Autologous Reconstruction: Latissimus Dorsi Flap

Justin M. Sacks

Steven J. Kronowitz

The goal of breast reconstruction is to recreate a normal-appearing breast with appropriate contour and volume. In addition, balancing inframammary folds and concealing scars is critical to any breast reconstruction. The breast mound that is created must be one that aesthetically matches that of the opposite breast in terms of shape, size, and volume. With these ideals in mind, the field of breast reconstruction has advanced through the optimization and use of both autologous and prosthetic devices.

Breast reconstruction can be performed with autologous tissue, implants, or a combination of both. Autologous tissue from the abdomen such as the transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous (TRAM) flap and its derivatives—the muscle-sparing TRAM (msTRAM), deep inferior epigastric perforator artery flap, and the superficial inferior epigastric artery flap—are all surgical options for achieving excellent aesthetic reconstructions. In addition, autologous tissues from the buttocks using the superior and inferior gluteal artery perforator flaps along with the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap (LDMF) and latissimus dorsi (LD) muscle flap allow reconstructive surgeons the ability to reconstruct the breast following both complete and partial mastectomy. Prosthetic devices such as tissue expanders (TEs), postoperative adjustable implants, and permanent implants alone or in combination with autologous tissue constructs allow the reconstructive surgeon the ability to construct a breast that appears almost equal to that of the normal opposite breast, or in the case of bilateral reconstructions, to create symmetrically appearing breasts. Although there are many different ways to attain an aesthetically pleasing and natural breast reconstruction utilizing autologous tissue, prosthetic devices, or a combination of both, there are no true “gold” standards. Each patient requiring breast reconstruction represents a unique reconstructive candidate with requirements that can often be satisfied with several options.

The pedicled LD muscle flap was one of the first autologous tissue constructs used for breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Originally described and popularized by Tansini in Europe during the early 1900s, it eventually fell out of use and did not regain

its popularity until the 1970s as the main flap for the reconstruction of radical mastectomy defects. With the advent of more conservative oncological approaches to breast surgery followed by immediate and delayed reconstruction using autologous tissue, specifically the TRAM flap as described by Hartrampf in 1976, the popularity of this flap has waxed and waned. The pendulum has once again shifted as newer breast implants have been created that allow the LDMF to be used in combination with these prosthetic devices for patients who require additional volume and who do not have or are not willing to spare the abdominal wall or buttock donor tissue.

its popularity until the 1970s as the main flap for the reconstruction of radical mastectomy defects. With the advent of more conservative oncological approaches to breast surgery followed by immediate and delayed reconstruction using autologous tissue, specifically the TRAM flap as described by Hartrampf in 1976, the popularity of this flap has waxed and waned. The pendulum has once again shifted as newer breast implants have been created that allow the LDMF to be used in combination with these prosthetic devices for patients who require additional volume and who do not have or are not willing to spare the abdominal wall or buttock donor tissue.

Breast reconstruction with TE alone and permanent implants is often suboptimal for patients undergoing mastectomies due to a paucity of soft tissue along with a restricted skin envelope on the chest wall. Invariably these women do not have the appropriate soft tissue alone using only the pectoralis major muscle flap along with their mastectomy flaps to appropriately cover the implant. For these women, the LDMF allows additional soft tissue coverage of the prosthetic devices to create natural breast contours and volume. Recapitulating the skin envelope and ptosis of the natural breast is the key to producing excellent results. The LDMF allows the native skin to be expanded immediately allowing, at times, a permanent implant to be placed submuscularly. Furthermore, the ability to harvest the LDMF with added subcutaneous tissue or fat in an extended form allows immediate and delayed breast reconstruction to occur for women who have chosen this type of reconstruction with or without prosthetic breast implants.

Use of the LDMF in breast reconstruction offers the ability to create a natural-appearing breast for both partial and complete mastectomy defects. The soft tissue of the LDMF, which includes skin, adipose tissue, fascia, and muscle, can be utilized to fill in the contours for partial mastectomy defects with or without the use of prosthetic devices. The use of a skin island centered over the LD muscle, taking advantage of its musculocutaneous perforators, allows the breast to be reconstructed in an immediate or delayed fashion. This skin island, with its thick dermis from the back, can also be used for nipple areola reconstruction in an immediate or delayed fashion.

There are several indications for the use of the LDMF in breast reconstruction. However, since there are other excellent choices for breast reconstruction, it is important to clearly define what we feel are the optimal indications for the use of the LDMF. The LDMF still remains a distant option for most breast reconstructive surgeons secondary to the need for simultaneous implant insertion along with donor site morbidity in terms of aesthetic and sometimes functional deficits. With the advent of newer and more anatomically shaped prosthetic devices, there has been resurgence in the use of the LDMF combined with prosthetic implant devices, which in many cases may allow comparable reconstructions to that of either autologous tissue or prosthetic reconstruction alone.

Indications for the use of a LDMF in partial or complete breast reconstruction include the following:

Mastectomy flaps not sufficient to provide appropriate contour and shaping of the reconstructed breast with TEs alone, and the patient defers the use of autologous tissue from the abdomen.

Mastectomy flaps not sufficient to provide appropriate contour and shaping of the reconstructed breast with TEs alone and the abdominal donor site is not appropriate for use. These patients who are often thin and do not have available abdominal wall tissue. In addition, these patients may have abdominal scars such as transverse subcostal incisions or midline longitudinal incisions, which preclude the appropriate use of the abdominal wall tissue.

Obese patients with TE and permanent implants alone will not have the appropriate breast projection. In addition, in this patient population, harvest of the LDMF is often safer with respect to donor site morbidity of using the abdominal wall where wound dehiscence, seroma, infection, bulge, and hernia rates are more common.

Partial mastectomy defects that require soft tissue volume replacement. The nipple–areola complex (NAC) is often in a nonanatomical position secondary to scar and radiation fibrosis. In addition, if it is known that a patient will have a significant soft tissue loss from a partial mastectomy defect, it is helpful to fill the dead space with the LD muscle with or without a skin paddle.

Poland syndrome is a congenital disorder affecting the chest wall and the ipsilateral upper extremity. The LDMF can be used to reconstruct the missing pectoralis major muscle and redefine the anterior axillary line, infraclavicular area, and breast area. Prosthetic devices can be used at the initial time of surgery or in a delayed fashion to augment volume deficits.

The LD muscle can be used to augment the superior pole in women who have undergone autologous tissue reconstruction using TRAM flaps or their derivatives. In these women, there is a paucity of superior pole fullness, and the LD muscle allows the soft tissue deficiency to be corrected.

Women who have thin skin overlying a potential TE reconstruction. The LD muscle is placed caudally to the pectoralis major muscle and sutured to the lower mastectomy flap just above the inframammary fold. This provides contour and coverage for the TE and ultimate permanent implant.

Women who have excess or redundant lateral back tissue and who are not candidates for abdominal autologous tissue.

Patients who request the use of autologous tissue but are not willing to undergo the extended recovery time of a TRAM-type reconstruction from the abdomen. These are patients who want to return to normal activities of daily living sooner and are not willing to undergo the potential for a prolonged recovery, which is often the case in breast reconstructions using the abdominal wall.

Contraindications

The LDMF is contraindicated in women who have large skin requirements for immediate or delayed breast reconstruction. In these situations, abdominal wall tissue is preferred. The LDMF can be used for chest wall coverage in cases of inflammatory breast cancer in which the mastectomy flaps are unable to be closed, and the patient will receive adjuvant radiotherapy. However, in standard breast reconstruction, this flap should not be used if the skin requirements are greater than the proposed dimensions of the LD skin paddle.

The LDMF is relatively contraindicated in patients who have previously undergone axillary lymph node dissections followed by radiation therapy. It can be extremely difficult to perform an appropriate dissection of the neurovascular pedicle in these situations. Vascular injury or insufficiency can result from a previously dissected axilla. There are certain situations when it is known that the thoracodorsal pedicle has been previously transected. Although the LDMF can potentially be harvested on the serratus branch, this has been shown to result in an increased incidence of flap necrosis.

Additional relative contraindications to using the LDMF are patients who have undergone posterior thoracotomies where the LD muscle has been transected. In addition, patients who have a known preexisting shoulder dysfunction or athletes who require the use of this muscle should not be considered candidates for this pedicle transfer.

In order for the LDMF to be utilized for breast reconstruction, certain patients must be willing to undergo the insertion of a prosthetic device. The volume of the standard LDMF is most often not sufficient to create an appropriate reconstructed breast. The extended LDMF can be considered to replicate the shape and volume; however, donor site seromas are higher in the flap technique. Patients must be clearly advised of this.

Anatomy and Function

The LD muscle is responsible for extension, adduction, and internal rotation of the shoulder joint. It also plays a role in assisting with extension and lateral flexion of the lumbar spine. The LD muscle has a type V Mathes and Nahai vascular supply classification, meaning it has a dominant blood supply from the thoracodorsal artery and vein, a branch of the subscapular vessels, and secondary blood supply belonging to perforators

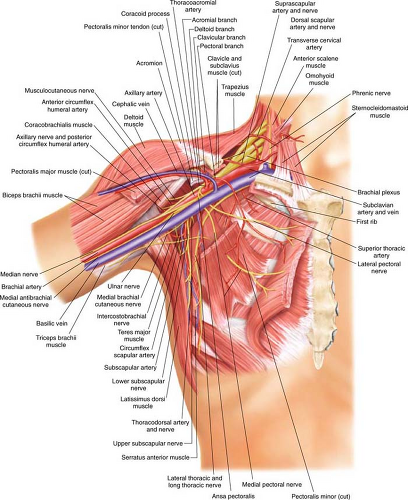

from the posterior paraspinal system. The axillary vessels give rise to the subscapular vessels that give rise to the thoracodorsal vessels (Fig. 30.1). The serratus branch splits from the thoracodorsal vessels as it enters the LD muscle. The thoracodorsal pedicle enters the deep surface of the LD muscle approximately 10 cm below the axillary vessels and 2 to 3 cm inside the lateral edge of the this muscle. This vessel then splits into two terminal vessels within the LD muscle. By taking advantage of this vascular pattern, the LD muscle can be harvested separately on these branches to potentially limit the use of the muscle and move these segments independently, especially when a skin paddle is not required. Several musculocutaneous perforators supply the skin paddle, which is usually centered over the muscle. As long as the skin paddle is centered over the muscle, there is typically no concern that it will not capture a musculocutaneous perforator and have an adequate blood supply.

from the posterior paraspinal system. The axillary vessels give rise to the subscapular vessels that give rise to the thoracodorsal vessels (Fig. 30.1). The serratus branch splits from the thoracodorsal vessels as it enters the LD muscle. The thoracodorsal pedicle enters the deep surface of the LD muscle approximately 10 cm below the axillary vessels and 2 to 3 cm inside the lateral edge of the this muscle. This vessel then splits into two terminal vessels within the LD muscle. By taking advantage of this vascular pattern, the LD muscle can be harvested separately on these branches to potentially limit the use of the muscle and move these segments independently, especially when a skin paddle is not required. Several musculocutaneous perforators supply the skin paddle, which is usually centered over the muscle. As long as the skin paddle is centered over the muscle, there is typically no concern that it will not capture a musculocutaneous perforator and have an adequate blood supply.

Nerve supply to the LD muscle is the thoracodorsal nerve. The nerve is a branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, deriving its fibers from C6, C7, and C8. The nerve follows the course of the subscapular artery where it can be traced along the lower border of the muscle. The nerve is typically found in a medial position relative to the vascular bundle. The nerve is typically transected to prevent postoperative contraction of the muscle. Some surgeons do not transect the nerve because of concern that

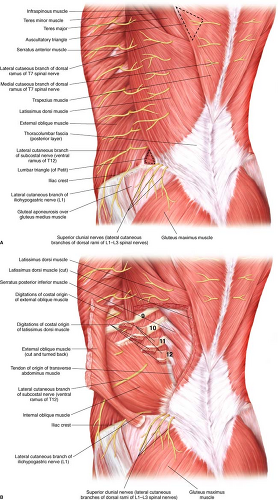

the muscle will atrophy and the resultant effect of transferring the muscle to the chest wall or mastectomy site will be ameliorated. We prefer transaction of both the insertion (floor of intertubercular groove of the humerus) and its origin (spinous processes of thoracic T7–T12, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, and inferior three or four ribs) but sparing the nerve creates a clinical situation that does not lead to postoperative muscle contraction and does not cause significant atrophy (Fig. 30.2).

the muscle will atrophy and the resultant effect of transferring the muscle to the chest wall or mastectomy site will be ameliorated. We prefer transaction of both the insertion (floor of intertubercular groove of the humerus) and its origin (spinous processes of thoracic T7–T12, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, and inferior three or four ribs) but sparing the nerve creates a clinical situation that does not lead to postoperative muscle contraction and does not cause significant atrophy (Fig. 30.2).

Clinical Assessment

Determining the status of the thoracodorsal pedicle to the LD muscle must be confirmed prior to surgery. Information can be readily attained by reading prior operative notes if the patient has previously undergone an axillary lymph node dissection. The status of the pedicle is typically discussed, and this information can often be useful. However, there is no substitute for clinical evaluation. In the preoperative setting, patients are asked to place their hands at their sides and push inward. If the patient has a denervated LD, the scapula will pull upward and outward, appearing almost “winged.” This is secondary to the anatomical orientation of the LD in how it drapes across the tip of the scapula, keeping it fixed to the chest wall. In addition, having patients abduct their arm and push against resistance while the LD muscle is palpated can reveal functional status. If there

has been a history of a prior axillary lymph node dissection, it is critical to consider that the pedicle to the LD flap has been compromised. If this is the case, the vascular branch to the serratus muscle can be used in a retrograde fashion for blood supply to the muscle. However, in this situation, there are reported incidences of flap necrosis when the LDMF is solely based on the serratus pedicle. It is, therefore, critical that the LD muscle be assessed intraoperatively. If there is evidence of atrophy, then the neurovascular pedicle was most probably compromised during the lymph node dissection or has intimal damage from radiotherapy. In this instance, even though it can be harvested on the serratus anterior branch, the volume of the LD muscle and integrity of the skin paddle can be affected. Another autologous flap would be recommended in this situation.

has been a history of a prior axillary lymph node dissection, it is critical to consider that the pedicle to the LD flap has been compromised. If this is the case, the vascular branch to the serratus muscle can be used in a retrograde fashion for blood supply to the muscle. However, in this situation, there are reported incidences of flap necrosis when the LDMF is solely based on the serratus pedicle. It is, therefore, critical that the LD muscle be assessed intraoperatively. If there is evidence of atrophy, then the neurovascular pedicle was most probably compromised during the lymph node dissection or has intimal damage from radiotherapy. In this instance, even though it can be harvested on the serratus anterior branch, the volume of the LD muscle and integrity of the skin paddle can be affected. Another autologous flap would be recommended in this situation.

Marking

The patient is marked in a well-lit room in the standing position at both the recipient (mastectomy) and the donor (LDMF) sites. First, the breast markings are made, which include the sternal notch, midline, bilateral inframammary folds, and the superior borders of the breast. In the operating room, the inframammary folds are reinforced with a sterile marker as often these marks become faded following surgical preparations or from the mastectomy procedure.

The patient’s back and lateral chest wall is marked to delineate the LD muscle, the skin paddle used for breast reconstruction and the pathway for which the LDMF will be placed under the axilla and into the partial or complete mastectomy defect (Fig. 30.3 A and B).

First, the tip of the scapula is marked, along with the iliac crest and the posterior midline. These are critical marks and should be performed only in the standing position to allow proper delineation of anatomical landmarks. It is helpful to have the patient abduct and adduct the shoulder complex to appropriately confirm the tip of the scapula. In obese patients, it is often difficult to palpate this key anatomical landmark. If this landmark is not established, the potential for inappropriately setting the skin paddle on the LD muscle becomes greater. Next, the anterior lateral and inferior borders of the LD muscle are marked. Having patients adduct their arm against resistance to feel the anterolateral edge of the LD muscle is extremely helpful when marking this border. The upper border of the muscle is marked as it extends from the axilla across the tip of the scapula. The trapezius muscle is then marked as it overlaps the upper medial portion of the LD muscle. This marking is meant to be a reminder during surgical dissection of this critical landmark. Often times, the trapezius muscle can be elevated inadvertently during the LD muscle harvest, and this anatomical boundary should not be violated.

First, the tip of the scapula is marked, along with the iliac crest and the posterior midline. These are critical marks and should be performed only in the standing position to allow proper delineation of anatomical landmarks. It is helpful to have the patient abduct and adduct the shoulder complex to appropriately confirm the tip of the scapula. In obese patients, it is often difficult to palpate this key anatomical landmark. If this landmark is not established, the potential for inappropriately setting the skin paddle on the LD muscle becomes greater. Next, the anterior lateral and inferior borders of the LD muscle are marked. Having patients adduct their arm against resistance to feel the anterolateral edge of the LD muscle is extremely helpful when marking this border. The upper border of the muscle is marked as it extends from the axilla across the tip of the scapula. The trapezius muscle is then marked as it overlaps the upper medial portion of the LD muscle. This marking is meant to be a reminder during surgical dissection of this critical landmark. Often times, the trapezius muscle can be elevated inadvertently during the LD muscle harvest, and this anatomical boundary should not be violated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree