19 Alternative flaps for breast reconstruction

Synopsis

Many women today have undergone procedures on their abdomen, such as liposuction and abdominoplasty, that preclude the TRAM/DIEP breast reconstructive option.

Many women today have undergone procedures on their abdomen, such as liposuction and abdominoplasty, that preclude the TRAM/DIEP breast reconstructive option.

The skilled microsurgeon needs to be able to utilize other flaps for women in this category.

The skilled microsurgeon needs to be able to utilize other flaps for women in this category.

Alternative flaps may include transverse upper gracilis free flap (TUG); superior gluteal artery free flap (SGAP); inferior gluteal myocutaneous flap (IGAP); deep femoral artery perforator (DFAP), and lumbar artery perforator flap (LAP).

Alternative flaps may include transverse upper gracilis free flap (TUG); superior gluteal artery free flap (SGAP); inferior gluteal myocutaneous flap (IGAP); deep femoral artery perforator (DFAP), and lumbar artery perforator flap (LAP).

Introduction

The modern era of autogenous breast reconstruction began with the TRAM flap, popularized by Dr Carl Hartrampf in the early 1980s. This was the procedure of choice until the 1990s, when the goal of muscle preservation became more apparent. Perforator flap breast reconstruction in the early 1990s by the authors’ group at Louisiana State University Medical Center was the next significant advance in breast reconstruction. By injecting fresh abdominoplasty specimens, it was determined that the skin and fat could be transferred without sacrifice of the rectus abdominus muscle. This led to the first DIEP flap for breast reconstruction by Allen in 1992.1 The inception of free tissue transfer allowed an infinite range of possibilities to appropriately match donor and recipient sites.2

History

Transverse upper gracilis free flap (TUG)

Orticochea in 1972 was the first to describe immediate transfer of a large amount of skin without using the ever popular delay maneuvre.3 The premise of the skin survival was thought to be through the vasculature supplying the underlying muscle. This was the concept for the TUG flap. McGraw et al. improved upon this theory by conceptualizing the idea of a perforator vessel otherwise known as musculocutaneous perforators.4 The gracilis free flap became widely accepted and used, however the skin paddle overlying the muscle, when included, became precarious for survival. Yousif et al. in 1992 mapped out the gracilis muscle perforators and devised a transverse skin orientation using the upper third of the muscle with predictable reliability of the skin paddle.5,6

Hallock in 2003, reported modifications of the TUG flap by identifying the perforator off of the medial circumflex femoral artery. He used this flap predominantly for lower leg reconstruction for trauma patients.7 Also in the same year, the TUG flap based on the medial circumflex femoral artery was first described for breast reconstruction. Arnez et al. performed the free TUG flap on seven patients for breast reconstruction, five flaps were successful and two flaps were lost.8 Schoeller and Wechselberger in 2004 described 12 TUG flaps for breast reconstruction and all were successful.9 This paper has led to the current popularity of the TUG flap for breast reconstruction.

Peek et al. in 2005 further delineated the anatomy of the blood supply to the gracilis muscle and surrounding skin. His group described the variations of the TUG perforator flap for breast reconstruction. In 2009, he dissected 24 fresh cadavers defining the perforators into either a musculocutaneous or septocutaneous course.10 Finally, the superficial femoral artery perforator was first described by Beak in 1983 and Song et al. in 1984.11,12 This flap was first used by our group for breast reconstruction in 2008, where three flaps were performed for breast reconstruction.

Superior/inferior gluteal artery perforator free flap (SGAP/IGAP)

The superior gluteal myocutaneous free flap by Fujino was first described in 1975 for breast reconstruction. The myocutaneous superior gluteal artery free flap for breast reconstruction was popularized by Dr Bill Shaw.14–18 However, a short vascular pedicle frequently required vein grafting, increasing the difficulty and complications of this technique. The first breast reconstruction with an inferior gluteal myocutaneous flap was performed in 1978 by LeQuang.19

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Transverse upper gracilis free flap (TUG)

Anatomy

The gracilis muscle is a narrow muscle extending from the pubic tubercle to the medial upper surface of the tibia. Its actions include thigh adduction and flexion, as well as leg flexion and medial rotation. It is categorized as a type II muscle by Mathes and Nahai with one dominant and one minor pedicle.13 The motor innervation is by the obturator nerve arising from the lumbar plexus L3–L4 with its anterior branch supplying the gracilis muscle. The blood supply is from the medial circumflex femoral artery from the profunda femoris artery in which the dominant pedicle enters the medial aspect of the gracilis 6–10 cm inferior to the pubic tubercle. This vasculature then divides into a musculocutaneous and sometimes a septocutaneous branch. This division usually takes place in the upper third of the muscle. The venae comitantes follow the perforators and enter into the femoral vein. The saphenous vein also augments drainage to this area.

Treatment/surgical technique

Hints and tips

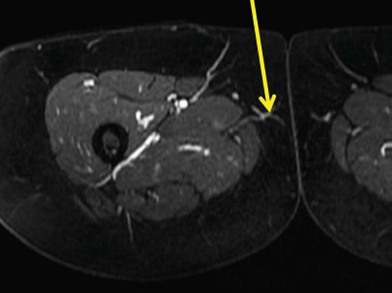

• Preoperative imaging will shorten your operative time by one-third.

• Always locate the adductor when the patient comes in for preoperative markings. It will make the dissection faster in the operating room due to the consistency of the anatomy in this flap.

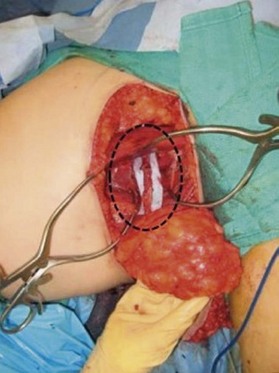

• Once the vessels are identified, dissect under the adductor from its posterior border, then switch to the anterior border to finish the dissection to the superficial femoral artery/vein.

• Keep the saphenous vein intact to keep the percentage of lymphedema minimal.

• Use a knife when dissecting the superior portion of the flap so as not to stun the lymph nodes and again to minimize lymphedema.

Complications

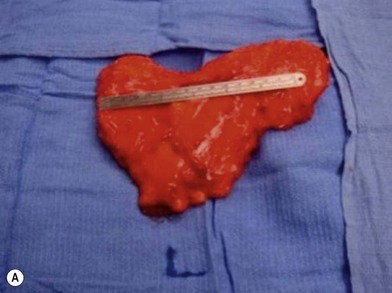

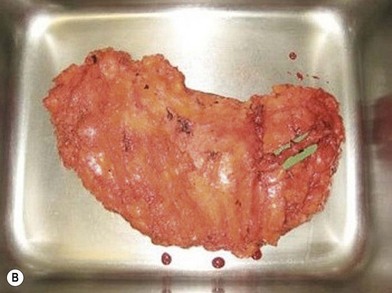

Distortion of the external genitalia or inferior migration of the scar has not occurred in our 71 cases. Preoperative placement of the upper incision near the inguinal crease helps hide the scar. Aesthetically, the upper thigh can be scooped out compared with the lower part. There is a natural narrowing of the thigh superiorly, so this is usually not an issue. If this becomes an issue, liposuction at a second stage can improve contour (Figs 19.1–19.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree