Introduction

Safe and effective reconstructive surgical procedures rely on a clear knowledge of facial and neck arterial anatomy. Cadaveric angiographic and dissection studies have demonstrated that the external and internal carotids are the main arterial sources for the head and neck regions.

The skin and soft tissue of the face receive their arterial supply from the branches of the facial, maxillary, and superficial temporal arteries, all of which are branches of the external carotid. The exception is a masklike area that includes the central forehead, the eyelids, and the upper part of the nose and is supplied via the internal carotid artery system via the ophthalmic arteries. The ophthalmic artery gives off branches to the face, including the lacrimal, supraorbital, supratrochlear, dorsal nasal, and external nasal arteries.

Because there are communications between the external and internal carotid artery systems around the eye, external nose, and forehead through several anastomoses, knowledge of the arterial territories is important in flap anatomy. Most flaps are based on vascularization of the arteries, and anatomical variations must be considered when individual flaps are planned for patients. To elevate an arterial flap safely, routine use of a Doppler probe preoperatively and intraoperatively is recommended.

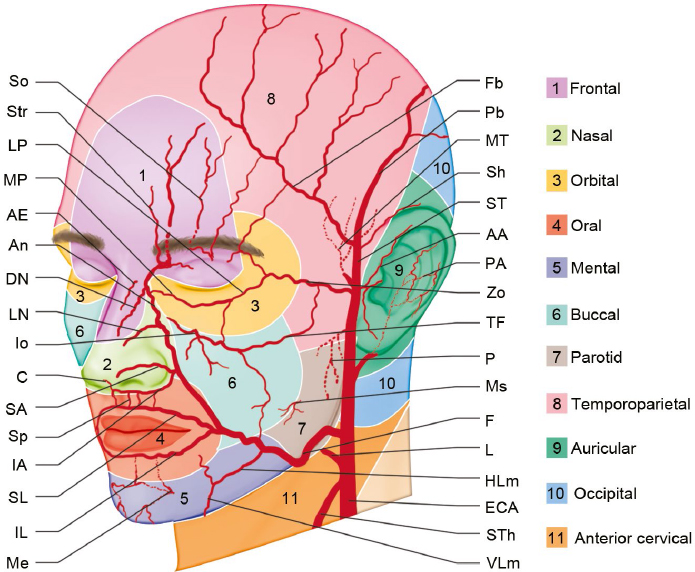

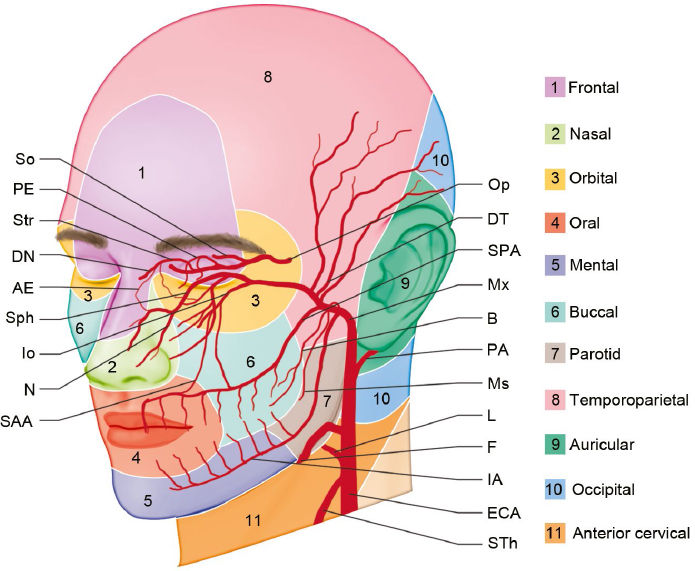

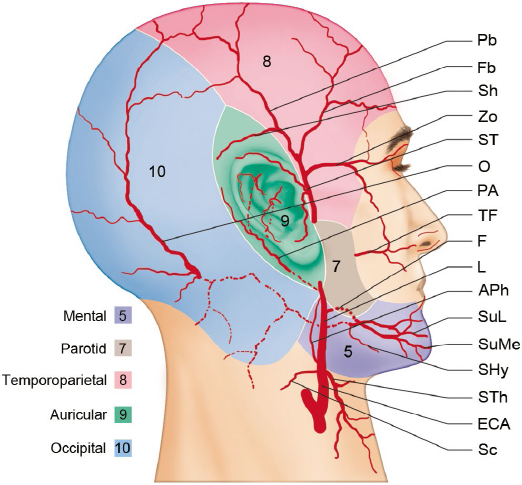

The primary arterial territories of the head and the neck have been defined by mapping their three-dimensional territories in the skin, the deep soft tissues, and the bones.1–3 The external carotid artery supplies the exterior of the head, the face, and much of the neck. The internal carotid artery supplies the central face, which contains the eyes, the upper two-thirds of the nose, and the central forehead4 (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.2, Fig. 6.3).

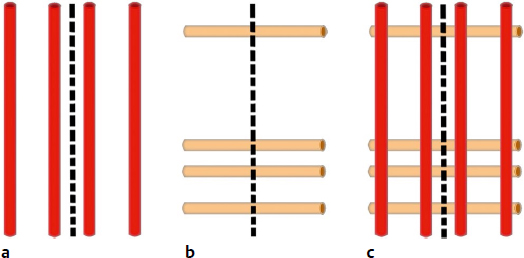

There is a rich anastomotic network between the branches of the internal carotid and ophthalmic artery systems (supraorbital or supratrochlear vessels) (Fig. 6.4a) and the angular artery and superficial temporal artery via the transverse facial artery to the facial artery (Fig. 6.4b). There are also multiple anastomoses between the facial and maxillary artery territories via the infraorbital and mental arteries (Fig. 6.4c).3,5

Reconstruction methods for facial defects include skin grafts, local flaps, pedicled flaps, and microvascular tissue transfers6; however, remote tissues do not provide ideal tissue contour, thickness, texture, or shape for the facial structures; hence, they often require multiple revisions and result in donor-site morbidity.1,7 Muscles and other tissues have a vital role because they provide anastomotic networks for preventing vascular compromise.

The many changes undergone by embryonic arteries, such as regression or reappearance, can result in variations of the origin points, the courses, and the anastomotic features of the vessels. Arterial variations can be explained by the persistence of channels that normally disappear or by the disappearance of normally persisting vessels. These anatomical variations arising from embryologic development can be significant.8,9 Doppler ultrasound helps to define arterial features and provides information about backflow and the potential for reverse flow in the artery.7,10

External Carotid Artery

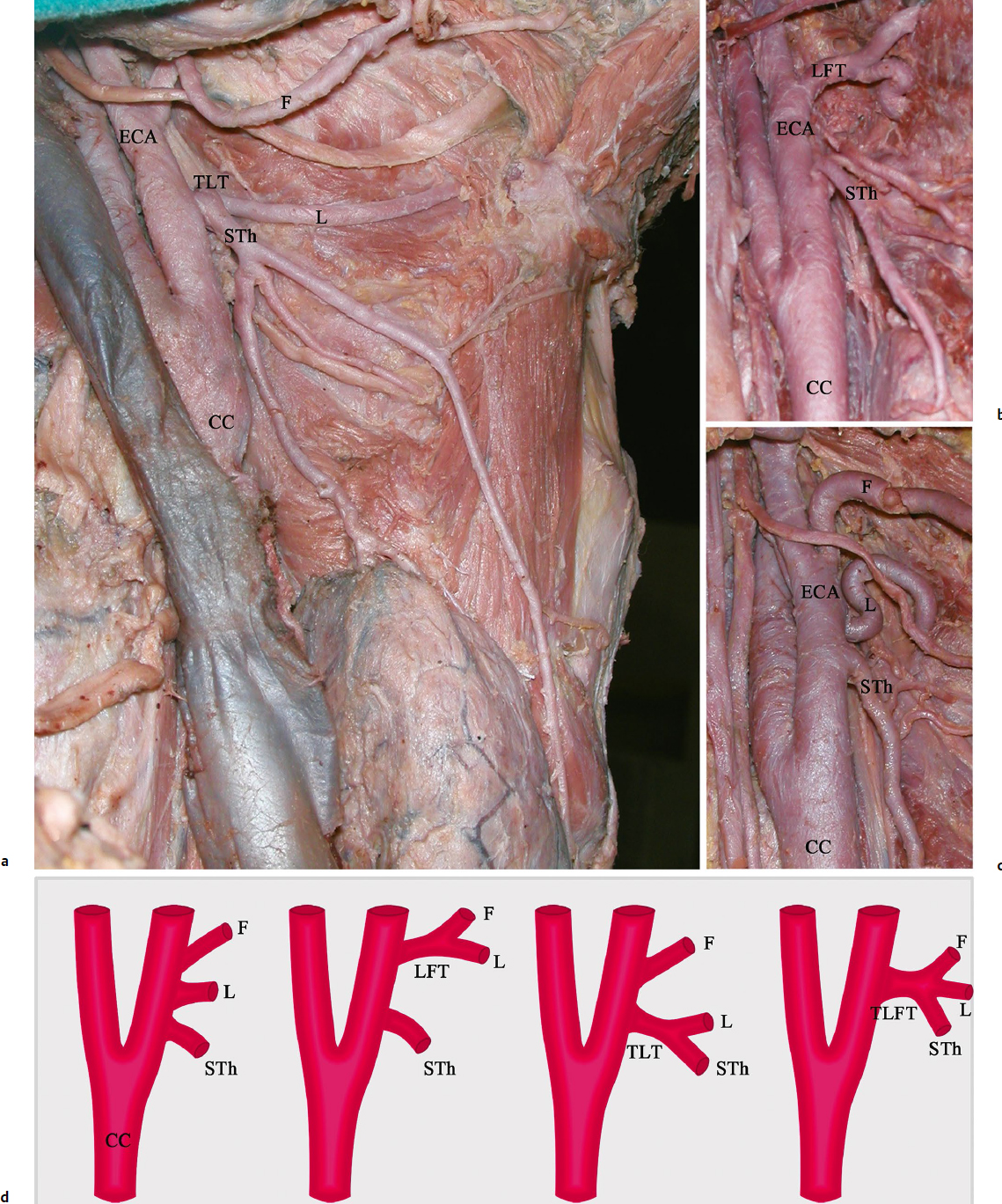

The cervical part of the common carotid is usually divided into the external and the internal carotid arteries at the level of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage. The carotid bifurcation is located 13.2 ± 5.6 mm below the tip of the greater horn of the hyoid bone. The external carotid artery is covered by skin, superficial fascia, platysma, deep fascia, and the anterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It begins by taking a slightly curved course and then passes upward and forward.11 After branching on its anterior (superior thyroid, lingual, facial arteries) and posterior (ascending pharyngeal, occipital, posterior auricular arteries) sides, the artery inclines backward to the space behind the neck of the mandible, where it is divided into its terminal branches, the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.2).

Fig. 6.2 The deep arteries of the head and neck regions in anterolateral oblique view. Regions: arterial territories: (1) frontal: Str, So, MP (O territory); (2) nasal: DN, AE, An (F-O territory); (3) orbital: MP, LP, Io (O-Max-Zo territory); (4) oral: SL, IL (F territory); (5) mental: Me, IL (Max-F territory); (6) buccal: Io, TF (Mx-ST territory); (7) parotid: TF, Ms (ST territory); (8) temporoparietal: Fb, Pb, MT (ST territory); (9) auricular: AA, PA (ST-ECA territory); (10) occipital: O (ECA territory); (11) anterior cervical: STh (ECA territory). AE, anterior ethmoidal artery; B, buccal artery; DN, dorsal nasal artery; DT, deep temporal artery; ECA, external carotid artery; F, facial artery; IA, inferior alveolar artery; Io, infraorbital artery; L, lingual artery; Ms, masseteric artery; Mx, maxillary artery; N, nasopalatine artery; PA, posterior auricular artery; PE, posterior ethmoidal artery; Op, ophthalmic artery; SAA, superior alveolar artery; SPA, superior posterior alveolar artery; Sph, sphenopalatine artery; So, supraorbital artery; Str, supratrochlear artery; STh, superior thyroid artery.

Fig. 6.4 Schematic representation of the arterial anastomoses in three patterns. (a) Intercarotid anastomoses (angular and dorsal arteries). (b) Transfacial anastomoses (radix, lateral nasal, marginal, and subnasal arteries). (c) Polygonal system (intercarotid and transfacial). Red: intercarotid; orange: transfacial interconnected arteries.

Surgical Annotation

The superior thyroid, lingual, and facial arteries originate as separate branches in 50 to 80%; a lingulofacial trunk exists in 18 to 31%, a thyrolingual trunk in 1 to 18%, and a thyrolingulofacial trunk in about 2.5% (Fig. 6.5).8,9,11,12 The carotid bifurcation is commonly located at the superior border of the thyroid cartilage. The distance from the origin of the superior thyroid artery to the carotid bifurcation is 3.3 ± 4.3 mm, from the origin of the superior thyroid artery to that of the lingual artery is 10.5 ± 5.2 mm, and from the origin of the superior thyroid artery to that of the facial artery is 18.2 ± 8.8 mm.8,9,12

Superior Thyroid Artery

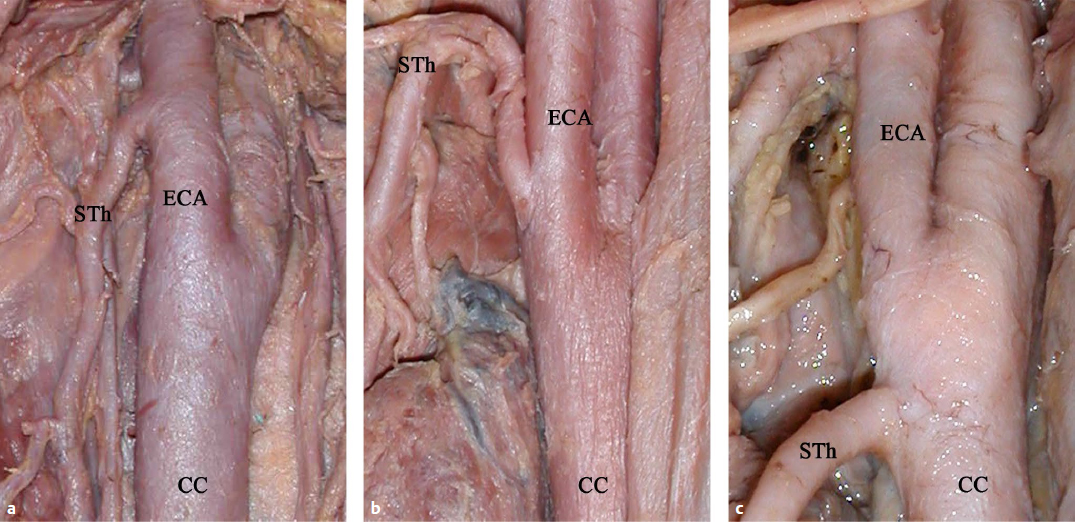

The superior thyroid artery typically arises from the anterior surface of the external carotid just below the level of the greater cornu of the hyoid bone, although there are variations (Fig. 6.6).8,9,11,12 The superior thyroid artery usually has a sharp downward angle at its origin. From its origin under the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, it runs upward and forward for a short distance in the carotid triangle; it then arches downward beneath the infrahyoid muscles (Fig. 6.5a). It distributes twigs to the adjacent muscles and numerous branches to the thyroid gland, anastomosing with its fellow on the opposite side and with the inferior thyroid arteries.

Surgical Annotation

The origin of the superior thyroid artery can be identified 13 ± 4.5 mm below the tip of the greater horn of the hyoid. The distance from its origin to the thyroid cartilage’s upper edge is 7.1 ± 6.4 mm and to the horizontal plane passing through the upper edge of the thyroid gland is 26.1 ± 12.1 mm.8,9,12

Lingual Artery

The lingual artery arises from the external carotid artery between the origin of the superior thyroid and facial arteries. It first runs obliquely upward and medially to the greater cornu of the hyoid bone (Fig. 6.5). It then curves downward and forward and passes beneath the digastric and stylohyoid muscles. It runs horizontally forward, beneath the hyoglossus muscle, finally ascending as the deep lingual artery.

Surgical Annotation

The branching patterns can vary. These anatomical variations arise from embryological development and can be significant in clinical cases (Fig. 6.5, Fig. 6.6). The anatomical characteristics and variations of the external carotid, superior thyroid, lingual, and facial arteries, such as their branching patterns, lengths, and outer diameters, are crucial for safe implementation of intra-arterial catheterization for administering anticancer drugs to the head and the neck, surgical excision of benign and malignant tumors, and microsurgical arterial implantations.8,9,12

The distance from the origin of the lingual artery to the carotid bifurcation is 12 ± 5.9 mm, to the origin of the facial artery is 5.3 ± 5.2 mm, and to the thyroid cartilage’s upper edge is 15.6 ± 7.7 mm.

Occipital Artery

The occipital artery arises from the external carotid (89–95%) or as a common trunk with the posterior auricular artery from the external carotid artery (5–10%). From the mandibular angle, the origin of the occipital artery is on average 13.4 mm (5–22 mm) above in 29% cases, 17.6 mm (4–32 mm) below in 57%, and at the same level in 14%. From the external carotid artery, the artery emerges from the posterior side in 88%, from the lateral side in 8%, and from the medial side in 4%. It takes a tortuous course superiorly and posteriorly toward the base of the scalp, traveling beneath the splenius capitis and the sternocleidomastoid muscles.11,13,14 The mean length of the artery is 9 cm (3.4–12.5 cm). It is divided into descending, horizontal, and vertical branches (Fig. 6.3). The horizontal branch runs along the nuchal ridge, connecting across the midline to branches of the contralateral occipital artery. The vertical branch runs superiorly along the posterior skull and anastomoses with the posterior auricular, superficial temporal, and supraorbital arteries (Fig. 6.7c,d). The descending branch is divided over the trapezius, and it supplies the trapezius, splenius, and sternocleidomastoid muscles. The descending branch anastomoses with the deep cervical and the ascending branch of the transverse cervical arteries.2,15

The sternocleidomastoid artery generally arises from the occipital artery, but sometimes it springs directly as a separate branch from the external carotid artery (Fig. 6.3). The distance from the origin of the sternocleidomastoid branch to the external carotid artery is 14.4 mm. It passes downward and backward over the hypoglossal nerve and supplies the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the integument.11

Surgical Annotation

The occipital artery is the main artery of the suboccipital region. The vascular network of the cervico-occipital flap consists of the cutaneous and musculocutaneous perforators of the descending branch of the occipital artery anastomosing with the cervical arteries and the cutaneous branches of spinal arteries in the region around the nape of the neck. The cervico-occipital flap is used to reconstruct defects after resection of the mandible or the floor of the mouth and the tongue or to close pharyngoesophageal and tracheal fistulae. As the content of the cervico-occipital flap is richly vascularized and as the two-headed sternocleidomastiod muscle has minimal donor-site morbidity, it is preferred as a myocutaneous flap for stable and durable reconstruction. The upper third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is supplied by branches of the occipital artery. The middle third receives a branch from the superior thyroid artery (42%), the external carotid artery (23%), or both (27%). The lower third is supplied by a branch arising from the suprascapular artery.2,15 In the suboccipital region, the mean distance between the point at which the occipital artery pierces the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the inion is 4.8 cm (3.9–6.5 cm). The mean distance between the piercing point of the artery in the muscle and the lower part the mastoid process is 5.1 cm (3.9–5.9 cm). Classically, the occipital artery enters the sternocleidomastoid muscle 1.5 to 2 cm below the anterior margin. The point where the occipital artery enters the sternocleidomastoid and then comes out to the surface up to 4 cm under the process is determined as the reference point. Studies suggest that the greater occipital nerve crosses the occipital artery lateral to the inion. Occipital artery biopsy should be performed between 4 to 5 cm lateral and 1 to 3 cm proximal to the inion to avoid injury to this artery in vasculitis cases.2,4,15

Posterior Auricular Artery

The posterior auricular artery arises from the external carotid artery, above the digastric and stylohyoid muscles, opposite the apex of the styloid process.7,16,17 It has a mean distance of 0.29 cm anterior to the mastoid tip, just deep to the lobule and in the posterior auricular sulcus. It ascends, under cover of the parotid gland, on the styloid process of the temporal bone and, immediately above this point, divides into its auricular and occipital branches (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.2, Fig. 6.3, Fig. 6.7c,d). The occipital branch passes backward, over the sternocleidomastoid muscle, to the scalp above and behind the ear. It anastomoses with the occipital artery (Fig. 6.7c,d).

Fig. 6.7 Blood supply of the (a, b) forehead, (c) occipital, and (d) retroauricular regions. Red latex is injected into the common carotid arteries before dissection. Fb, frontal branch of the superficial temporal artery; LP, lateral palpebral artery; MP, medial palpebral artery; O, occipital artery; PA, posterior auricular artery; Pb, parietal branch of the superficial temporal artery; So, supraorbital artery; Str, supratrochlear artery; *, anastomoses.

Surgical Annotation

The arterial network in the upper ear is formed from the posterior auricular artery. The mean length of this artery before it penetrates the temporoparietal fascia measured from the mastoid tip is 75.6 mm. The posterior auricular artery gives off a retroauricular branch to the posterior surface of the auricle and an occipital branch to the postauricular skin, which travels in the postauricular sulcus. The mean distances from the mastoid tip is 8.4 mm to the occipital branch and 6.8 mm to the auricular branch. The arterial network of the triangular fossa and scaphoid fossa is provided by branches of the superficial temporal and posterior auricular arteries.

Facial Artery (External Maxillary Artery)

The facial artery arises at the level of the greater horn of the hyoid bone a little above the lingual artery’s origin from the external carotid. It can arise from various trunks from the external carotid (Fig. 6.5). Hence, the level of the origin is situated 19.6 ± 8.7 (10–35 mm) away from the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. The distance from the origin of the facial artery to a horizontal plane passing over the top side of the thyroid cartilage is 15.4 ± 8.4 mm. It ascends under cover of the posterior belly of the digastric and stylohyoid muscles and grooves the submandibular gland by making a loop. It curves upward over the body of the mandible at the antero inferior angle of the masseter muscle. It then passes forward and upward across the cheek to the labial commissure. The distances from the facial artery are 13.5 mm (8–23 mm) to the labial commissure and 45 mm (28–60 mm) to the midline. It then ascends along the side of the nose and ends at the medial commissure of the eye as the angular artery (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.8).

The course of the artery can vary.6,18–20 Branches to the face include the ascending palatine, inferior labial, tonsillar, superior labial, glandular, lateral nasal, submental, angular, and muscular arteries. The facial artery and its branches mainly supply the mental region, the lips, the inferior part of the parotidomasseteric region, and the buccal, orbital, infraorbital, and nasal regions (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.3).3–5,7,11

Submental Artery

The submental artery is usually the largest of the cervical branches (Fig. 6.3). The distances of the origin of the submental artery are 27.5 mm (19–41 mm) to that of the facial artery and 23.8 mm (1.5–39 mm) to the mandibular angle.2,21 The artery is deep to the anterior belly of the digastric muscle in 70–80%. It passes superficial to the mylohyoid nerve, 16.8 mm (9–34 mm) from its origin. A visible anastomosis between the two submental arteries is noted in 92%.20 It anastomoses with the sublingual artery and with the mylohyoid branch of the inferior alveolar artery; at the symphysis menti, it turns upward over the border of the mandible and then is divided into superficial and deep branches. The superficial branch passes between the integument and depressor labii inferioris and anastomoses with the inferior labial artery; the deep branch runs between the muscle and the bone, supplies the lip, and anastomoses with the inferior labial and mental arteries.20

Surgical Annotation

The axial myocutaneous platysma flap using the upper part of the mylohyoid muscle is supplied by the submental artery.2,21 Dissection of the pedicle back to the origin of the facial artery and vein to extend the arc of rotation of the flap is recommended. The diameter of the submental artery is suitable for safe microvascular transfer (1.7–2.2 mm).5,21 The length of the submental artery is 58.9 mm (35–108 mm); its length from the origin to the anterior belly of the digastric muscle is 31.5 mm (26–38 mm).21

The facial artery crosses the inferior border of the mandible obliquely to enter the face at the anteroinferior angle of the masseter muscle. The distance between the mandibular angle and the point where the facial artery crosses the lower border of the mandible is 26.6 mm (15.5–38 mm).21 It is extremely tortuous. It gives off small muscular branches to the masseter and the depressor anguli oris muscles (Fig. 6.8a).

Inferior Labial Artery

The inferior labial artery arises near the angle of the mouth; it passes upward and forward beneath the depressor anguli muscle or penetrates the orbicularis oris muscle (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.8a). The distance from the origin of the inferior labial artery from the labial commissure is 19.3 ± 10 mm (4–35 mm). It follows a tortuous course along the edge of the lower lip between the muscle and the mucous membrane. The length of the inferior labial artery is 34.5 ± 20.8 mm (29–67 mm).18,20,21 It supplies the labial glands, the mucous membrane, and the muscles of the lower lip. It anastomoses with the artery on the opposite side and with the mental branch of the inferior alveolar artery.

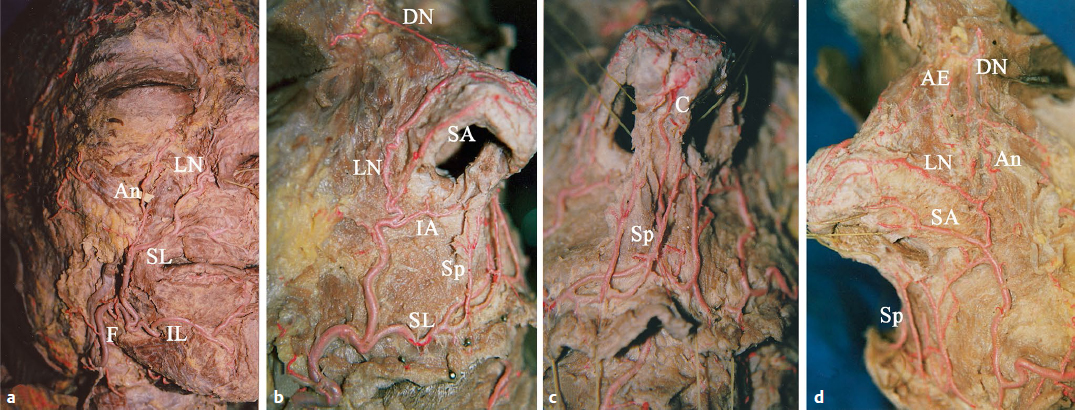

Fig. 6.8 Course of the facial artery and its branches. Red latex is injected into the common carotid arteries before dissection. (a) A doubled facial artery, (b) nasal-type facial artery. The anastomoses between alar branches and branches of the superior labial artery, and (c) septal branch are continued as the columellar artery. (d) Angular type facial artery. The anastomoses between the superficial ascending artery and inferior alar branch. AE, anterior ethmoidal artery; An, angular artery; C, columellar artery; DN, dorsal nasal artery; F, facial artery; IA, inferior alar artery; IL, inferior labial artery; LN, lateral nasal artery; SA, superior alar artery; SL, superior labial artery; Sp, septal artery.

Surgical Annotation

The origins of the inferior labial artery vary between the labial commissure and the lower margin of the mandible. The inferior labial artery can arise from the facial artery above the labial commissure (8%), below the labial commissure (22%), and at the labial commissure (60%).10,18,20 The inferior labial and labiomental arteries come off at the level of the inferior border of the buccinator muscle and run anteriorly, passing deep to the depressor anguli oris. Different arterial distributions exist in the lower lip such as end-to-end anastomosis between the bilateral inferior labial arteries and the inferior labial arteries anastomose with the submental artery. The vertical and horizontal labiomental arteries are situated between the lower lip and the submental region (transfacial anastomosis). The distances from the labial commissure are 29.1 ± 24.2 mm (7–71 mm) to the origin of the horizontal labiomental arteries and 28 ± 12.1 mm (10–52 mm) to the origin of the vertical labiomental arteries. The lengths of the horizontal labiomental arteries are 26.8 ± 10.7 mm (16–49 mm) and the vertical labiomental arteries are 13 ± 4 mm (1–17 mm).10,18,20,21 The labiomental arteries, which form anastomoses between the facial, inferior labial, and submental arteries, vary in their course in the labiomental region (Fig. 6.1).10,18,20,21 To elevate a labiomental arterial flap safely, routine use of a Doppler probe preoperatively and intraoperatively is recommended.7,10

Superior Labial Artery

The facial artery passes deep to the risorius and zygomaticus major muscles but superficial to the buccinator muscle. It gives off one of its major branches, the superior labial artery. Near the labial commissure, it gives off three to five branches to the anterior part of the buccinator and zygomaticus major muscles (Fig. 6.8).20

The arterial supply to the lips is based on the superior and inferior labial arteries at the level of the labial commissure, where it terminates in the form of a perilabial arterial network (Fig. 6.4b, transfacial anastomosis). The arterial supply to the upper lip arises mainly from the superior labial artery and from the subseptal and subalar arteries. The arterial supply to the lower lip arises from the inferior labial artery and the branches of the mental artery.11,18

Surgical Annotation

The superior labial artery is larger and more tortuous than the inferior labial artery. It originates as follows: at the level of the labial commissure in 5% of cases, superior to the commissure in 25%, and inferior to the commissure in 70%. It can be identified usually 8 ± 4.4 mm (1–18 mm) lateral to the medial labial commissure. Its length is 4.8 ± 12.2 mm (29–67 mm). In 84.8%, the artery travels exclusively between the orbicularis oris muscle and the oral mucosa; in 15.2%, it travels partially invested by the orbicularis oris. It supplies the upper lip and gives off two or three vessels that ascend to the nose: a septal branch ramifies on the nasal septum, and an alar branch supplies the ala of the nose (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.8).10,18,20,21 A relatively large branch that courses along the inferior margin of the nostril on its ascent toward the columellar base is called the inferior alar branch, and the artery running to the nasal tip over the ala nasi is called the superior alar branch. The inferior alar branch supplies the alar base, the nostril floor, and the upper lip; the superior alar branch participates in the vascular plexus of the nasal dorsum and the tip. The length of the superior alar branch is 14.6 ± 5.9 mm (7–26 mm), and that of the septal branch is 15.6 ± 6.2 mm (10–27 mm).10,18,20

The superior labial artery runs between the mucosa and orbicularis oris at approximately the border between the white and the red parts of the lips and anastomoses with the opposite artery in the middle of the lip.6,7 The distances from the superior labial artery at midlip are 6.9 ± 2.5 mm (0.7–11 mm) to the inferior border of the red upper lip, 5.4 ± 1.8 mm (3–9 mm) to its anterior border, and 3.2 ± 0.7 mm to its posterior border.10,18,20

These branches are named as two groups: those running between the skin and the muscle are called superficial ascending branches, and those running through the muscle or between the muscle and the mucosa are called deep ascending branches. At the columellar base, there are anastomoses among the superficial ascending and inferior alar arterial branches. Ramifications of the deep ascending and inferior alar branches pass to the nasal septum and ascend along the anterior margin of the septal cartilage. Columellar branches are the continuation of the superficial ascending branches and become part of the vascular plexus of the nasal tip (Fig. 6.8b–d). The columellar artery is observed as a single branch in 48.9% and a double pattern in 38.7%.20

Lateral Nasal Artery

The lateral nasal artery arises from the facial artery at the nasolabial sulcus level. It runs 2 to 3 mm superior to the alar groove, extends between the nose and the cheek, and gives off the superior and inferior alar arteries to supply the nose (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.8). The lateral nasal artery anastomoses with its fellow, with the septal and alar branches, with the dorsal nasal branch of the ophthalmic, and with the infraorbital branch of the maxillary arteries (Fig. 6.1). The facial artery continues as the angular artery and proceeds to the medial palpebral commissure.6,7

Surgical Annotation

Small distal branches of the lateral nasal artery form several anastomoses with contralateral have branches and with the columellar arteries.5,6,18 Some studies demonstrated the existence of an anastomotic system, situated in the superior musculoaponeurotic system plane, connecting the external and the internal carotid artery systems and the transfacial nasal vascular blood supply, which gives rise to the subdermal plexus. This network explains why many different pedicles can be safely used for local flaps in nasal reconstruction (Fig. 6.4c, polygonal system anastomosis). Furthermore, after skin tumor resections, the presence of these anastomotic vessels enables a large vessel ligation to be performed without skin necrosis; however, the presence of so many anastomotic vessels in the nasal area can be easily injured during injections, and creates a risk of embolism or microembolism, especially with rhinoplasties using fillers (Fig. 6.4a, intercarotid anastomosis).

Angular Artery

The angular artery is the terminal part of the facial artery; it ascends to the medial angle of the orbit and is accompanied by the angular vein. It is easily found on a vertical line about 6 to 8 mm medial to the medial canthus and 5 mm anterior to the lacrimal sac. In 60% of specimens, the terminal branch is formed by the lateral nasal artery, and in 22% it is formed by the angular artery. It anastomoses with the infraorbital artery on the cheek after supplying the lacrimal sac and the orbicularis oculi. The angular artery ends by anastomosing with the dorsal nasal branch of the ophthalmic artery (Fig. 6.1, Fig. 6.8c).11 Its branches are a communicating branch with the dorsal nasal artery (96%), a communicating branch with the supratrochlear artery (67%), the infratrochlear artery, and the paracentral artery. The paracentral artery originates from the angular artery as the main continuation into the forehead (71%) or from the communicating branch with the supratrochlear artery (30%).7,11,20,22

Surgical Annotation

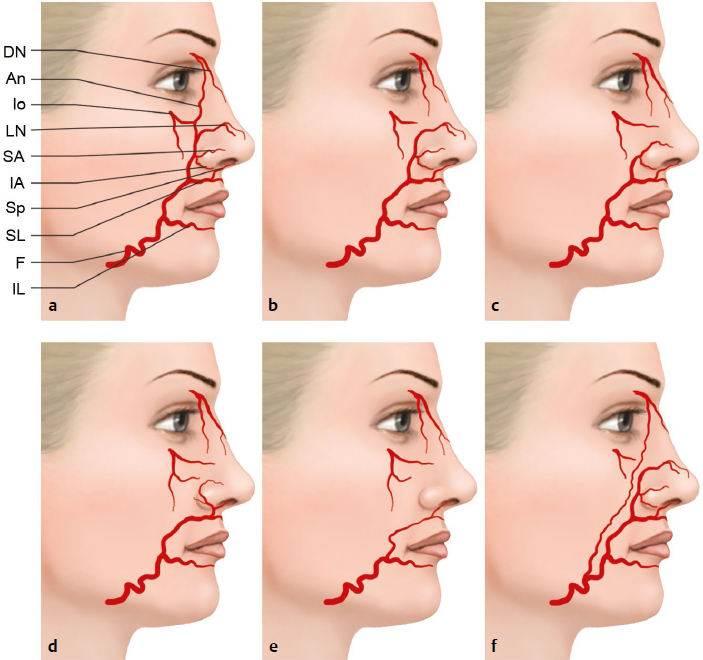

Difficult oronasal mucosal defects, including defects of the palate, alveolus, nasal septum, antrum, upper lip and lower lip, floor of the mouth, and soft palate, can be reconstructed using an axial musculomucosal flap based on the facial artery and its branches. Their diameters are suitable for microvascular anastomosis.6,7,11,20 Most of these flaps are based on local axial vascularization via the labial arteries, but anatomical variations can lead to problems; its branching pattern shows great variability (Fig. 6.8a, Fig. 6.9). The distribution patterns of the artery are categorized into six types, A–F (Fig. 6.9).6,7,11,20 In type A (47–78%) the artery bifurcates into the superior labial and lateral nasal arteries (the latter gives off the inferior and superior alar and ends as the angular artery). Type B (38–60%) is similar to type A except the lateral nasal terminates as the superior alar (the angular artery is absent). In type C (8–12%), the facial artery terminates as the superior labial artery. In type D (3.8%), the angular artery arises directly from the facial arterial trunk rather than as the termination of the lateral nasal, with the facial artery ending as the superior alar. In type E (1.4–3%), the facial artery terminates as a rudimentary twig without providing significant branches. Type F presents a doubled facial artery.23 On the basis of anatomical studies, the degree of vascular territory lost as a result of vessel damage during the myocutaneous flap procedure can be estimated. For example, ligation of the superior labial artery in a patient with type A, B, or C would not result in ischemic injury to the nose, as the blood supply is provided by a separate lateral nasal artery. In contrast, ligation of the superior labial artery in a patient with type D or E distribution is more likely to result in loss of the vascular supply to the lateral nose.7,10

The facial musculomucosal flap is an axial flap based on the superior labial artery in an anterograde fashion or the angular artery in a retrograde fashion.3,7,10 The nasolabial flap can be based on the angular artery either inferiorly or superiorly in an anterograde or retrograde fashion, respectively. Doppler ultrasound helps to locate the facial vessels and provides information about backflow and the potential for inverted flow in the facial artery.7,10

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree