule. Histologically, there are small horn cysts suspended among interwoven strands of basophilic cells (Fig. 118-4).11

Stucco keratoses are also described as verrucous, serrated, hyperkeratotic, and digitate. These lesions are commonly 1- to 3-mm, flat-topped, white to tan papules that adhere tightly to the skin on the lower legs (eFig. 118-4.1). Histologically, no keratinocytic vacuolar changes or viral cytopathic changes are observed, thus distinguishing them from verruca plana.

Melanoacanthoma is also known as pigmented SK. This benign, slow-growing SK resembles melanoma clinically, and is often located on the trunk, head, or neck of older individuals. The term melanoacanthoma was introduced in 1960 to describe a pigmented lesion composed of nested melanocytes and keratinocytes.12

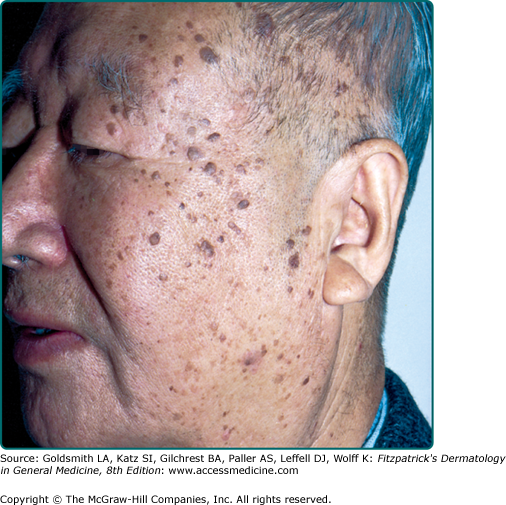

Dermatosis papulosa nigra are small dark brown to black papules that are commonly found on the face of individuals of Fitzpatrick skin phototype IV or greater. They are histologically identical to SKs (Fig. 118-5).

While often felt to be a distinct entity, some skin tags share clinical and histologic overlap with some SKs. These rough, 1- to 2-mm pedunculated papules are commonly located in areas of friction. The axilla, inframammary area, and neck are common locations where these papules commonly appear. Spontaneous regression can occur.

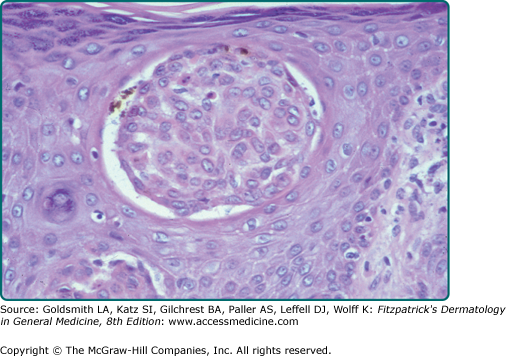

Clonal SK is a histologic term used to describe intraepithelial nests of basophilic keratinocytes of varying sizes with admixed melanocytes (Fig. 118-6). As previously stated, in one study, more than half of the 38 SKs sampled, regardless of subtype, were clonal in nature.9

Irritated SKs represent SKs that have been mechanically or chemically irritated or are involved in immunologic responses. Although inciting trauma is occasionally associated with irritated SKs, spontaneous inflammation is common (Fig. 118-7). Histologically, the dermis underlying these lesions is filled with a dense inflammatory infiltrate predominantly of lymphocytes. This inflammation is occasionally lichenoid or neutrophil rich. Swirled collections of eosinophilic keratinocytes can be seen in the epidermis.13 Eczematous changes in or around the lesion, also known as Meyerson phenomenon, can also be seen.14

Varying degrees of squamous atypia can be seen in SKs. Bowenoid transformation of benign SKs into squamous cell carcinoma in situ has been documented but the development of basal or squamous cell carcinoma in a SK is rare.15 Lesions demonstrating the histology of both SKs and malignancies have been reported.16,17 Although it is likely that most of these lesions represent collision tumors, malignant transformation of SKs into basal cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and melanomas can occur. In a retrospective study of 813 lesions histologically diagnosed as SKs, 5.3% were associated with nonmelanoma skin cancer. In this study, the most common malignancy was squamous cell carcinoma in situ, followed by basal cell carcinomas and invasive squamous cell carcinomas; no melanomas were observed.17 Clinically atypical or rapidly growing SKs should be biopsied to rule out the possibility of malignancy.

In the context of internal malignancy, individuals can develop multiple, eruptive SKs also known as the Leser–Trélat sign. Adenocarcinoma of the stomach is the most commonly associated malignancy,18,19 though adenocarcinoma of the lung and colon have also been linked. Other diseases reported to occur with eruptive SKs are leukemia, lymphoma, lepromatous leprosy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, erythrodermic eczema, and melanoma.20–23 Inflammation of eruptive SKs during chemotherapy, especially cytarabine, is known to occur (Fig. 118-7).24 The presentation of eruptive SKs with acanthosis nigricans led many to speculate a common reactive mechanism.25 Abnormal immune responses may also play a role in the development of this clinical sign.

Rapid growth, atypical morphologic features, unusual lesion location, or symptoms should all be considered when evaluating SKs, and care should be taken not to destroy a lesion that begs further pathologic examination. For any lesion with a possibility of malignancy, removal must be performed in a fashion that yields tissue for evaluation.

For clearly benign, yet symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable lesions, destruction with cryotherapy, electrodesiccation followed by curettage, curettage followed by desiccation, or laser ablation have all been shown to be effective. Reports of giant SKs measuring many centimeters have been treated successfully with either dermabrasion or topical fluorouracil.26,27 Surgical excision is also an accepted treatment approach, especially if the lesion is pedunculated and can be transected at its base. Common complications of these destructive measures include scarring, pigmentary alteration, incomplete removal, or recurrence. Recurrence of the lesions may occur, and it is not uncommon to require multiple treatments to ensure the complete destruction of the initial lesion. It is preferable to ensure that the method of removal minimizes the risk of scarring.

Epidermal Nevus

|

Epidermal nevus is a generalized term for hamartomatous proliferations of epithelium. The subtypes of this tumor differ according to the distribution of the lesions or the predominant histologic cell type: keratinocyte (verrucous epidermal nevus), sebaceous gland (nevus sebaceous), pilosebaceous unit (nevus comedonicus), eccrine gland (eccrine nevus), or apocrine gland (apocrine nevus). eTable 118-1.1 provides a classification of one framework to discuss this large and diverse entity. Currently, there are six different epidermal nevus syndromes described: (1) Proteus, (2) congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defect syndrome, (3) phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica, (4) sebaceous nevus, (5) Becker’s nevus, and (6) nevus comedonicus.28

Epidermal Nevus Variant | Predominant Structure | Morphology | Extent |

|---|---|---|---|

Verrucous epidermal nevus Localized Systematized Nevus unius lateris Ichthyosis hystrix Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus | Surface epidermis | Verrucous

Inflamed

|

Localized Widespread Widespread unilateral Widespread bilateral Localized |

Nevus sebaceous | Sebaceous glands | Yellow verrucous | Localized, rarely diffuse |

Nevus comedonicus | Hair follicles | Grouped comedones | Localized, rarely diffuse |

Eccrine nevus | Eccrine sweat glands | Nondescript papule | Localized |

Apocrine nevus | Apocrine sweat glands | Nondescript papule | Localized |

Becker’s nevus | Surface epidermis Hair follicles, + smooth muscles, melanization | Pigmented, hairy | Localized |

White sponge nevus | Mucosal epithelium | Gray-white plaque | Localized or diffuse |

Epidermal nevi occur in 1 in 1,000 live births.29 Eighty percent of lesions appear within the first year of life, with the majority of lesions appearing by age 14 years. There are rare reports of adult onset of epidermal nevi, with the oldest patient being a 60-year-old woman.30 Such late-developing epidermal nevi probably represent lesions that have always been present subclinically, but recent growth resulted in clinical recognition.31 There is an equal male–female prevalence, and most cases are sporadic. However, some familial cases have been documented.32

Verrucous epidermal nevus is also known as linear verrucous epidermal nevus or linear epidermal nevus.

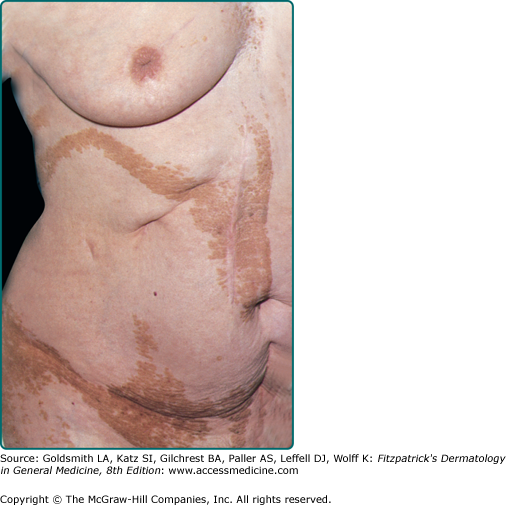

Verrucous epidermal nevi are characterized by localized or diffuse, closely set, skin-colored, brown, or gray–brown verrucous papules, which may coalesce to form well-demarcated papillomatous plaques (Fig. 118-8). Linear configurations are common on the limbs as is distribution in Blaschko’s lines or in relaxed skin tension lines (Fig. 118-9).

Extensive distribution of a verrucous epidermal nevus is termed systemized epidermal nevus. Variants of this type of nevus include nevus unius lateris (Fig. 118-10), epidermal nevi distributed on one-half of the body; and ichthyosis hystrix, epidermal nevi distributed bilaterally. Commonly, systematized nevi take on a transverse configuration on the trunk and linear configuration on the limbs.

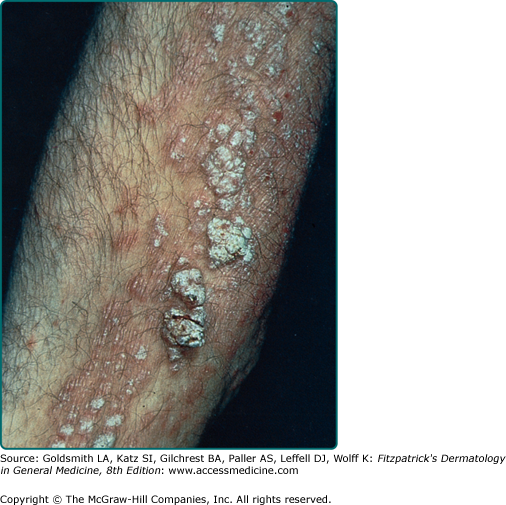

An epidermal nevus presenting with pruritus, erythema, and scaling is likely a variant of the epidermal nevus termed an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) (Fig. 118-11). These lesions are found most commonly on the buttocks and lower extremities.

Linear epidermal nevi tend to appear between birth and adolescence. Although congenital lesions tend not to expand significantly, lesions that present after birth may expand during childhood, stabilizing in size at or around puberty.33 Although intertriginous lesions may become macerated and secondarily infected, the majority of epidermal nevi remain quiescent after adolescence. Rare cases of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma arising within epidermal nevi have been reported. This malignant transformation is most common in middle-aged or elderly individuals, though the youngest reported case occurred in a 17-year-old woman.34

Epidermal nevi may present in conjunction with other epidermal lesions such as café-au-lait macules, congenital hypopigmented macules, and congenital nevocellular nevi and may be associated with abnormalities in other systems.33 (See Section “Epidermal Nevus Syndrome”).

Rarely, patients with epidermal nevi have offspring with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK), a condition resulting from a mutation in keratin 10 (K10). Paller et al35 investigated three families with this occurrence. The analysis of skin samples of parents and offspring with EHK demonstrated a parental mutation in one of the two K10 alleles within the epidermal nevus; nonlesional skin showed no mutation. Offspring showed the same K10 mutation as their parents.35 The presence of two genetically distinct cell lines in the parents, also known as mosaicism, is a result of postzygotic mutation during embryogenesis.36 If histopathologic evaluation of an epidermal nevus reveals findings consistent with EHK, the patient is at risk of having a child with EHK. Prenatal counseling may be very important for these patients.

There are ten histologic variants of the epidermal nevus, with over 60% of lesions displaying acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis (Fig. 118-12).37 Rare variants may have features similar to SKs, with thin, elongated rete ridges; or EHK, with compact orthokeratosis, vacuolization of the granular layer of the epidermis, and large keratohyalin granules within or outside cells.38 Epidermal hyperkeratosis may be a more common finding in ichthyosis hystrix. ILVEN is a histologically distinct variant of the epidermal nevus that displays a chronic dermal inflammatory infiltrate, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, and alternating bands of ortho- and parakeratosis. In this variant, the granular layer is absent underlying the areas of parakeratosis.39

(See Box 118-1).

Lichen striatus, linear Darier disease, linear porokeratosis, linear lichen planus, linear psoriasis, and the verrucous stage of incontinentia pigmenti may all have similar clinical presentations as the linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Lichen striatus may mimic ILVEN clinically, but is self-limited as compared with epidermal nevi. Histology may be useful in differentiating these entities. Linear Darier disease and linear porokeratosis can be differentiated pathologically with linear Darier disease having the distinct pathologic findings of acantholytic dyskeratosis, and linear porokeratosis having coronoid lamellae. Although some consider linear lichen planus and linear psoriasis to be variants of the ILVEN, the genetics and the immunology has yet to be fully characterized.40–42 Incontinentia pigmenti can be distinguished clinically based on the transient nature of this phase and the preceding verrucous phase. Histologically, this entity can be distinguished by its dyskeratosis, pigment incontinence, eosinophilic exocytosis, and basal layer vacuolization.

Complete excision of an epidermal nevus to the level of the deep dermis is necessary to prevent recurrences. However, based on the size and distribution of the lesion, excision may not be an appropriate treatment option. Multiple other surgical and medical treatments are available to treat or destroy these lesions. Laser ablation, electrofulguration, cryotherapy, and medium to full-depth chemical peels may offer partial or full destruction of lesions. Although topical retinoids and calcipotriene offer little relief, these medications can be used as an adjunctive therapy to increase the efficacy of the surgical intervention. Systemic retinoids and antipsoriatic agents may offer some clinical improvement. There are reports of successful treatment of ILVEN with etanercept.43 If malignant transformation is confirmed within an epidermal nevus, the lesion should be completely excised.

|

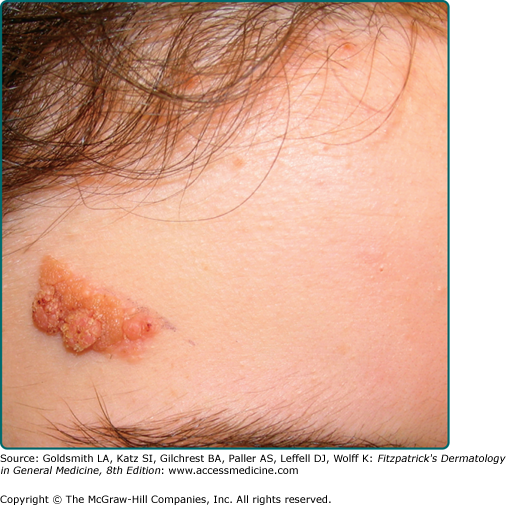

Nevus sebaceous is also known as nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn and organoid nevus.

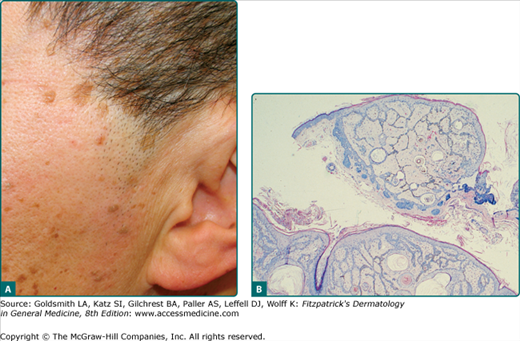

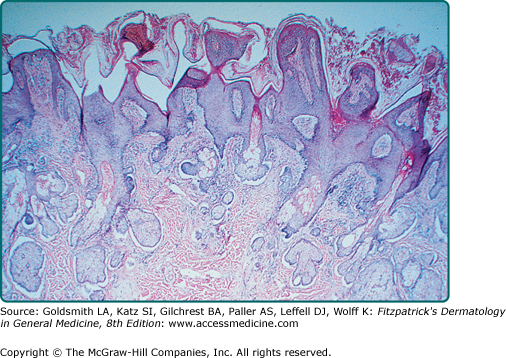

Nevus sebaceous presents as a linear, hairless, yellow, waxy, and verrucous plaque (Fig. 118-13). It can be flat at birth, becoming plaque-like under the hormonal influences of puberty. These nevi are common in the scalp, but there are reports of lesions on the face, chest, and in oral mucosa. Tumors can arise within nevus sebaceous. The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma.44 Other benign tumors reported to arise in a nevus sebaceous are the leiomyoma, syringoma, spiradenoma, hidradenoma, and keratoacanthoma.45 It was once believed that individuals with this tumor were at increased risk of basal cell carcinomas, but a retrospective review of 596 cases by Cribier et al revealed that most lesions initially diagnosed as basal cell carcinoma were actually trichoblastomas.46 A second retrospective study of 757 tumors confirmed this finding.47 This does not exclude the possibility of the development of basal cell carcinoma in these lesions. Rarely, malignant tumors such as apocrine carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant eccrine poromas may arise within nevus sebaceous.48

Nevus sebaceous syndrome is the very rare association of an extensive, congenital nevus sebaceous with ocular abnormalities and cerebral defects such as mental retardation or seizures. This syndrome is also known as Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome or organoid-nevus syndrome.49,50

Immature sebaceous glands located high in the dermis and malformed pilosebaceous units are features of nevus sebaceous (Fig. 118-14). Vellus hairs are more common than terminal hairs in these lesions. Epidermal acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can also be seen.

Epidermal nevi and aplasia cutis may be clinically similar to nevus sebaceous but biopsy can easily distinguish between these entities.

Excision of nevus sebaceous was common when these lesions were thought to carry an increased risk of basal cell carcinoma. Rapidly growing papules or nodules demand pathologic evaluation to evaluate for rare malignancies, but excision should be considered on a case-by-case manner.48

|

Nevus comedonicus is also known as comedo nevus, nevus follicularis keratosis, nevus acneiformis unilateralis, and nevus zoniforme.51 Nevus comedonicus is a rare hamartoma of the pilosebaceous unit.52,53 Clinically, comedo-like dilated pores with keratinaceous plugs present in a linear, nevoid, bilateral, or zosteriform pattern (Fig. 118-15).52 An inflammatory variant also exists, with suppurative cysts and acne-like lesions. These lesions appear on the face, chest, or upper arms at birth or during childhood.28 Nevus comedonicus syndrome is the association of nevus comedonicus with noncutaneous findings such as skeletal defects, cerebral abnormalities, and cataracts.54

Nevus comedonicus lesions follow a noninflammatory or inflammatory course and do not resolve spontaneously. The inflammatory course may result in scarring. Nevus comedonicus syndrome results in developmental, cerebral, skeletal, or ocular defects that present by the age 15 years.55

The hallmark findings in nevus comedonicus are keratin-filled epidermal invaginations associated with atrophic sebaceous glands or follicles. EHK may be seen.56

The differential diagnosis of this lesion includes acne vulgaris, milia, acne neonatorum, nevus sebaceous, and linear Darier disease.

The noninflammatory variant of nevus comedonicus is usually asymptomatic, with treatment based on the cosmetic concerns of the patient. The inflammatory variant can result in significant suppuration and pain, requiring medical or surgical intervention. Inflammation may be controlled with tazarotene cream or other retinoids, tacrolimus ointment, calcipotriene cream, and intralesional steroids.57 Keratolytics may be of some help. Systemic antibiotics may help to control infection or inflammation. Surgical interventions, such as extraction, excision, dermabrasion, or laser resurfacing, may result in good clinical results.58,59

An eccrine nevus, the simplest form of eccrine hamartoma, is characterized by an increase in the number or size of eccrine coils.60–63 Fewer than 20 cases of eccrine nevi have been described in the literature. Distributed on the trunk, arms, or legs, these lesions occur equally in men and women. Although there seems to be a childhood predominance, the onset ranges from birth to the eighth decade.64 The morphology of eccrine nevi may vary, appearing clinically as tan papules or normal skin.65–66 These lesions do not always display hyperhidrosis, however, when they do, treatment is targeted at the control of that symptom. Agents such as aluminum chloride solution, anticholinergics, antidepressants with anticholinergic activity, botulinum toxin, iontophoresis, or sympathectomy have been reported to help control the hyperhidrosis. Surgical excision of the lesion is also an acceptable treatment.67,68

Apocrine nevi are hamartomatous proliferations of mature apocrine glands often found within a nevus sebaceous. Clinical presentation varies, but they can be found as soft nodules or papules in the axilla or on the upper chest. Histologically, the apocrine glands extend from the epidermis to the fat. These lesions can be surgically excised if desired.69

|

Epidermal nevus syndrome is also known as Schimmelpenning syndrome, Feuerstein–Mims syndrome, and Solomon syndrome. Epidermal nevus syndrome is the association of any type of epidermal nevus with various cutaneous, ocular, neurologic, skeletal, cardiovascular, or urogenital developmental abnormalities. Historically, there have been six epidermal nevus syndromes described: (1) Proteus syndrome, (2) congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defects, (3) phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica, (4) sebaceous nevus, (5) Becker’s nevus, and (6) nevus comedonicus. Some authors argue that epidermal nevus syndrome is a collection of many different distinct clinical syndromes.

Happle70 proposed that the epidermal nevus syndrome is not a single entity but consists of at least six distinct diseases that differ in genetic origin and share the common feature of mosaicism. The entities include Schimmelpenning syndrome; nevus comedonicus syndrome; pigmented hairy epidermal nevus syndrome; Proteus syndrome; congenital hemidysplasia, ichthyosiform dermatitis, and limb defects syndrome; and phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica.

Epidermal nevus syndrome affects men and women equally and presents within the first 40 years of life. Inheritance is sporadic, although anecdotal reports of familial transmission have been reported.70 Although the exact incidence of epidermal nevus syndrome is unknown, a study of 119 cases of epidermal nevi showed that 33% of patients showed one or more extracutaneous abnormalities, 16% showed two or more abnormalities, 10% showed three or more abnormalities, and 5% showed five or more abnormalities.

Solomon and Esterly provided a detailed account of the spectrum of epidermal nevi seen in the epidermal nevus syndrome.29 They described seven types of lesions. The majority of patients had nevus unius lateris; 20% of patients had ichthyosis hystrix; and another 20% had what the authors termed the acanthotic form of epidermal nevus. These lesions presented as large, unilateral, brown, slightly scaly patches. About 10% of patients had linear nevus sebaceous involving the scalp and face. Localized linear verrucous nevus and a velvety epidermal nevus in the axilla similar to acanthosis nigricans were seen in a minority of cases. Some patients had a mixture of several types of lesions.

Table 118-2 lists the mucocutaneous changes other than epidermal nevus that may be seen in patients with epidermal nevus syndrome.71 Hemangiomas and pigmentary changes are found in 10%–20% of patients. Less common findings are hair abnormalities, dental abnormalities in association with mucosal epidermal nevi, and dermatomegaly. This last condition involves an increase in skin thickness, warmth, and hairiness. As discussed earlier, various cutaneous tumors may develop within the epidermal nevus.

|

A wide range of skeletal abnormalities has been reported (eTable 118-2.1).70–72 The incidence of skeletal changes has ranged from 15% to 70%.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree