Chapter 8 Arthrosis Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear and Reconstruction

Pathophysiology of Osteoarthritis Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Previous studies have shown that restoring knee stability through ACL reconstruction does not necessarily decrease the incidence of posttraumatic OA.1,2 It therefore follows that other mechanisms, rather than the initial mechanical disturbance of stability at the time of injury, may be responsible for the development of OA, both in the chronic ACL deficient knee and in the reconstructed knee.

Several biochemical mechanisms have been proposed. It has been shown that an early increase in the proteoglycan content of articular cartilage adjacent to the torn ligament occurs following ACL rupture.3 Other studies4,5 have shown an increase in collagenase activity leading to increased denaturation and loss of type II collagen in the articular cartilage of the knee following injury. These changes are also seen in the knee with idiopathic OA.

Intraarticular pro-inflammatory cytokines are also increased immediately after ACL rupture.6,7 These include interleukins (IL) -1, -6, and -8, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and keratan sulfate. Of note, IL-1 (in both its alpha and beta forms) and TNF-α have direct chondrodestructive effects independent of their inflammatory properties. These cytokines are present in higher concentrations with more severe chondral damage, and levels fall gradually beginning approximately 3 months postinjury. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) concentrations are initially normal but become grossly elevated beginning approximately 3 months postinjury. Conversely, the chondroprotective cytokine IL-1Ra concentration decreases with increasing severity of chondral damage and with chronic ACL deficiency.

It has been shown that ligamentous knee injury is strongly associated with bone bruising.8 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans performed acutely following ACL rupture have shown occult subchondral lesions in 85% of patients, mainly involving the lateral femoral condyle and lateral tibial plateau.9 Although the majority of these lesions resolved with time, permanent chondral damage is known to have occurred in some lesions. Histological analysis of these bone bruises has shown associated areas of chondrocyte degeneration and necrotic osteocytes, which suggests that significant damage to the articular cartilage is sustained at the time of injury.10

Following ACL reconstruction, further factors may play an additional role in the development of arthrosis. It has been shown that pretensioning the graft can cause changes in joint biomechanics that may lead to arthrosis in the long term.11,12 Shortening of the patellar tendon may occur after patellar tendon autograft, which has been shown to lead to patellofemoral arthrosis and a worse functional outcome, both of which are directly associated with the degree of shortening of the patellar tendon.13

Any intraarticular damage that requires treatment with meniscectomy will diminish the joint contact surface area and increase the stress on the tibia.14 The resultant increased stress on the knee joint has been shown to accelerate the development of OA.15

Natural History of the Untreated Anterior Cruciate Ligament Deficient Knee

The development of arthrosis following ACL rupture is widely recognized,16,17 and in a review by Gillquist and Messner18 it was concluded that in the long term (i.e., 10 to 20 years), as many as 70% of all ACL deficient knees had radiological signs of arthrosis, although clinical symptoms of knee arthritis were infrequent. Segawa et al19 found radiographic changes of OA in 63% of patients who were followed for 12 years after a conservatively treated ACL rupture. The main risk factor for arthrosis was shown to be meniscectomy, in combination with the risk factors for primary OA, such as increased age at time of injury, increased level of sports activity, obesity, and OA of the contralateral knee.

In a study of patients with symptomatic knee OA, 22.8% had complete ACL rupture identified at MRI, compared with 2.7% of controls.20 Patients with OA in the presence of an ACL rupture had more severe radiological OA.

A cohort of female soccer players in Sweden was assessed 12 years after a known ACL injury, and although radiographic evidence of OA was seen in 82%, there was no difference in the incidence of OA between those ACL injuries treated nonoperatively (38%) and those treated with reconstruction, and the same proportion (75%) of those without radiographic OA had knee symptoms.2 Comparable results were seen in a similar study of male soccer players in Sweden 14 years following a known ACL injury.21

In children and adolescents with ACL rupture, nonoperative treatment is often favored to avoid drilling surgical tunnels across physeal growth plates. However, it has been shown that ACL injuries treated nonoperatively in this age group are likely to develop instability and poor function, with development of radiological signs of degeneration in almost half of children.22 Subsequent studies have shown that ACL reconstruction can be safely undertaken in adolescents nearing skeletal maturity.23 It has not yet been proven that this can be safely performed in very young children with opened physes.

Despite this evidence, some studies challenge the concept that ACL tears are inextricably linked to development of arthritis. It has been shown that in older patients (40 to 60 years old) with an ACL rupture treated nonoperatively, 87% had little or no radiographic changes at a mean of 7 years postinjury.24 In 46 young recreational athletes followed up at an average of 5 years following conservative treatment of an ACL tear diagnosed at arthroscopy, only 17.4% had mild radiographic osteoarthritic changes, and only one patient (2.2%) was symptomatic.25

Arthrosis Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

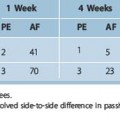

With the knowledge that ACL tears are associated with an increased risk of OA, it would seem reasonable to assume that ACL reconstruction would play a useful role in prevention of arthrosis in the long term. The difficulties in implementing large long-term follow-up studies following ACL reconstruction have already been mentioned. Table 8-1 summarizes the recent literature that has evaluated the incidence of arthrosis following ACL reconstruction. Analysis of these studies clearly suggests that surgical reconstruction of the ligament does not prevent the development of radiological OA. A meta-analysis by Lohmander and Roos26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree