Amyloidosis of the Skin: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Amyloidosis is a rare condition and the exact incidence remains unclear. The overall sex and age adjusted rate per million person years was reported as 6.1 from 1950 to 1969 and 10.5 from 1970 to 1989 in the United States of America, and localized amyloidosis accounts for less than 10% of all diagnoses. Both localized and systemic forms of the disease become more frequent with age, and presentation before the age of 30 years is extremely unusual. No known racial, occupational, geographic, or other environmental factors have been implicated in the genesis of systemic amyloidosis, although there is evidence for a slight male preponderance.

Amyloidosis is caused by extracellular deposition of insoluble abnormal fibrils, derived from the aggregation of misfolded protein.1,2 At least 26 unrelated proteins are known to form human amyloid fibrilsin vivo.3 The ultrastructural morphology and histochemical properties of all amyloid fibrils, regardless of the precursor protein type, are remarkably similar and fibril diffraction studies have confirmed that they all share a common core structure consisting of a cross β core and polypeptide chains lying perpendicular to the long axis of the fibril. This extremely abnormal, highly ordered conformation underlies the distinctive physicochemical properties of amyloid fibrils, including their relative stability and resistance to proteolysis. Amyloid deposits universally contain the normal plasma glycoprotein, serum amyloid P component (SAP), and heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycan chains as nonfibrillar constituents Other plasma proteins, such as apolipoprotein E, are sometimes detectable in amyloid deposits, but without the universality and abundance of SAP.

Amyloid formation in vivo occurs with both normal wild-type proteins and with genetically variant proteins. The fibrils may contain the intact amyloidogenic protein or proteolytic cleavage fragments. There is always a lag period, often of many years, between first appearance of the potentially amyloidogenic protein and the deposition of clinically significant amyloid. There are many ways of classifying amyloidosis of which the most useful is according to the deposited protein (Table 133-1). In addition, it is vital to determine whether the amyloid deposits are localized, distributed in only one tissue or organ, or deposited more widely.

Type | Fibril Protein Precursor | Clinical Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

AA | Serum amyloid A protein | Reactive systemic amyloidosis associated with chronic inflammatory diseases |

AL | Monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains | Systemic amyloidosis associated with monoclonal plasma cell dyscrasias |

Aβ2M | β2-microglobulin | Periarticular and, occasionally, systemic amyloidosis associated with long-term dialysis |

ATTR | Normal plasma transthyretin | Senile systemic amyloidosis with prominent cardiac involvement |

ATTR | Genetically variant transthyretin | Autosomal dominant systemic amyloidosis Familial amyloid polyneuropathy |

ACys | Genetically variant cystatin C | Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with cerebral and systemic amyloidosis |

AGel | Genetically variant gelsolin | Autosomal dominant systemic amyloidosis Predominant cranial nerve involvement with lattice corneal dystrophy |

ALECT2 | Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin-2 (LECT2) | Systemic amyloidosis with predominant renal involvement |

ALys | Genetically variant lysozyme | Autosomal dominant systemic amyloidosis Non-neuropathic with prominent liver and renal involvement |

AApoAI | Genetically variant apolipoprotein AI | Autosomal dominant systemic amyloidosis May be neuropathic, prominent liver and renal involvement |

AApoAII | Genetically variant apolipoprotein AII | Autosomal dominant systemic amyloidosis Non-neuropathic with prominent renal involvement |

AFib | Genetically variant fibrinogen A α chain | Autosomal dominant systemic amyloidosis Non-neuropathic with prominent renal involvement |

This is the commonest type of systemic amyloidosis, accounting for more than 60% of cases. AL amyloidosis may occur in association with any monoclonal B cell dyscrasia.4 AL fibrils are derived from monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains and consist of the whole or part of the variable (VL) domain.5 A degree of amyloid deposition is seen in up to 15% of patients with myeloma, but the vast majority, more than 80%, of patients who present with clinically significant AL amyloidosis have very low grade and otherwise “benign” monoclonal gammopathies.

Reactive systemic, AA, amyloidosis is a potential complication of any disorder associated with a sustained acute phase response and the list of chronic inflammatory, infective, or neoplastic disorders that can underlie it is almost without limit.6 Although 60% of patients have inflammatory arthritis, some of the underlying diseases have cutaneous features that may facilitate diagnosis. These include: psoriatic arthritis, epidermolysis bullosa, basal cell carcinoma, chronic cutaneous ulcers, and hereditary periodic fever syndromes, particularly cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS) and TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS).7 Biopsy and postmortem series suggest that the prevalence of AA amyloid deposition in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases is between 3.6% and 5.8%, though a smaller proportion of patients have clinically significant amyloidosis. The amyloid fibrils are derived from the circulating acute phase reactant, serum amyloid A protein (SAA). SAA is an apolipoprotein of high-density lipoprotein (HDL)8 which, like C-reactive protein (CRP), is synthesized by hepatocytes under the transcriptional regulation of cytokines. A sustained high plasma level of SAA is a prerequisite for the development of AA amyloidosis, but why amyloidosis develops in only a small proportion of cases remains unclear.

These are very rare autosomal dominantly inherited conditions. The most common cause of hereditary amyloidosis is mutations in the gene for transthyretin (TTR), which affects around 10,000 individuals worldwide, and causes familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP). The other hereditary systemic amyloidoses are derived from apolipoproteins AI and AII, fibrinogen A α chain, gelsolin, and lysozyme.9

Localized amyloid deposition is not uncommon, although often undiagnosed, and reportedly accounts for 9.3% of all amyloidosis.10 It results either from local production of fibril precursors or from properties inherent to the particular microenvironment, which favor fibril formation of a widely distributed precursor protein. The vast majority of deposits are AL in type, and symptomatic deposits occur most frequently in the eye, skin, gastrointestinal, respiratory, or urogenital tracts.8 They are often associated with extremely subtle focal monoclonal B cell proliferation confined to the affected site and surgical resection of these localized “amyloidomas” can sometimes be curative. Symptomatic apparently localized amyloid deposits can rarely be manifestations of systemic disease and patients should always be fully investigated to exclude more generalized amyloid deposition.11 Progression from localized to systemic amyloidosis is very rare. In lichen and macular amyloidosis, the fibrils are derived from proteins released from apoptotic keratinocytes. The etiology is not entirely clear but the association with other pruritic conditions suggests that mechanical factors associated with chronic scratching and skin friction are probably crucial.12

Clinical Findings

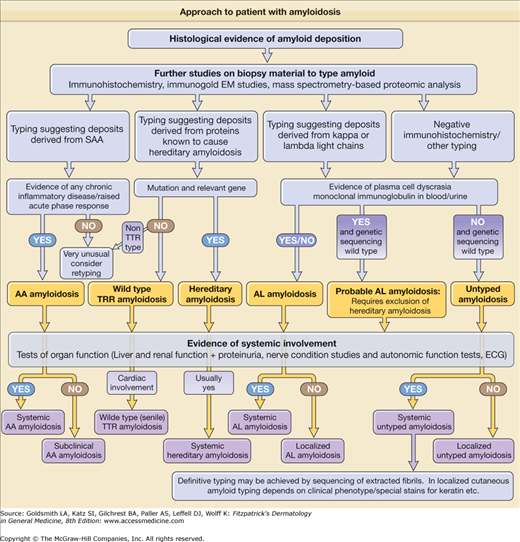

(See Fig. 133-1)

In the majority of patients with systemic amyloidosis the presentation is nonspecific, and as a result amyloid is often an unexpected finding on biopsy of an affected organ.

AL amyloid usually presents in patients over the age of 50 years, although it can present in very young adults.4 In the majority of cases, the underlying plasma call clone is not detected prior to presentation with amyloid-related organ dysfunction. Clinical manifestations are extremely variable since almost any organ other than the brain can be directly involved.13 Although certain clinical features such as macroglossia and periorbital ecchymoses are very strongly suggestive of AL amyloidosis (Table 133-2), and multiple vital organ dysfunction is common, many patients present with nonspecific symptoms such as malaise and weight loss.

Visible tissue infiltration | Bruising (particularly periorbital) Macroglossia Muscle or joint pseudohypertrophy |

Renal | Proteinuria Hypertension Chronic renal failure |

Cardiac | Restrictive cardiomyopathy Arrhythmias Congestive cardiac failure |

Hepatic | Hepatomegaly Liver failure (very rare) |

Peripheral nervous system | Carpal tunnel syndrome Symmetrical sensorimotor neuropathy |

Autonomic nervous system | Orthostatic hypotension Impotence Disturbed bowel motility Impaired bladder emptying |

Gastrointestinal | Weight loss GI blood loss Disturbed bowel motility |

Lymphoretiicular | Splenomegaly Lymphadenopathy |

Adrenal axis | Hypoadrenalism |

AA amyloidosis can present anytime between childhood and old age with a median age at presentation of 48 years in the United Kingdom. Almost 95% of patients have a clinically overt previously diagnosed chronic inflammatory disease such as rheumatoid or one of the other inflammatory arthritides, chronic sepsis usually bronchiectasis, complications of paraplegic conditions, or drug abuse. It is slightly more common in men. Although the disease can develop very rapidly, the median latency between presentation with a chronic inflammatory disorder and clinically significant amyloidosis is almost two decades. It usually presents with proteinuria and subsequently progressive renal dysfunction, often accompanied by nephrotic syndrome.6

The presentation of hereditary amyloidosis varies depending on the variant protein, mutation, and even within kindreds.14,15 Severe progressive peripheral and/or autonomic neuropathy is the major feature of hereditary TTR amyloidosis (FAP), but cardiac involvement is also common. ApoAI amyloidosis sometimes causes neuropathy, but this is not a feature of the other hereditary types, which typically involve the viscera. All the amyloidogenic mutations are dominant, but they are variably penetrant and therefore a family history may be absent.

Cutaneous manifestations are common in systemic amyloidosis, particularly the AL type, and are reported in up to 40% of patients.4 The lesions usually reflect capillary infiltration and fragility with petechiae and purpura, particularly affecting the eyelids, beard area, and upper chest (Fig. 133-2A).16 Xanthomatous papules or plaques are also frequently observed and amyloidotic hyperpigmented keratotic lesions have been reported occasionally. Other rare cutaneous lesions include scleroderma-like changes (Fig. 133-2B), alopecia, and nail dystrophy (Fig. 133-2C). Bullous amyloidosis affecting the skin and mucosa has been described.17 The bullae can be intradermal or subepidermal and present as tense, often hemorrhagic blisters. Generalized infiltration of cutaneous tissues can frequently cause the appearance of skin thickening with loss of facial wrinkles and can limit mouth opening.

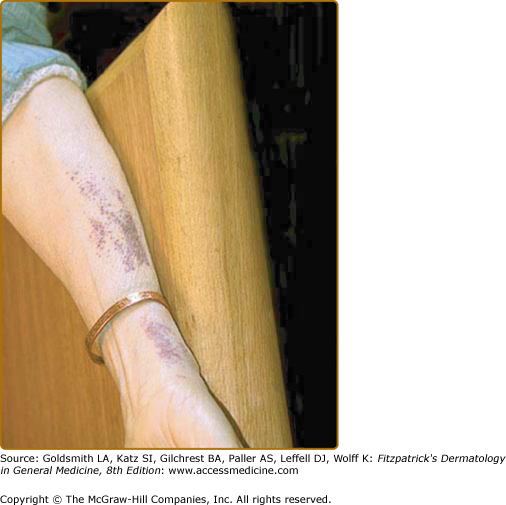

Lysozyme amyloidosis frequently causes petechial eruptions (Fig. 133-3) and apolipoprotein AI amyloidosis can also manifest as yellowish infiltrated plaques and acanthosis nigricans-type lesions.15,18 Cutaneous lesions in FAP seem to be largely due to the peripheral neuropathy. They manifest as xerosis in 82%, seborrheic dermatitis in 22%, trauma or burn lesions in 20%, neuropathic ulcers in 14%, and onychomycosis in 10.5% of patients.19

As in systemic AL amyloidosis, the fibrils are derived from N-terminal cleavage fragments of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains. The lesions are those seen in systemic AL amyloidosis and present as single or more frequently multiple lesions anywhere on the skin.20 In our series of 20 patients; 35% had indolent papular, nodular, or xanthomatous lesions (Fig. 133-4), 20% purpuric rash, 20% pruritus, 15% local bleeding, and 10% localized swelling. In only 15% of cases were the lesions painful.21

Macular and lichen amyloidosis are variants of a single pathology in which the amyloid fibrils are derived from galectin-7 following epidermal damage and keratinocyte apoptosis.22 They are usually idiopathic or friction related, but have been reported in association with connective tissue diseases (primary biliary cirrhosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome)23 and in a few kindreds with pachyonychia congenita24 or multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2a.25

Macular amyloidosis usually affects the upper back and limbs and can persist for many years. The rash is pruritic in the great majority of cases and consists of small brownish macules distributed in a rippled pattern. There may be a female preponderance,26 and it is more common among Central and South Americans, Middle Easterners, and non-Chinese Asians. Amyloid deposits usually are confined to the papillary dermis and do not involve blood vessels or adnexal structures. Early lesions contain small, multifaceted, amorphous globules within the papillae, and these are missed easily without the use of special stains. Later lesions show globules that coalesce, expand the papillae, and displace the rete ridges laterally. Lichen amyloidosis is the commonest type of cutaneous amyloidosis in Chinese individuals and usually affects adults.12,27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree