25 Abdominoplasty procedures

Synopsis

The abdominal area is the one of the most common areas treated in plastic surgery procedures. Mostly after pregnancies or weight changes, patients desire improvement of the abdominal wall, including the repair of additional ventral hernias.

The abdominal area is the one of the most common areas treated in plastic surgery procedures. Mostly after pregnancies or weight changes, patients desire improvement of the abdominal wall, including the repair of additional ventral hernias.

Assessment of the abdominal region includes a detailed medical and physical history, including pregnancies, prior surgeries especially in the lower truncal area, and weight changes. Preoperative identification of any existing ventral hernia including diastasis recti is imperative.

Assessment of the abdominal region includes a detailed medical and physical history, including pregnancies, prior surgeries especially in the lower truncal area, and weight changes. Preoperative identification of any existing ventral hernia including diastasis recti is imperative.

Essential issues of abdominal findings are the existence and localization of vertical and horizontal tissue excess, the relation of fatty and skin excess, the examination of the umbilical stalk with exclusion of umbilical hernia. Further perioperative issues are preoperative bowel evacuation for reduction of intraabdominal pressure, careful intraoperative handling, maintenance of an adequate body temperature, sufficient medical thromboembolism prophylaxis, precise intraoperative preparation with respect to anatomical key points, postoperative compression treatment and early management of postoperative complications such as seromas.

Essential issues of abdominal findings are the existence and localization of vertical and horizontal tissue excess, the relation of fatty and skin excess, the examination of the umbilical stalk with exclusion of umbilical hernia. Further perioperative issues are preoperative bowel evacuation for reduction of intraabdominal pressure, careful intraoperative handling, maintenance of an adequate body temperature, sufficient medical thromboembolism prophylaxis, precise intraoperative preparation with respect to anatomical key points, postoperative compression treatment and early management of postoperative complications such as seromas.

The “fleur-de-lis” abdominoplasty allows an improvement of the entire abdominal area with simultaneous tightening of the waist circumference. It is essential to initially assess and temporarily close the vertical line prior to resection of the lower abdominal redundant tissue. Care should be taken to avoid extending the vertical incision line cranially between the breasts.

The “fleur-de-lis” abdominoplasty allows an improvement of the entire abdominal area with simultaneous tightening of the waist circumference. It is essential to initially assess and temporarily close the vertical line prior to resection of the lower abdominal redundant tissue. Care should be taken to avoid extending the vertical incision line cranially between the breasts.

In patients with massive weight loss (MWL), aesthetic outcome will improve by high-lateral-tension and fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty, and in most cases, circumferential truncal procedures are necessary for superior results.

In patients with massive weight loss (MWL), aesthetic outcome will improve by high-lateral-tension and fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty, and in most cases, circumferential truncal procedures are necessary for superior results.

The preparation epifascial to the Scarpa fascia allows a preservation of subfascial lymphatic vessels for prevention of seroma formation and enables an additional tightening of Scarpa fascia for improvement of the inner thigh region.

The preparation epifascial to the Scarpa fascia allows a preservation of subfascial lymphatic vessels for prevention of seroma formation and enables an additional tightening of Scarpa fascia for improvement of the inner thigh region.

It is mandatory to analyze any suspected skin tumor in the area of excised tissue.

It is mandatory to analyze any suspected skin tumor in the area of excised tissue.

Introduction

Due to the number of variations and modifications of abdominoplasties, it is key to select the appropriate technique in every individual case, determining the best procedure by minimizing morbidity and postoperative disability for desirable and predictable results.1

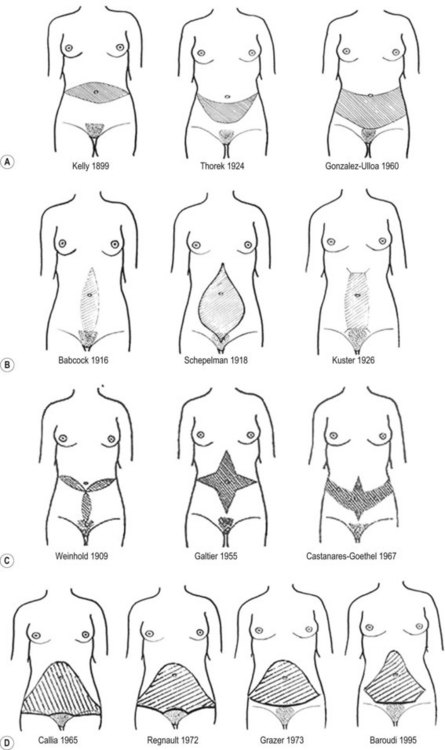

History

One of the first publications in abdominal wall surgery dates back to 1899. Kelly attempted to correct excess abdominal skin and fat using a large horizontal midabdominal incision,2,3 resecting a panniculus weighing over 7000 g. In 1916, Babcock presented a vertical midline incision.4 Since that time, numerous variations have been suggested. Thorek (1924) was the first to devise an abdominal procedure including the nowadays preferred lower transverse incision that preserved the umbilicus.5,6

In 1957, Vernon published a modern version of abdominoplasty, including an umbilical transposition and plication of the musculoaponeurotic layer.7 Pitanguy reported in 1967 of 300 abdominal lipectomies,8 Regnault published the W-technique for abdominoplasty in 1972.9 In 1973, Grazer described the so-called bikini line incision.10 The St Tropez bikini, fashioned in the 1960s with a very low waistline, favored the abdominoplasty with a nearly horizontal incision. In the mid-1980s, the French-line bikini (cut high at the lateral aspect and low centrally) became popular, favoring the abdominoplasty incision to be converted from a nearly horizontal line to an incision line that accompanied the inguinal fold.9,10 Nowadays, bikinis with very low waistlines have gained higher popularity again. Therefore, proper adjustments in every single technique, is necessary to achieve a tailor-made abdominoplasty.

In 1977, Grazer and Goldwyn reported the first complications using new abdominoplasty techniques.11 They had noted the ability to reduce the anterior projection of the abdominal wall by aponeurotic suturing without decreasing the diameter of the waist. Psillakis published, in 1978, the external belt for extensive waist diameter reduction by suture plication of the external oblique muscle after raising it in a beltlike fashion.12

The addition of liposuction to body contouring surgery in the 1980s allowed a further evolution of abdominoplasty procedures. In 1985, Dellon published the new approach to a combined vertical and transverse resection of the abdominal wall resulting in a fleur-de-lis pattern.13 Matarasso expanded, in 1988, the use of abdominal contour surgery to a classification based on variations in patients’ anatomy, from liposuction alone to limited and full abdominoplastic surgery.14

Ted Lockwood described the high lateral tension abdominoplasty in 1997, differing from conventional abdominoplasty by limited direct undermining, increased lateral skin resection with high tension wound closure along the lateral flanks with reconstruction of the superficial fascial system (SFS).15

In 2001, Saldanha published a new technique combining lipoplasty with traditional abdominoplasty without undermining of the abdominal flap, followed by modifications of this technique by extended undermining (Fig. 25.1).16

According to the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAP)’s 2008 Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank, the number of abdominoplasty procedures performed has increased approximately 333% since 1997.17

Anatomy

Abdominal skin and fat tend to be distributed in the lower abdomen with aging and pregnancy. Especially as a result of multiple pregnancies, striae become common, resulting in a rupture and separation of dermal collagen with consequent skin thinning.18 At this time, the therapy of striae is exclusively by surgical excision (Fig. 25.2).

Skin, muscle, and fascia

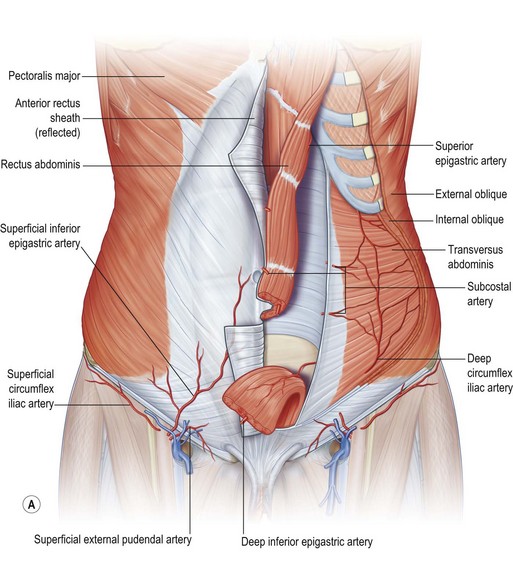

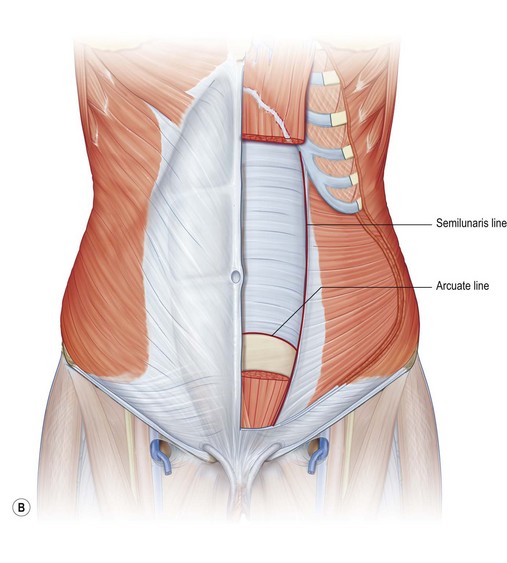

The skin of the abdomen has areas of increased adherence to the underlying fascia (“zones of adherence”), such as the anterior superior iliac crest and the linea alba. The abdominal subcutaneous tissue is divided by two layers of fascia, the superficial Camper’s fascia and the deep Scarpa’s fascia, a strong fibrous layer of connective tissue, which is continuous with the fascia lata of the thigh.19

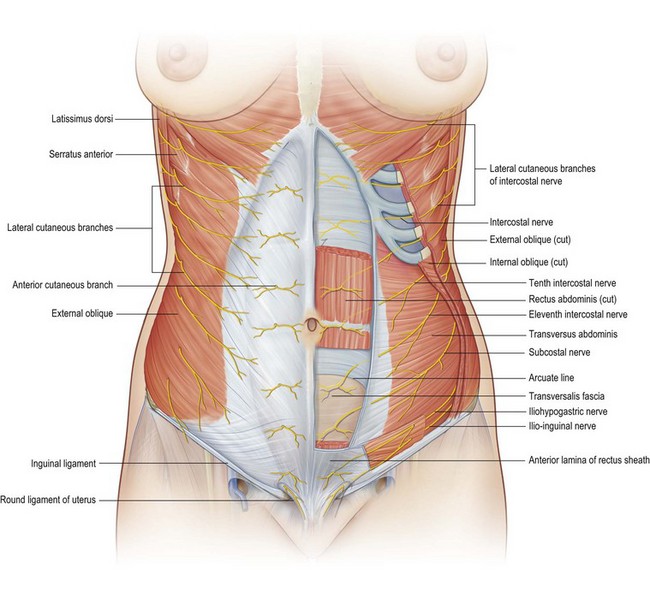

Since patients presenting for abdominal wall surgery often have musculoaponeurotic laxity, the knowledge of these anatomical structures is crucial. The abdominal musculature includes four paired muscles, which are the rectus abdominis, connected in the median linea alba, the external oblique and internal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscle, which incorporate into the anterior and posterior rectus sheath at the linea semilunaris. The rectus abdominis muscles are enclosed by an anterior and posterior sheath, originating at the infracostal margin and attaching at the symphysis pubis. Above the arcuate line (or semicircular line of Douglas, situated approximately midway between umbilicus and pubic symphysis), the anterior rectus sheath is formed by the external oblique and internal oblique aponeurosis, while the posterior rectus sheath is formed by the internal oblique and transversus aponeurosis. Below the arcuate line, the posterior rectus sheath is absent, except for the transversus fascia and the peritoneum, which are found posteriorly. At the inferior aspect of the rectus muscles, the pyramidalis muscles are present in 80–90% of patients (Fig. 25.3).

Lymphatic system

The lymph vessels collect the subdermal accumulated lymph fluid and drain into the deeper fat layer, passing into larger vessels. The abdominal lymphatic system is divided into supraumbilical drainage into the ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes and infraumbilical drainage into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. The lymph vessels in the infraumbilical area pass through the sub-scarpal plane, explaining the importance of Scarpa’s fascia preservation in abdominal wall surgery.18

Blood supply

The blood supply to the abdominal wall comes from numerous major arteries of the thorax and pelvic region, which communicate through many anastomotic interconnections. Taylor and Palmer introduced the concept of angiosomes, or vascular territories of the body.20 They describe two types of cutaneous blood supply: (1) direct vessels that directly supply the skin and (2) indirect vessels that “emerge from the deep fascia as terminal spent branches of arteries whose main purpose is to supply the muscles and other deep tissues.” In a subsequent study in 1988, Moon and Taylor were able to demonstrate connections between the deep superior and deep inferior epigastric systems and their relationship to the cutaneous circulation.21–23

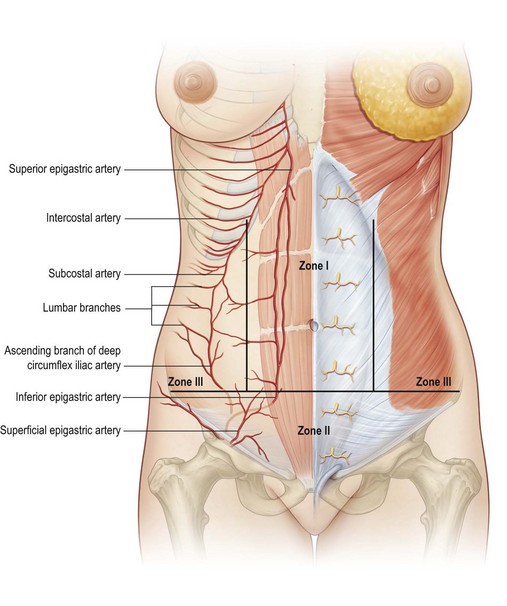

A detailed knowledge of the arterial supply of the abdominal wall is important for abdominal wall surgery, especially in cases of prior abdominal or chest wall surgeries. Huger described different zones of the abdominal blood supply, which should guide the surgeon in planning and performing a safe operation (Fig. 25.4).22 Huger defined zone I of the abdominal wall as the area that is fed anteriorly by the vertically oriented deep epigastric arcade. Zone III was defined as the lateral aspect of the abdominal wall (flanks) that are fed by the six lateral intercostal and four lumbar arteries. The lower abdominal circulation is provided by the superficial epigastric, superficial external pudendal, and superficial circumflex iliac systems (zone II). A rich plexus between these systems allows collateral flow.

Nerves

Cutaneous sensation of the abdominal wall is derived from the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the intercostal nerves 8–12, which pass between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, entering the rectus abdominis muscle and reaching the overlying fascia and skin. The lateral cutaneous branches penetrate the intercostal muscles in the midaxillary line, ending in the subcutaneous layer. Both branches are responsible for the overlapping of the sensory dermatomes T5–L1. The motor branches of the oblique and transversus abdominis muscle derive from lower thoracic and lumbar dorsal nerves, while the rectus abdominis muscle is innervated from branches of the intercostals nerves 5–12, which pass behind the rectus muscles and enter the muscles at the junction of the lateral one-third and medial two-thirds.23

As peripheral nerves with either motor nor sensory innervations to the abdominal wall, the iliohypogastric and iliohypogastric have to be mentioned, since their course can be disrupted in lateral transverse lower abdominal incisions, resulting in consistent loss of sensory in the area of the groin and medioventral thigh (Fig. 25.5).

Pathology

Pregnancy is the commonest cause of abdominal wall deformities because the skin and musculoaponeurotic structures are stretched beyond their biomechanical capability to retract. Consequently, there is thinning and loss of elasticity of the skin with possible striae and diastasis of the rectus muscles. Postpartum weight loss contributes to the process of abdominal wall deformities, because of limited skin retraction. Massive weight loss after dieting or bariatric surgery results in similar pathophysiologic changing of the abdominal wall, including excess skin and subcutaneous tissue and a laxity of the abdominal wall musculature. Increasing demand of these specific patients for abdominal wall restoration has extended the abdominal surgery to lower circumferential procedures. These problems are reviewed in Chapter 27 and 30.

Fat accumulation occurs in a distribution pattern that varies according to the gender. With weight gain, women tend to add local adiposity in the lower trunk and hip region, while men see an increase in abdominal girth. In women, fat accumulation commonly in the posterior thigh region can result in cellulite, induced by fibrous septa within the subcutaneous tissue.24

Congenital abdominal wall defects distant to the umbilicus are relatively uncommon and based on structural defects of the abdominal wall. Omphalocele, a defect in the group of persistent fetal ducts, resolve spontaneously in 80% of children within the first 12 months.25 Gastroschisis, one of the more common congenital abdominal wall defects, results in herniation of fetal abdominal viscera into the amniotic cavity, which has to be surgically corrected in most cases by primary closure or staged silo repair. A discussion of abdominal wall reconstruction appears in Volume IV, Chapter 12.

Classification of problems

In 1988, Bozola and colleagues published a classification including five different groups of aesthetic deformities of the abdomen with assigned operative procedures.26,27 Group I comprised younger nulliparous women with normal elastic skin and good muscle tone but excess adipose tissue in the subcutaneous layer in the abdominal area. Group II patients usually had at least one pregnancy, mild lower abdominal skin laxity, diastasis recti, and excess adipose tissue most often present inferior to the umbilicus. Group III includes patients with significant infraumbilical skin, excess adiposity, and abdominal muscle laxity with diastasis of the rectus and oblique muscles. In addition, patients often have striae after multiple pregnancies. Patients in group IV and V have severe skin and fat excess superior and inferior to the umbilicus, accompanied by mild to severe diastasis of the rectus and oblique muscles. Group V patients present with an umbilicus which is below the ideal height.

To attempt the correlation of appearance and physical examination findings to appropriate surgical interventions in patients after massive weight loss, Song et al. designed the “Pittsburgh Rating Scale”, a classification system that addresses the full range of post-weight loss deformities found in this unique population (Fig. 25.6).28

Patient selection and indication

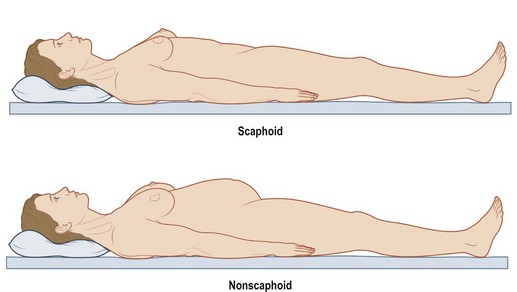

The preoperative evaluation of intra-abdominal content and the resulting pressure is important to avoid a postoperative pressure increase or abdominal compartment syndrome. In cases of elevated intra-abdominal pressure, in the supine position, the abdominal wall elevates above the costal margin and the level of the iliac crest (Fig. 25.7). Abdominoplasty procedures with or without rectus plication, have to be performed cautiously in such cases.

History and physical examination

The physical examination covers the entire abdominal wall, including the skin and fat layer, the musculoaponeurotic layer and the intra-abdominal volume. Examination of the skin and fat tissue is done by pinching and measurement of the subcutaneous layer thickness. Skin quality and the presence of striae are assessed, noting that supraumbilical striae commonly are not resected in abdominoplasties. Studies on skin quality in post-bariatric patients have demonstrated damage to collagen structures.29,30

The following documentation is recommended:

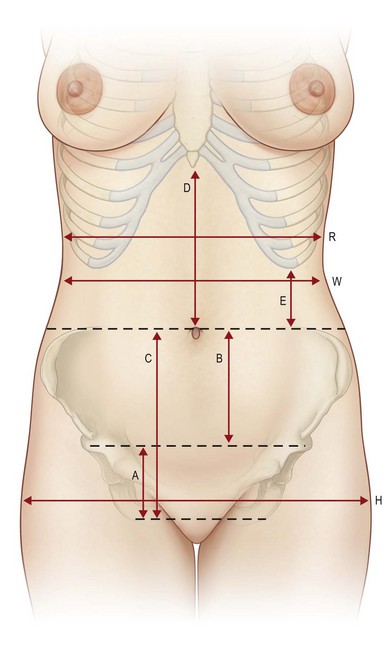

The following measurements are recommended:

• Distance from umbilicus to top of mons

• Distance from umbilicus to sternal notch

• Distance from anterior vulva commissure to top of mons

• Waist and hip measurement, waist-to-hip ratio

• Thickness of abdominal adipose tissue by pinching.

• Due to an increased risk of thromboembolism and seroma formation, indication for abdominal surgery should be made critical in cases of a BMI higher than 30 or an estimated weight of resection above 1500 g. Further, a higher preoperative BMI restricts the postoperative aesthetic results.

Aesthetic procedures

Markings and scar-position – measurements

We commence the marking with a partially dressed patient in the upright position in order to mark the borders of the underwear. The future scars should then be evaluated and discussed with the patient. In this context, it is important to inform the patient that tractive forces and tissue excess may cause asymmetric results and aberrant scar positions. We mark the future scar line with a different coloured felt pen. This procedure has proved its value, since the patient gets involved in the preoperative planning, and thus feels jointly responsible for the future scar course (Fig. 25.8).

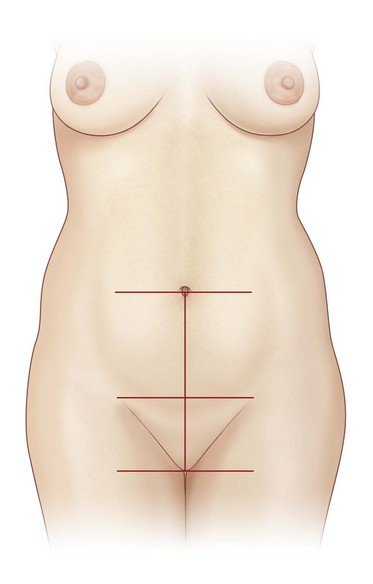

Fig. 25.8 Markings are to be performed with respect to the anterior vulva commissure and the umbilicus.

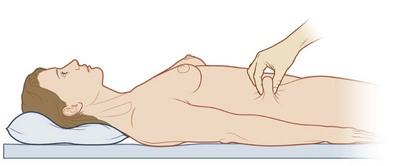

The expected resection is then evaluated by careful pinching of the tissue (Fig. 25.9). According to the physical equilibrium of forces, we mark the lower incision line about one to two finger-breadths below the expected scar line. The patient is asked to evaluate the redundant tissue for precise positioning.

The lower incision line will run parallel to the scar line and is normally 1–2 cm below the abdominal fold. It is essential to respect a minimum distance of 6–7 cm superior to the anterior vulva commissure. In cases of mons pubis hypertrophy or ptosis the lower incision line must be adapted (see Fig. 25.29).

Pre-, intra-, and postoperative management and general considerations

Preoperatively, patients should always be prewarmed by using convective warming devices immediately prior to surgery and active warming should be used in surgeries longer than 1 h. Numerous studies have shown a significant reduction of postoperative complaints and complications due to systemic warming.31

Wound closure

• For optimal wound closure, the patient has to be intraoperatively flexed at the level of the hips. As mentioned previously, this maneuver should be checked prior to preparation and draping.

• Larger wound cavities superior and inferior to the umbilicus may be reduced using progressive tension sutures, utilizing slow absorbable suture material. This is done to help prevent seroma formation.

• Wound closure is performed by reapproximation of each layer. It is recommended to insert drains before deep fascial closure. We usually prefer to insert one drain on each side.

• Continuity of the Scarpa’s fascia is achieved with slow absorbable sutures in a single knot or running technique. A new generation barbed suture may be used (in a running manner) for a shortened closure time and less tissue damage. The subdermal layer is closed using slow absorbable sutures in single knot or running technique or alternatively, using barbed sutures in a running technique. We facilitate a minimum of tension at the dermal layer by everting both wound edges; this helps to ensure optimal coaptation of the wound in order to avoid using intracuticular sutures. Nevertheless, for reasons of wound security, an intracuticular absorbable barbed suture can be used (Fig. 25.10). Alternatively, a two component wound closure device consisting of an adhesive mesh tape and new generation cyanoacrylate (PRINEO™, Ethicon Inc., Somerville NJ) has shown to be equally safe but faster than intradermal sutures in a multicenter study.32 We currently favor this closure system, since it reduces operating time, it acts as a germ barrier and is easily removable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree