Kawasaki disease (KD, mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome) is an acute systemic inflammatory illness with vasculitis that mainly affects infants and children less than 5 years of age. It has highest incidence in Japan but occurs worldwide, having been observed on all continents and in all ethnic groups. Although originally believed to be a benign illness, KD is now known to be associated with coronary artery aneurysms in about 25% of untreated cases; sequelae range from asymptomatic coronary artery dilation or aneurysm to giant coronary artery aneurysms with thrombosis, myocardial infarction and sudden death. KD is the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in developed countries.

Since the disease was first reported in 1967, significant advances have been made in its clinical, pathological and epidemiological characterization. However, the aetiology remains unknown. The recognition of late adverse events occurring even in those without detectable coronary abnormalities makes accurate diagnosis, treatment, and continued monitoring critical.

Epidemiology.

Kawasaki disease predominantly affects young children, with peak incidence at 6–12 months of age in Japan and at 1.5–2 years of age in the United States and European countries [1]. Nearly 85% of all cases occur between 6 months and 5 years of age. The rarity in the first few months of life and after early childhood suggests that transplacental antibodies from the mother may protect the neonate from disease and that widespread immunity develops over time. Males are more often affected (1.4:1) [1,2].

Asian children, especially those of Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese descent, have the highest incidence of KD (respective rates of 218, 113, and 69 per 100,000 children under 5 years of age) [3–5]. In the United States, African-Americans and Hispanics show intermediate incidence and Caucasians have the lowest rate of illness (12 per 100,000 children) [6]. The greatly increased frequency of KD in children of Asian ethnicity holds true for children who are living a western lifestyle after migration to other countries, supporting a genetic predisposition for disease. Cases occur year-round, but there are mini-epidemics and a seasonal peak of KD during the winter and spring months and again in mid-summer [3,7]. The incidence has been gradually rising in developed countries including Japan and the United Kingdom, and more rapidly in developing countries such as India, although this may stem from increased recognition [8].

Person-to-person transmission appears unlikely as secondary cases rarely occur in the same household, school or daycare facility. The recurrence rate is reported at 3–4% based on data from Japan and is highest within the first 12 months after the first episode. The fatality rate is now estimated at 0.01% in the latest national survey in Japan [9].

Pathogenesis and Theories of Aetiology.

The disease is characterized by marked activation of the immune system, with increased serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1, IL-4 and IL-6 during the acute febrile phase. Neutrophils are the predominant inflammatory cell type in the peripheral blood but in affected tissues, early infiltration by neutrophils is followed by mononuclear cells, lymphocytes, macrophages and plasma cells [1,10]. CD8 T-lymphocyte and B-lymphocyte proliferation occur and indicate an adaptive immune response. Oligoclonal IgA plasma cells have been found infiltrating the coronary arteries, pancreas, kidney and upper respiratory tract [2,10].

What causes KD remains an enigma but epidemiological data suggest that it is due to one or more widely distributed infectious agents triggering an abnormal immunological response in a small subset of individuals genetically predisposed for the illness.

A genetic influence has been long suspected given that children born to parents with a history of KD are twice as likely to develop disease, siblings of affected children have 10–20 times increased likelihood of disease development, and Asian children have high rates of disease independent of geographic location [11]. Genetic variation in the chemokine receptors 2, 3 and 5 (CCR2, CCR3, CCR5) has shown consistent association with KD susceptibility. Polymorphisms in several matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) genes and the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate 3-kinase C ( ITPKC) gene involved in T-cell activation appear not only to increase susceptibility to developing KD, but also increase the tendency for development of coronary artery lesions [12,13]. A recent genome-wide association study in a predominantly Caucasian population identified additional candidate genes related to inflammation, apoptosis and cardiovascular pathology [14]. The molecular genetics of KD is an emerging field and like other inflammatory illnesses, appears to be genetically complex, with multiple genes contributing to overall susceptibility.

Despite the seasonality, temporal clustering of cases and usually self-limited course suggestive of an infectious aetiology, no clear agent or environmental trigger has been found. KD shares some clinical features with scarlet fever and toxic shock syndrome, diseases known to be mediated by bacterial toxins acting as superantigens. Similar activation of monocytes/macrophages and expansion of T-lymphocytes, particularly ones expressing specific T-cell receptor (TCR) β chain variable gene regions, have been noted by some but this remains controversial [15]. Antibodies to these toxins (i.e. staphyloccocal enterotoxins, streptococcal pyogenic exotoxins and toxic shock syndrome toxin type 1) and toxin-producing bacteria have not been consistently detected at higher levels in the peripheral blood of KD patients relative to controls [16,17].

Others have used synthetic antibodies derived from prevalent IgA antibody sequences in acute KD arterial tissue and have demonstrated an antigen in the cytoplasm of bronchial epithelial cells and a subset of macrophages. Light and electron microscopic studies localized the antigen to intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies consistent with aggregates of viral proteins and nucleic acids. This suggests a conventional antigen from an unidentified RNA virus playing an important role in KD aetiology [18]. Investigations are ongoing for a virus that may have a respiratory portal of entry and tropism for vascular tissue.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis.

The diagnosis of KD is established by the presence of six principal features. The most widely used criteria require fever of at least 5 days’ duration and at least four of the five other clinical findings, although diagnosis and treatment can occur before day 5 of fever if the other four findings are already present [19] (Box 168.1) In Japan, fever is used as one criterion, rather than as a prerequisite symptom.

1 Fever of unknown aetiology persisting for 5 days or more. In general, the patient has remittent or continuous fever of sudden onset and frequent spikes (39–40°C), without prodromal symptoms such as cough, sneezing or rhinorrhea. The duration of fever is usually 1–2 weeks in untreated patients. The longer the fever continues, the higher the possibility of coronary artery aneurysm development, and severe lesions are likely to remain if fever continues for 10 days or longer. The fever does not respond to oral antibiotics or antipyretics, but subsides more rapidly when IVIG is administered with aspirin compared with therapy with aspirin alone [20].

Box 168.1 Diagnostic Guidelines for Kawasaki Disease

- Fever persisting for at least 5 days AND

- Changes in peripheral extremities:

- Initial stage: reddening of palms and soles, indurative oedema

- Convalescent stage: membranous desquamation from fingertips

- Initial stage: reddening of palms and soles, indurative oedema

- Polymorphous exanthem

- Bilateral conjunctival injection

- Changes in the lips and oral cavity: reddening of lips, strawberry tongue, diffuse injection of oral and pharnygeal mucosa

- Acute non-purulent cervical lymphadenopathy

Fever and at least four of five principal symptoms should be satisfied for the diagnosis of classic KD. However, patients with fewer than four of the principal symptoms can be diagnosed as having KD when coronary aneurysm is recognized by two-dimensional echocardiography or coronary angiography.

2 Changes in peripheral extremities. The findings on the hands and feet in KD are distinctive. Within the first week after fever onset, erythema of the palms and soles (Fig. 168.1) and/or indurative oedema of the dorsum of the hands and feet (Fig. 168.2) occur. There may be a fusiform swelling of the digits with frank arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joints, and associated tenderness can be severe enough to limit walking or use of the hands [21]. After the fever subsides, the erythema and swelling disappear in most cases. About 10–15 days after the onset of illness, there is fissuring between the nails and the tips of the fingers and toes (Fig. 168.3), after which membranous desquamation spreads proximally, often peeling in large thick pieces.

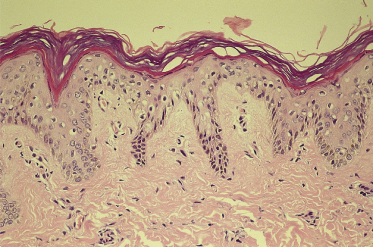

3 Polymorphous skin eruption. During the first week after the onset of fever, an exanthem (Fig. 168.4) usually appears on the trunk and/or proximal extremities. Perineal involvement is common (about two-thirds of cases), ranging from confluent macules to a plaque-type erythema. Perineal desquamation may occur during the acute febrile phase and precedes the desquamation on the hands and feet. The more generalized eruption can be of many forms: an urticarial eruption with large erythematous plaques, a scarlatiniform or morbilliform rash or, in rare cases, erythema multiforme-like with central clearing or iris lesions. Each lesion becomes increasingly large, and often lesions coalesce. Vesicle or bullae are unusual; however, about 5% of patients show small aseptic micropustules on the knees, buttocks or other body sites (Fig. 168.5). Histologically, the lesions have non-specific findings that include marked oedema of dermal papillae, focal intercellular oedema of the basal cell layer and very slight perivascular infiltration of mononuclear cells in the papillary dermis, with the dilation of small vessels (Fig. 168.6).

Fig. 168.6 Skin histology from an erythematous patch of the exanthem, showing a sparse mononuclear cell infiltrate in the papillary dermis around small dilated blood vessels.

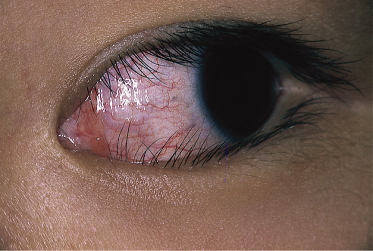

4 Bilateral conjunctival injection. Within 2–4 days of disease onset, injection of the ocular conjunctiva develops (Fig. 168.7). It is non-purulent and often shows limbic sparing. Each dilated capillary is clearly seen. Careful slit-lamp examination early in the course of the disease may reveal anterior uveitis. The conjunctival injection usually subsides within 1–2 weeks but sometimes continues for more than a few weeks. Anterior uveitis follows a similar course and has few sequelae in KD, unlike with many other infectious causes of uveitis [22]. With IVIG treatment, injection may improve quickly following treatment. Other ocular findings include iridocyclitis, superficial punctate keratitis, vitreous opacities, papilloedema and subconjunctival haemorrhage.

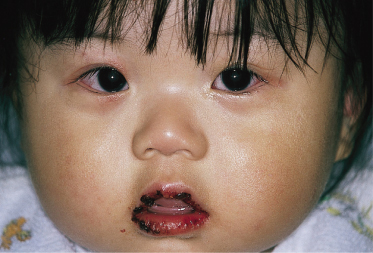

5 Changes in lips and oral cavity. Changes in the lips and oral cavity are characterized by redness, dryness, fissuring, peeling and bleeding of the lips, diffuse erythema of the oropharyngeal mucosa, and strawberry tongue without pseudo-membrane formation. Aphthae and ulcerations of the oral mucosa are not seen. Redness of the lips may often continue for 2–3 weeks after the disappearance of other symptoms. Bilateral injection of the eyes together with the changes in the lips combine to give the characteristic appearance of KD and can be an important aid to diagnosis (Fig. 168.8).

Fig. 168.8 Typical appearance of acute KD: redness, dryness and bleeding of the lips with bilateral conjunctival hyperaemia.

6 Acute non-purulent cervical adenopathy. Approximately one-third of patients develop a single firm, non-fluctuant and painful mass, ranging from 1.5 to 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 168.9). Involvement occasionally may be bilateral and be misdiagnosed as mumps. In some older patients cervical lymph node adenopathy is the most striking clinical symptom of KD, appearing 1 day before the onset of fever or together with fever, but in the absence of other clinical signs.

In addition to these classic findings, the affected child appears ill and is often very irritable, much more than with other febrile illnesses. About one-third, however, present with lethargy instead. Neck stiffness and aseptic meningitis can occur, with the CSF showing mild mononuclear cell pleocytosis but normal glucose and protein. Less frequently, patients develop transient unilateral facial palsy or high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss. Urethritis and sterile pyuria occur in 33–79% of patients [23]. Gastrointestinal findings include diarrhoea, vomiting and abdominal pain. In addition, hepatic enlargement, acute distension of the gallbladder, jaundice and transient elevation in the serum transaminases and γ-glutamyl-transpeptidases may be seen [24]. Diffuse arthralgias that involve multiple joints, both large and small, can occur early in the illness. Later arthralgias and arthritis tend to favour the large weight-bearing joints [25].

The clinical course of KD is generally divided into three phases. The acute phase lasts 7–14 days and is characterized by fever, the mucocutaneous changes and other acute signs of illness described above. The dominant cardiac manifestation is myocarditis. In addition, a macrophage activation syndrome may rarely be evident [26]. The subacute phase (day 10–25) begins when fever and other acute signs have abated, but irritability, anorexia, arthralgias and conjunctival injection may persist. It is in this phase that desquamation, thrombocytosis and the development of coronary aneurysms occur. The risk of sudden death in those who have developed aneurysms is highest during this period. The convalescent phase begins around day 20 when all clinical signs of illness have disappeared and continues until the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) return to normal, approximately 6–8 weeks after the onset of illness. In patients with previously normal echocardiograms, development of aneurysms is unusual after week 8 of the illness [19]. However, for those who do develop cardiovascular abnormalities, a fourth chronic phase of lifetime significance may be identified, where there is risk for complications extending into adulthood.

Other Cutaneous Findings

A unique feature of KD is acute inflammation at the site of prior bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination. This may be localized erythema, peeling/crusting or even a bullous lesion that can become an ulcer [27–29]. The reaction may be secondary to cross-reactivity between specific epitopes of mycobacterial and human heat shock proteins [30]. Studies from Taiwan suggest a significant association between reactivation of inflammation at the BCG vaccination site and a functional polymorphism in ITPKC gene that modulates T-cell activation [12,31].

The subacute and convalescent phases of KD may be complicated by the first episode of atopic dermatitis in patients with no previous history of this condition. Frequently, there is a family history of atopic dermatitis and/or personal history of other atopic conditions and it has been postulated that the intense activation of the immune system associated with acute KD precipitates the first appearance of this chronic skin condition in a genetically susceptible host [32,33].

Psoriasiform eruptions have been described in the acute and convalescent phases of KD. This includes plaque, guttate and pustular lesions. In one retrospective study of 476 children with KD, nine (1.9%) were affected, similar to the rate of psoriasis expected in the general adult population but higher than that in the general paediatric population [34]. Two of the children had a family history of psoriasis. A recent more refractory case of KD showed psoriasiform papules and plaques on the extensor extremities along with crusted hyperkeratotic papules at the tips of the digits following treatment with IVIG, aspirin, methlyprednisolone and infliximab [35]. It is unclear if this may have any relationship to therapy or if the eruption could have been modulated given treatment with infliximab, a chimeric antibody also used to treat psoriasis. Also unclear is whether the co-occurrence of psoriasiform lesions and KD reflects activation of latent psoriasis in genetically predisposed individuals or a common aetiological agent for both KD and psoriasis. The psoriasiform eruption usually lasts several weeks to months and thus far, no cases associated with KD have been reported to become chronic psoriasis [34,36].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree