Chapter 1 Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is the sixth most common procedure performed in orthopaedics, and it is estimated that between 75,000 and 100,000 ACL repair procedures are performed annually in the United States alone.1,2 The ACL has therefore been intensively studied, and outcomes of ACL surgery have received considerable attention. This has included research on surgical technique factors such as tunnel position, graft choices, and fixation methods, as well as postoperative rehabilitation protocols.

Traditional single-bundle ACL reconstruction has focused on reconstruction of one portion of the ACL, the anteromedial (AM) bundle, and although outcomes are generally good, with success rates between 69% and 95%, there remains room for improvement.3,4 A prospective study of a cohort of ACL reconstructed patients 7 years after surgery revealed degenerative radiographic changes in 95% of patients, and only 47% were able to return to their previous activity level following ACL reconstruction.5 However, it should be noted that some studies of long-term follow-up have more encouraging results. Jarvela et al demonstrated tibiofemoral degenerative changes in only 18% of patients at 7 years follow-up post ACL reconstruction with bone–patella–bone grafts.6 In addition, Roe et al reported on a cohort of patients reconstructed with bone–patellar tendon–bone grafts and found an incidence of 45% with degenerative radiographic changes at 7 years follow-up, as well as an incidence of 14% with degenerative changes in a group with hamstring grafts.7

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Anatomy

Historical Descriptions

Two bundles of the ACL were described for the first time in 1938 by Palmer et al, followed by Abbott et al in 1944 and Girgis et al in 1975.8–10 Each author described an AM bundle and a posterolateral (PL) bundle, named for the relative location of the tibial insertion sites of each bundle. More recently, in 1979 and again in 1991, Norwood et al and Amis et al, respectively, described a third bundle of the ACL anatomy, the intermediate (IM) bundle.11,12 Although it may be said that a two-bundle description of the ACL anatomy is an oversimplification of the complete anatomy, many studies have been based on this functional division, and it has been accepted as a reasonable way to understand the anatomy and biomechanics of the ligament. The IM bundle is most similar to the AM bundle in both anatomical and biomechanical considerations, and for the purposes of this chapter it is therefore considered as part of the AM bundle.

Anatomy of the Anteromedial and Posterolateral Bundles

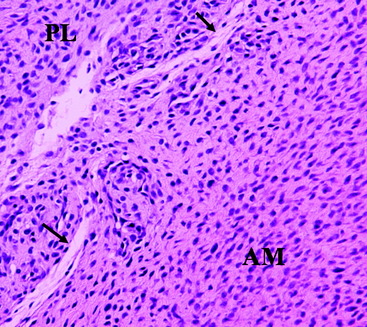

The ACL is a structure composed of numerous fascicles of dense connective tissue that connect the distal femur and the proximal tibia. Histological studies have demonstrated that a septum of vascularized connective tissue is present that separates the AM and PL bundles (Fig. 1-1). In addition, it has been shown that the histological properties of the ligament are variable at different stages in ACL development. At the time of fetal ACL development, the ACL is observed to be hypercellular with circular, oval, and fusiform-shaped cells. Later, in the adult ACL, the histology reveals a relatively hypocellular pattern with predominantly fibroblast cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.13,14

The ligament finds its origin on the medial surface of the lateral femoral condyle (LFC), runs an oblique course within the knee joint from lateral and posterior to medial and anterior, and inserts into a broad area of the central tibial plateau. The cross-sectional area of the ligament varies significantly throughout its course from approximately 44 mm2 at the midsubstance to more than three times as much at both its origin and insertion.10,15,16 The total length of the ligament is approximately 31 to 38 mm and varies by as much as 10% throughout a normal range of motion.17

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Development

ACL formation has been observed in fetal development as early as 8 weeks, corresponding to O’Rahilly stages 20 and 21.18,19 A leading hypothesis holds that the ACL originates as a ventral condensation of the fetal blastoma and gradually migrates posteriorly with the formation of the intercondylar space.20 The menisci are derived from the same blastoma condensation as the ACL, a finding that is consistent with the hypothesis that these structures function in concert.21 Another proposed mechanism of fetal ACL formation is from a confluence between ligamentous collagen fibers and fibers of the periosteum.22 Following the initial formation of the ligament, no major organizational or compositional changes are observed throughout the remainder of fetal development.19

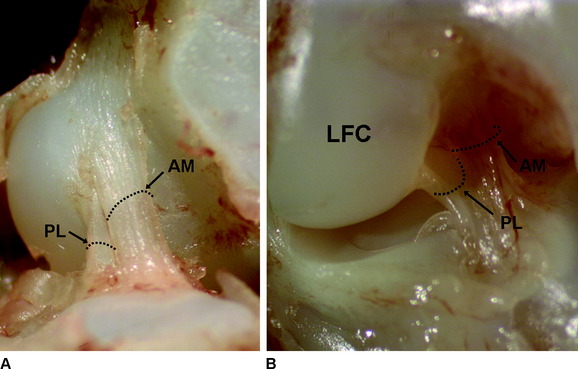

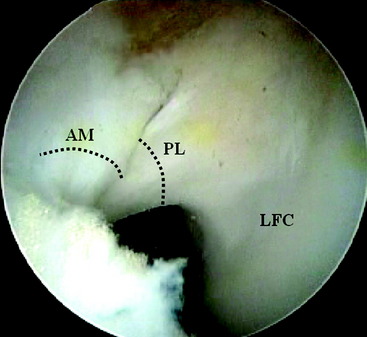

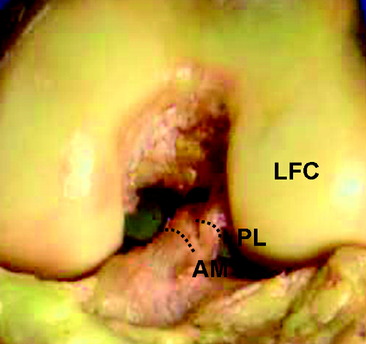

Two distinct bundles of the ACL are present at 16 weeks of gestation (Fig. 1-2). In arthroscopy, the AM and PL bundles can also be appreciated, particularly with the knee held in 90 to 120 degrees of flexion (Fig. 1-3). Finally, cadaveric dissection also reveals two anatomical bundles of the ACL (Fig. 1-4). In summary, there is a considerable amount of interindividual variability with respect to the relative sizes of the AM and PL bundles, as seen in fetal, arthroscopic, and cadaveric studies; however, all individuals with an intact ACL have both bundles of ligament.

Insertion Site Anatomy

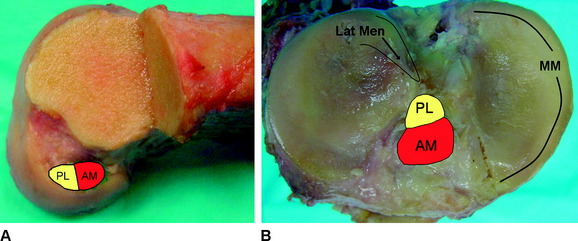

Anatomical studies have characterized the individual contributions of both the AM and PL bundles to the overall ACL architecture. Odensten and Gillquist described the femoral origin of the ACL as an ovoid area measuring 18 mm in length and 11 mm in width.23 Within this area, the AM bundle occupies a position located on the proximal portion of the medial wall of the LFC, and the PL bundle occupies a more distal position near the anterior articular cartilage surface of the LFC (Fig. 1-5, A). Harner et al studied the digitized origin and insertion of the AM and PL bundles in five cadavers and concluded that each bundle occupies approximately 50% of the total femoral origin, with cross-sectional areas of 47 ± 13 mm2 and 49 ± 13 mm2 for AM and PL, respectively. 16

On the tibia, the insertions of the AM and PL bundles are located between the medial and lateral tibial spine over a broad area stretching as far posterior as the posterior root of the lateral meniscus. The full ACL insertion has been described as an oval area measuring 11 mm in diameter in the coronal plane and 17 mm in the sagittal plane.10,15,24 Within this area the AM bundle insertion can be found in an anterior and medial position, whereas the PL bundle insertion is located more posteriorly and laterally (Fig. 1-5, B

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree