Axillary Lymph Node Dissection

Elizabeth A. Shaughnessy

The axillary lymph node dissection emerged as a procedure separate from mastectomy when lumpectomy (or partial mastectomy or segmentectomy or tylectomy) became an established option for breast cancer patients with focal, resectable disease. The status of the axilla constitutes a stronger prognostic indicator than the tumor size (1); hence, knowledge of the extent of axillary involvement is critical in staging and, by inference, in treatment.

Historically, advocates for complete lymph node removal in the surgical management of disease date back to the 16th century. Our more modern surgical heritage extends back to Halsted, who advocated a complete axillary lymph node removal in his report of the radical mastectomy. He was strongly influenced by his colleague Charles Moore, whose concept of disease transmission in continuity via the lymphatics was adopted by Halsted in his development of the radical mastectomy (2,3). His publication of long-term survival following his results led to the foundation of the scientific method as applied to the field of surgery, which paved the way for clinical trials.

The advent of the sentinel node as a tool in the decision for further axillary management has led to fewer axillary lymph node dissections. This was the ultimate intent for the patient, since the full dissection is associated with potential lymphatic, neural, and vascular complications. The completion of an axillary lymph node dissection following a prior sentinel node biopsy lends further challenge to the surgical process, depending on the extent of the inflammatory reaction. Those currently in training and those who will train in the future will enter the workforce with less working familiarity with the process of an axillary lymph node dissection. It is incumbent upon those who possess a working familiarity to communicate it to the surgical generations of the future, learning from those more familiar with its nuances and challenges.

An axillary lymph node dissection is performed within the context of a modified radical mastectomy for the treatment of inflammatory breast cancer and within the context of known positive ipsilateral lymph nodes for early breast cancer. In the context of a prior sentinel lymph node biopsy, this would be indicated by adenocarcinoma within the node. The NSABP B-32 trial randomized patients to completion axillary lymph

node dissection versus completion axillary lymph node dissection only with the presence of a positive sentinel lymph node (4). Among those with any positive sentinel nodes, further nodal involvement was identified in 29% of the patients. With the growing incorporation of ultrasound as applied to breast, the identification of suspicious ipsilateral nodes has led to greater frequency in fine needle aspiration under ultrasound guidance of these nodes prior to any surgical procedure. This may lessen the overall cost of operative management, since a positive result would prompt an axillary lymph node dissection, whereas a negative result would prompt at least a sentinel lymph node biopsy.

node dissection versus completion axillary lymph node dissection only with the presence of a positive sentinel lymph node (4). Among those with any positive sentinel nodes, further nodal involvement was identified in 29% of the patients. With the growing incorporation of ultrasound as applied to breast, the identification of suspicious ipsilateral nodes has led to greater frequency in fine needle aspiration under ultrasound guidance of these nodes prior to any surgical procedure. This may lessen the overall cost of operative management, since a positive result would prompt an axillary lymph node dissection, whereas a negative result would prompt at least a sentinel lymph node biopsy.

On rare occasion, the injection of radioisotope or blue dye in the context of an axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy may fail to migrate to the axilla despite maneuvers to enhance such (warmth, massage, injection of parenchyma with sterile saline). The incidence of failure of these lymphatic markers to migrate has been documented as less than 3% in the context of community surgeons (4). Knowledge of axillary nodal involvement, as the prognostic factor of greatest impact, is needed for adequate staging; a completion axillary lymph node dissection would generally then be the default procedure.

The role of axillary lymph node dissection is under scrutiny relative to its role in early breast cancer. The question of whether to complete the axillary dissection becomes more complicated when dealing with a micrometastasis or single cells of those with restricted axillary access because of marked reduction in range of motion. In these cases, one may be unable to complete an axillary lymph node dissection, in the context of a positive sentinel lymph node, or one may pause to question the relative benefit. Certainly, adequate treatment of the axilla is indicated regardless, with radiotherapy often playing a larger role in regional control of the axilla (5).

The finding of negative sentinel node(s), if done appropriately, would not prompt a completion axillary lymph node dissection unless the operator was not confident of his or her ability to identify a sentinel lymph node, as when a surgeon may be in his or her learning curve or when circumstances bring the accuracy of the sentinel lymph node into question. Furthermore, surgeons today generally do not perform an axillary lymph node dissection in the context of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), unless a sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed that demonstrated nodal metastases. Performance of a sentinel lymph node biopsy with the finding of comedo-type DCIS is supported (6), but performance of a sentinel lymph node before a mastectomy for extensive DCIS is also well founded.

In the context of preoperative planning, assessment of the axilla, by either ultrasound and fine needle aspiration (FNA) or prior sentinel lymph node biopsy, may have taken place. There is a role for intraoperative sentinel node assessment, either by frozen section or by touch prep cytology, with completion axillary lymph node dissection to follow if positive. Known nodal involvement prompts studies to assess the extent of disease since nodal involvement is associated with a higher rate of distant disease (7); metastatic disease generally prompts systemic therapy, with surgical management only in select circumstances (8,9). These tests would include a bone scan and computed tomography scans of the chest and abdomen to assess the bone, lungs, and liver. Brain magnetic resonance imaging would be ordered selectively on the basis of patient symptoms.

Early education of the patient regarding drain management helps both to better prepare the patient and to support family or friends for the postoperative state. Finally, in scheduling a patient who has undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy for surgery that will include a full axillary lymph node dissection, extra time needs to be budgeted beyond what is typical for that individual surgeon. A robust response to chemotherapy may generate an extensive scarring within the axilla, thickening fascial layers or obscuring anatomic landmarks that ultimately will slow surgical progress and dissection.

Finally, a discussion with the anesthesiologist prior to surgery may be warranted if you desire the patient not to be paralyzed during the course of surgery. If the patient is not paralyzed, testing large motor nerves can be done definitively.

Relevant Anatomy

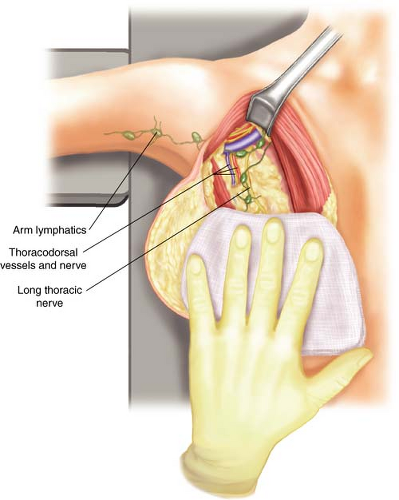

The axilla to be dissected is contained within an upside-down pyramid that runs from the axillary vein as the base and the walls of the pyramid from the serratus medially, the latissimus laterally, and the teres major posteriorally. The long thoracic nerve runs medially on the serratus at the level of the axillary vein and the teres major. The thoracodorsal nerve typically runs along the medial side of the thoracodorsal vessels and can be identified beginning at the takeoff of the thoracodorsal vessels from the axillary vein (Fig. 12.1).

Positioning

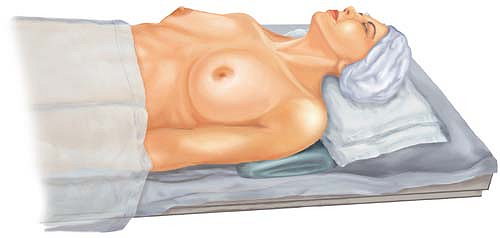

The positioning of the patient is key to one’s success in both intraoperative exposure and postoperative patient recovery. Typically, the patient is placed in the supine position, with the ipsilateral arm on an armboard, at approximately a right angle to the body. Including the ipsilateral arm in the prepped field gives greater flexibility in future intraoperative exposure. Be attentive to the patient’s preoperative upright posture. The patient with somewhat rounded, stooped shoulders may benefit from an additional blanket under the shoulders to bring the shoulders into their usual position, while the patient is supine (Fig. 12.2). If the shoulders are brought more forward with a blanket, then

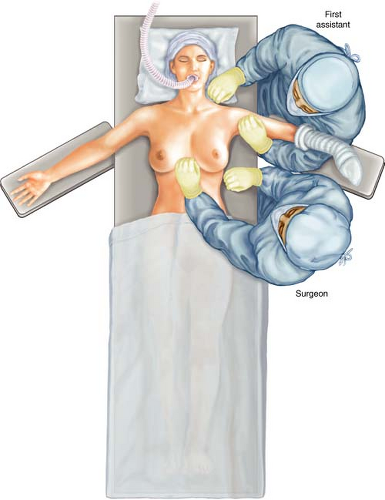

additional supplemental padding should be placed on the arm boards to raise the upper extremities to the same level as the shoulder. This maneuver helps to prevent pulling along the nerves of the brachial plexus (Fig. 12.3).

additional supplemental padding should be placed on the arm boards to raise the upper extremities to the same level as the shoulder. This maneuver helps to prevent pulling along the nerves of the brachial plexus (Fig. 12.3).

I prefer the body to be positioned along the side of the table on the side to be approached operatively. Finally, for potential maneuverability medially under the pectoralis muscle, I position a rigid ether screen at the head of the operating table, with the crossing bar at approximately the level of the nose. This bar can be used later for suspending the arm brought up anterior to the face during the nodal dissection, if the pectoralis minor muscle is far more medial under the pectoralis major muscle (Fig. 12.4). The operating surgeon stands next to the operating table next to the thorax, whereas the assistant stands above the armboard, next to the head (Fig. 12.5).

Special Equipment

The special equipment may vary depending on the patient’s anatomy or the needs of the case, especially if combined with other procedures. A headlamp should be considered if the patient is a larger individual and there will be an incision for the axillary lymph node dissection separate from an incision for the breast; it may be considered in the patient having a skin-sparing incision, where there will not be a separate incision for the axilla.

I prefer a right angle for blunt dissection, utilizing electrocautery for most dissections. If reduction of drainage is desired, the division of tissue can also be approached by using the harmonic scalpel to seal the lymphatics in the course of the dissection.

This usually takes more time; furthermore, there is a learning curve in terms of speed of use and coordination with one’s assistant. The technique can be particularly valuable when approaching surgery in patients in whom you may be having difficulty with surgical oozing, who have a pacemaker or automated implantable cardioverter–defibrillator and one is concerned about electrical stimuli, or those who may be at risk of bleeding as they were on clopidogrel, warfarin, or aspirin.

This usually takes more time; furthermore, there is a learning curve in terms of speed of use and coordination with one’s assistant. The technique can be particularly valuable when approaching surgery in patients in whom you may be having difficulty with surgical oozing, who have a pacemaker or automated implantable cardioverter–defibrillator and one is concerned about electrical stimuli, or those who may be at risk of bleeding as they were on clopidogrel, warfarin, or aspirin.

Incision

The incision utilized may vary greatly, depending on the surgical management of the breast. As mentioned earlier, should a skin-sparing incision be used or should the patient’s breast skin envelope remaining after mastectomy be of sufficient size, the opening from the mastectomy can be positioned over the axilla so as to allow the entire dissection through that opening; a separate incision may not be necessary. Similarly, within the incision utilized for a modified radical mastectomy done without skin-sparing, the full axillary lymph node dissection may be performed without additional incision (Fig. 12.6).

Alternately, a skin-sparing incision does not always allow for the dissection, and a separate counter incision is made in the axilla or as an extension of a prior sentinel lymph node biopsy incision. The incision made would be the same as one would use in conjunction with lumpectomy, extending from the anterior to the posterior axillary fold, preferably below the area bearing hair, in a preexisting skin fold (Fig. 12.7). When a separate incision is necessary, skin flaps need to be raised superiorly to the axillary fold and inferiorly to approximately the lateral extent of the inframammary fold.

Defining Axillary Extent

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree