Erythema nodosum

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa

Superficial thrombophlebitis

Cold panniculitis

Post-steroid panniculitis

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn

Sclerema neonatorum

Panniculitis associated with connective tissue diseases

Lupus panniculitis (lupus erythematosus profundus)

Panniculitis in dermatomyositis

Lipodystrophy and lipoatrophy*

Pancreatic panniculitis

α1-Antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis

Calciphylaxis

Infective panniculitis

Factitial, iatrogenic or traumatic panniculitis

Sclerosing panniculitis (lipodermatosclerosis)†

Cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

Erythema induratum of Bazin (nodular vasculitis)

Erythema nodosum leprosum‡

Modified from Requena and Yus 2001 [1].

*Lipodystrophy and lipoatrophy are discussed in Chapter 141.

† Sclerosing panniculitis occurs primarily in middle-aged or elderly patients with chronic venous insufficiency of the lower extremities [3].

‡ Erythema nodosum leprosum is immune complex-mediated cutaneous small vessel vasculitis that is a type II reaction seen in leprosy patients usually undergoing treatment. While exceedingly rare, erythema nodosum leprosum does occur in children and may precede the diagnosis of leprosy [8].

Confusion in terminology adds to the diagnostic difficulty of panniculitides. For example, historically, the terms Weber–Christian disease and idiopathic nodular panniculitis were used to refer to relapsing panniculitis with systemic symptoms, but most consider the terms obsolete as previously reported cases can often be reclassified into more specific entities including cytophagic panniculitis, erythema nodosum and facticial/traumatic panniculitis [3,4]. Rothmann–Makai syndrome (lipogranulomatosis subcutanea) was considered a variant of Weber–Christian disease without systemic symptoms, and while the term has been abandoned by most [3,5], it can still rarely be found in the literature [6]. Eosinophilic panniculitis refers to a predominance of eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate, and is generally considered a non-specific reaction pattern associated with various disorders (erythema nodosum, arthropod bites, drug injections, parasitic infections, eosinophilic cellulitis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and eosinophilic leukaemia) rather than a distinct entity [3,7].

Numerous processes that usually involve the dermis may also involve the subcutaneous fat, sometimes as the primary site of involvement. Examples include deep morphoea/scleroderma, granuloma annulare, rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, gout, Sweet syndrome and sarcoidosis; these entities will be discussed in more detail in other chapters of this text. In addition, lipoatrophies and lipodystrophies are sometimes classified under panniculitides, but will be discussed in Chapter 141. In this chapter we will confine our discussion to the panniculitides that have been reported to occur in childhood.

References

1 Requena L, Yus ES. Panniculitis. Part I. Mostly septal panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:163–83.

2 Diaz Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W. Panniculitis: definition of terms and diagnostic strategy. Am J Dermatopathol 2000;22:530–49.

3 Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Panniculitis. Part II. Mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:325–61.

4 White JW Jr, Winkelmann RK. Weber-Christian panniculitis: a review of 30 cases with this diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39:56–62.

5 Winkelmann RK, McEvoy MT, Peters MS. Lipophagic panniculitis of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;21:971–8.

6 Asano Y, Idezuki T, Igarashi A. A case of Rothmann-Makai panniculitis successfully treated with tetracycline. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31:365–7.

7 Adame J, Cohen PR. Eosinophilic panniculitis: diagnostic considerations and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:229–34.

8 Pandhi D, Mehta S, Agrawal S, Singal A. Erythema nodosum leprosum necroticans in a child – an unusual manifestation. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 2005;73:122–6.

Erythema Nodosum

Definition.

The most common form of panniculitis in both children and adults is erythema nodosum, with a peak incidence in the third decade of life. There have been many reported causes of erythema nodosum, but a significant number of cases remain idiopathic. The classic presentation is symmetrical, tender, erythematous nodules and plaques on the anterior lower legs that evolve into bruise-like lesions and heal without scarring. Histopathologically, erythema nodosum is the prototypical septal panniculitis without true vasculitis. Treatment is directed at the underlying disorder, if one is identified, or to relieve symptoms associated with the disorder.

Epidemiology.

The true incidence of erythema nodosum is unknown. In a retrospective review of the histopathology of 329 cases of panniculitis, erythema nodosum was by far the most common diagnosis (29%) [1]. That study did not analyse the age distribution, but in a review of 129 cases of erythema nodosum, fewer than 8% of patients were younger than 15 years, and the overall mean age was 31 years [2]. While erythema nodosum is the most common form of panniculitis in children, it remains more common in adults.

Reviews of erythema nodosum in adults have shown a strong predominance in females [2,3], but studies in children have found a more equal gender distribution in prepubertal children [4–8]. A retrospective review on a large cohort of children with Crohn disease found that girls were significantly more likely than boys to develop erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum [9].

Erythema nodosum is not limited to any racial or geographical distribution, but there is variation in the prevalence of aetiological factors.

Aetiology.

There are numerous reported potential aetiologies of erythema nodosum, including infections, drugs, systemic diseases such as Crohn disease and other miscellaneous conditions. Historically, tuberculosis was the most common aetiological factor in children with erythema nodosum [10], although by the 1960s streptococcal infection was an increasingly important cause [11]. There have been several relatively recent retrospective reviews of erythema nodosum in children, in which the most commonly associated condition was streptococcal infection [4,5,7,8]. In the only prospective study of erythema nodosum in children, conducted in Greece, infectious aetiologies were found in over 70% of patients, with almost half of all cases associated with β-haemolytic streptococcal infections [6]. Non-infectious aetiologies including sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease and drugs are less common causes of erythema nodosum in children than adults [12], but must still be considered. Malignancy, most notably Hodgkin lymphoma, has been rarely associated with erythema nodosum, both in children and adults [6,13]. Reported aetiologies of erythema nodosum in children are listed in Table 77.2.

Table 77.2 Potential causes of erythema nodosum in childhood [4–8,21–26]

| Idiopathic | |

| Infectious | β-Haemolytic streptococcus, usually pharyngitis Non-streptococcal respiratory infections Yersinia, Salmonella or Campylobacter gastroenteritis Pneumonia (Mycoplasma or Chlamydia) Cat-scratch disease Tuberculosis or other mycobacterium* Tularaemia Leptospirosis Epstein–Barr virus Parvovirus Dermatophytosis (e.g. kerion) Histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis or blastomycosis |

| Inflammatory diseases | Crohn disease Ulcerative colitis Sarcoidosis Behçet disease† Ankylosing spondylitis Acne fulminans |

| Drugs/immunizations | Oral contraceptive pills‡ Antibiotics (e.g. penicillins, sulphonamides)‡ Amfepramone (anorexigenic) BCG vaccination |

| Malignancy | Leukaemia Hodgkin lymphoma Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

*Erythema nodosum leprosum is a different disease that is a form of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis and is a type II reaction seen in leprosy patients undergoing treatment.

† The histopathology of erythema nodosum-like lesions associated with Behçet disease may be distinct from the findings in classic erythema nodosum [15].

‡ Reported primarily in adults [32–34].

Close to 50% of children with Behçet disease can present with lesions that clinically resemble erythema nodosum [14]. A recent report found that the histopathology of erythema nodosum-like lesions in Behçet disease usually shows lobular or mixed panniculitis with leukocytoclastic or lymphocytic vasculitis, distinct from the findings in classic erythema nodosum [15]. A previous study of such lesions suggested that a spectrum of histopathological findings can be found, including septal, lobular or mixed panniculitis, and found lymphocytic vasculitis in only 40% of cases [16].

Of note, there have been several reports of plantar erythema nodosum in children [17–20]. Cases such as these are now usually classified under the term palmoplantar eccrine hidradenitis, an entity of unclear pathogenesis but often associated with vigorous physical activity, trauma and/or hyperhidrosis. Despite the wide range of potential associated aetiologies, no specific cause can be identified in up to one-third of cases of childhood erythema nodosum [4].

Pathogenesis.

Erythema nodosum is generally thought to represent a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to the many and varied stimuli that have been associated with the condition. Potential roles for proinflammatory cytokines [35], reactive oxygen intermediates [36], and circulating immune complexes [29,37,38] have been proposed but have yet to be clearly elucidated. While it has been suggested that the shins have unique vascular anatomy and susceptibility to trauma, the reason for a predilection for erythema nodosum lesions at this site remains unclear [39].

Clinical Features.

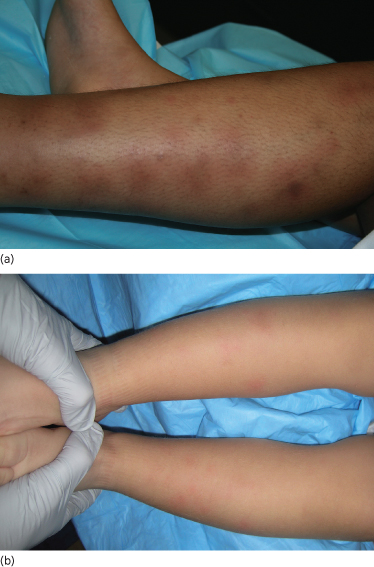

Erythema nodosum often presents with the sudden onset of tender, erythematous nodules and plaques symmetrically distributed on the shins, knees and ankles (Fig. 77.1). Less commonly the lesions can appear on the arms, thighs or face. The lesions fade to a bruise-like appearance before resolving completely within 2–6 weeks. The nodules and plaques do not ulcerate and heal without scarring. Recurrence may be less common in children than adults, and is seen more often in patients with an underlying chronic condition such as sarcoidosis or Crohn disease [5,6]. Patients with erythema nodosum may have preceding or associated systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, arthralgias, headache, upper respiratory symptoms, abdominal pain, vomiting, or diarrhoea, although again, these may be less frequent in children [6].

Fig. 77.1 Erythema nodosum. (a) A 13-year-old girl with tender erythematous nodules on her lower extremities. (b) A 2-year-old child with erythematous nodules located on the lower extremities associated with a neck abscess.

Clinical variants of erythema nodosum have been described mainly in adults, including chronic erythema nodosum, erythema nodosum migrans, and subacute nodular migratory panniculitis. While there is some debate in the literature, these entities are generally included within a spectrum of erythema nodosum and characterized by lesions that expand centrifugally with central clearing [12,40,41].

Histopathology.

Septal panniculitis without vasculitis is the hallmark histopathological feature of erythema nodosum. There is inflammation and thickening of the fibrous septa of the subcutaneous fat. The inflammatory infiltrate varies with the stage of the lesion, ranging from neutrophils in early lesions to lymphoctyes, giant cells and granulation tissue in late-stage lesions. Miescher radial granulomas are composed of histiocytes distributed in a rosette-like fashion around a central cleft, and are considered a classic feature in erythema nodosum, but can be seen in other conditions such as erythema induratum or necrobiosis lipoidica [15]. Late-stage lesions may have fibrotic septa with inflammation spilling over into the lobules, making diagnosis more difficult [39].

Investigations.

The diagnosis of erythema nodosum can often be made on a clinical basis, but a skin biopsy may be performed to confirm the diagnosis or if atypical clinical features are present. Given the extensive list of possible aetiological factors, the need to perform additional studies should be dictated by pertinent findings of a thorough history and physical examination (Table 77.3).

Table 77.3 Potential work-up for children with erythema nodosum of unknown aetiology

| Initial evaluation | History and physical examination Skin biopsy if needed to confirm diagnosis Complete blood count with differential Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) C-reactive protein Liver function tests Throat culture +/− rapid streptococcal antigen test Antistreptolysin O titre Tuberculin skin test* Chest X-ray |

| Additional studies to consider as indicated | Serologies for prevalent or endemic bacterial, viral, fungal or protozoal infections Stool culture for Yersinia, Salmonella or Campylobacter Inflammatory bowel disease panel (ASCA IgA, ASCA IgG, anti-OmpC, anti-CBlr1, IBD-specific pANCA) Serum immunoglobulins |

*Patients with erythema nodosum and a positive tuberculin skin test do not always have evidence of active underlying tuberculosis [35].

Differential Diagnosis.

The characteristic location and lack of ulceration can help to distinguish erythema nodosum from the other panniculitides, such as nodular vasculitis or polyarteritis nodosa, which will be reviewed later in this chapter. When the clinical findings are not diagnostic, erythema nodosum can usually be differentiated based on histopathology. As discussed above, Behçet disease can present with erythema nodosum-like lesions, but the diagnosis should be made based on associated symptoms that meet the criteria for diagnosis of Behçet disease [42]. Familial Mediterranean fever is characterized by erysipelas-like lesions on the lower legs that may be mistaken for erythema nodosum, but the episodic nature, associated symptoms, family history and histopathology are distinctive [43]. Rarely, other entities such as leukocytoclastic vasculitis (including Henoch–Schönlein purpura), deep granuloma annulare, eosinophilic cellulitis, leukaemia or child abuse can be clinically confused with erythema nodosum [6,7].

Treatment.

When an associated or underlying condition is identified, treatment should be directed at that condition. In mild cases, bed rest may be sufficient to result in spontaneous resolution of the lesions. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are often used to decrease inflammation and pain. Systemic steroids should only be used once an underlying infection has been ruled out. Potassium iodide is used to treat adults with erythema nodosum and other inflammatory dermatoses, but its use in children is limited by its potential side-effects [44].

References

1 Diaz Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W. Panniculitis: definition of terms and diagnostic strategy. Am J Dermatopathol 2000;22:530–49.

2 Cribier B, Caille A, Heid E, Grosshans E. Erythema nodosum and associated diseases. A study of 129 cases. Int J Dermatol 1998;37:667–72.

3 Tay YK. Erythema nodosum in Singapore. Clin Exp Dermatol 2000;25:377–80.

4 Garty BZ, Poznanski O. Erythema nodosum in Israeli children. Isr Med Assoc J 2000;2:145–6.

5 Hassink RI, Pasquinelli-Egli CE, Jacomella V, Laux-End R, Bianchetti MG. Conditions currently associated with erythema nodosum in Swiss children. Eur J Pediatr 1997;156:851–3.

6 Kakourou T, Drosatou P, Psychou F, Aroni K, Nicolaidou P. Erythema nodosum in children: a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44;17–21.

7 Labbe L, Perel Y, Maleville J, Taieb A. Erythema nodosum in children: a study of 27 patients. Pediatr Dermatol 1996;13:447–50.

8 Picco P, Gattorno M, Vignola S et al. Clinical and biological characteristics of immunopathological disease-related erythema nodosum in children. Scand J Rheumatol 1999;28:27–32.

9 Gupta N, Bostrom AG, Kirschner BS et al. Gender differences in presentation and course of disease in pediatric patients with Crohn disease. Pediatrics 2007;120:e1418–25.

10 Doxiadis SA. Aetiology of erythema nodosum in children. Br Med J 1949;2:844.

11 Laurance B, Stone DGH, Philpott MG et al. Aetiology of erythema nodosum in children. A study by a group of paediatricians. Lancet 1961;ii:14–16.

12 Requena L, Yus ES. Panniculitis. Part I. Mostly septal panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:163–83.

13 Bonci A, Di Lernia V, Merli F, Lo Scocco G. Erythema nodosum and Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol 2001;26:408–11.

14 Kone-Paut I, Yurdakul S, Bahabri SA et al. Clinical features of Behcet’s disease in children: an international collaborative study o 86 cases. J Pediatr 1998;132:721–5.

15 Kim B, LeBoit PE. Histopathologic features of erythema nodosum-like lesions in Behcet disease: a comparison with erythema nodosum focusing on the role of vasculitis. Am J Dermatopathol 2000;22:379–90.

16 Chun SI, Su WP, Lee S, Rogers RS 3rd. Erythema nodosum-like lesions in Behcet’s syndrome: a histopathologic study of 30 cases. J Cutan Pathol 1989;16:259–65.

17 Suarez SM, Paller AS. Plantar erythema nodosum: cases in two children. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:1064–5.

18 Berger TG, Tappero J. Traumatic plantar urticaria or plantar erythema nodosum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;20:701–2.

19 Hern AE, Shwayder TA. Unilateral plantar erythema nodosum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26:259–60.

20 Ohtake N, Kawamura T, Akiyama C, Furue M, Tamaki K. Unilateral plantar erythema nodosum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:654–5.

21 Garty B. Swimming pool granuloma associated with erythema nodosum. Cutis 1991;47:314–16.

22 Erntell M, Ljunggren K, Gadd T, Persson K. Erythema nodosum – a manifestation of Chlamydia pneumoniae (strain TWAR) infection. Scand J Infect Dis 1989;21:693–6.

23 Ozols, II, Wheat LJ. Erythema nodosum in an epidemic of histoplasmosis in Indianapolis. Arch Dermatol 1981;117:709–12.

24 Martinez-Roig A, Llorens-Terol J, Torres JM. Erythema nodosum and kerion of the scalp. Am J Dis Child 1982;136:440–2.

25 Kellett JK, Beck MH, Chalmers RJ. Erythema nodosum and circulating immune complexes in acne fulminans after treatment with isotretinoin. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:820.

26 Reizis Z, Trattner A, Hodak E, David M, Sandbank M. Acne fulminans with hepatosplenomegaly and erythema nodosum migrans. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:886–8.

27 Moraes AJ, Soares PM, Zapata AL, Lotito AP, Sallum AM, Silva CA. Panniculitis in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Int 2006;48:48–53.

28 La Spina M, Russo G. Presentation of childhood acute myeloid leukemia with erythema nodosum. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4011–12.

29 Akdis AC, Kilicturgay K, Helvaci S, Mistik R, Oral B. Immunological evaluation of erythema nodosum in tularaemia. Br J Dermatol 1993;129:275–9.

30 Sota Busselo I, Onate Vergara E, Perez-Yarza EG, Lopez Palma F, Ruiz Benito A, Albisu Andrade Y. [Erythema nodosum: etiological changes in the last two decades]. An Pediatr (Barc) 2004;61:403–7.

31 Modgil G, Bridges S. Erythema nodosum associated with Shigella colitis in a 7-year-old boy. Int J Infect Dis 2007;11:556–7.

32 Psychos DN, Voulgari PV, Skopouli FN, Drosos AA, Moutsopoulos HM. Erythema nodosum: the underlying conditions. Clin Rheumatol 2000;19:212–16.

33 Salvatore MA, Lynch PJ. Erythema nodosum, estrogens, and pregnancy. Arch Dermatol 1980;116:557–8.

34 Requena L, Yus ES. Erythema nodosum. Dermatol Clin 2008;26:425–38, v.

35 Nicol MP, Kampmann B, Lawrence P et al. Enhanced anti-mycobacterial immunity in children with erythema nodosum and a positive tuberculin skin test. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:2152–7.

36 Kunz M, Beutel S, Brocker E. Leucocyte activation in erythema nodosum. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:396–401.

37 Hedfors E, Norberg R. Evidence for circulating immune complexes in sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Immunol 1974;16:493–6.

38 Jones JV, Cumming RH, Asplin CM. Evidence for circulating immune complexes in erythema nodosum and early sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1976;278:212–19.

39 Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Erythema nodosum. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2007;26:114–25.

40 de Almeida Prestes C, Winkelmann RK, Su WP. Septal granulomatous panniculitis: comparison of the pathology of erythema nodosum migrans (migratory panniculitis) and chronic erythema nodosum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:477–83.

41 Lee UH, Yang JH, Chun DK, Choi JC. Erythema nodosum migrans. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005;19:519–20.

42 International Study Group for Behcet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behcet’s disease. Lancet 1990;335:1078–80.

43 Farasat S, Aksentijevich I, Toro JR. Autoinflammatory diseases: clinical and genetic advances. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:392–402.

44 Sterling JB, Heymann WR. Potassium iodide in dermatology: a 19th century drug for the 21st century – uses, pharmacology, adverse effects, and contraindications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:691–7.

Cutaneous Polyarteritis Nodosa

Definition.

Polyarteritis nodosa is a necrotizing vasculitis involving small- and medium-sized arteries that can affect any organ, and is rare in children. While patients with systemic polyarteritis nodosa can have skin involvement, there is a cutaneous form without significant systemic disease, and it has been debated whether the systemic and cutaneous forms should be considered distinct entities or form a spectrum of one disease [1–3].

Aetiology and Pathogenesis.

The pathogenesis of polyarteritis nodosa is unclear, but cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa has been associated with preceding infections, especially streptococcal upper respiratory infections, as well as inflammatory bowel disease [4]. There have been multiple reports of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa in children associated with streptococcal infections, including recurrent cases and even several cases associated with post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis [1,3]. Other reported triggers in children include malaria, immunizations, insect bite or drugs [5]. There have been interesting reports of newborns with cutaneous vasculitis born to mothers with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, suggesting the disease may be caused by circulating factors that cross the placenta [2,6].

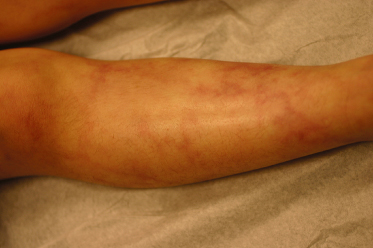

Clinical Features.

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa usually presents with livedo reticularis and/or bilateral tender erythematous nodules that may ulcerate, most commonly on the lower extremities (Fig. 77.2). Acral cyanosis or peripheral gangrene leading to autoamputation may also be seen [2,5,6]. Patients may have low-grade fevers, arthralgias or myalgias, or malaise, and may develop a peripheral neuropathy [4]. Mild haematuria may be found but serious renal involvement does not occur [4,7]. The course is often chronic or relapsing but considered to be relatively benign.

Fig. 77.2 Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. An 11-year-old boy with livedo reticularis on his lower extremities.

Histopathology.

Histopathology of polyarteritis nodosa reveals periarteritis of small- to medium-sized arteries and arterioles in the septa of the upper subcutis or at the dermal-subcutaneous junction, with a dense predominantly neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltrate. The vessel wall becomes hyalinized with narrowing or complete occlusion of the lumen. The inflammatory infiltrate may extend focally into the surrounding septum or lobule [4].

Investigations.

While patients with systemic polyarteritis nodosa may have abnormal laboratory studies such as positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA), rheumatoid factor or cryoglobulins, these are usually negative in patients with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa except for non-specific inflammatory markers such as an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. There is, however, at least one report of a child with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa and positive p-ANCA [8].

Treatment.

Treatment should be targeted at any associated infection or systemic illness, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic corticosteroids, or rarely other immunosuppressants may be used to control inflammation.

Superficial Thrombophlebitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree