Adult Kidney Transplantation

Marc L. Melcher

Elyssa J. Feinberg

DEFINITION

Kidney transplant is the optimal treatment for end-stage kidney disease. The artery and vein from either a live or a deceased donor are anastomosed to a patient’s blood vessels. The ureter is anastomosed either directly to the bladder or to the native ureter.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A nephrologist, transplant surgeon, and transplant social worker should evaluate potential kidney transplant recipients. A history and physical examination is completed.

Laboratory tests include complete blood count (CBC); basic metabolic panel; liver function tests; coagulation panel; and screening for hepatitis B and C, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Absolute and relative contraindications for transplant are detailed in Table 1.

All recipients must be approved for transplantation by a multidisciplinary evaluation committee. This committee includes transplant surgeons, nephrologists, nurse coordinators, social workers, nutritionists, and financial coordinators.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Age- and gender-appropriate health screening procedures such as colonoscopy, mammogram, and prostate exams are completed.

Routine chest x-ray and electrocardiogram (EKG).

Cardiac evaluation is based on individual patient risk stratification.1 Many candidates have significant cardiovascular risk factors and merit close review.

Table 1: Contraindications to Renal Transplant

Active malignancy

Malignancy within 12-60 mo (depending on diagnosis)

Active infection

Profoundly debilitating brain injury

Active substance abuse

Severe multisystem failure

Long-standing medical noncompliance

Psychiatric illness

Inadequate social support

Active autoimmune diseases

ABO incompatibility with the donora

Positive T- and/or B-cell crossmatcha

HIV infectiona

a Kidney transplant is appropriate under specialized protocol.

If femoral pulses cannot be palpated or the patient has a history of vascular disease, obtain a duplex ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, or angiogram of the aortoiliac vessels. The noncontrast phase of the CT scan demonstrates vascular calcification and identifies a suitable location for vascular clamping.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

The immunosuppression regimen should be part of a protocol and established prior to the operating room (OR). Induction protocols vary by institution and are based on risk of rejection. Risk of rejection is related to the degree of sensitization, previous transplant, race, and age. Common induction regimens include methylprednisolone combined with either antithymocyte globulin or basiliximab.

The donor must be ABO-identical or compatible with the recipient, unless in an ABO-incompatible protocol. Tissue human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-typing and crossmatching should be performed. If the preliminary crossmatch is positive with a living donor, kidney exchange programs and desensitization protocols are an option.

Positioning

The patient is placed supine on the OR table. After general anesthesia is induced, invasive monitoring devices such as central venous catheter and arterial line are placed as deemed necessary by the anesthesia and surgical teams, although they are rarely needed.

A large-bore three-way Foley catheter is inserted to allow for bladder irrigation. Bladder irrigation distends the bladder facilitating the ureteroneocystostomy.

Extremity padding is placed to avoid pressure points and protect hemodialysis access.

Sequential compression devices are placed on the lower extremities.

Careful communication with anesthesia colleagues is critical. Generally, kidney transplant patients receive aggressive fluid resuscitation; adult patients receive 3 to 5 L of crystalloid solutions from the time of induction of anesthesia to the time of reperfusion of the kidney. This time can range from as short as 40 minutes to as long as several hours depending on case complexity and surgeon speed.

It is necessary that all members of the operative team are attentive for the surgical “time-out.” At this time, donor and recipient blood types as well as any additional administrative transplant-specific issues are reviewed. Although it seems intuitive, it is absolutely critical that the surgeon confirms that the appropriate organ is being transplanted into the appropriate recipient.

TECHNIQUES

SKIN INCISION

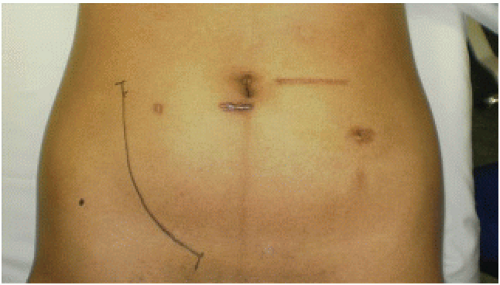

Palpate the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine for landmarks. Make a hockey stick-shaped incision from superior to the pubic tubercle upward along the lateral border of the rectus sheath, two to three fingerbreadths away from the anterior superior iliac spine (FIG 1).

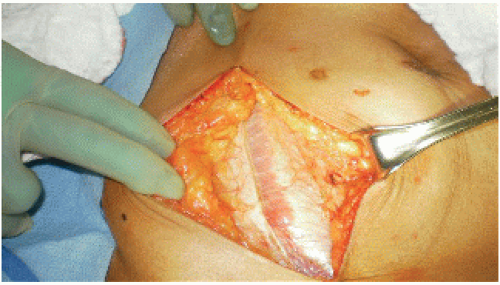

ENTERING THE RETROPERITONEUM

Divide the subcutaneous tissue until the fascia is reached. Incise the anterior sheath of the rectus abdominis. Continue superiorly along the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis to expose the retroperitoneum (FIG 2).

The inferior epigastric artery and vein are visualized in the lower one-third of the incision once the fascia has been opened. These vessels can be divided between ties as needed.

The spermatic cord in males and the round ligament in females are deep to the epigastric vessels. Isolate the spermatic cord and preserve it. Divide the round ligament.

The peritoneum is then swept medially with a combination of gentle blunt dissection and electrocautery. This opens the retroperitoneal space.

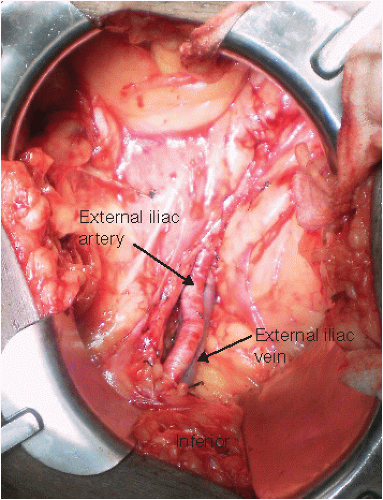

A retractor is assembled to facilitate exposure of the common, internal, and external artery and vein. Lay the blades so that two deep blades retract medially and one small blade retracts inferiorly along the vector of the artery. A lateral retractor is not usually needed.

VESSEL EXPOSURE

Ligate and divide the lymphatics overlying the external iliac artery and vein. Leakage of lymphatic fluid from this area can lead to a postoperative lymphocele.

The external iliac vessels are mobilized (FIG 3). If necessary, deep branches of the external iliac vein are ligated. This brings the vein to a more superficial position. This will facilitate the anastomosis when the donor vein is short and the recipient vessels are deep.

VENOUS ANASTOMOSIS

Place a Satinsky clamp on the external iliac vein to establish proximal and distal control. Ensure that the clamp does not include extra tissue that may compromise hemostasis. Plan the location of the arterial clamps; assessing the extent and location of iliac arterial calcification. Do not clamp the artery yet.

Prior to making a venotomy, bring the kidney onto the field and identify the location of the anastomoses on the recipient vessels using the donor vein and artery.

Wrap the kidney in icy 4 × 4 sponges to maintain orientation of the kidney during anastomosis (FIG 4).

Make a venotomy in the external iliac vein with a no. 11 blade. The lumen of the vessel is irrigated with heparinized saline and fine-pointed angled scissors are used to extend the venotomy (FIG 5). Make the iliac venotomy 10% larger that the renal vein. This will keep the renal vein on some tension during the anastomosis, lining up the walls of the vessels and facilitating the anastomosis. Appropriate sizing of the venotomy is the most important step in facilitating an easy venous anastomosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree