Abstract

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (pCBCLs) are classified into 3 main categories: primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (PCMZL), primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (DLBCLLT). Detection of monoclonal expression of immunoglobulin light chains (kappa or lambda) is a key diagnostic feature for PCMZL. PCFCL presents with clustered papules and tumors on the head and neck or trunk. Histology shows a follicular, mixed, or diffuse infiltrate of centrocytes and centroblasts. DLBCLLT presents with solitary or multiple plaques and tumors, most often located only on the leg(s). Histology shows a proliferation of large B lymphocytes positive for Bcl-2 and MUM-1, allowing differentiation from diffuse cases of PCFCL. Treatment options for low-grade pCBCLs include primarily “watchful waiting” and local radiotherapy; solitary lesions may be excised surgically. Anti-CD20 antibody may be used in some patients, while systemic chemotherapy is usually only required in patients with high-grade aggressive tumors.

Keywords

cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, cutaneous extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, intravascular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, cutaneous B lymphoblastic lymphoma

- ▪

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas represent a group of lymphomas whose primary site is the skin; they are derived from B lymphocytes in different stages of differentiation. The skin can also be the site of secondary involvement by extracutaneous (usually nodal) B-cell lymphomas

- ▪

Most primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (>80%) are low-grade malignancies, and they are characterized by indolent behavior and a good prognosis

- ▪

Precise classification can be achieved only after a complete synthesis of clinical, histopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular features. The WHO-EORTC and WHO classifications provide the basis for a consistent classification of patients

- ▪

Treatment options for low-grade types include primarily “watchful waiting” and local radiotherapy; when solitary lesions are present, surgical excision is an option. Systemic or intralesional anti-CD20 antibody may be used in some patients, while systemic chemotherapy is only required in patients with high-grade tumors

Introduction

Although B-cell lymphomas represent the majority of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) arising within lymph nodes , they represent a minority of the NHLs whose primary site is the skin . In the classification of cutaneous lymphomas published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous Lymphoma Project Group ( Table 119.1 ), B-cell lymphomas represented 22.5% of all cutaneous lymphomas . The WHO-EORTC classification has been integrated with only minor changes into the WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues published in 2008 and updated in 2016 (see Table 119.1 ) .

| CLASSIFICATION OF B-CELL LYMPHOMAS WITH PRIMARY CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS | |

|---|---|

| WHO-EORTC 2005 | WHO 2008/2016 |

|

|

* Includes cases previously designated as primary cutaneous immunocytoma and primary cutaneous plasmacytoma.

Primary cutaneous lymphomas are defined as malignant lymphomas confined to the skin at presentation after complete staging procedures . In general, most patients with primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (pCBCL) are diagnosed by dermatologists, as extracutaneous symptoms and signs are observed only very rarely at the onset of the disease. Consequently, dermatologists should be conversant with the clinicopathologic features of this group of diseases, in order to be able to establish the diagnosis in its early stages. Additionally, as aggressive treatment modalities are needed only in selected cases, these patients should be managed primarily by dermatologists with special expertise in cutaneous lymphomas.

History

In the past, cutaneous B-cell lymphomas were thought to be invariably secondary, that is, due to dissemination of extracutaneous (usually nodal) B-cell lymphomas to the skin. In the 1980s, it was recognized that B-cell lymphomas whose primary site is the skin, i.e. pCBCLs, represent a distinct group of extranodal lymphomas . The widespread use of immunohistochemical and molecular genetic techniques that can establish clonality, in particular the detection of rearrangements of immunoglobulin genes by PCR (utilizing routine biopsy samples), has shown that some of the cases previously classified as cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphomas harbor a monoclonal population of lymphocytes, thus representing low-grade malignant B-cell lymphomas of the skin .

Epidemiology

For the past several decades, the incidence of pCBCL had been rising, but now appears to have stabilized . pCBCLs may occur more frequently in specific regions of the world. For example, analysis of data from four academic centers in the US showed that they represented only 4.5% of all the cases of primary cutaneous lymphoma registered in those centers . In contrast, pCBCL represented 22.5% of all the cases of primary cutaneous lymphoma in the Dutch and Austrian registries for cutaneous lymphomas .

Regional variations have also been observed with regard to the incidence of specific types of pCBCL. In the two largest series published to date, the relative frequencies of follicle center lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma varied considerably. Follicle center lymphoma represented 71% of all pCBCLs in the Netherlands, but only 41% in Graz; conversely, marginal zone lymphoma represented 42% of all cases of pCBCL in Graz, but only 10% in the Netherlands. On the other hand, the relative frequency of the third most common type of pCBCL, the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, was similar in the two series (~15%), indicating that, in these two series, differences in the relative frequencies were confined to B-cell lymphomas characterized by an indolent behavior. This suggests that these variations may be due, at least in part, to a different classification of patients in different centers.

In addition to differences in diagnostic and classification standards, true regional variations in the incidence of special types of pCBCL may be due to the presence of different etiologic factors. For example, the association between pCBCL and infection with specific Borrelia species in endemic areas has been known for many years (see below and Ch. 74 ). This association may explain, in part, regional differences in the incidence of pCBCLs, but the relatively low percentage of such cases (even in countries with endemic Borrelia infections) suggests that other etiologies are also involved in regional variations.

pCBCL affects adults of both sexes. With the exception of precursor B lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (which only rarely represents an example of true pCBCL), CBCLs are uncommon in children and adolescents.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of pCBCL is unknown. In contrast to the many nodal B-cell lymphomas that have been linked to specific genetic alterations (e.g. nodal follicular lymphomas and interchromosomal 14;18 translocations), there are relatively limited data on the specific genetic features of pCBCLs, especially for low-grade subtypes (for details see below).

Some similarities to the clinicopathologic features observed in B-cell lymphomas arising in the gastric mucosa (so-called mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT] lymphomas) led to the hypothesis that pCBCLs are caused by longstanding antigenic stimulation, possibly due to chronic infection with specific microorganisms. In fact, it has been long established that MALT lymphomas originating in the stomach are linked to chronic antigenic stimulation due to infection with Helicobacter pylori. As previously mentioned, Borrelia spp. are thought to play an etiologic role in a minority of cases of pCBCL, particularly in Europe. In patients from a region in Austria with endemic Borrelia infections, specific DNA sequences of Borrelia were detected in 18% of all cases of pCBCL ; similar findings have been reported from Scotland .

At present, no other microorganism has been convincingly linked to the development of pCBCL. However, it should be noted that pCBCLs have been described in immunosuppressed patients, including those with AIDS and solid organ transplant recipients, and reversible pCBCLs have been observed in patients undergoing therapy with methotrexate (in particular those with rheumatoid arthritis), thus suggesting that immune dysregulation may play a role in the development of this disease .

Clinical Features

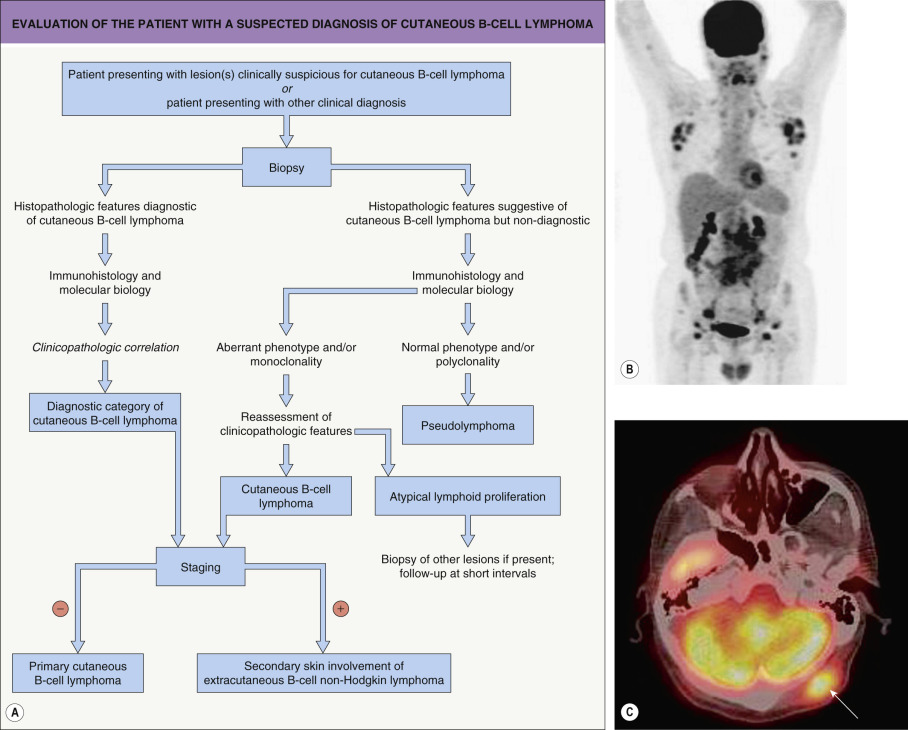

In the WHO-EORTC 2005 and WHO 2008/2016 classification schemes, pCBCLs have been divided into four major types (see Table 119.1 ) . Follicle center lymphoma and marginal zone B-cell lymphoma are characterized by an indolent clinical behavior, whereas diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, and intravascular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical behavior. It must be emphasized that, in addition to pCBCLs, the skin can be a site of secondary involvement for practically all types of extracutaneous (usually nodal) B-cell lymphomas and leukemias. Consequently, complete staging should be performed in all patients with a confirmed diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma involving the skin. This includes a complete blood examination, flow cytometry of peripheral blood, CT examination of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and, if possible, positron emission tomography (PET). Internationally, bone marrow biopsy (with flow cytometry of the aspirate) is still recommended in follicle center lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, and intravascular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, but seems to be of limited value in cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma . In fact, the need for extensive staging investigations in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma is questionable. Likewise, extensive radiologic imaging seems to be superfluous in the follow-up of patients with indolent types of pCBCL confined to the skin . A recommended staging evaluation for patients with CBCL is summarized in Table 119.2 .

| RECOMMENDED STAGING INVESTIGATIONS FOR PATIENTS WITH A CONFIRMED DIAGNOSIS OF B-CELL LYMPHOMA INVOLVING THE SKIN |

| History and physical examination |

|

| Laboratory studies |

|

| Imaging studies |

|

| Additional studies as clinically indicated |

|

* Not required in primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma

** While recommended for follicle center lymphoma and all types of large B-cell lymphoma, in the US bone marrow biopsy has been replaced by PET scan as the latter is a more sensitive test.

Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma

P rimary c utaneous f ollicle c enter l ymphoma (PCFCL) is defined as a neoplastic proliferation of germinal center cells confined to the skin. It represents a common subtype of pCBCL.

Clinically, patients present with solitary or grouped, pink- to plum-colored papules, plaques or tumors, which, especially on the trunk, can be surrounded by patches of erythema ( Figs 119.1 & 119.2 ) . The term Crosti’s lymphoma has been used to denote those patients with a peripheral patch of erythema. Ulceration is uncommon. Occasionally patients present with miliary and/or agminated small papules that can have an acneiform appearance . Preferential locations are the scalp and forehead or the back. The skin lesions are usually asymptomatic, and, as a rule, B symptoms (i.e. fever, night sweats, weight loss) are rare. The serum level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), which is a powerful prognostic factor in systemic lymphomas, is within normal limits.

The prognosis is favorable . Recurrences are observed in up to 50% of patients, but dissemination to lymph nodes or internal organs is rare.

Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma (Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma of the Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue – MALT Lymphoma)

P rimary c utaneous m arginal z one B-cell l ymphoma (PCMZL) has been recognized as a distinct variant of low-grade malignant pCBCL . In the WHO classification of 2008/2016 , it has been grouped with other extranodal marginal zone lymphomas of m ucosa- a ssociated l ymphoid t issue (i.e. MALT lymphomas). Of note, cases classified in the past as primary cutaneous immunocytoma or primary cutaneous plasmacytoma represent examples of PCMZL with prominent lymphoplasmacytic or plasmacytic differentiation, respectively, and the terms cutaneous immunocytoma and cutaneous plasmacytoma are not used in the WHO-EORTC and WHO 2008/2016 classification schemes .

Clinically, patients present with recurrent pink–violet to red–brown papules, plaques, and nodules that favor the extremities (upper > lower) or trunk ( Figs 119.3 & 119.4 ). Generalized lesions can be observed in a small number of patients. Ulceration rarely occurs and skin lesions are usually asymptomatic. As a rule, B symptoms (i.e. fever, night sweats, weight loss) are not present. The serum level of LDH is within normal limits. In some instances, resolution of lesions may be accompanied by secondary anetoderma due to loss of elastic fibers in the area of the tumor infiltrate.

The prognosis of PCMZL is excellent. In a study of 32 patients with PCMZL, none of them developed lymph node or internal involvement during a mean follow-up of more than 4 years .

Of note, PCMZL can arise in areas affected by acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans and it may be linked to infection by Borrelia spp. more frequently than are other types of pCBCL, particularly in Europe .

Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type

Primary cutaneous d iffuse l arge B – c ell l ymphoma, l eg t ype (DLBCLLT), represents a form of pCBCL that is characterized by a predominance of large round cells (centroblasts, immunoblasts) positive for Bcl-2, MUM-1 ( mu ltiple m yeloma oncogene 1 or interferon regulatory factor 4 [expressed by post germinal center B cells and plasma cells]), and FOX-P1 . It occurs almost exclusively in elderly patients, predominantly women.

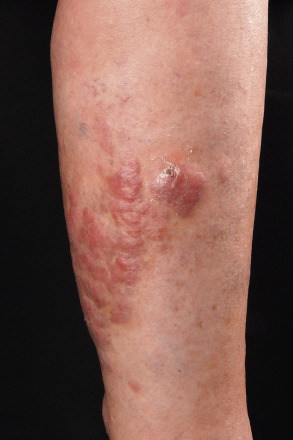

Clinically, patients present with solitary or clustered, erythematous to red–brown nodules, located primarily on the distal aspect of one leg ( Fig. 119.5 ). In some patients, lesions may arise on both lower extremities contemporaneously or within a short interval of time. Ulceration may occur. Small erythematous papules can be seen adjacent to larger nodules. It must be emphasized that in ~20% of patients, tumors with similar morphologic and phenotypic features can arise in areas other than the lower extremities, but the designation DLBCLLT is still applied .

The prognosis of DLBCLLT is less favorable than that of other types of pCBCL, with an estimated disease-specific 5-year survival rate of 40–50% . Molecular data revealed that 9p21 deletions, possibly due to loss-of-function of CDKN2A (encodes p16 and p14 ARF ), are associated with a worse prognosis .

It must be stressed that some patients with nodal large B-cell lymphoma can present with secondary cutaneous lesions located exclusively on the legs, underlying the need for complete staging investigations before a diagnosis of DLBCLLT can be established. The addition of PET scans to CT studies is a useful way of discovering evidence of systemic disease.

Intravascular Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

I ntra v ascular d iffuse l arge B – c ell l ymphoma (IVDLBCL) is a rare malignant proliferation of large B lymphocytes within blood vessels . Most patients have a B-cell phenotype, but a T-cell variant has been reported. In occasional patients, the skin may be the only affected site, although more often there is systemic involvement (including the CNS) from the onset. Clinically, patients present with indurated, erythematous or violaceous patches and plaques, preferentially located on the trunk and thighs and often with prominent telangiectasias. The clinical appearance is not typical of cutaneous lymphoma, and it may sometimes suggest a diagnosis of panniculitis or vascular tumors. Interestingly, in several patients, IVDLBCL was observed to be confined to cherry angioma lesions. The prognosis of IVDLBCL is poor, and the disease usually runs an aggressive course .

Precursor B Lymphoblastic Lymphoma/Leukemia

B-cell lymphoblastic lymphomas/leukemias are malignant proliferations of precursor B lymphocytes. Reports of patients whose primary site is the skin have been rare. It should be emphasized, however, that all patients should be assumed to have, and treated for, systemic disease, even in the absence of documented systemic involvement at the time of presentation.

In contrast to the other cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, this disease shows a clear-cut predilection for children and young adults . Clinically, patients present with solitary large erythematous tumors, commonly located on the head and neck. Patients with primary skin disease often have asymptomatic lesions of a few weeks’ duration. Those with secondary skin lesions may have systemic symptoms, e.g. weight loss, fever, fatigue, night sweats. The serum level of LDH is often elevated, reflecting the aggressive, and often systemic, nature of the disease. The disease is highly aggressive, and the prognosis of untreated patients is poor.

Other Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas

Rare cases of pCBCL do not fit within the subtypes reviewed above. They are therefore placed in the category of primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma, other (WHO-EORTC classification) . In the WHO 2008/2016 classification, these patients are divided amongst several categories, including (but not limited to) large B-cell lymphomas arising in the setting of immune suppression, plasmablastic lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) . Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare lymphoma that usually arises within the oral cavity in patients with severe immunosuppression, especially HIV-related , but can also be observed in immunocompetent patients. It is often associated with infection by EBV.

Pathology

In addition to routine histology and immunohistochemical phenotyping, which when combined are sufficient for the diagnosis of most cases of pCBCL, PCR and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) can also be performed. These latter tests detect rearrangements in immunoglobulin genes, e.g. IGH (encodes the heavy chain), as well as specific chromosomal translocations.

Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma

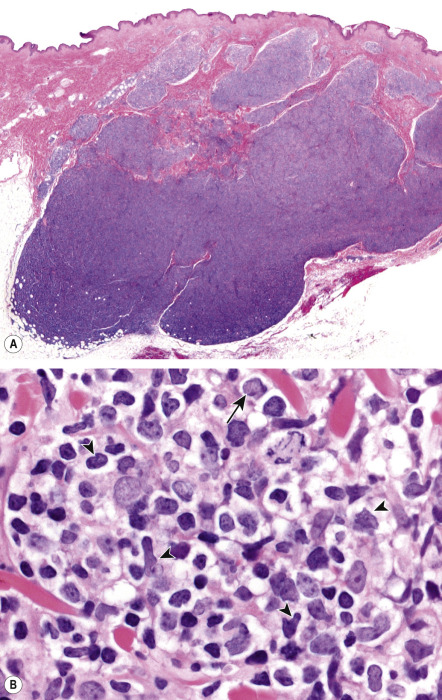

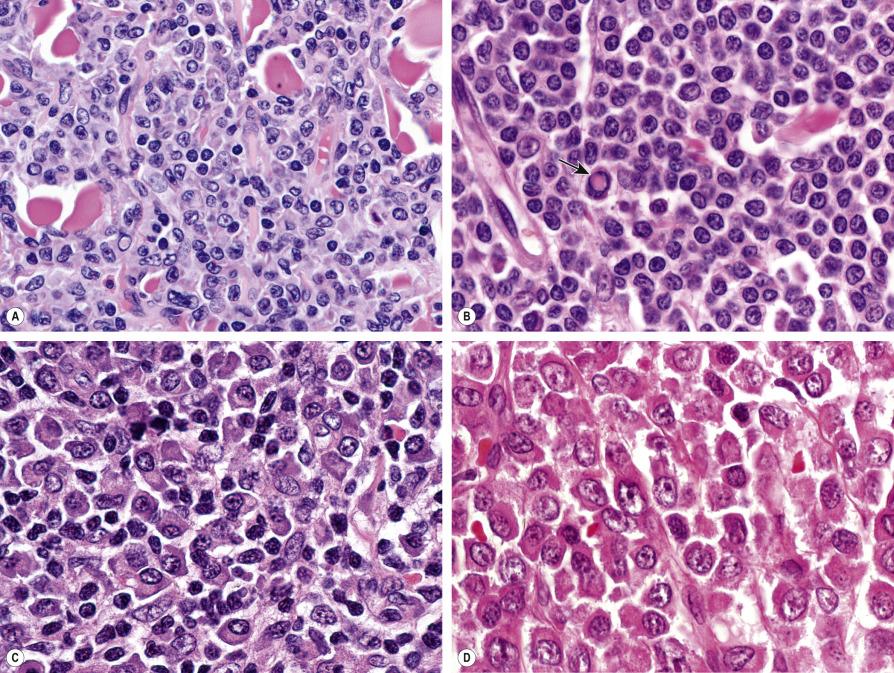

In PCFCL, nodular or diffuse infiltrates are seen within the entire dermis, often extending into the subcutaneous fat ( Fig. 119.6A ) . The epidermis is usually spared. A clear-cut follicular pattern with formation of neoplastic germinal centers was observed in only a minority of cases (25%) in the series from Graz ( Fig. 119.7 ) . However, a higher percentage of cases may show at least some follicular architecture. In those with a follicular pattern, the neoplastic follicles show morphologic features of malignancy, including the presence of a reduced or absent mantle zone, the lack of tingible body macrophages, and a monomorphism of the follicles – so-called “dark” and “clear” areas are no longer recognizable (see Fig. 119.7 [inset]) .

In both the follicular and diffuse variants, centrocytes (small to large, cleaved follicle center cells) predominate within the neoplastic infiltrate ( Fig. 119.6B ) and are admixed with a variable number of centroblasts (large, non-cleaved follicle center cells with prominent nucleoli), immunoblasts, small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and, in some cases, eosinophils and plasma cells. In contrast to nodal FCLs, grading is not used for the classification of PCFCL . On a cytomorphologic basis, some cases of PCFCL with a diffuse pattern of growth and a predominance of large centrocytes have the appearance of a large cell lymphoma, but the prognosis of these cases is similar to that of lesions without the large cell morphology . Patients with a monotonous proliferation of centroblasts and/or immunoblasts should be classified as having diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. An accompanying infiltrate of small T lymphocytes and histiocytes/macrophages is usually present, and, in some instances, these cells can be predominant.

In addition to cases characterized by numerous large cells, morphologic variants of PCFCL include those with a predominant spindle cell morphology, which can simulate sarcomas or other spindle cell tumors histopathologically, thus representing a diagnostic pitfall . Lesions in which a few B-cell blasts are admixed with numerous T lymphocytes have been classified as “T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphomas”, and in the skin probably represent another rare morphologic variant of PCFCL . Of note, when there is nodal involvement with this latter morphologic variant, it is classified as a large B-cell lymphoma.

The tumor cells express B-cell-associated antigens (CD20, CD79a, PAX-5); they are CD5 − and CD43 − (see Table 0.13 for the specificities of CD markers). When follicles are present, they are characterized by an irregular network of CD21 + follicular dendritic cells. Bcl-6 (a marker of germinal center cells and other lymphoid cells) is positive in virtually all cases, irrespective of the pattern of growth. In most cases with a follicular growth pattern, and in a minority of those with a diffuse growth pattern, neoplastic cells also stain positively for CD10. The presence of small clusters of Bcl-6 + cells outside the follicles is considered strongly suggestive of a diagnosis of PCFCL .

In the vast majority of cases, staining for the protein product of BCL-2 (Bcl-2) yields negative results within neoplastic follicles, representing a major difference from follicular lymphomas arising within lymph nodes . A useful, though somewhat counterintuitive, distinguishing immunohistochemical feature is the lower degree of proliferative activity within malignant follicles as detected by the anti-Ki-67 antibody (expressed by proliferating cells), in contrast to the strong Ki-67-positivity in reactive follicles . In cases with large cell morphology (predominance of large cleaved cells), immunohistochemical staining for MUM-1 is either negative or is positive in a minority of neoplastic cells (in contrast to strong expression of MUM-1 by DLBCLLT; see below) . The interchromosomal 14;18 translocation, typically found in nodal follicular lymphomas, is present in a minority of PCFCLs . Therefore, the presence of the 14;18 translocation and/or expression of Bcl-2 should raise suspicion that the patient has a systemic lymphoma involving the skin. Analysis of the genes that encode the joining segment (J H ) and other regions of the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) reveals the presence of a monoclonal rearrangement in the majority of patients (60–70%). When gene expression in PCFCLs was analyzed via cDNA microarrays, a germinal center cell signature pattern was observed.

Analysis of morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular data suggests that follicular lymphomas originating in the lymph nodes and the skin, although characterized by a similar morphologic pattern, have different pathogenic mechanisms.

Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma (Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma of the Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue – MALT Lymphoma)

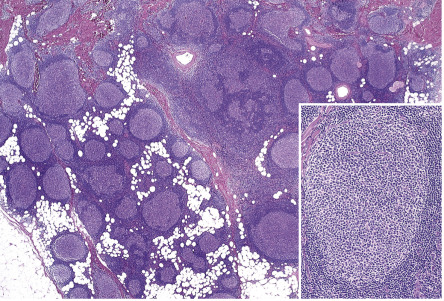

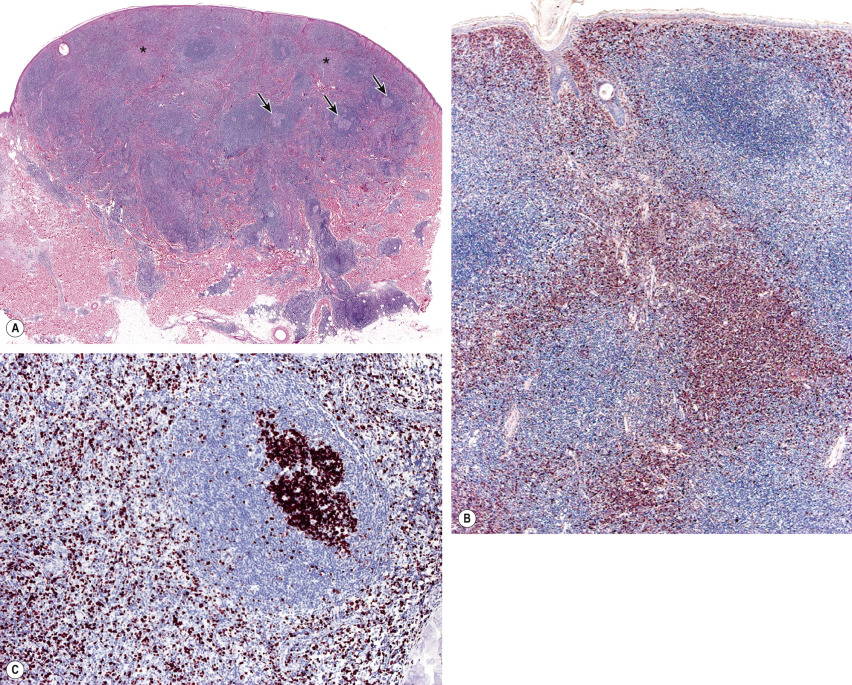

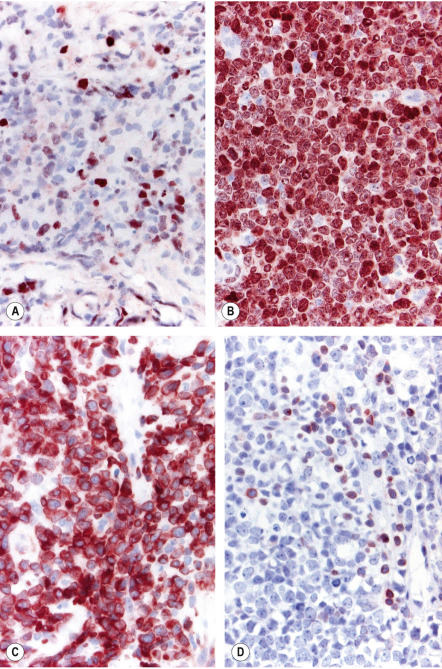

Histology of PCMZL shows a patchy, nodular or diffuse infiltrate involving the dermis and subcutaneous fat. The epidermis is spared. A characteristic pattern can be observed at scanning magnification ( Fig. 119.8A ): nodular infiltrates (sometimes containing reactive germinal centers) are surrounded by a pale-staining population of small- to medium-sized cells with indented nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and abundant pale cytoplasm – variously described as marginal zone cells, centrocyte-like cells, or monocytoid B cells ( Fig. 119.9A ) . In addition, plasma cells (at the margins of the infiltrate), lymphoplasmacytoid cells, small lymphocytes, and occasional large blasts are observed. Eosinophils are also a common finding. In some patients, there may be a granulomatous reaction with epithelioid and giant cells. Cases with a predominance of lymphoplasmacytoid lymphocytes were once classified as cutaneous immunocytomas, but are now considered variants of PCMZL. PAS-positive intranuclear inclusions (Dutcher bodies) are sometimes observed and represent a valuable clue to the diagnosis ( Fig. 119.9B ). Occasionally, the predominant cell type is a plasma cell ( Fig. 119.9C ), and although such cases used to be classified as primary cutaneous plasmacytomas, they are now also considered to be variants of PCMZL . Finally, rare cases are characterized by the predominance of large blastoid cells resembling plasmablasts ( Fig. 119.9D ) .

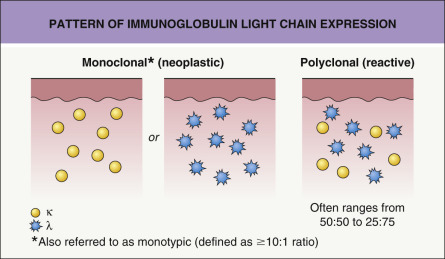

The centrocyte-like cells stain positively for CD20, CD79a, Fc receptor-like 4 (FCRL4/IRTA1) , and Bcl-2; they are negative for CD5, CD10, and Bcl-6. In the overwhelming majority of cases, intracytoplasmic monotypic expression of immunoglobulin light chains (either κ or λ, but not both) can be observed ( Fig. 119.10 ). The monoclonal population of B lymphocytes is often characteristically arranged at the periphery of the cellular aggregates ( Fig. 119.8B ). Staining for proliferation markers also shows increased positivity at the periphery of the nodules (as well as in reactive germinal centers) ( Fig. 119.8C ). IgG4 expression is observed in a minority of cases with plasmacytic differentiation but is not associated with systemic IgG4-related disease . Monoclonal rearrangement of IGH can be detected in the majority of cases (60–80%).

PCMZLs express class-switched immunoglobulins, e.g. the same clone can switch from IgM to IgG or IgA . Although the B lymphocyte changes antibody production from one class to another, the cell retains affinity for the same antigen. PCMZLs are also characterized by aberrant somatic hypermutations allowing binding to different antigens . A minority of PCMZLs express IgM, but this is associated with a higher frequency of extracutaneous dissemination.

A particular translocation, t(14;18)(q32;21), that involves IGH and MALT1 has been detected in a subset of PCMZL (~30%) as well as MALT lymphomas arising in organs other than the skin. In gene expression studies utilizing cDNA microarrays, PCMZLs had a plasma cell signature pattern . Other genetic aberrations include trisomy 3 (with upregulation of FOXP1 ) and rarely an 11;18 or a 3;14 translocation . However, in more than 50% of patients, no molecular abnormalities have been found.

Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type

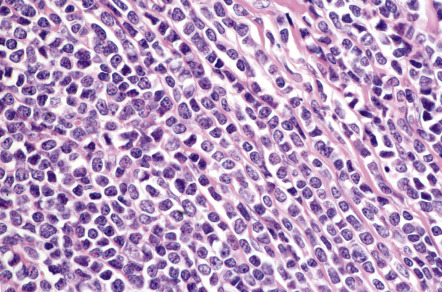

In DLBCLLT, a dense diffuse infiltrate is seen within the dermis and subcutis. The infiltrate usually involves the entire papillary dermis extending to the dermal–epidermal junction. Involvement of the epidermis by clusters of large atypical cells, simulating the Pautrier microabscesses found in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, can be observed in some cases (B-cell epidermotropism), representing a potential diagnostic pitfall . The neoplastic infiltrate consists predominantly of immunoblasts (large round cells with abundant cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli) and centroblasts ( Fig. 119.11 ). Of note, cases of pCBCLs with a predominance of large cleaved cells (i.e. large centrocytes) are classified among the PCFCLs (see above) . Reactive small lymphocytes are usually few in number, and mitoses are frequent. The common finding of immunoglobulin gene hypermutations is evidence that DLBCLLT is a large cell lymphoma, representing post germinal center lymphocytes that originated from lymphocytes of the germinal center.

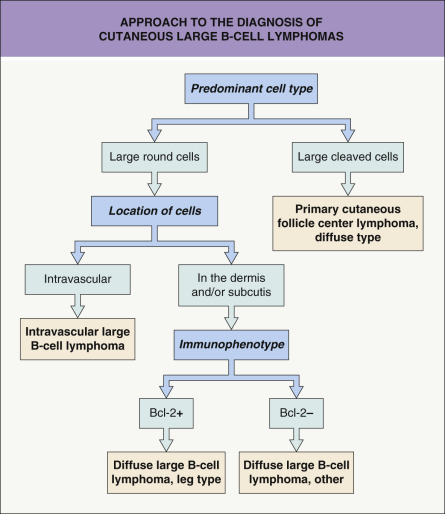

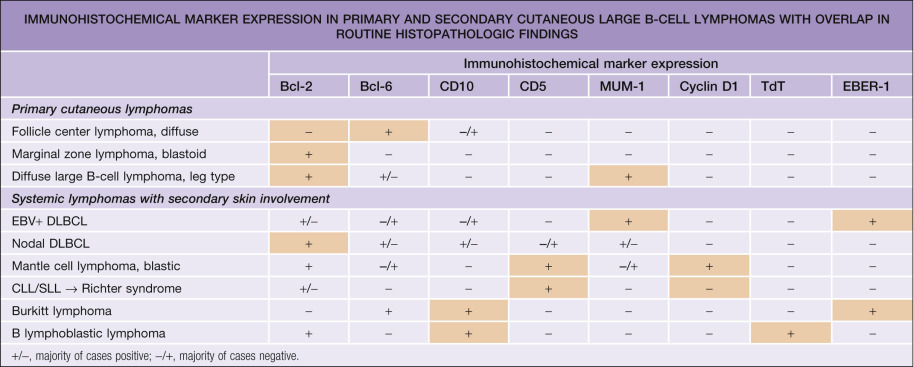

Neoplastic cells are positive for B-cell markers (CD20, CD79a, PAX-5, IgM), but there can be (partial) loss of antigen expression. Bcl-2, MUM-1 (see above), FOX-P1, and MYC are expressed by neoplastic cells in most patients . These markers are useful in the differential diagnosis of DLBCLLT from PCFCL, diffuse type; in the latter, Bcl-2, MUM-1, and FOX-P1 are usually either negative or expressed by a small minority of cells ( Fig. 119.12 ). The tumors demonstrate monoclonal rearrangement of IGH . The interchromosomal 14;18 translocation is not present. An algorithmic approach to the diagnosis of cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphomas is provided in Fig. 119.13 . The differential expression of lymphoid markers in various types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with cutaneous involvement is summarized in Table 119.3 .

Rare cases of otherwise typical cutaneous DLBCLLT show expression of CD30 by neoplastic cells . In nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, CD30 expression was associated with a better prognosis, but data on DLBCLLT are lacking. Hypermethylation of the genes that encode p15 and/or p16 ( CDKN2B , CDKN2A ), resulting in decreased expression of these proteins, has been observed in some patients. 9p21 deletions, possibly leading to loss-of-function of CDKN2A , are associated with a worse prognosis . A worse prognosis has also been noted in patients whose tumors have MYD88 mutations.

Genetic data obtained by FISH or microarray chip technologies have confirmed that DLBCLLTs show clear molecular differences from PCFCL, diffuse type, confirming the need of classifying these cases separately . The molecular profile of DLBCLLT is similar to that observed in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of the lymph nodes, with the signature pattern of an activated B lymphocyte .

Intravascular Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

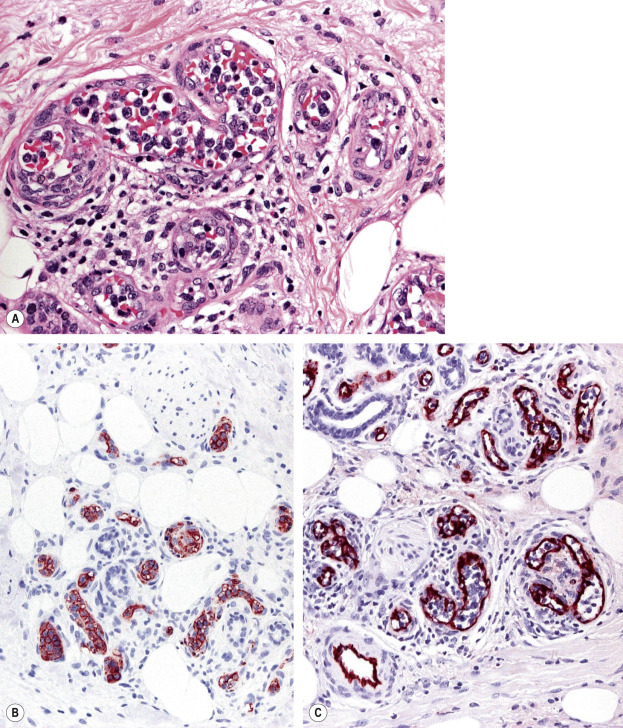

IVDLBCL is characterized by a proliferation of large atypical lymphocytes that fills dilated blood vessels within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues ( Fig. 119.14A ). The malignant cells are large with scanty cytoplasm and often have prominent nucleoli. They are positive for B-cell-associated markers ( Fig. 119.14B ) as well as for Bcl-2, MUM-1 and FOX-P1. Staining with endothelial cell-related antibodies (e.g. CD31, CD34) highlights the characteristic intravascular location of the cells ( Fig. 119.14C ). Molecular analysis shows monoclonal rearrangement of IGH . The genetic profile is similar to that observed in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, activated B cell type.

Precursor B Lymphoblastic Lymphoma/Leukemia

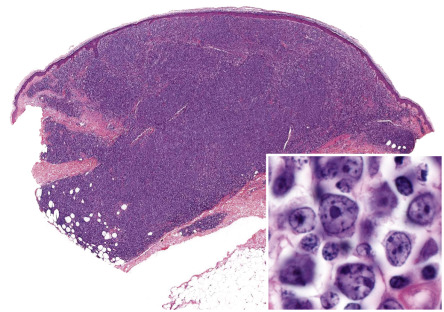

Histologically, precursor B lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia shows a monomorphous proliferation of medium-sized cells with scanty cytoplasm and round or convoluted nuclei with fine chromatin ( Fig. 119.15 ). A “starry sky” pattern is commonly seen at low power, due to the presence of macrophages with inclusion bodies (“tingible bodies”). Another characteristic feature is the arrangement of neoplastic cells in a “mosaic-stone” pattern. Mitoses and necrotic cells are abundant. It must be stressed that histologic features alone do not allow differentiation of lymphoblastic lymphomas of B-cell phenotype from those of T-cell lineage. Immunohistology demonstrates positive staining for TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase; present on precursor T and B cells), PAX-5, CD10, and the cytoplasmic µ-chain of immunoglobulins, and in most cases, CD20 and CD79a. CD20 is negative in the pre-pre-B-cell variant, which is CD34 + . Molecular analyses usually show a monoclonal rearrangement of IGH and a polyclonal pattern for T-cell receptor genes ( TCR ), but a lack of rearrangement of IGH or monoclonal rearrangement of both TCR and IGH may be observed.

Other Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas

Plasmablastic lymphoma is characterized by a proliferation of plasmablasts with large eccentric nuclei, abundant cytoplasm, and prominent nucleoli. While the tumor cells may appear lymphoid, they stain like plasma cells. They are positive for CD38, CD138 and MUM-1, but negative for CD20; they express monotypic immunoglobulin light chains. In situ hybridization for EBV (EBER-1) is positive in the vast majority of cases.

Differential Diagnosis

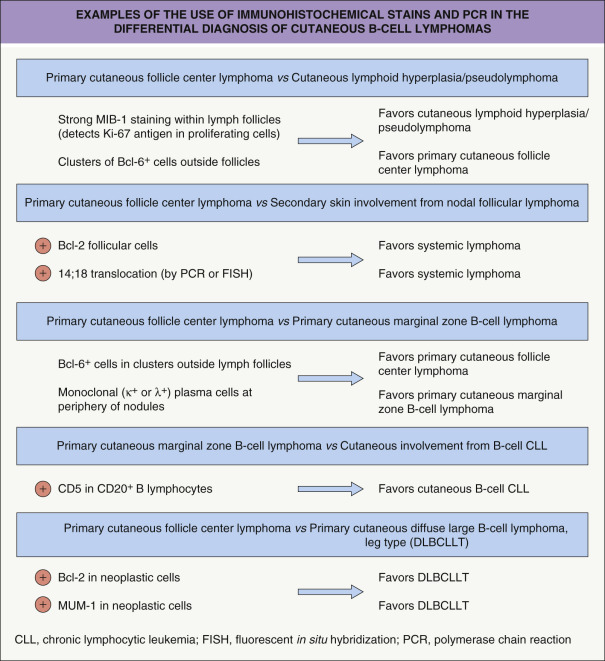

Although differential diagnoses of pCBCLs vary according to the type of lymphoma, in general they include inflammatory processes that may simulate malignant lymphomas clinically and/or histopathologically, referred to as cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphocytoma cutis or “pseudolymphoma” (see Ch. 121 ). It must be emphasized that a definitive diagnosis of pCBCL can be reached only after careful examination of the clinical, histopathologic, immunophenotypic and molecular features; in some cases, only repeated examination of the patient and sequential biopsy specimens will allow the correct classification . A schematic diagram with examples of the use of immunohistochemical stains and PCR in the differential diagnosis of pCBCLs is presented in Fig. 119.16 .

Patients for whom no definitive diagnosis can be established at the time of presentation should provisionally be classified as having “cutaneous atypical lymphoid proliferation of B-cell lineage”, and they should be re-examined at regular intervals . A complete staging investigation does not belong in the diagnostic evaluation of these patients; that is, patients without a definitive diagnosis of CBCL should not be screened for extracutaneous disease until the diagnosis is established with certainty . In contrast, once the diagnosis of CBCL has been established, complete staging is mandatory, as clinicopathologic features alone do not allow the differentiation of primary from secondary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (see Table 119.2 ). A diagnostic algorithm for evaluation of patients at first presentation is provided in Fig. 119.17 .

In the following section, the major differential diagnoses of each of the main types of pCBCL are outlined separately, as they differ according to the lymphoma type.

PCFCL with a follicular pattern of growth should be differentiated from B-cell pseudolymphomas with prominent germinal centers, such as Borrelia -induced lymphocytoma cutis (cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia) . Lymphocytoma cutis can be triggered by a number of stimuli, including arthropod bites, vaccinations, tattoos and drugs, and it has a predilection for particular body sites such as the earlobes, nipples, and scrotum . Clinically, lesions are usually solitary and relatively small. Although histologically a follicular pattern is almost always observed, germinal centers in lymphocytoma cutis are reactive, and they are accompanied by inflammatory infiltrates with small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and often eosinophils . The germinal centers in Borrelia -induced lymphocytoma cutis are often devoid of a clear-cut mantle, but they are characterized by the presence of many tingible body macrophages, “clear” and “dark” areas, and a normal (high) proliferation rate .

Rare cases of cutaneous PCMZL can have a prominent presence of reactive germinal centers, and they should be differentiated from the follicular type of PCFCL. In these cases, so-called follicular colonization by neoplastic marginal zone cells can indeed cause significant problems in histopathologic differential diagnosis, similar to what happens in B-cell lymphomas of the MALT type. However, the overall architecture of the infiltrate, the presence of a population of monoclonal plasma cells belonging to the neoplastic clone, and the negativity of neoplastic cells for CD10 and Bcl-6 usually allow the diagnosis of cutaneous PCMZL to be established.

As mentioned previously, secondary cutaneous involvement by primary extracutaneous follicular lymphomas has morphologic and phenotypic features similar or identical to those observed in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, except for the usual positivity of neoplastic cells for Bcl-2 in secondary cutaneous lesions. Consequently, the occurrence of a cutaneous follicular lymphoma with clear-cut positivity for Bcl-2 within neoplastic follicles should be considered as a hint (although exceptions can be encountered) for the diagnosis of secondary skin lesions of nodal lymphoma.

The differential diagnosis of PCMZL consists primarily of reactive processes and other types of low-grade pCBCL. Benign, reactive processes do not have monotypic restriction of immunoglobulin light chain expression, in contrast to what is observed in the great majority of cases of PCMZL. PCFCL, diffuse type, can be differentiated from PCMZL by the architectural pattern and cytomorphology, with the former being characterized by a diffuse infiltrate of B lymphocytes with a predominance of centrocytes and centroblasts. Moreover, in contrast to PCMZL, neoplastic cells in PCFCL express Bcl-6.

PCMZL should also be distinguished from secondary cutaneous lesions of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL), a condition in which neoplastic B lymphocytes display positivity for CD20, CD23 and CD43, and usually for CD5. Helpful diagnostic features are: (1) the absence, in B-CLL, of plasma cells belonging to the neoplastic clone; and (2) the positivity for CD5 observed in most cases of cutaneous B-CLL, but practically never in PCMZL. CD20 + /CD5 + infiltrates are also seen in secondary skin involvement from mantle cell lymphoma, but in contrast to CLL, mantle cell lymphoma is usually positive for cyclin D1 and negative for CD23 (rare cases of mantle cell lymphoma that are negative for cyclin D1 are positive for SOX11).

PCMZL with prominent plasma cell differentiation must be differentiated from reactive plasma cell proliferations and from inflammatory pseudotumors (plasma cell granulomas). In reactive conditions, plasma cells are not atypical, and they display a polyclonal pattern of immunoglobulin light chain expression. Besides inflammatory pseudotumors, reactive skin diseases with a predominance of plasma cells are very rare, with the exception of lesions arising on mucosal surfaces, spirochetal infections (e.g. syphilis, pinta, yaws, acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans), and cutaneous and systemic plasmacytosis. The latter disorder usually displays a polyclonal pattern of immunoglobulin light chain expression, but rarely monoclonality has been reported . A silver stain (e.g. Warthin–Starry) or immunohistochemical staining for Treponema pallidum can help to highlight the microorganisms in cases of syphilis (see Fig. 0.33 ). The rare entity pretibial lymphoplasmacytic plaque in children is characterized by a polyclonal pattern of the plasma cells.

DLBCLLT must be differentiated from a number of entities, including cutaneous involvement from systemic lymphomas as well as specific infiltrates of acute myelogenous leukemia and non-lymphoid tumors (e.g. solid organ metastases; see Ch. 122 ). The clinicopathologic pattern together with phenotypic and molecular features allow correct classification of these lesions in most instances. In order to avoid diagnostic errors, detailed immunophenotyping is mandatory in all cases of cutaneous lymphoma, especially in those showing medium- to large-sized cell morphology.

The differential diagnosis of IVDLBCL is not a problem in typical cases. The large number of atypical cells within blood vessels is pathognomonic of this condition. Distinction between T- and B-cell types cannot be achieved on morphologic grounds alone. Rare cases of intralymphatic anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma (ALCL) are characterized by a proliferation of neoplastic CD30 + T cells within lymphatic vessels . This disorder represents a variant of ALCL and has similar phenotypic and prognostic features . IVDLBCL should also be distinguished from reactive disorders characterized by an intravascular proliferation of atypical cells, in particular intralymphatic histiocytosis (IH) and benign intralymphatic proliferation of T-cell lymphoid blasts (BIPTCLB). IH occurs in association with chronic cutaneous infections and systemic disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Within the dermis, lymphatic vessels that stain positively for podoplanin contain intraluminal collections of histiocytes (CD68 + , CD20 − , CD3 − ). Of note, focal areas of IH can be an incidental finding. BIPTCLB is a rare entity observed in a wide range of cutaneous and extracutaneous disorders from pyogenic granuloma to appendicitis. As in IH, the lymphatic vessels are affected.

Cases of precursor B lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia should be differentiated from other cutaneous lymphomas/leukemias and from non-lymphoid tumors such as Ewing sarcoma and small cell lung carcinoma. Positivity for TdT represents the most important immunohistochemical feature for the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoblastic lymphoma. Histologic features of cutaneous lesions do not allow the differentiation of T-cell from B-cell lymphoblastic lymphomas, thus emphasizing the importance of complete immunophenotypic and genotypic analyses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree