Introduction

Diagnostic algorithm

Blistering as a manifestation of systemic illness

Age of onset

Family history

Distribution of blistering

Introduction

The approach to the child with vesiculobullous disease is a complicated and challenging task given the vast differential diagnosis as well as the great concern of both the referring practitioner and the child’s parents which occurs with these diseases. This chapter gives a general overview of the approach to infants and children with common vesiculobullous diseases, focusing on clinical features, and provides an algorithm for the differential diagnosis of these conditions. The reader is referred to other chapters for more detailed information on the diagnosis and management of these diseases.

Terminology.

Primary vesiculobullous skin lesions include vesicles, bullae or pustules (Table 87.1). Vesicles are small fluid-filled blisters less than 0.5 cm in diameter; bullae are fluid-filled blisters greater than 0.5 cm in diameter. Pustules, which are vesicles with a purulent exudate, may occur as a primary lesion, as in infantile acropustulosis and subcorneal pustular dermatosis, or may represent a secondary change in a bulla or vesicle. Vesicles over 48 hours old typically evolve to become pustules. Other secondary lesions include erosions and ulcers. Erosions occur as a consequence of loss of the superficial layers of the epidermis, leaving only a collarette of scale at the periphery as a clue to the primary lesion. Erosions such as these are often seen when a superficial blister ruptures (as in pemphigus vulgaris) or has been scratched (such as in dermatitis herpetiformis). In the absence of secondary infection, erosions and superficial blisters usually heal without scarring. Ulcers are secondary lesions that occur when the epidermis and superficial papillary dermis are lost, either as a consequence of the blistering process, such as in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, or as a result of secondary infection of a more superficial blistering process.

Table 87.1 Primary and secondary lesions in vesiculobullous disease

| Lesion | Description |

| Vesicle | Fluid-filled blister ≤0.5 cm in diameter |

| Bulla | Fluid-filled blister >0.5 cm in diameter |

| Pustule | Primary or secondary lesion; vesicle with a purulent exudate |

| Erosion | Secondary lesion due to partial loss of epidermis |

| Ulcer | Secondary lesion due to complete loss of epidermis |

| Milia | Firm, white 1–2 mm cysts which represent retention cysts |

Other clinical features that should be noted in evaluating a patient with a blistering process include scales, crust, milia and scarring. Scales, desiccated plates of keratin, are commonly found in superficial blistering processes such as pemphigus foliaceous. Crusts, a dried exudate composed of serum and cells, may be found overlying erosions or ulcers as in bullous impetigo or pemphigus vulgaris. Primary milia are firm white 1–2 mm cysts which are derived from the infundibulum of vellus hairs and are commonly found in neonates. Secondary milia represent retention cysts which occur as sequelae of subepidermal vesiculobullous diseases and are classically found in some porphyrias and epidermolysis bullosa. The presence of scarring suggests a blister at or below the basement membrane, although scarring can occur following secondary infection of an intraepidermal blister (e.g. secondary impetiginization of varicella).

Clinical Features.

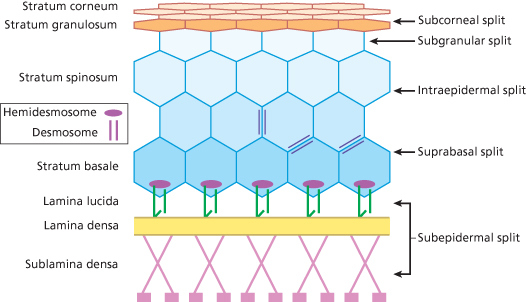

Early in the assessment of a child with a vesiculobullous disorder, one must assess the type of blister that has been created as this will give clues to the pathophysiology of the blister formation. For both vesicles and bullae, the traditional approach is to determine if the lesions are flaccid or tense bullae which equates to a split in the intraepidermal or subepidermal layer, respectively (Fig. 87.1). Intraepidermal blisters may arise in the granular, spinous or suprabasal layers of the skin (Box 87.1). Clinically, blistering within the epidermis presents as thin, flaccid blisters which rupture easily, leading to erosions, scale and crust. Exceptions to this rule are often related to body location. For example, friction blisters occur subcorneally but present as tense blisters due to the thick stratum corneum at acral sites. In contrast, intraoral blisters (both intraepidermal and subepidermal) usually present as erosions due to persistent oral trauma. Pigment changes and scarring are not common in intraepidermal blisters unless secondary infection occurs. Patients with widespread intraepidermal blisters may display the Asboe–Hansen and Nikolsky signs. These signs, respectively, refer to the ability to spread a blister into adjacent normal skin and the ability to induce a blister by rubbing normal-appearing skin. These signs are classically associated with pemphigus but may also be seen in patients with erythema multiforme (EM), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) or staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS).

Box 87.1 Cleavage plane for common blistering disorders

Subcorneal Blisters

- Infectious

- Bullous impetigo

- SSSS

- Candidiasis

- Dermatophytosis (tinea pedis)

- Bullous impetigo

- Mechanical

- Friction blisters

- Inflammatory

- Pustular psoriasis

- Subcorneal pustular dermatoses (Sneddon–Wilkinson)

- Pustular psoriasis

Intraepidermal Blisters

- Acute spongiotic dermatitis

- Allergic contact dermatitis

- Irritant dermatitis

- Atopic dermatitis

- Allergic contact dermatitis

- Infectious

- Viral

herpes simplex

varicella, herpes varicella zoster

hand–foot–mouth disease

- Viral

- Environmental

- Photo reactions

phototoxic (sunburn)

photo drug

- Burns (thermal or chemical)

- Photo reactions

- Genetic

- EBS

- Hailey–Hailey disease

- EBS

- Autoimmune

- Pemphigus vulgaris

- Pemphigus foliaceus

- Intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis

- Pemphigus vulgaris

Subepidermal Blisters

- Idiopathic

- EM

- Coma blisters

- EM

- Autoimmune

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Cicatricial pemphigoid

- EB acquisita

- Bullous lupus erythematosus

- Linear IgA dermatosis

- Dermatitis herpetiformis

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Inflammatory

- Mastocytosis

- Bites and stings

arthropod

fire ant

- Mastocytosis

- Genetic

- EB

junctional

dystrophic

- EB

EB, epidermolysis bullosa; EBS, epidermolysis bullosa simplex; EM, erythema multiforme; SSSS, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

In contrast, subepidermal blistering diseases typically present with tense bullae. Rupture of a subepidermal blister leaves a base devoid of pigmentation as melanocytes localize to the blister roof. The loss of pigment at the base of a subepidermal blister is more pronounced in darker-skinned patients. Depending on the disease subtype, the subepidermal blisters may or may not heal with scarring.

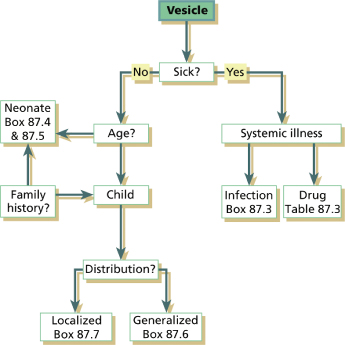

Diagnostic Algorithm

In approaching a child or infant who presents with a blistering process, the algorithm in Figure 87.2 may be useful in arriving at a clinical differential diagnosis. This algorithm is meant to serve as a guide to the more common causes of vesiculopustular diseases in infants and children and is not an exhaustive listing of all potential causes. Nevertheless, the general principles described here are useful in determining the appropriate category of disease and guiding the evaluation of the affected child. Subsequent chapters in this section contain detailed descriptions of a number of disorders considered as primary vesiculobullous diseases. Other conditions may also present with blisters. The reader is referred to these chapters for further description of the clinical signs and symptoms, diagnostic features and management of these conditions.

Key factors in the differential diagnosis of a child or infant with a vesiculobullous disease include (i) whether the vesiculobullous process is a manifestation of an underlying systemic illness; (ii) the age of onset; (iii) the family history; and (iv) the distribution, particularly whether the blisters are generalized or localized (Box 87.2). Other findings which may be helpful in arriving at a diagnosis include (i) the morphology of lesions (flaccid versus tense blisters); (ii) the presence of secondary changes; and (iii) the pattern of eruption (e.g. annular, serpiginous or grouped).

Box 87.2 Decision points in the differential diagnosis of vesiculopustular disease

Is the child/neonate sick?

Differential: infections, drug reaction, inflammatory condition

When did the blistering begin?

Blistering in neonatal period versus blistering in child

Is there a family history of blistering?

Differential: genodermatosis, autoimmune blistering or metabolic process

Is the blistering localized or diffuse?

Localized, e.g. phototoxic, photoallergic, physical/chemical agents, contact dermatitis, mastocytosis

Diffuse, e.g. miliaria, pustular psoriasis, Sneddon–Wilkinson disease, drug eruptions

Supplement clinical decision making with histopathology and ancillary testing.

In additional to the clinical differential diagnosis, when faced with a challenging vesiculobullous disease in a paediatric patient, often the clinical differential must be narrowed with the use of histology and ancillary testing. Ancillary testing in vesiculobullous disease may include the following: mineral oil preparation, Wright’s stain, viral cultures, Tzanck preparation, direct fluorescent antibody testing, polymerase chain reaction, Gram stain and bacterial cultures, KOH slide preparation and fungal cultures, standard histopathology with haematoxylin and eosin, direct immunofluorescence on skin biopsies, indirect immunofluorescence using the patient’s serum, immunofluorescence mapping, electron microscopy and genetic testing, Many of these methodologies are used on a regular basis, such as the bacterial and viral tests. However, others, such as the use of electron microscopy, are reserved for making the rare diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa and differentiating recessive versus dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa based on absent or decreased anchoring fibrils, respectively [1].

Reference

1 Yiasemides E, Walton J, Marr P et al. A comparative study between transmission electron microscopy and immunofluorescence mapping in the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Dermatopathol 2006;28:387–94.

Blistering As a Manifestation of Systemic Illness

The first decision point in evaluating a patient with blisters is to decide if the child is ill, surely one of the most important questions all doctors must ask in evaluating any patient. Of grave concern is the possibility that the blistering process is a manifestation of an underlying systemic illness which may progress rapidly without treatment. Among the systemic conditions which may present as vesiculobullous diseases and which must be considered in the differential diagnosis are infections, inflammatory reactions and drug eruptions. Fever, lethargy, decreased appetite or behaviour changes are important signs and symptoms of infection in children. However, these findings may be absent in neonates with sepsis. The presence of blisters in a neonate, despite the absence of other overt signs and symptoms of infection, must still raise the possibility of a life-threatening infection.

Infections include both cutaneous infections of bacteria, viruses and fungi as well as cutaneous response to a systemic infection. The bacterial infections in the neonatal period which may present with blisters, pustules or erosions include:

- Staphylococcus aureus, which may present as impetigo neonatorum or SSSS

- Streptococcus (particularly group A β-haemolytic streptococci)

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Listeria monocytogenes

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- Escherichia coli

- Treponema pallidum (Box 87.3).

Box 87.3 Infections associated with blistering

Viral

- Herpes (herpes simplex, herpes varicella zoster), cytomegalovirus,

- Epstein–Barr virus, coxsackievirus, poxvirus (variola, monkeypox)

Fungal

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree