Basal Cell Carcinoma: Introduction

|

BCC Epidemiology

BCC is the most common cancer in humans. It is estimated that over 1 million new cases occur each year in the United States. The malignancy accounts for approximately 75% of all nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) and almost 25% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States.1 Epidemiological data indicate that the overall incidence is increasing worldwide significantly by 3%–10% per year.2

BCC is more common in elderly individuals but is becoming increasingly frequent in people younger than 50 years of age. Christenson et al noted a disproportionate increase in BCC in women under age 40.3 Men are affected slightly more often than are women. Levi et al reported that the incidence of BCC rose steadily in the Swiss Canton of Vaud between 1976 and 1998 to levels of 75.1 in 100,000 in males and 66.1 in 100,000 in females.4,5 Stang et al in Westphalia, Germany found that the incidence rate of BCC during a 5-year period (1998–2003) was 63.6 in men and 54.0 in women.6 A study of NMSC in Aruba supported these findings.7 In that study, BCC was the most common type of skin cancer diagnosed between 1980 and 1995. Tumors were more frequent in patients older than 60 years of age, and 57% were in men. The highest percentage of lesions occurred on the nose (20.9%), followed by other sites on the face (17.7%).7 Incidence in Europe was examined by the recent study in Croatia. From 2003 to 2005, the crude incidence rate for the Croatian population of 100,000 was 54.9 for men and 53.9 for women. The vast majority of BCCs were located on the head and neck.8

BCC character develops on sun-exposed skin of lighter skinned individuals. Incidence rates of BCC in Asians living in Singapore increased from 1968 to 2006, especially among the older, more fairly complected Chinese patents. Skin cancer trends in Asians from 1968–2006 showed BCC rates increased the most among persons older than 60 years.9

BCC is rare in dark skin because of the inherent photoprotection of melanin and melanosomal dispersion. An estimated 1.8% of BCCs occur in blacks, and BCC is approximately 19 times more common in whites than blacks.10

Risk factors for BCC have been well characterized and include ultraviolet light (UVL) exposure, light hair and eye color, northern European ancestry, and inability to tan.1 An Italian study indicated the important role of sunburns, and therefore intense sun exposure, rather than that of prolonged sun exposure to increase the risk of BCC.11

BCC Etiology and Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of BCC involves exposure to UVL, particularly the ultraviolet B spectrum (290–320 nm) that induces mutations in tumor suppressor genes.12,13 UVB radiation damages DNA and affects the immune system resulting in a progressive genetic alterations and neoplasms. UV-induced mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene have been found in about 50% of BCC cases.14

Currently, it is thought that the upregulation of the mammalian development signaling pathway, Hedgehog (HH), is the pivotal abnormality in all BCCs, and there is evidence that little more than this upregulation is required for BCC carcinogenesis.15,16 The mutations that activate the aberrant HH signaling pathway are found in PTCH1 and Smoothened (SMO). Approximately 90% of sporadic BCCs have identifiable mutations in at least one allele of PTCH1, and an additional 10% have activating mutations in the downstream SMO protein.17 The most frequently identified mutations in PTCH1 and SMO are of a type consistent with UV-induced damage.18–20

The contribution of high-intensity sunlight exposure to BCC development in the general population is well established.11 A latency period of 20–50 years is typical between the time of UV damage and the clinical onset of BCC. Therefore, in most cases, BCC develops on sun-exposed skin in elderly people, most commonly in the area of head and neck.21

Some studies indicate that intermittent brief holiday exposures may place patients at higher risk than occupational exposure.9,22 An Italian study confirmed the role of intermittent sun exposure as a strong risk factor for BCC.11 Ramani and Bennett reported a significantly higher incidence of BCCs in World War II servicemen stationed in the Pacific theater than in those stationed in Europe. This suggests that several months or years of intense exposure to UVL may have deleterious long-term effects.23 Truncal BCCs can result from acute intense exposures sufficient to cause sunburn on the skin of the trunk among people whose ability to tan makes the skin of their face generally less susceptible to the carcinogenic effects of UV radiation.24

Other factors that appear to be involved in the pathogenesis include mutations in regulatory genes,17,25 exposure to ionizing radiation,26,27 and alterations in immunosurveillance.28–30

The propensity to develop multiple BCCs may be inherited. Included among heritable conditions predisposing to the development of this epithelial cancer are nevoid basal call carcinoma syndrome or basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS),31 Bazex syndrome,32 and Rombo syndrome.33 Patients with BCNS may develop hundreds of BCCs and may exhibit a broad nasal root, borderline intelligence, jaw cysts, palmar pits, and multiple skeletal abnormalities. BCNS occurs due to mutations in the tumor suppressor PTCH gene.34,35

Bazex syndrome is transmitted in an X-linked dominant fashion.32 Patients have multiple BCCs, follicular atrophoderma, dilated follicular ostia with ice pick scars, hypotrichosis, and hypohidrosis. In contrast, Rombo syndrome is transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion.33 Patients have vermiculate atrophoderma, milia, hypertrichosis, trichoepitheliomas, BCCs, and peripheral vasodilation. Hypohidrosis is not a feature of Rombo syndrome.

The role of the immune system in the pathogenesis of skin cancer is not completely understood. Immunosuppressed patients with lymphoma or leukemia36,37 and patients who have received an organ transplant have a marked increase in the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma but only a slight increase in the incidence of BCC.28–30,38 Bastiaens et al found that transplant recipients developed more BCCs on the trunk and arms than did nonimmunosuppressed patients.39 Harwood et al found that fewer BCCs occurred on the head and neck of renal transplant recipients, while more BCCs were found on the trunk and arms compared to the immune competent patients.38 Patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection develop BCCs at the same rate as immunocompetent individuals, based on similar risk factors.19,40,41 Immunosuppressed long-term alcoholics tend to develop infiltrative BCCs with increased frequency.20,42 A potential link between UVL and decreased immunity has been suggested by Gutierrez-Steil et al, who demonstrated that UVL-induced BCCs express Fas ligand (CD95L).43 They further showed that these cells were associated with CD95-bearing T cells undergoing apoptosis.43,44 This represents a potential mechanism by which UVL might help tumor cells avoid being killed by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Kaporis et al showed that immune suppressive regulatory T cells are surround BCC tumor nests thus providing another potential mechanism for BCC to evade host antitumor immunity.45

Clinical Manifestations

The presence of any friable, nonhealing lesion should raise the suspicion of skin cancer. Frequently, BCC is diagnosed in patients who state that the lesion bled briefly then healed completely, only to recur. BCC usually develops on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck but can occur anywhere on the body. Features include translucency, ulceration, telangiectasias, and the presence of a rolled border. Characteristics may vary for different clinical subtypes, which include nodular, superficial, morphea-form, and pigmented BCCs and fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FEP). The anatomic location of BCC may favor the development of a particular subtype.46

Nodular BCC is the most common clinical subtype of BCC (Fig. 115-1).47,48 It occurs most commonly on the sun-exposed areas of the head and neck and appears as a translucent papule or nodule depending on duration. There are usually telangiectasias and often a rolled border. Larger lesions with central necrosis are referred to by the historical term rodent ulcer (Fig. 115-2). The differential diagnosis of nodular BCC includes traumatized dermal nevus and amelanotic melanoma.

Pigmented BCC is a subtype of nodular BCC that exhibits increased melanization. Pigmented BCC appears as a hyperpigmented, translucent papule, which may also be eroded (eFig. 115-2.1). The differential diagnosis includes nodular melanoma.

Superficial BCC occurs most commonly on the trunk and appears as an erythematous patch (often well demarcated) that resembles eczema (Fig. 115-3).47 An isolated patch of “eczema” that does not respond to treatment should raise suspicion for superficial BCC.

Morpheaform BCC is an aggressive growth variant of BCC with a distinct clinical and histologic appearance. Lesions of morpheaform BCC may have an ivory-white appearance and may resemble a scar or a small lesion of morphea (eFig. 115-3.1). Thus, the appearance of scar tissue in the absence of trauma or previous surgical procedure or the appearance of atypical-appearing scar tissue at the site of a previously treated skin lesion should alert the clinician to the possibility of morpheaform BCC and the need for biopsy.

FEP classically presents as a pink papule, usually on the lower back.25,50 It may be difficult to distinguish from an acrochordon or skin tag. Similar to basal cell carcinomas, fibroepitheliomas of Pinkus express androgen receptors, supporting its classification as a basal cell carcinoma.51 The differential diagnoses of FEP includes acrochordon.52

Biologic Behavior

The greatest danger of BCC results from local invasion (Fig. 115-4). In general, BCC is a slow-growing tumor that invades locally rather than metastasizes.26,27,53,54 The doubling time is estimated to be between 6 months and 1 year. If left untreated, the tumor will progress to invade subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and even bone. Anatomic fusion planes appear to provide a low-resistance path for tumor progression. Tumors along the nasofacial or retroauricular sulcus may be extensive. Metastases are rare and most are said to more closely correlate to the size and depth of tumor invasion and less so to the histologic subtype of the original tumor.1

Although metastases are rare, significant patient morbidity, such as local tissue destruction and disfigurement can occur. In one informative case, a patient documented the progression of his own tumor with photographs over a 27-year period.28,55 The lesion, which encompassed an entire side of the face, including the maxillary sinus, apparently doubled over a 10-year period and grew rapidly in the 2 years before hospital admission. This scenario occurs in the context of physical or psychiatric disability that interferes with judgment or access to health care. In one of the first reports of giant BCC in India, a patient presented with a nonhealing ulcer of the face, which had been present and increasing in size for over 20 years. On examination, the ulcer covered the entire left side of the face involving the preauricular, infraorbital, and bucco mandibular units of the cheek and the orbit and resulted in loss of vision.56 In another case, a 35-cm BCC on the back of a 65-year-old man recurred after wide local excision and X-ray therapy (XRT), resulting in spinal cord compression.57 Lethal extension to the central nervous system from aggressive scalp BCC has been reported.58,59

Perineural invasion (PNI) is uncommon in BCC and occurs most often in histologically aggressive or recurrent lesions.54 The presence of PNI has been correlated with recurrent lesions, increased duration and size of lesions, and orbital invasion.60 In one series, Niazi and Lamberty identified PNI in less than 0.2% of cases. In that series, perineural BCC was seen most often with recurrent tumors located in the preauricular and malar areas.61 Brown and Perry found the incidence of PNI to be 3% in aggressive BCC cases. This incidence approaches that reported for cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas.62 Leibovitch et al found an incidence rate of 2.74%.63 Ratner et al found a higher incidence in their study (3.8%); however, this was a smaller study.64 Leibovitch et al reported perineural spread in more than 50% of periocular BCCs eventuating in orbital invasion. These tumors required extensive surgery and in some cases exenteration (Fig. 115-5).65 Perineural spread may manifest as pain, paresthesias, weakness, or paralysis. The presence of focal neurologic symptoms at the site of a previously treated skin cancer should raise concern about nerve involvement.

Metastasis of BCC occurs only rarely, with rates varying from 0.0028% to 0.55%.34–36,66–68 Involvement of regional lymph nodes and lungs is most common. Cases of pulmonary metastasis continue to be reported.69 Metastasis to the bone and bone marrow has been reported.70 Aggressive histologic characteristics, including morpheaform features, squamous metaplasia, and PNI, have been identified as risk factors for metastasis.68 Von Domarus et al reported five cases of metastatic BCC in which perineural or intravascular invasion had been noted in three.71 Squamous differentiation was not observed in the primary tumors in the cases they presented but was noted in two of five cases of metastatic cancer. Overall, squamous differentiation was present in 15% of the primary or metastatic tumors from the 170 cases reviewed in that series.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of BCC is accomplished by accurate interpretation of the skin biopsy results. The preferred biopsy methods are shave biopsy, which is often sufficient, and punch biopsy. A sterilized razor blade, which can be precisely manipulated by the operator to adjust the depth of the biopsy specimen, is often superior to a No. 15 scalpel for shave biopsies. A punch biopsy may be useful for flat lesions of morpheaform BCC or for recurrent BCC occurring in a scar. When biopsying a lesion, adequate tissue should be taken. Small, fragmented tissue samples may make diagnosis difficult; potentially compromising the ability to accurately assess BCC subtype and thickness, which can affect treatment choice.72

Histopathology

Histopathologic features vary somewhat with subtype, but most BCCs share some common histologic characteristics. The malignant basal cells have large nuclei and relatively little cytoplasm. Although the nuclei are large, they may not appear atypical. Usually, mitotic figures are absent. Frequently, slit-like retraction of stroma from tumor islands is present, creating peritumoral lacunae that are helpful in histopathologic diagnosis.73 The most common form of BCC is nodular, followed by superficial, then morpheaform. Also, nodular and morpheaform are most commonly found on the head and neck, while superficial is most often found on the trunk region.74

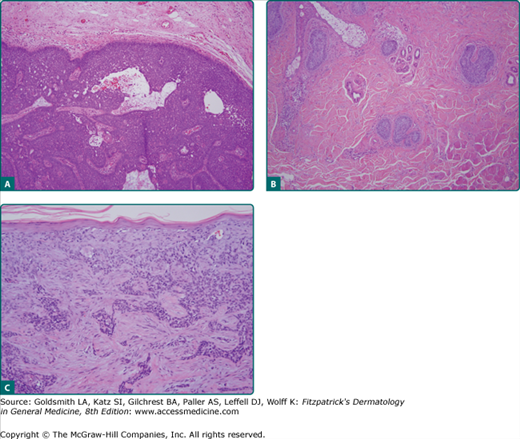

Nodular BCCs account for half of all BCCs and are characterized by nodules of large basophilic cells and stromal retraction (Fig. 115-6A). The term micronodular BCC is used to describe tumors with multiple microscopic nodules smaller than 15 μm (see Fig. 115-6B).73 Clinically, this is the type of BCC that most commonly shows a translucent pearly papule or nodule with a rolled border and telangiectasia. The nodular form of BCC is characterized by discrete nests of basaloid cells in either the papillary or reticular dermis accompanied.1

Pigmented BCC shows histologic features similar to those of nodular BCC but with the addition of melanin.38 Approximately 75% of BCCs contain melanocytes, but only 25% contain large amounts of melanin. The melanocytes are interspersed between tumor cells and contain numerous melanin granules in their cytoplasm and dendrites. Although the tumor cells contain little melanin, numerous melanophages populate the stroma surrounding the tumor.73

Superficial BCC is characterized microscopically by buds of malignant cells extending into the dermis from the basal layer of the epidermis.38 The peripheral layer shows palisading cells. There may be epidermal atrophy, and dermal invasion is usually minimal. There may be a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis. This histologic subtype is encountered most often on the trunk and extremities, but may also appear on the head and neck.73

Morpheaform BCC, also called infiltrative or sclerosing BCC, consists of strands of tumor cells embedded within a dense fibrous stroma (see Fig. 115-6C).73 Tumor cells are closely packed columns and, in some cases, only one to two cells thick enmeshed in a densely collagenized fibrous stroma. Strands of tumor extend deeply into the dermis. The cancer is often larger than the clinical appearance indicates. Recurrent BCC may also demonstrate infiltrating bands and nests of cancer cells embedded within the dense fibrous stroma of scar.

In FEP, long strands of interwoven basiloma cells are embedded in fibrous stroma with abundant collagen.38 Histologically, FEP shows features of reticulated seborrheic keratoses and superficial BCC.73

Basosquamous carcinoma is a form of aggressive growth BCC. It can be confused with squamous cell carcinoma and promotes controversy considering its precise histomorphologic classification as it shows both basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma differentiation in a continuous fashion.1 Histologically, basosquamous carcinoma shows infiltrating jagged tongues of tumor cells admixed with other areas that show squamous intercellular bridge formation and cytoplasmic keratinization.