Autologous Reconstruction: TRAM Flap

Luis O. Vásconez

Dean R. Cerio

Introduction

Breast reconstruction has evolved considerably. Initially, reconstructive efforts created an imperfect product, consisting only of a breast mound with an implant. This has now developed into a most satisfactory and acceptable method, where following the extirpation of either one or both breasts, the reconstructed breast is soft, pliable, symmetric, and often more aesthetically pleasing than the original breast. This is particularly true with the use of autologous tissue in the form of the TRAM flap. In addition, experience has demonstrated that as the years progress, patient satisfaction increases with an autologous reconstruction, which is different from the experience of patients who undergo reconstruction with expanders or implants (1).

Patients who develop breast cancer, have had previous pregnancies, and have an abdominal convexity are excellent candidates for autologous breast reconstruction. The procedure is very well accepted by the patient because of the additional benefit of an improved body contour with the abdominoplasty effect. Whenever one uses an implant for reconstruction of the breast, be this preceded by an expander or even with the use of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap for the additional padding, over a period of time, the implant is subject to a number of changes that interfere with the aesthetic result of the reconstruction. These changes consist of capsular contracture, which brings the implant upward; rupture of the implant, be this saline, or silicone; or malposition of the implant, usually in a position more lateral than one would wish, which may interfere with the proper movement of the arm. Moreover, it is impossible to recreate the teardrop shape of the breast, even despite the use of so-called anatomically shaped implants. This is so because implants have a tendency to become rounded, creating an unattractive convexity in the infraclavicular area. To avert this potential distorted appearance, whenever reconstruction is done with implants, it is advisable that one consider a symmetry procedure with an implant for the opposite normal breast.

Advantages and Disadvantages of TRAM Reconstruction

Autologous reconstruction has both advantages and disadvantages. The advantages are clear. The reconstructed breast is usually lasting, staying soft and symmetric, and the same size over time (except for weight changes). The disadvantages include a longer operating time, longer hospitalization, and a new breast mound that is devoid of sensibility. A TRAM reconstruction creates an additional scar in the lower abdomen, although this is compensated for by the abdominoplasty effect, and there is the rare possibility of flap loss.

Autologous breast reconstruction can be performed with the “conventional method,” which maintains its vascular attachment through the superior epigastric vessels, or by the “free TRAM,” which divides all attachments of the flap. The deep inferior epigastric vessels are then anastamosed with the use of the microscope to the internal mammary artery and vein.

We will emphasize the conventional TRAM flap, but we will also mention the microvascular methods.

Immediate Versus Delayed Breast Reconstruction

At our Breast Center, it is our experience that when patients are offered immediate reconstruction following a skin-sparing mastectomy, they accept it readily and are very pleased with the decision and eventual results. There is a considerable amount of literature indicating the positive and beneficial psychological effects of immediate breast reconstruction, particularly when it is done with safety and results in a symmetric and aesthetically pleasing breast (2). Presently, it is not unusual for patients to request a prophylactic skin-sparing mastectomy on the opposite unaffected side at the same operative setting (3). A bilateral breast reconstruction with autologous tissue is then performed.

Questions that patients and oncologists often ask include the following:

“Will reconstruction hide or delay the detection of recurrent breast cancer?”

“Will reconstruction delay the beginning of adjuvant chemotherapy?”

“Is radiation therapy precluded in the reconstructed TRAM flap?”

The answers to these questions are clear and factual. Breast reconstruction with the TRAM flap does not interfere with the detection of possible cancer recurrence in a palpable postoperative mass (4). A recurrence, if it occurs, usually appears at the subcutaneous tissue level along the scar, in a similar location to the primary tumor (5). This is easily detectable by palpation, although a number of breast centers are performing postoperative magnetic resonance examinations. What may occur in 14% of reconstructions is the development of a palpable lump due to fat necrosis (6). This can be easily distinguished from cancer recurrence because it appears shortly after the operation. It can be confirmed very easily by the use of fine needle aspiration. The answer to the second question is also clear. Chemotherapy is instituted within 8 weeks following breast reconstruction, which is the timing followed by most breast centers. Reconstruction should, therefore, not delay the start of adjuvant chemotherapy. Although a wound problem could develop and persist long enough to delay the start of adjuvant chemotherapy beyond this time frame, the literature shows no difference in survival between patients given chemotherapy at 3 weeks and those given chemotherapy at 12 weeks (7). As far as radiotherapy, the answer is also clear, but not totally satisfactory. If one knows beforehand that the patient is to receive postmastectomy radiotherapy, it is best to delay the reconstruction until at least 3 months following completion of the radiotherapy. This is because radiotherapy will usually shrink and produce a certain amount of fibrosis of the reconstructed breast, thus diminishing any symmetry obtained. If the oncologic surgeon indicates intraoperatively that because of the proximity of the tumor to the pectoralis major fascia, he or she is going to advise radiotherapy, and the reconstructive surgery has already begun by elevating the TRAM flap, it is advisable that the reconstructed breast be made larger than the opposite breast in anticipation of a

certain amount of shrinkage that may occur (in our breast unit, the mastectomy and reconstruction is begun simultaneously with two sets of instruments and two separate operating teams). It should be noted that with newer methods of radiotherapy, fibrosis and shrinkage of the breast have decreased considerably.

certain amount of shrinkage that may occur (in our breast unit, the mastectomy and reconstruction is begun simultaneously with two sets of instruments and two separate operating teams). It should be noted that with newer methods of radiotherapy, fibrosis and shrinkage of the breast have decreased considerably.

Immediate reconstruction is not indicated for patients with systemic diseases that would make reconstruction more hazardous, such as those on steroids or with uncontrolled diabetes.

In patients with large tumors who receive preoperative chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, immediate reconstruction is appropriate, although it is performed with caution, with the expectation of wound healing problems in both the reconstructed breast and the abdominal wound. In patients with postlumpectomy, postradiation, persistent or recurrent tumors, immediate reconstruction is essential, with either a latissimus dorsi or a TRAM flap, because delayed healing of the postradiation wound is likely to occur in any alternative reconstructive effort other than bringing fresh tissue with its own blood supply.

Delayed reconstruction is also a satisfactory option, although it has the obvious disadvantages of an additional operative procedure and a second hospitalization. Nonetheless, the safety and the aesthetic result is similar to the one obtained with immediate reconstruction (8). It does require additional expertise on the part of the reconstructive surgeon to shape the flap to obtain symmetry with the opposite breast. This is also true if one is doing a bilateral reconstruction, because the mastectomy, which usually has been done through a transverse incision, and the contralateral prophylactic mastectomy, which is usually a skin-sparing mastectomy, have differing incisions that make it more challenging to achieve symmetry.

Conventional TRAM Flap

The transverse abdominal myocutaneous (TRAM flap) is the most commonly used method of autologous reconstruction of the breast. It remains the standard, although in more sophisticated breast centers, it is being replaced by the microvascular free TRAM or the DIEP flap. Regardless of how it is done, autologous reconstruction produces the most natural result with symmetry of the contralateral breast in most cases. However, it does require an operating time of approximately 4 to 5 hours and a hospitalization as long as 3 to 5 days.

Conventional TRAM: Blood Supply

The superficial and deep epigastric vessels and the segmental intercostal vessels form the blood supply to the abdominal wall. The deep system is formed by the epigastric arcade, which is vertically oriented at the deep portion of the rectus abdominis muscle, between the superior epigastric and the deep inferior epigastric vessels. In addition, we have the segmental intercostal vessels, which are more horizontally oriented and travel deep to the internal oblique muscle and fascia to anastomoses with the epigastric arcade on the deep portion of the rectus muscle. The nerve supply travels in a segmental fashion with the intercostal vessels. The epigastric arcade branches into segmental perforators that pierce the muscle and the overlying anterior rectus sheath. For the conventional TRAM, the most important perforator is in the periumbilical area, approximately 2 cm below the umbilicus. In this operation, one divides the deep inferior epigastric vessels and the periumbilical perforator, supplied by the superior epigastric vessel via the epigastric arcade, the flap (see Fig. 25.2B). Obviously,

the segmental intercostal vessels and nerves to the rectus abdominis muscle are divided as one elevates the flap. It is easy to see the perforator vessels on the anterior rectus sheath. In fact, they should be noted so that they can serve as a guide to the underlying vessels, which have to be preserved in the elevation of the TRAM flap (Fig. 28.1). The superficial and the deep venous system have valves that prevent the reflux of blood (except in patients with cirrhosis, in which one sees the caput medusa due to the incompetence of the venous system) (9).

the segmental intercostal vessels and nerves to the rectus abdominis muscle are divided as one elevates the flap. It is easy to see the perforator vessels on the anterior rectus sheath. In fact, they should be noted so that they can serve as a guide to the underlying vessels, which have to be preserved in the elevation of the TRAM flap (Fig. 28.1). The superficial and the deep venous system have valves that prevent the reflux of blood (except in patients with cirrhosis, in which one sees the caput medusa due to the incompetence of the venous system) (9).

Elevation of the TRAM Flap

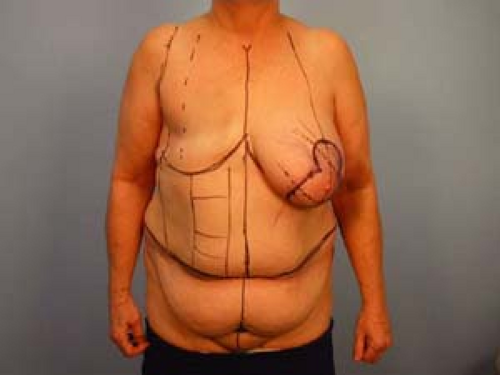

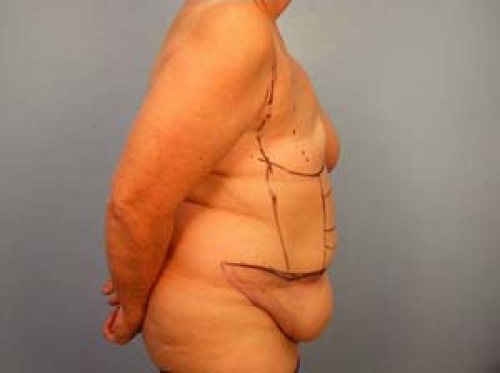

The upper incision is placed at the umbilicus to include the very important periumbilical perforator. The lower incision is made suprapubically as for an aesthetic abdominoplasty, which then gently curves upward and extends as far laterally as necessary (Figs. 28.2 and 28.3). Variations of the incision include a higher placement of the flap, particularly in very obese patients who may have an abdominal panniculus that extends below the suprapubic region. The outline should never be placed below the umbilicus in an effort to maintain the scar at the lowest possible level. Such a low outline may result in the exclusion of the periumbilical perforator, which may lead to flap necrosis.

The upper incision is performed first after one circumscribes the umbilicus and maintains it in place (Fig. 28.4). It is not necessary to bevel the incision. Dissection extends down to the anterior rectus sheath and the external oblique aponeurosis. The upper abdominal flap is elevated at the fascial level toward the costal margins and xiphoid. As the flap is elevated, segmental perforators from the epigastric arcade are identified and divided with hemoclips or electrocautery. We use Xylocaine with epinephrine along the incisions to decrease the amount of blood loss. Some surgeons will tumesce the upper abdominal flap with a dilute solution of Xylocaine with epinephrine. If this is done, the use of the electrocautery is less effective because of the fluid in the tissues.

According to preoperative markings, the abdominal flap is elevated and brought down to the intended lower incision to ensure that it is at a satisfactory level to allow for closure of the abdominal wound. Although some surgeons feel that traction of the abdominal flap will lower the inframammary fold, we have not found this to be the case.

The lower incision is then made all the way across the abdomen and deepened through scarpa’s fascia, dividing the superficial epigastric vessels and proceeding down to the anterior rectus sheath and the external oblique aponeurosis.

The flap is designed with the intention of using the ipsilateral hemiabdomen. This has the advantages of a shorter rotation and avoids the bulge over the epigastrium as long as the tunnel to pass the flap is made along the midline. The inframammary fold should not be completely released as this serves the most helpful guiding role throughout the reconstruction. The abdominal flap is elevated from lateral toward the midline.

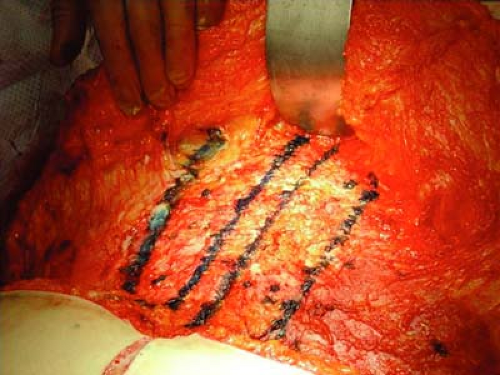

Figure 28.5 The medial and lateral fascial incisions have been made. The rectus muscle will be separated bluntly from the posterior sheath. |

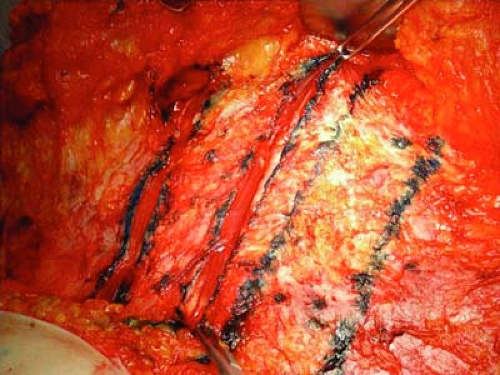

Please refer to Figures 28.5 through 28.9 for the following discussion. Fascial incisions cephalad to the abdominal flap are then made to dissect free the rectus abdominis pedicle. It is essential to maintain a 4- to 5-cm segment of the anterior rectus sheath, extending from just inside the midline to a point just lateral to the emergence of the epigastric perforators. This has two advantages.

It will help in calculating how much fascia to save at the level of the abdominal flap, which will include and maintain the perforator supplying the flap.

It avoids the need to dissect the fascia off the intersectiones tendineae, which is usually a bloody procedure.

The lateral aspect of the fascial incision, which was saved over the rectus muscle and maintains the perforators, has previously been identified and is continued in a caudal direction toward the pubis.

If a bilateral reconstruction is being performed, the flap may be divided in the midline from the umbilicus down to the pubis. The fascia may also be divided, saving at least 1 cm on each side of the midline.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree